No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

The Standing Rigging On A Sailboat Explained

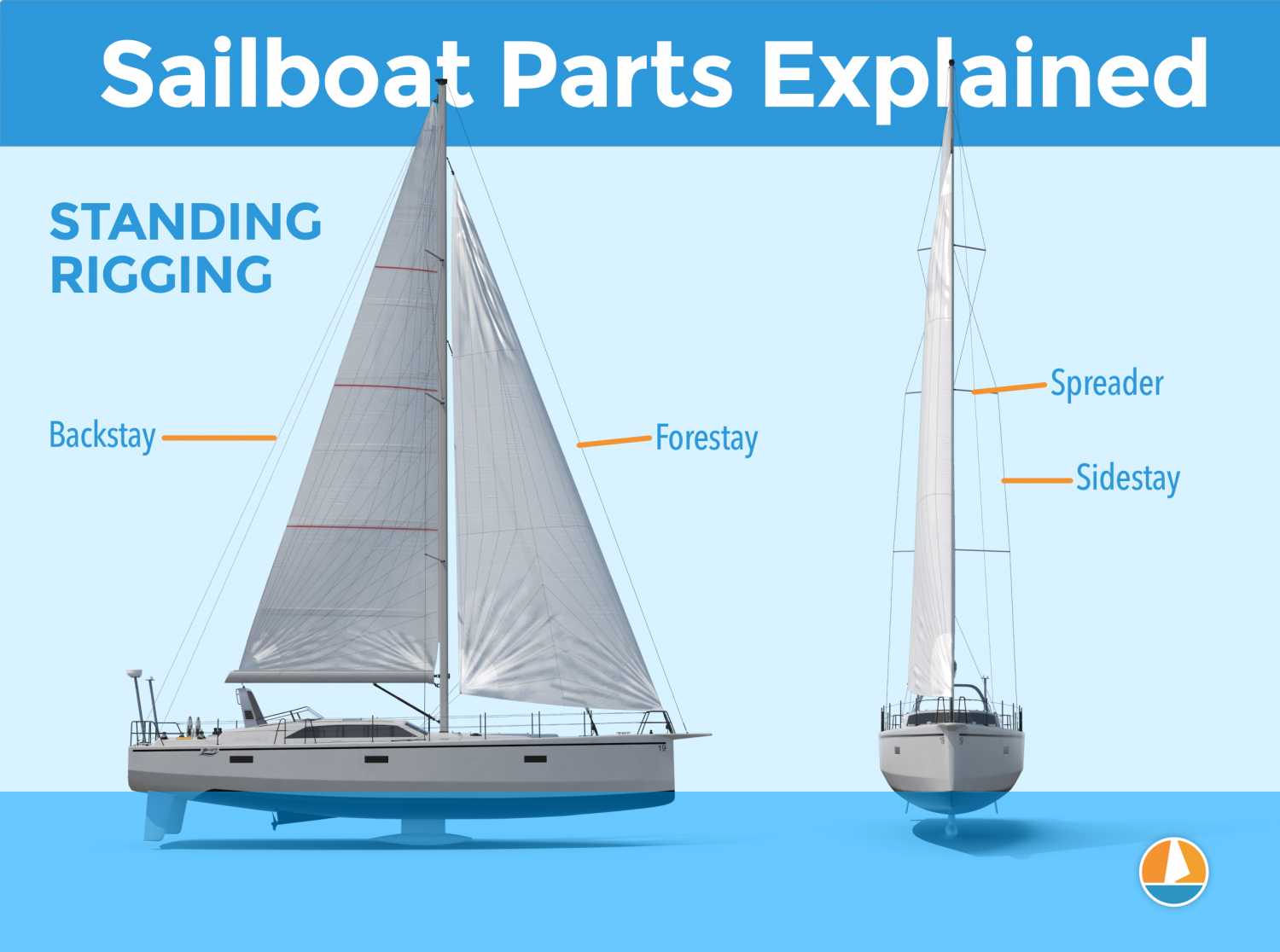

The standing rigging on a sailboat is a system of stainless steel wires that holds the mast upright and supports the spars.

In this guide, I’ll explain the basics of a sailboat’s hardware and rigging, how it works, and why it is a fundamental and vital part of the vessel. We’ll look at the different parts of the rig, where they are located, and their function.

We will also peek at a couple of different types of rigs and their variations to determine their differences. In the end, I will explain some additional terms and answer some practical questions I often get asked.

But first off, it is essential to understand what standing rigging is and its purpose on a sailboat.

The purpose of the standing rigging

Like I said in the beginning, the standing rigging on a sailboat is a system of stainless steel wires that holds the mast upright and supports the spars. When sailing, the rig helps transfer wind forces from the sails to the boat’s structure. This is critical for maintaining the stability and performance of the vessel.

The rig can also consist of other materials, such as synthetic lines or steel rods, yet its purpose is the same. But more on that later.

Since the rig supports the mast, you’ll need to ensure that it is always in appropriate condition before taking your boat out to sea. Let me give you an example from a recent experience.

Dismasting horrors

I had a company inspect the entire rig on my sailboat while preparing for an Atlantic crossing. The rigger didn’t find any issues, but I decided to replace the rig anyway because of its unknown age. I wanted to do the job myself so I could learn how it is done correctly.

Not long after, we left Gibraltar and sailed through rough weather for eight days before arriving in Las Palmas. We were safe and sound and didn’t experience any issues. Unfortunately, several other boats arriving before us had suffered rig failures. They lost their masts and sails—a sorrowful sight but also a reminder of how vital the rigging is on a sailboat.

The most common types of rigging on a sailboat

The most commonly used rig type on modern sailing boats is the fore-and-aft Bermuda Sloop rig with one mast and just one headsail. Closely follows the Cutter rig and the Ketch rig. They all have a relatively simple rigging layout. Still, there are several variations and differences in how they are set up.

A sloop has a single mast, and the Ketch has one main mast and an additional shorter mizzen mast further aft. A Cutter rig is similar to the Bermuda Sloop with an additional cutter forestay, allowing it to fly two overlapping headsails.

You can learn more about the differences and the different types of sails they use in this guide. For now, we’ll focus on the Bermuda rig.

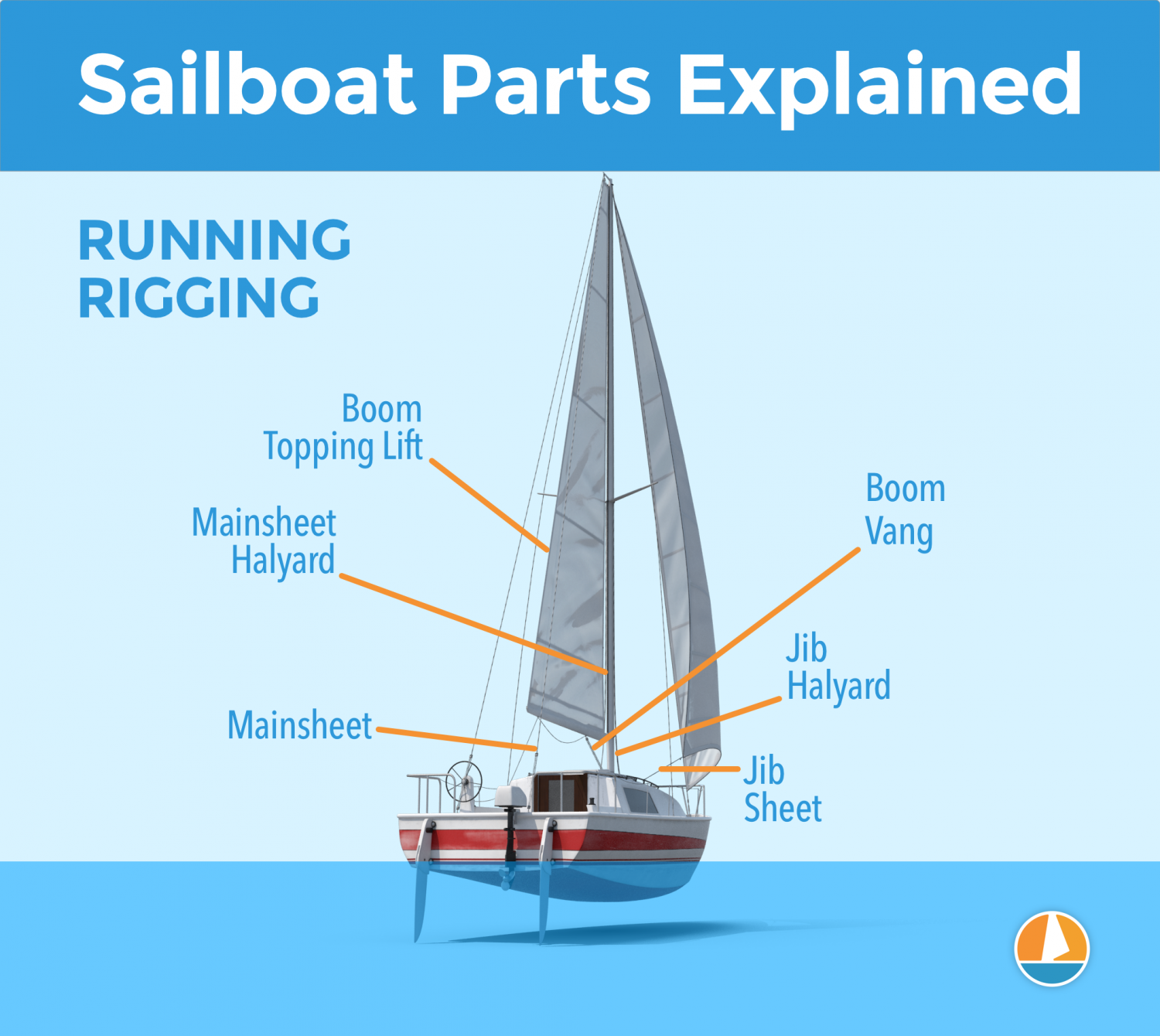

The difference between standing rigging and running rigging

Sometimes things can get confusing as some of our nautical terms are used for multiple items depending on the context. Let me clarify just briefly:

The rig or rigging on a sailboat is a common term for two parts:

- The standing rigging consists of wires supporting the mast on a sailboat and reinforcing the spars from the force of the sails when sailing.

- The running rigging consists of the halyards, sheets, and lines we use to hoist, lower, operate, and control the sails on a sailboat.

Check out my guide on running rigging here !

The difference between a fractional and a masthead rig

A Bermuda rig is split into two groups. The Masthead rig and the Fractional rig.

The Masthead rig has a forestay running from the bow to the top of the mast, and the spreaders point 90 degrees to the sides. A boat with a masthead rig typically carries a bigger overlapping headsail ( Genoa) and a smaller mainsail. Very typical on the Sloop, Ketch, and Cutter rigs.

A Fractional rig has forestays running from the bow to 1/4 – 1/8 from the top of the mast, and the spreaders are swept backward. A boat with a fractional rig also has the mast farther forward than a masthead rig, a bigger mainsail, and a smaller headsail, usually a Jib. Very typical on more performance-oriented sailboats.

There are exceptions in regards to the type of headsail, though. Many performance cruisers use a Genoa instead of a Jib , making the difference smaller.

Some people also fit an inner forestay, or a babystay, to allow flying a smaller staysail.

Explaining the parts and hardware of the standing rigging

The rigging on a sailing vessel relies on stays and shrouds in addition to many hardware parts to secure the mast properly. And we also have nautical terms for each of them. Since a system relies on every aspect of it to be in equally good condition, we want to familiarize ourselves with each part and understand its function.

Forestay and Backstay

The forestay is a wire that runs from the bow to the top of the mast. Some boats, like the Cutter rig, can have several additional inner forestays in different configurations.

The backstay is the wire that runs from the back of the boat to the top of the mast. Backstays have a tensioner, often hydraulic, to increase the tension when sailing upwind. Some rigs, like the Cutter, have running backstays and sometimes checkstays or runners, to support the rig.

The primary purpose of the forestay and backstay is to prevent the mast from moving fore and aft. The tensioner on the backstay also allows us to trim and tune the rig to get a better shape of the sails.

The shrouds are the wires or lines used on modern sailboats and yachts to support the mast from sideways motion.

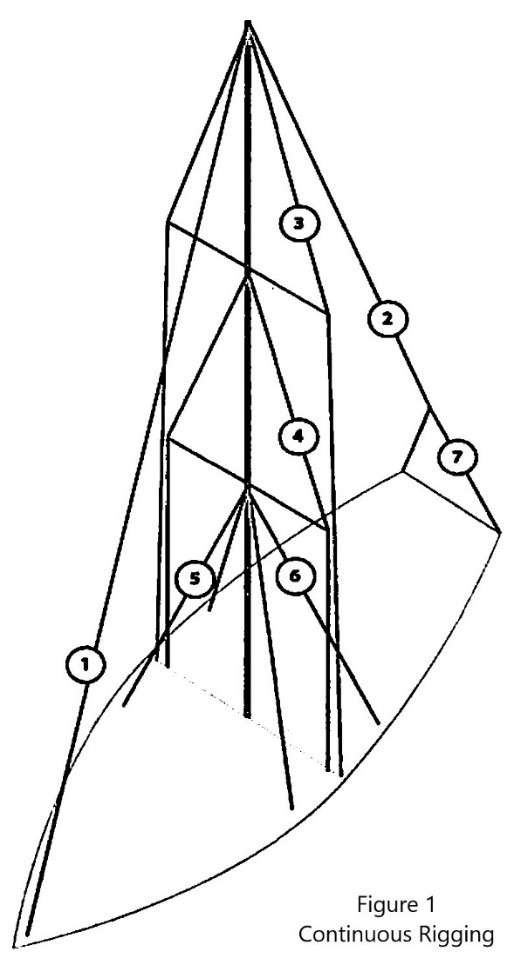

There are usually four shrouds on each side of the vessel. They are connected to the side of the mast and run down to turnbuckles attached through toggles to the chainplates bolted on the deck.

- Cap shrouds run from the top of the mast to the deck, passing through the tips of the upper spreaders.

- Intermediate shrouds run from the lower part of the mast to the deck, passing through the lower set of spreaders.

- Lower shrouds are connected to the mast under the first spreader and run down to the deck – one fore and one aft on each side of the boat.

This configuration is called continuous rigging. We won’t go into the discontinuous rigging used on bigger boats in this guide, but if you are interested, you can read more about it here .

Shroud materials

Shrouds are usually made of 1 x 19 stainless steel wire. These wires are strong and relatively easy to install but are prone to stretch and corrosion to a certain degree. Another option is using stainless steel rods.

Rod rigging

Rod rigging has a stretch coefficient lower than wire but is more expensive and can be intricate to install. Alternatively, synthetic rigging is becoming more popular as it weighs less than wire and rods.

Synthetic rigging

Fibers like Dyneema and other aramids are lightweight and provide ultra-high tensile strength. However, they are expensive and much more vulnerable to chafing and UV damage than other options. In my opinion, they are best suited for racing and regatta-oriented sailboats.

Wire rigging

I recommend sticking to the classic 316-graded stainless steel wire rigging for cruising sailboats. It is also the most reasonable of the options. If you find yourself in trouble far from home, you are more likely to find replacement wire than another complex rigging type.

Relevant terms on sailboat rigging and hardware

The spreaders are the fins or wings that space the shrouds away from the mast. Most sailboats have at least one set, but some also have two or three. Once a vessel has more than three pairs of spreaders, we are probably talking about a big sailing yacht.

A turnbuckle is the fitting that connects the shrouds to the toggle and chainplate on the deck. These are adjustable, allowing you to tension the rig.

A chainplate is a metal plate bolted to a strong point on the deck or side of the hull. It is usually reinforced with a backing plate underneath to withstand the tension from the shrouds.

The term mast head should be distinct from the term masthead rigging. Out of context, the mast head is the top of the mast.

A toggle is a hardware fitting to connect the turnbuckles on the shrouds and the chainplate.

How tight should the standing rigging be?

It is essential to periodically check the tension of the standing rigging and make adjustments to ensure it is appropriately set. If the rig is too loose, it allows the mast to sway excessively, making the boat perform poorly.

You also risk applying a snatch load during a tack or a gybe which can damage the rig. On the other hand, if the standing rigging is too tight, it can strain the rig and the hull and lead to structural failure.

The standing rigging should be tightened enough to prevent the mast from bending sideways under any point of sail. If you can move the mast by pulling the cap shrouds by hand, the rigging is too loose and should be tensioned. Once the cap shrouds are tightened, follow up with the intermediates and finish with the lower shrouds. It is critical to tension the rig evenly on both sides.

The next you want to do is to take the boat out for a trip. Ensure that the mast isn’t bending over to the leeward side when you are sailing. A little movement in the leeward shrouds is normal, but they shouldn’t swing around. If the mast bends to the leeward side under load, the windward shrouds need to be tightened. Check the shrouds while sailing on both starboard and port tack.

Once the mast is in a column at any point of sail, your rigging should be tight and ready for action.

If you feel uncomfortable adjusting your rig, get a professional rigger to inspect and reset it.

How often should the standing rigging be replaced on a sailboat?

I asked the rigger who produced my new rig for Ellidah about how long I could expect my new rig to last, and he replied with the following:

The standing rigging should be replaced after 10 – 15 years, depending on how hard and often the boat has sailed. If it is well maintained and the vessel has sailed conservatively, it will probably last more than 20 years. However, corrosion or cracked strands indicate that the rig or parts are due for replacement regardless of age.

If you plan on doing extended offshore sailing and don’t know the age of your rig, I recommend replacing it even if it looks fine. This can be done without removing the mast from the boat while it is still in the water.

How much does it cost to replace the standing rigging?

The cost of replacing the standing rigging will vary greatly depending on the size of your boat and the location you get the job done. For my 41 feet sloop, I did most of the installation myself and paid approximately $4700 for the entire rig replacement.

Can Dyneema be used for standing rigging?

Dyneema is a durable synthetic fiber that can be used for standing rigging. Its low weight, and high tensile strength makes it especially popular amongst racers. Many cruisers also carry Dyneema onboard as spare parts for failing rigging.

How long does dyneema standing rigging last?

Dyneema rigging can outlast wire rigging if it doesn’t chafe on anything sharp. There are reports of Dyneema rigging lasting as long as 15 years, but manufacturers like Colligo claim their PVC shrink-wrapped lines should last 8 to 10 years. You can read more here .

Final words

Congratulations! By now, you should have a much better understanding of standing rigging on a sailboat. We’ve covered its purpose and its importance for performance and safety. While many types of rigs and variations exist, the hardware and concepts are often similar. Now it’s time to put your newfound knowledge into practice and set sail!

Or, if you’re not ready just yet, I recommend heading over to my following guide to learn more about running rigging on a sailboat.

Sharing is caring!

Skipper, Electrician and ROV Pilot

Robin is the founder and owner of Sailing Ellidah and has been living on his sailboat since 2019. He is currently on a journey to sail around the world and is passionate about writing his story and helpful content to inspire others who share his interest in sailing.

Very well written. Common sense layout with just enough photos and sketches. I enjoyed reading this article.

Thank you for the kind words.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Beginner’s Guide: How To Rig A Sailboat – Step By Step Tutorial

Alex Morgan

Rigging a sailboat is a crucial process that ensures the proper setup and functioning of a sailboat’s various components. Understanding the process and components involved in rigging is essential for any sailor or boat enthusiast. In this article, we will provide a comprehensive guide on how to rig a sailboat.

Introduction to Rigging a Sailboat

Rigging a sailboat refers to the process of setting up the components that enable the sailboat to navigate through the water using wind power. This includes assembling and positioning various parts such as the mast, boom, standing rigging, running rigging, and sails.

Understanding the Components of a Sailboat Rigging

Before diving into the rigging process, it is important to have a good understanding of the key components involved. These components include:

The mast is the tall vertical spar that provides vertical support to the sails and holds them in place.

The boom is the horizontal spar that runs along the bottom edge of the sail and helps control the shape and position of the sail.

- Standing Rigging:

Standing rigging consists of the wires and cables that support and stabilize the mast, keeping it upright.

- Running Rigging:

Running rigging refers to the lines and ropes used to control the sails, such as halyards, sheets, and control lines.

Preparing to Rig a Sailboat

Before rigging a sailboat, there are a few important steps to take. These include:

- Checking the Weather Conditions:

It is crucial to assess the weather conditions before rigging a sailboat. Unfavorable weather, such as high winds or storms, can make rigging unsafe.

- Gathering the Necessary Tools and Equipment:

Make sure to have all the necessary tools and equipment readily available before starting the rigging process. This may include wrenches, hammers, tape, and other common tools.

- Inspecting the Rigging Components:

In the upcoming sections of this article, we will provide a step-by-step guide on how to rig a sailboat, as well as important safety considerations and tips to keep in mind. By following these guidelines, you will be able to rig your sailboat correctly and safely, allowing for a smooth and enjoyable sailing experience.

Key takeaway:

- Rigging a sailboat maximizes efficiency: Proper rigging allows for optimized sailing performance, ensuring the boat moves smoothly through the water.

- Understanding sailboat rigging components: Familiarity with the various parts of a sailboat rigging, such as the mast, boom, and standing and running riggings, is essential for effective rigging setup.

- Importance of safety in sailboat rigging: Ensuring safety is crucial during the rigging process, including wearing a personal flotation device, securing loose ends and lines, and being mindful of overhead power lines.

Get ready to set sail and dive into the fascinating world of sailboat rigging! We’ll embark on a journey to understand the various components that make up a sailboat’s rigging. From the majestic mast to the nimble boom , and the intricate standing rigging to the dynamic running rigging , we’ll explore the crucial elements that ensure smooth sailing. Not forgetting the magnificent sail, which catches the wind and propels us forward. So grab your sea legs and let’s uncover the secrets of sailboat rigging together.

Understanding the mast is crucial when rigging a sailboat. Here are the key components and steps to consider:

1. The mast supports the sails and rigging of the sailboat. It is made of aluminum or carbon fiber .

2. Before stepping the mast , ensure that the area is clear and the boat is stable. Have all necessary tools and equipment ready.

3. Inspect the mast for damage or wear. Check for corrosion , loose fittings , and cracks . Address any issues before proceeding.

4. To step the mast , carefully lift it into an upright position and insert the base into the mast step on the deck of the sailboat.

5. Secure the mast using the appropriate rigging and fasteners . Attach the standing rigging , such as shrouds and stays , to the mast and the boat’s hull .

Fact: The mast of a sailboat is designed to withstand wind resistance and the tension of the rigging for stability and safe sailing.

The boom is an essential part of sailboat rigging. It is a horizontal spar that stretches from the mast to the aft of the boat. Constructed with durable yet lightweight materials like aluminum or carbon fiber, the boom provides crucial support and has control over the shape and position of the sail. It is connected to the mast through a boom gooseneck , allowing it to pivot. One end of the boom is attached to the mainsail, while the other end is equipped with a boom vang or kicker, which manages the tension and angle of the boom. When the sail is raised, the boom is also lifted and positioned horizontally by using the topping lift or lazy jacks.

An incident serves as a warning that emphasizes the significance of properly securing the boom. In strong winds, an improperly fastened boom swung across the deck, resulting in damage to the boat and creating a safety hazard. This incident highlights the importance of correctly installing and securely fastening all rigging components, including the boom, to prevent accidents and damage.

3. Standing Rigging

When rigging a sailboat, the standing rigging plays a vital role in providing stability and support to the mast . It consists of several key components, including the mast itself, along with the shrouds , forestay , backstay , and intermediate shrouds .

The mast, a vertical pole , acts as the primary support structure for the sails and the standing rigging. Connected to the top of the mast are the shrouds , which are cables or wires that extend to the sides of the boat, providing essential lateral support .

The forestay is another vital piece of the standing rigging. It is a cable or wire that runs from the top of the mast to the bow of the boat, ensuring forward support . Similarly, the backstay , also a cable or wire, runs from the mast’s top to the stern of the boat, providing important backward support .

To further enhance the rig’s stability , intermediate shrouds are installed. These additional cables or wires are positioned between the main shrouds, as well as the forestay or backstay. They offer extra support , strengthening the standing rigging system.

Regular inspections of the standing rigging are essential to detect any signs of wear, such as fraying or corrosion . It is crucial to ensure that all connections within the rig are tight and secure, to uphold its integrity. Should any issues be identified, immediate attention must be given to prevent accidents or damage to the boat. Prioritizing safety is of utmost importance when rigging a sailboat, thereby necessitating proper maintenance of the standing rigging. This ensures a safe and enjoyable sailing experience.

Note: <p> tags have been kept intact.

4. Running Rigging

Running Rigging

When rigging a sailboat, the running rigging is essential for controlling the sails and adjusting their position. It is important to consider several aspects when dealing with the running rigging.

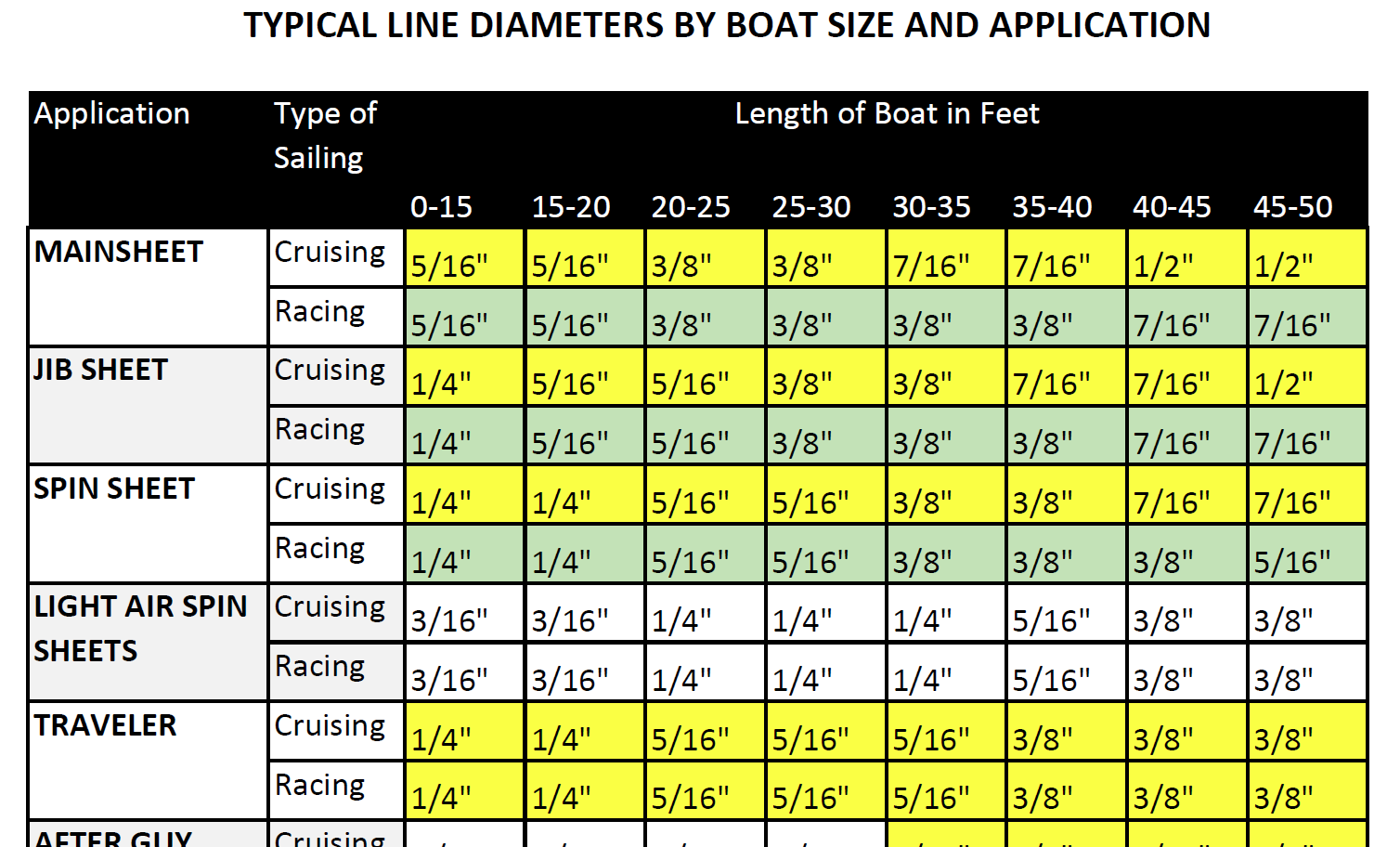

1. Choose the right rope: The running rigging typically consists of ropes with varying properties such as strength, stretch, and durability. Weather conditions and sailboat size should be considered when selecting the appropriate rope.

2. Inspect and maintain the running rigging: Regularly check for signs of wear, fraying, or damage. To ensure safety and efficiency, replace worn-out ropes.

3. Learn essential knot tying techniques: Having knowledge of knots like the bowline, cleat hitch, and reef knot is crucial for securing the running rigging and adjusting sails.

4. Understand different controls: The running rigging includes controls such as halyards, sheets, and control lines. Familiarize yourself with their functions and proper usage to effectively control sail position and tension.

5. Practice proper sail trimming: Adjusting the tension of the running rigging significantly affects sailboat performance. Mastering sail trimming techniques will help optimize sail shape and maximize speed.

By considering these factors and mastering running rigging techniques, you can enhance your sailing experience and ensure the safe operation of your sailboat.

The sail is the central component of sailboat rigging as it effectively harnesses the power of the wind to propel the boat.

When considering the sail, there are several key aspects to keep in mind:

– Material: Sails are typically constructed from durable and lightweight materials such as Dacron or polyester. These materials provide strength and resistance to various weather conditions.

– Shape: The shape of the sail plays a critical role in its overall performance. A well-shaped sail should have a smooth and aerodynamic profile, which allows for maximum efficiency in capturing wind power.

– Size: The size of the sail is determined by its sail area, which is measured in square feet or square meters. Larger sails have the ability to generate more power, but they require greater skill and experience to handle effectively.

– Reefing: Reefing is the process of reducing the sail’s size to adapt to strong winds. Sails equipped with reefing points allow sailors to decrease the sail area, providing better control in challenging weather conditions.

– Types: There are various types of sails, each specifically designed for different purposes. Common sail types include mainsails, jibs, genoas, spinnakers, and storm sails. Each type possesses its own unique characteristics and is utilized under specific wind conditions.

Understanding the sail and its characteristics is vital for sailors, as it directly influences the boat’s speed, maneuverability, and overall safety on the water.

Getting ready to rig a sailboat requires careful preparation and attention to detail. In this section, we’ll dive into the essential steps you need to take before setting sail. From checking the weather conditions to gathering the necessary tools and equipment, and inspecting the rigging components, we’ll ensure that you’re fully equipped to navigate the open waters with confidence. So, let’s get started on our journey to successfully rigging a sailboat!

1. Checking the Weather Conditions

Checking the weather conditions is crucial before rigging a sailboat for a safe and enjoyable sailing experience. Monitoring the wind speed is important in order to assess the ideal sailing conditions . By checking the wind speed forecast , you can determine if the wind is strong or light . Strong winds can make sailboat control difficult, while very light winds can result in slow progress.

Another important factor to consider is the wind direction . Assessing the wind direction is crucial for route planning and sail adjustment. Favorable wind direction helps propel the sailboat efficiently, making your sailing experience more enjoyable.

In addition to wind speed and direction, it is also important to consider weather patterns . Keep an eye out for impending storms or heavy rain. It is best to avoid sailing in severe weather conditions that may pose a safety risk. Safety should always be a top priority when venturing out on a sailboat.

Another aspect to consider is visibility . Ensure good visibility by checking for fog, haze, or any other conditions that may hinder navigation. Clear visibility is important for being aware of other boats and potential obstacles that may come your way.

Be aware of the local conditions . Take into account factors such as sea breezes, coastal influences, or tidal currents. These local factors greatly affect sailboat performance and safety. By considering all of these elements, you can have a successful and enjoyable sailing experience.

Here’s a true story to emphasize the importance of checking the weather conditions. One sunny afternoon, a group of friends decided to go sailing. Before heading out, they took the time to check the weather conditions. They noticed that the wind speed was expected to be around 10 knots, which was perfect for their sailboat. The wind direction was coming from the northwest, allowing for a pleasant upwind journey. With clear visibility and no approaching storms, they set out confidently, enjoying a smooth and exhilarating sail. This positive experience was made possible by their careful attention to checking the weather conditions beforehand.

2. Gathering the Necessary Tools and Equipment

To efficiently gather all of the necessary tools and equipment for rigging a sailboat, follow these simple steps:

- First and foremost, carefully inspect your toolbox to ensure that you have all of the basic tools such as wrenches, screwdrivers, and pliers.

- Make sure to check if you have a tape measure or ruler available as they are essential for precise measurements of ropes or cables.

- Don’t forget to include a sharp knife or rope cutter in your arsenal as they will come in handy for cutting ropes or cables to the desired lengths.

- Gather all the required rigging hardware including shackles, pulleys, cleats, and turnbuckles.

- It is always prudent to check for spare ropes or cables in case replacements are needed during the rigging process.

- If needed, consider having a sailing knife or marlinspike tool for splicing ropes or cables.

- For rigging a larger sailboat, it is crucial to have a mast crane or hoist to assist with stepping the mast.

- Ensure that you have a ladder or some other means of reaching higher parts of the sailboat, such as the top of the mast.

Once, during the preparation of rigging my sailboat, I had a moment of realization when I discovered that I had forgotten to bring a screwdriver . This unfortunate predicament occurred while I was in a remote location with no nearby stores. Being resourceful, I improvised by utilizing a multipurpose tool with a small knife blade, which served as a makeshift screwdriver. Although it was not the ideal solution, it allowed me to accomplish the task. Since that incident, I have learned the importance of double-checking my toolbox before commencing any rigging endeavor. This practice ensures that I have all of the necessary tools and equipment, preventing any unexpected surprises along the way.

3. Inspecting the Rigging Components

Inspecting the rigging components is essential for rigging a sailboat safely. Here is a step-by-step guide on inspecting the rigging components:

1. Visually inspect the mast, boom, and standing rigging for damage, such as corrosion, cracks, or loose fittings.

2. Check the tension of the standing rigging using a tension gauge. It should be within the recommended range from the manufacturer.

3. Examine the turnbuckles, clevis pins, and shackles for wear or deformation. Replace any damaged or worn-out hardware.

4. Inspect the running rigging, including halyards and sheets, for fraying, signs of wear, or weak spots. Replace any worn-out lines.

5. Check the sail for tears, wear, or missing hardware such as grommets or luff tape.

6. Pay attention to the connections between the standing rigging and the mast. Ensure secure connections without any loose or missing cotter pins or rigging screws.

7. Inspect all fittings, such as mast steps, spreader brackets, and tangs, to ensure they are securely fastened and in good condition.

8. Conduct a sea trial to assess the rigging’s performance and make necessary adjustments.

Regularly inspecting the rigging components is crucial for maintaining the sailboat’s rigging system’s integrity, ensuring safe sailing conditions, and preventing accidents or failures at sea.

Once, I went sailing on a friend’s boat without inspecting the rigging components beforehand. While at sea, a sudden gust of wind caused one of the shrouds to snap. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but we had to cut the sail loose and carefully return to the marina. This incident taught me the importance of inspecting the rigging components before sailing to avoid unforeseen dangers.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Rig a Sailboat

Get ready to set sail with our step-by-step guide on rigging a sailboat ! We’ll take you through the process from start to finish, covering everything from stepping the mast to setting up the running rigging . Learn the essential techniques and tips for each sub-section, including attaching the standing rigging and installing the boom and sails . Whether you’re a seasoned sailor or a beginner, this guide will have you ready to navigate the open waters with confidence .

1. Stepping the Mast

To step the mast of a sailboat, follow these steps:

1. Prepare the mast: Position the mast near the base of the boat.

2. Attach the base plate: Securely fasten the base plate to the designated area on the boat.

3. Insert the mast step: Lower the mast step into the base plate and align it with the holes or slots.

4. Secure the mast step: Use fastening screws or bolts to fix the mast step in place.

5. Raise the mast: Lift the mast upright with the help of one or more crew members.

6. Align the mast: Adjust the mast so that it is straight and aligned with the boat’s centerline.

7. Attach the shrouds: Connect the shrouds to the upper section of the mast, ensuring proper tension.

8. Secure the forestay: Attach the forestay to the bow of the boat, ensuring it is securely fastened.

9. Final adjustments: Check the tension of the shrouds and forestay, making any necessary rigging adjustments.

Following these steps ensures that the mast is properly stepped and securely in place, allowing for a safe and efficient rigging process. Always prioritize safety precautions and follow manufacturer guidelines for your specific sailboat model.

2. Attaching the Standing Rigging

To attach the standing rigging on a sailboat, commence by preparing the essential tools and equipment, including wire cutters, crimping tools, and turnbuckles.

Next, carefully inspect the standing rigging components for any indications of wear or damage.

After inspection, fasten the bottom ends of the shrouds and stays to the chainplates on the deck.

Then, securely affix the top ends of the shrouds and stays to the mast using adjustable turnbuckles .

To ensure proper tension, adjust the turnbuckles accordingly until the mast is upright and centered.

Utilize a tension gauge to measure the tension in the standing rigging, aiming for around 15-20% of the breaking strength of the rigging wire.

Double-check all connections and fittings to verify their security and proper tightness.

It is crucial to regularly inspect the standing rigging for any signs of wear or fatigue and make any necessary adjustments or replacements.

By diligently following these steps, you can effectively attach the standing rigging on your sailboat, ensuring its stability and safety while on the water.

3. Installing the Boom and Sails

To successfully complete the installation of the boom and sails on a sailboat, follow these steps:

1. Begin by securely attaching the boom to the mast. Slide it into the gooseneck fitting and ensure it is firmly fastened using a boom vang or another appropriate mechanism.

2. Next, attach the main sail to the boom. Slide the luff of the sail into the mast track and securely fix it in place using sail slides or cars.

3. Connect the mainsheet to the boom. One end should be attached to the boom while the other end is connected to a block or cleat on the boat.

4. Proceed to attach the jib or genoa. Make sure to securely attach the hanks or furler line to the forestay to ensure stability.

5. Connect the jib sheets. One end of each jib sheet should be attached to the clew of the jib or genoa, while the other end is connected to a block or winch on the boat.

6. Before setting sail, it is essential to thoroughly inspect all lines and connections. Ensure that they are properly tensioned and that all connections are securely fastened.

During my own experience of installing the boom and sails on my sailboat, I unexpectedly encountered a strong gust of wind. As a result, the boom began swinging uncontrollably, requiring me to quickly secure it to prevent any damage. This particular incident served as a vital reminder of the significance of properly attaching and securing the boom, as well as the importance of being prepared for unforeseen weather conditions while rigging a sailboat.

4. Setting Up the Running Rigging

Setting up the running rigging on a sailboat involves several important steps. First, attach the halyard securely to the head of the sail. Then, connect the sheets to the clew of the sail. If necessary, make sure to secure the reefing lines . Attach the outhaul line to the clew of the sail and connect the downhaul line to the tack of the sail. It is crucial to ensure that all lines are properly cleated and organized. Take a moment to double-check the tension and alignment of each line. If you are using a roller furling system, carefully wrap the line around the furling drum and securely fasten it. Perform a thorough visual inspection of the running rigging to check for any signs of wear or damage. Properly setting up the running rigging is essential for safe and efficient sailing. It allows for precise control of the sail’s position and shape, ultimately optimizing the boat’s performance on the water.

Safety Considerations and Tips

When it comes to rigging a sailboat, safety should always be our top priority. In this section, we’ll explore essential safety considerations and share some valuable tips to ensure smooth sailing. From the importance of wearing a personal flotation device to securing loose ends and lines, and being cautious around overhead power lines, we’ll equip you with the knowledge and awareness needed for a safe and enjoyable sailing experience. So, let’s set sail and dive into the world of safety on the water!

1. Always Wear a Personal Flotation Device

When rigging a sailboat, it is crucial to prioritize safety and always wear a personal flotation device ( PFD ). Follow these steps to properly use a PFD:

- Select the appropriate Coast Guard-approved PFD that fits your size and weight.

- Put on the PFD correctly by placing your arms through the armholes and securing all the straps for a snug fit .

- Adjust the PFD for comfort , ensuring it is neither too tight nor too loose, allowing freedom of movement and adequate buoyancy .

- Regularly inspect the PFD for any signs of wear or damage, such as tears or broken straps, and replace any damaged PFDs immediately .

- Always wear your PFD when on or near the water, even if you are a strong swimmer .

By always wearing a personal flotation device and following these steps, you will ensure your safety and reduce the risk of accidents while rigging a sailboat. Remember, prioritize safety when enjoying water activities.

2. Secure Loose Ends and Lines

Inspect lines and ropes for frayed or damaged areas. Secure loose ends and lines with knots or appropriate cleats or clamps. Ensure all lines are properly tensioned to prevent loosening during sailing. Double-check all connections and attachments for security. Use additional safety measures like extra knots or stopper knots to prevent line slippage.

To ensure a safe sailing experience , it is crucial to secure loose ends and lines properly . Neglecting this important step can lead to accidents or damage to the sailboat. By inspecting, securing, and tensioning lines , you can have peace of mind knowing that everything is in place. Replace or repair any compromised lines or ropes promptly. Securing loose ends and lines allows for worry-free sailing trips .

3. Be Mindful of Overhead Power Lines

When rigging a sailboat, it is crucial to be mindful of overhead power lines for safety. It is important to survey the area for power lines before rigging the sailboat. Maintain a safe distance of at least 10 feet from power lines. It is crucial to avoid hoisting tall masts or long antenna systems near power lines to prevent contact. Lower the mast and tall structures when passing under a power line to minimize the risk of contact. It is also essential to be cautious in areas where power lines run over the water and steer clear to prevent accidents.

A true story emphasizes the importance of being mindful of overhead power lines. In this case, a group of sailors disregarded safety precautions and their sailboat’s mast made contact with a low-hanging power line, resulting in a dangerous electrical shock. Fortunately, no serious injuries occurred, but it serves as a stark reminder of the need to be aware of power lines while rigging a sailboat.

Some Facts About How To Rig A Sailboat:

- ✅ Small sailboat rigging projects can improve sailing performance and save money. (Source: stingysailor.com)

- ✅ Rigging guides are available for small sailboats, providing instructions and tips for rigging. (Source: westcoastsailing.net)

- ✅ Running rigging includes lines used to control and trim the sails, such as halyards and sheets. (Source: sailingellidah.com)

- ✅ Hardware used in sailboat rigging includes winches, blocks, and furling systems. (Source: sailingellidah.com)

- ✅ A step-by-step guide can help beginners rig a small sailboat for sailing. (Source: tripsavvy.com)

Frequently Asked Questions

1. how do i rig a small sailboat.

To rig a small sailboat, follow these steps: – Install or check the rudder, ensuring it is firmly attached. – Attach or check the tiller, the long steering arm mounted to the rudder. – Attach the jib halyard by connecting the halyard shackle to the head of the sail and the grommet in the tack to the bottom of the forestay. – Hank on the jib by attaching the hanks of the sail to the forestay one at a time. – Run the jib sheets by tying or shackling them to the clew of the sail and running them back to the cockpit. – Attach the mainsail by spreading it out and attaching the halyard shackle to the head of the sail. – Secure the tack, clew, and foot of the mainsail to the boom using various lines and mechanisms. – Insert the mainsail slugs into the mast groove, gradually raising the mainsail as the slugs are inserted. – Cleat the main halyard and lower the centerboard into the water. – Raise the jib by pulling down on the jib halyard and cleating it on the other side of the mast. – Tighten the mainsheet and one jibsheet to adjust the sails and start moving forward.

2. What are the different types of sailboat rigs?

Sailboat rigs can be classified into three main types: – Sloop rig: This rig has a single mast with a mainsail and a headsail, typically a jib or genoa. – Cutter rig: This rig has two headsails, a smaller jib or staysail closer to the mast, and a larger headsail, usually a genoa, forward of it, alongside a mainsail. – Ketch rig: This rig has two masts, with the main mast taller than the mizzen mast. It usually has a mainsail, headsail, and a mizzen sail. Each rig has distinct characteristics and is suitable for different sailing conditions and preferences.

3. What are the essential parts of a sailboat?

The essential parts of a sailboat include: – Mast: The tall vertical spar that supports the sails. – Boom: The horizontal spar connected to the mast, which extends outward and supports the foot of the mainsail. – Rudder: The underwater appendage that steers the boat. – Centerboard or keel: A retractable or fixed fin-like structure that provides stability and prevents sideways drift. – Sails: The fabric structures that capture the wind’s energy to propel the boat. – Running rigging: The lines or ropes used to control the sails and sailing equipment. – Standing rigging: The wires and cables that support the mast and reinforce the spars. These are the basic components necessary for the functioning of a sailboat.

4. What is a spinnaker halyard?

A spinnaker halyard is a line used to hoist and control a spinnaker sail. The spinnaker is a large, lightweight sail that is used for downwind sailing or reaching in moderate to strong winds. The halyard attaches to the head of the spinnaker and is used to raise it to the top of the mast. Once hoisted, the spinnaker halyard can be adjusted to control the tension and shape of the sail.

5. Why is it important to maintain and replace worn running rigging?

It is important to maintain and replace worn running rigging for several reasons: – Safety: Worn or damaged rigging can compromise the integrity and stability of the boat, posing a safety risk to both crew and vessel. – Performance: Worn rigging can affect the efficiency and performance of the sails, diminishing the boat’s speed and maneuverability. – Reliability: Aging or worn rigging is more prone to failure, which can lead to unexpected problems and breakdowns. Regular inspection and replacement of worn running rigging is essential to ensure the safe and efficient operation of a sailboat.

6. Where can I find sailboat rigging books or guides?

There are several sources where you can find sailboat rigging books or guides: – Online: Websites such as West Coast Sailing and Stingy Sailor offer downloadable rigging guides for different sailboat models. – Bookstores: Many bookstores carry a wide selection of boating and sailing books, including those specifically focused on sailboat rigging. – Sailing schools and clubs: Local sailing schools or yacht clubs often have resources available for learning about sailboat rigging. – Manufacturers: Some sailboat manufacturers, like Hobie Cat and RS Sailing, provide rigging guides for their specific sailboat models. Consulting these resources can provide valuable information and instructions for rigging your sailboat properly.

About the author

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Latest posts

The history of sailing – from ancient times to modern adventures

History of Sailing Sailing is a time-honored tradition that has evolved over millennia, from its humble beginnings as a means of transportation to a beloved modern-day recreational activity. The history of sailing is a fascinating journey that spans cultures and centuries, rich in innovation and adventure. In this article, we’ll explore the remarkable evolution of…

Sailing Solo: Adventures and Challenges of Single-Handed Sailing

Solo Sailing Sailing has always been a pursuit of freedom, adventure, and self-discovery. While sailing with a crew is a fantastic experience, there’s a unique allure to sailing solo – just you, the wind, and the open sea. Single-handed sailing, as it’s often called, is a journey of self-reliance, resilience, and the ultimate test of…

Sustainable Sailing: Eco-Friendly Practices on the boat

Eco Friendly Sailing Sailing is an exhilarating and timeless way to explore the beauty of the open water, but it’s important to remember that our oceans and environment need our protection. Sustainable sailing, which involves eco-friendly practices and mindful decision-making, allows sailors to enjoy their adventures while minimizing their impact on the environment. In this…

Running Rigging on a Sailboat: Essential Components and Maintenance Tips

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 8, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer running rigging on a sailboat:

Running rigging refers to the ropes and lines used for controlling the sails and other movable parts on a sailboat. It includes halyards, sheets, braces, and control lines. Properly rigged running rigging is essential for efficient sail handling and maneuvering of the boat.

Understanding Running Rigging on a Sailboat: How to Get Started

Title: Deciphering the Intricacies of Running Rigging on a Sailboat: An Enlightened Journey Begins!

Introduction: Ah, the allure of sailing! Picture yourself gracefully gliding across sun-kissed waters, propelled solely by the power of the wind . If you’re new to this mesmerizing world, it’s crucial to understand every aspect – including running rigging. Fear not, fellow adventurer! This comprehensive guide will unravel the mysteries surrounding running rigging and equip you with valuable knowledge to embark upon your own nautical odyssey.

1. The Foundations: What is Running Rigging? Running rigging encompasses all the ropes and lines aboard a sailboat that are used to control sails and their systems. Think of it as a symphony conductor guiding each instrument precisely when they are needed. Understanding its components requires delving into various key elements.

2. The Halyards: Hoisting Your Sails with Elegance Halyards form an integral part of running rigging by facilitating the raising and lowering of sails effortlessly. These vital maneuvering aids connect from the masthead down to specific positions where they secure each sail precisely at one end while granting sailors control at their opposite extremity.

3. Sheets & Controls: Directing Your Power Source Next up in our deconstruction are sheets and controls – essential components for controlling sails’ angles based on wind direction. By cunningly pulling or easing these lines, you can swiftly adjust your sails’ positioning according to weather shifts, resulting in optimal performance .

4. Cleats & Winches: From Taming Lines to Seizing Moments Even Hercules would yield to cleats and winches when taming robust ropes! Cleats serve as steadfast anchors onto which lines can be temporarily secured, providing necessary stability during navigation’s turbulent moments. Winches, on the other hand, offer mechanical assistance by efficiently winding or unwinding lines using a drum mechanism – a sailor’s secret weapon for effortlessly controlling lines under high tension.

5. Blocks & Pulleys: The Silent Workhorses Up Above Blocks and pulleys, hidden amongst the chaos of running rigging, serve as silent heroes deserving recognition. These nifty devices allow lines to redirect their path efficiently, minimizing friction while maximizing mechanical advantage. Imagine them as your trusty allies, ensuring smooth adjustments without burdening you with unnecessary strain.

6. Mainsail Furling Systems: Embracing Elegance in Simplicity To master running rigging effectively, one must grasp the concept of mainsail furling systems. These mechanisms enable swift and straightforward reefing or unfurling of the mainsail using dedicated ropes or electrically-powered systems. By harnessing this technology correctly, you’ll unlock newfound ease in sailing endeavors.

Conclusion: Congratulations! You’ve delved into the intricate world of running rigging on a sailboat and emerged more enlightened than ever before. As you embark upon your maritime journey armed with this invaluable knowledge, remember that practice leads to mastery. Understanding how these distinct elements harmonize will transform you into a maestro, skillfully orchestrating every aspect of your sailing adventure with grace and finesse. Bon voyage!

A Step-by-Step Guide to Setting Up Running Rigging on a Sailboat

Title: Sailing with Confidence: A Masterclass on Setting Up Running Rigging

Introduction:

Embarking on the open sea , feeling the wind against your face as you glide through the water, there’s no greater thrill than sailing. However, to truly harness the power of the wind and have a seamless experience, it is essential to understand how to set up your running rigging. In this comprehensive guide, we will take you through each step of this crucial process, equipping you with the knowledge and confidence necessary for smooth sailing adventures.

1. Assessing Your Needs: The Foundation for Success

Before diving into the nitty-gritty details of setting up your running rigging, it’s important to assess your specific needs according to your sailboat’s design and intended use. Factors such as boat size, mast height, and sail types play a significant role in determining which rigging configurations will work best for you.

2. Selecting Materials: Optimal Performance, Durability & Safety

Choosing suitable materials for running rigging is paramount to ensure reliable performance while maintaining the safety of both crew and vessel. From strong yet lightweight synthetic fibers like Dyneema or Spectra to traditional options such as polyester or nylon, understanding their properties and appropriate applications is essential in making informed decisions.

3. Understanding Key Terminology: Speaking Sailors’ Language

Like any specialized field, sailing has its own set of terminology that can feel overwhelming at first. Fear not! We’ll guide you through key terms such as halyards (hoisting lines), sheets (lines controlling sails), reefing lines (to reduce sail area), allowing you to converse confidently with fellow sailors.

4. Anchoring Your Mast: Secure Your Foundation

The process begins by firmly anchoring your mast at its base using a fitting called a mast step or deck collar. This immovable foundation provides stability throughout various sailing conditions while reducing unnecessary strain on all related rigging components .

5. Hoisting the Sails: Halyards & Their Art

To set sail, a crucial step involves hoisting your sails with precision. Correctly attaching halyards to the designated points on the mast and sail, while ensuring proper tension and alignment, will enable you to control raising, lowering, and reefing the sails with ease—an art form in itself.

6. Harnessing the Wind’s Power: Sheets & Trimming

Once your sails are aloft, skillful manipulation of sheets becomes paramount. Understanding how to trim them properly allows you to harness the wind’s power effectively while achieving maximum speed and maneuverability—a true dance between sailor and nature.

7. Streamlining Movement: Fairleads & Blocks

Efficiency is key when it comes to running rigging. By employing fairleads (pulleys) strategically placed around your vessel and appropriately using blocks (pulley combinations), you can minimize friction within your system, allowing for fluid movement with less effort during sail adjustments.

8. Reducing Sail Area: Reefing Lines at the Ready

As conditions change or storms approach, being able to reduce sail area swiftly is essential for safety purposes. Learning how to utilize reefing lines effectively enables you to adapt your sails according to environmental demands without sacrificing control or stability.

9. Fine-Tuning Your Set-Up: Tension & Balance

The final touch lies in adjusting tension throughout your running rigging system to achieve optimal balance and performance. Maintaining proper tension prevents undesirable effects like excessive wrinkles on sails or slack lines that compromise efficiency—fine-tuning that separates amateurs from seasoned sailors.

10. Everyday Maintenance: Caring For Your Rigging

Just as a well-maintained engine ensures peak performance, regularly caring for your running rigging also guarantees smooth operation over time. Simple tasks such as rinsing off saltwater residue or inspecting for wear and tear go a long way in prolonging the life of your rigging and ensuring a safe voyage.

Conclusion:

With this step-by-step guide, you are now equipped with the knowledge needed to set up running rigging on your sailboat like a seasoned sailor. By understanding the essential components, choosing suitable materials, and mastering the techniques necessary for trimming and maintenance, you’ll confidently navigate the open seas while experiencing the true joy of sailing . Bon voyage!

Frequently Asked Questions about Running Rigging on a Sailboat Demystified

Welcome to the world of sailing! If you’re a beginner or even if you’ve been sailing for a while, running rigging can often seem like a complex and confusing topic. But fear not! In this blog post, we are here to demystify all your frequently asked questions about running rigging on a sailboat.

Q: What is running rigging? A: Running rigging refers to all the lines and ropes that control and adjust the sails on a sailboat. It includes halyards, sheets, reefing lines, downhauls, and any other line used to set or trim sails .

Q: Why is running rigging important? A: Running rigging plays a crucial role in controlling the shape and position of the sails, allowing the boat to harness wind power efficiently . Properly adjusted running rigging enables better sail control, improved performance, and increased safety on board.

Q: How many types of running rigging are there? A: There are several types of running rigging found on most sailboats. Some common ones are halyards (used to lift or lower the sails), sheets (used to control the tension and angle of the sails), outhauls (used to adjust the foot of the mainsail), furling lines (used for rolling up or unfurling headsails), and vang systems (used for controlling boom height).

Q: What materials are used in running rigging? A: Traditionally, natural fibers like hemp or manila were used for ropes. However, modern sailboats mostly use synthetic fibers such as polyester or Dyneema due to their durability, low stretching properties, and resistance to UV degradation.

Q: How do I choose the right running rigging for my boat? A: The choice of running rigging depends on various factors such as boat size/type, sailing conditions, intended use, personal preference, and budget. It’s always advisable to consult with a reputable rigging professional who can assess your specific requirements and recommend the appropriate type and diameter of ropes for your boat .

Q: How often should I replace my running rigging? A: The lifespan of running rigging depends on various factors including usage, exposure to sunlight, and regular maintenance. As a general rule of thumb, inspect your running rigging regularly for signs of wear and tear. If you notice any fraying, excessive stretching, or damage, it’s essential to replace the affected lines promptly.

Q: Can I maintain my own running rigging? A: Yes! Regular maintenance is key to prolonging the life of your running rigging. Simple tasks like washing with fresh water after use, removing dirt or salt residue, and storing the lines properly can significantly extend their lifespan. However, if you’re unsure about any specific maintenance tasks or need assistance with more complex issues, it’s best to seek advice from a professional rigger.

Q: Are there any advanced techniques related to running rigging? A: Absolutely! Advanced sailing techniques often involve various adjustments using different lines simultaneously. For example, using barberhaulers to control genoa sheeting angles or implementing cunningham systems for mainsail shape adjustments. These techniques require practice and knowledge but can greatly enhance sail efficiency and boat performance.

Now that we’ve demystified some frequently asked questions about running rigging on a sailboat, we hope you feel more confident in understanding this vital aspect of sailing. Remember that every boat is unique, so investing time in learning about and maintaining your specific running rigging system will undoubtedly pay off in smoother sailing experiences ahead!

Choosing the Right Materials for Your Sailboat’s Running Rigging

When it comes to your sailboat’s running rigging, choosing the right materials can make all the difference in ensuring optimal performance and longevity. But with a plethora of options available, it can be a daunting task. Fear not, for we are here to guide you through this decision-making process, providing you with a detailed professional, witty and clever explanation.

First and foremost, let’s clarify what we mean by “running rigging.” In sailing terms, this refers to all the lines (ropes) used to control the sails and their adjustments while underway. These lines include halyards (used for raising and lowering the sails), sheets (controls the angle and trim of the sails), and various other control lines like reefing lines or vang lines. Each requires specific characteristics based on its purpose.

When considering materials for running rigging, durability is paramount. You want something that can withstand constant exposure to UV rays, saltwater, friction wear, and general wear and tear. One material that stands out in terms of resilience is Dyneema®. This high-performance synthetic fiber boasts an incredible strength-to-weight ratio similar to steel but without the weight or corrosion concerns. Paired with excellent resistance to UV degradation and abrasion resistance properties, Dyneema® offers a long-lasting solution for your running rigging needs.

But hold on! While Dyneema® may seem like an obvious choice, there are other factors to consider as well. For instance, ease of handling plays a significant role in determining which material is right for you. Some sailors prefer traditional materials like polyester or nylon due to their familiar feel and ease of tying knots. However, these materials tend to stretch more under load compared to Dyneema®, which can affect sail shape and overall performance .

To address this issue without compromising on durability or ease of handling completely, manufacturers have developed hybrid rope constructions where different fibers are combined strategically within a single line. For example, a Dyneema® core can be paired with a polyester or Technora cover, harnessing the best of both worlds. This combination provides the strength and low stretch characteristics of Dyneema® while maintaining that traditional feel when handling.

Now, let’s sprinkle in some wit and cleverness as we delve into the importance of reliability. When out on the open seas, you don’t want to be caught off guard by a line failure because you chose an unreliable material. Imagine your excitement as the wind picks up, preparing for an exhilarating sail, only to have your sailing dreams dashed due to a snapped halyard! Trust me; it’s not an experience you’ll find amusing, nor will your crew appreciate your comedic skills at such moments. So, don’t skimp on quality.

To ensure reliability and avoid any unplanned comedy acts on board, investing in well-respected brands known for their commitment to excellence is key. Reputable manufacturers like New England Ropes or Marlow Ropes are popular choices among sailors worldwide. Their rigorous testing processes and innovative designs guarantee performance reliability no matter what Mother Nature throws your way.

We hope this detailed professional, witty and clever explanation has shed some light on choosing the right materials for your sailboat’s running rigging. Remember to consider durability, ease of handling, and reliability when making your decision. And if you’re still unsure or need further assistance—don’t hesitate to reach out to fellow sailors or consult with professionals who can offer personalized advice tailored to your unique sailing style. Happy rigging!

Essential Tips for Properly Maintaining and Inspecting Running Rigging on a Sailboat

As any experienced sailor knows, properly maintaining and inspecting the running rigging on a sailboat is crucial for optimal performance and safety on the water. The running rigging refers to all the lines or ropes that control the sails, such as halyards, sheets, and control lines. Neglecting this essential aspect of sailboat ownership can lead to inefficiencies in sailing, potential equipment failures, or even dangerous situations while out at sea. So, whether you’re a seasoned sailor or just starting out, here are some essential tips to keep your running rigging in top shape.

1. Regular Inspection: The first step in proper maintenance is conducting regular inspections of your running rigging. Look for signs of wear and tear such as fraying, chafing, or any weakening spots in the ropes. Pay close attention to areas where lines are frequently under tension or make contact with other hardware, as these are typically high-stress areas prone to damage.

2. Cleaning: It’s vital to keep your running rigging clean and free from contaminants like dirt, saltwater residue, or mildew buildup that can affect their performance over time. Use a mild soap and water solution along with a soft brush to scrub away any grime.

3. Protect from UV Damage: Exposure to sunlight can accelerate the wear and degradation of your ropes due to UV radiation. Consider covering them with protective sleeves or using UV-resistant coatings specifically designed for sailing applications.

4. Lubrication: Keeping your running rigging well-lubricated ensures smooth operation and prolongs their lifespan. Apply a suitable marine-grade lubricant to reduce friction between moving parts like pulleys and cleats but be cautious not to apply excessive amounts that could attract dirt or create messy situations.

5. Check Fittings & Hardware: A comprehensive inspection should include examining all fittings and hardware associated with your running rigging – blocks, shackles, cam cleats – to ensure they are in proper working order. Tighten any loose fittings and replace any worn or damaged hardware promptly.

6. Replace Worn-out Lines: As with anything made of rope, running rigging will eventually reach the end of its serviceable life. Don’t wait for lines to fail before replacing them. Look out for signs like significant diameter reduction, loss of flexibility, or extensive wear and tear. Replacing worn-out lines early can save you from potential accidents or interruptions during your sailing adventures .

7. Proper Storage: When not in use, it’s essential to store your running rigging properly to avoid unnecessary damage or deterioration. Coil the lines neatly and hang them in a cool, dry place where they are protected from direct sunlight and extreme temperatures.

By following these essential tips for maintaining and inspecting your sailboat’s running rigging, you’ll be able to enjoy smooth sailing while ensuring your safety out on the water. Regular inspections, cleaning, UV protection, lubrication, checking fittings and hardware, timely replacements when necessary, and proper storage – all these factors contribute to keeping your running rigging in top shape for optimal performance on every voyage.

Remember that sailboat ownership is an ongoing learning process – stay curious and educate yourself further through reputable sources such as books or online forums dedicated to sailing techniques and equipment maintenance. Happy sailing!

Upgrading Your Sailboat’s Running Rigging: What You Need to Know

When it comes to sailing, few things are as important as the running rigging of your sailboat. From controlling your sails to maneuvering through tricky waters, the quality and functionality of your running rigging can make all the difference in your sailing experience. In this blog post, we will explore everything you need to know about upgrading your sailboat’s running rigging.

Why Upgrade?

Before diving into the details of upgrading your running rigging, let’s discuss why it is necessary in the first place. Over time, the wear and tear on a sailboat’s running rigging can lead to compromised performance and safety concerns. As such, periodic upgrades become essential to ensure optimal functionality and reliability on the water .

Choosing Material

One of the most critical decisions when upgrading your running rigging is choosing the right material. Traditionally, sailboats have used materials like polyester or Dacron for their ropes. While these options are cost-effective and suitable for casual sailors, advanced materials like Dyneema or Spectra offer superior strength-to-weight ratio and lower stretch capabilities.

Furthermore, these modern fibers provide exceptional durability against UV degradation and abrasion resistance – perfect for longer ocean passages or demanding racing environments. Investing in high-quality lines may be more expensive upfront but pays off by enhancing both safety and performance while extending the overall lifespan of your rigging system.

Understanding Line Construction

Now that we’ve covered material options let’s move onto line construction. When choosing new lines for your running rigging upgrade, understanding their construction plays a vital role in achieving desired results.

Double braid construction is one popular option known for its balance between stretch resistance and knotability. It consists of a core surrounded by a braided outer cover – providing both strength and flexibility when handling heavier loads.

Alternatively, single braid construction offers improved flexibility by using only one continuous rope with a braided or twisted cover. This design is perfect for smaller sailboats, giving you lighter and more manageable lines while sacrificing some load-bearing capacity.

Finding the Perfect Fit

Upgrading your running rigging goes beyond simply replacing old lines with new ones; finding the perfect fit for your specific needs is crucial. Before making any purchases, take time to assess how you use your sailboat and what characteristics matter most to you.

Consider factors like line diameter, breaking strength, elongation under load, and grip comfort when evaluating potential options. While durability is essential, striking the right balance between strength and weight can significantly enhance your sailing experience .

Installation 101

Now that you’ve selected the ideal running rigging components let’s talk about installation. Proper installation ensures optimal functionality and reduces potential snags or accidents on the water.

Start by studying your sailboat’s existing rigging setup and create a detailed plan to avoid confusion during installation. If possible, consult with experts or refer to manufacturer guidelines for best practices.

Lastly, pay careful attention to tensioning techniques when installing your new lines – correct tension prevents slack that may hinder overall performance during navigation.

Maintaining Your Upgrade

Once completed, maintaining your newly upgraded running rigging becomes an essential part of owning a sailboat. Regular inspection of ropes for wear and tear is necessary since even high-quality materials require upkeep.

Additionally, proper storage away from UV rays and harsh weather conditions can further extend the life of your upgraded running rigging. By following maintenance guidelines provided by manufacturers and incorporating routine checks in pre-sail preparations, you can ensure continued reliability throughout every journey.

Upgrading your sailboat’s running rigging is a worthwhile investment that guarantees enhanced safety and performance while providing endless possibilities on the water. Choosing suitable materials based on usage patterns, understanding line construction principles, finding the perfect fit for specific needs, meticulous installation processes, and regular maintenance are key elements in achieving desired results.

So, take the plunge and upgrade your running rigging today – it’s time to elevate your sailing experience to new heights!

Recent Posts

- Sailboat Gear and Equipment

- Sailboat Lifestyle

- Sailboat Maintenance

- Sailboat Racing

- Sailboat Tips and Tricks

- Sailboat Types

- Sailing Adventures

- Sailing Destinations

- Sailing Safety

- Sailing Techniques

Better Sailing

What is Sailboat Rigging?

The domain of rigging is an essential matter for the safety and good performance of your sailboat. Nowadays, the type of rigging is still evolving. Generally, rigging is depending on the type of sail used or the number of masts. As a basic rule, the replacement of the standing rig should be done every 10 years, except for multihulls or regattas, and rod or composite fiber rigging. A good set of rigging is of great importance in order to ensure navigation without causing any damage. A useful tip is to perform often thorough checks of the state of the rigging of your sailboat. Like this, you will prevent any possible damages from happening. So, let’s examine what exactly is sailboat rigging.

Standing and Running Rigging

Standing rigging supports your sailboat’s mast. The standing rigging consists of all the stainless steel wires that are used to support the mast. Moreover, standing rigging includes the rods, wires, and fixed lines that support the masts or bowsprit on a sailing vessel. In addition, all these reinforce the spars against wind loads transferred from the sails. On the other hand, running rigging is the rigging for controlling and shaping the sails on a sailboat. Running rigging consists of the main and jib sheet, the boom vang, the downhaul, and the jib halyard.

The subdivision of running rigging concerns the jeers, lifts, and halyards (halyards). This supporting equipment raises or lowers the sails and also controls the lower corners of the sails, i.e. the tacks and sheets. Over the centuries and up until nowadays, the history of sailboats rigging is still developing. What we’ve learned by now is that the combination of square and fore-and-aft sails in a full-rigged ship creates a highly complex, and mutually reliant set of components.

Wire Rigging

Wire rigging is the most common form of standing rigging on sailboats today. Furthermore, the style of the wire used is made of stainless steel, which is also a common wire style. What is advantageous with wire is that it’s quite affordable, especially when using swage fittings. The wire has also a long life expectancy, about 10 to 20 years, depending on use and the region you’re sailing to. However, wire rigging is more elastic than rod and synthetic rigging, thus it offers the lowest performance.

Rod Rigging

The rod rigging composition is of high-quality materials that provide low stretching. Moreover, it has a very long lifespan and great breaking strength, much more than that of its wire counterpart. Its life expectancy is attributed to the design, which is a mono strand, as well as to its composition that makes it very corrosion resistant.

Synthetic Rigging

Synthetic rigging is a new type of rigging and just like a rod, has minimum breaking strength. Nowadays, synthetic rigging offers low stretch performance features (that may vary depending on construction type), which are quite good for sailboats, among others. However, synthetic rigging will not last as long as the metal components. Most of the time, metal wire and rod are far better than synthetic rigging.

Based on the two rig types which are square-rigged and fore-and-aft, let’s divide the fore-and-aft rigs into three groups:

- Lateen Rig has a three-sided mainsail on a long yard.

- Bermuda rig which has a three-sided mainsail.

- Gaff rig is the head of the mainsail and has a four-sided mainsail.

Parts of a Sailboat Rigging and Terminology

Cruising sailboats will usually have their mast supported by 1 x 19 stainless steel wire. However, there are some racing sailboats that may choose rod rigging. Why? That’s because rod rigging has a stretch coefficient that is some 20% less than wire. The downside is that it’s more difficult to install and adjust, as well as less flexible with a shorter life span. So, let’s move on and see the parts of the sailboat’s rigging and their terminology:

- Forestay and Backstay : Forestay and backstay support the mast fore and aft. The forestay keeps the mast from falling backward. It attaches at the top of the mast. The backstay is important for the sail’s control because it directly affects the headsail and mainsail.

- Cap Shrouds and Lower Shrouds : These parts hold the mast steady athwartship. The shrouds are attached to the masthead and via chainplates to the hull. Moreover, forward and aft lower shrouds provide further support. The lower shrouds are always connected to the mast, just under the first spreader, and at the other end to the hull.

- Spreaders : In general, spreaders keep the shrouds away from the mast. What is of high importance, in terms of stability, is their length and fore-and-aft angle. The rigs of cruising boats may have up to three pairs of spreaders, depending on a number of factors such as the sailboat’s size and type. Keep in mind that the more spreaders a sailboat has then the lighter the mast section can be. Last but not least, the spreaders must be robust in order to withstand the compression loads of the shrouds.

- Masts and Booms : Masts are tall spars that carry the sails, navigate the sailboat, and control its position. Sailboat booms are horizontal spars to which the foot of a sail is bent. The booms attach to the lower part of the mast. There are some sailboats with unstayed masts, like the junk rig and catboat rigs. They have no standing rigging at all, and neither stays to support them. For example, a Bermuda rig has a single mast and just one headsail, thus a relatively simple rigging layout. On the other hand, schooners or ketches have a really complex rigging, i.e. with multi-spreader rigs. Apparently, the mast on a sailboat is an important component.

- Chainplates, Toggles, and Turnbuckles : These important components of sailboat rigging attach the shrouds to the hull. The chainplate is a metal plate that fastens to a strong point in the hull. Toggles are comprised of stainless steel fittings that absorb non-linear loads, located between the shrouds and the chainplate. Turnbuckles (or rigging screws) are also stainless steel materials that allow the shroud tension to adjust better.

- Parts of Running Rigging : As mentioned above, running rigging has to do about shaping, supporting, and stabilizing the sails on a sailing boat. Therefore, the necessary materials for running rigging are numerous and need further explanation. Some of these materials are: The topping lifts, the halyards, the outhauls and downhauls, the boom vangs, the sheets, and more.

Sailboat Rigging – Summary

So, what is sailboat rigging? Sailboat rigging concerns the wires, lines, and ropes that hold the rig and control the sails. To be more accurate, this means the tensioned stays and shrouds that support the mast. Rigging has to do about the booms, masts, yards, sails, stays, and cordage. Same way with cars, sailboats also have an engine, but in the form of sails. This is the standing and running rigging. When we refer to standing rigging this means that the stays and shrouds are supported by the mast. On the other hand, running rigging refers to rope halyards, sheets, and other control lines. Depending on the type of your sailboat, this sail-engine might be old, new, or maybe somewhere in between.

Peter is the editor of Better Sailing. He has sailed for countless hours and has maintained his own boats and sailboats for years. After years of trial and error, he decided to start this website to share the knowledge.

Related Posts

Sailing with Friends: Tie Knots, Navigate the Seas and Create Unforgettable Memories

Atlantic vs Pacific: Which is More Dangerous for Sailing?

Lagoon Catamaran Review: Are Lagoon Catamarans Good?

Best Inboard Boat Engine Brands

- Buyer's Guide

- Destinations

- Maintenance

- Sailing Info

Hit enter to search or ESC to close.

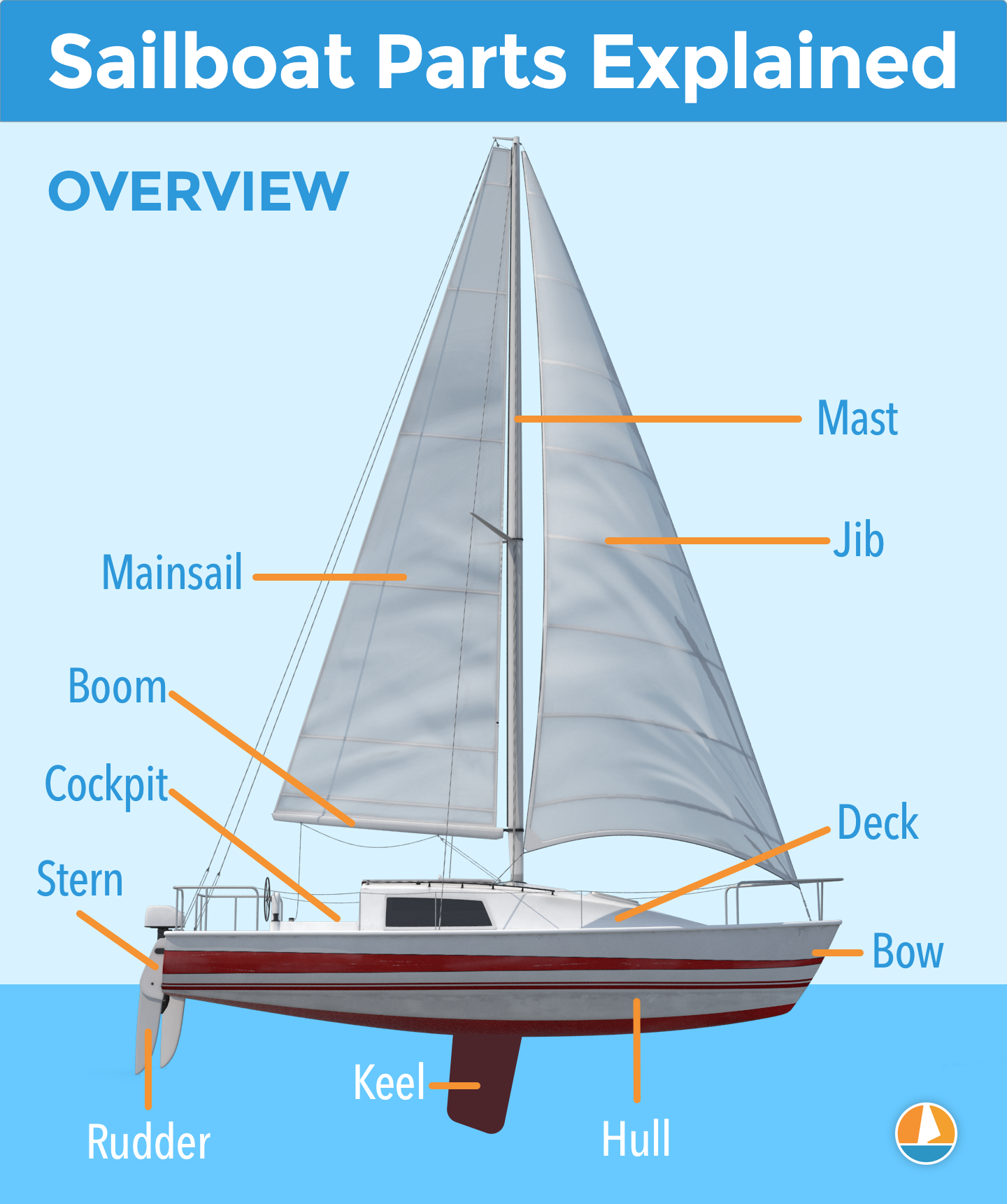

Sailboat Parts Explained: Illustrated Guide (with Diagrams)

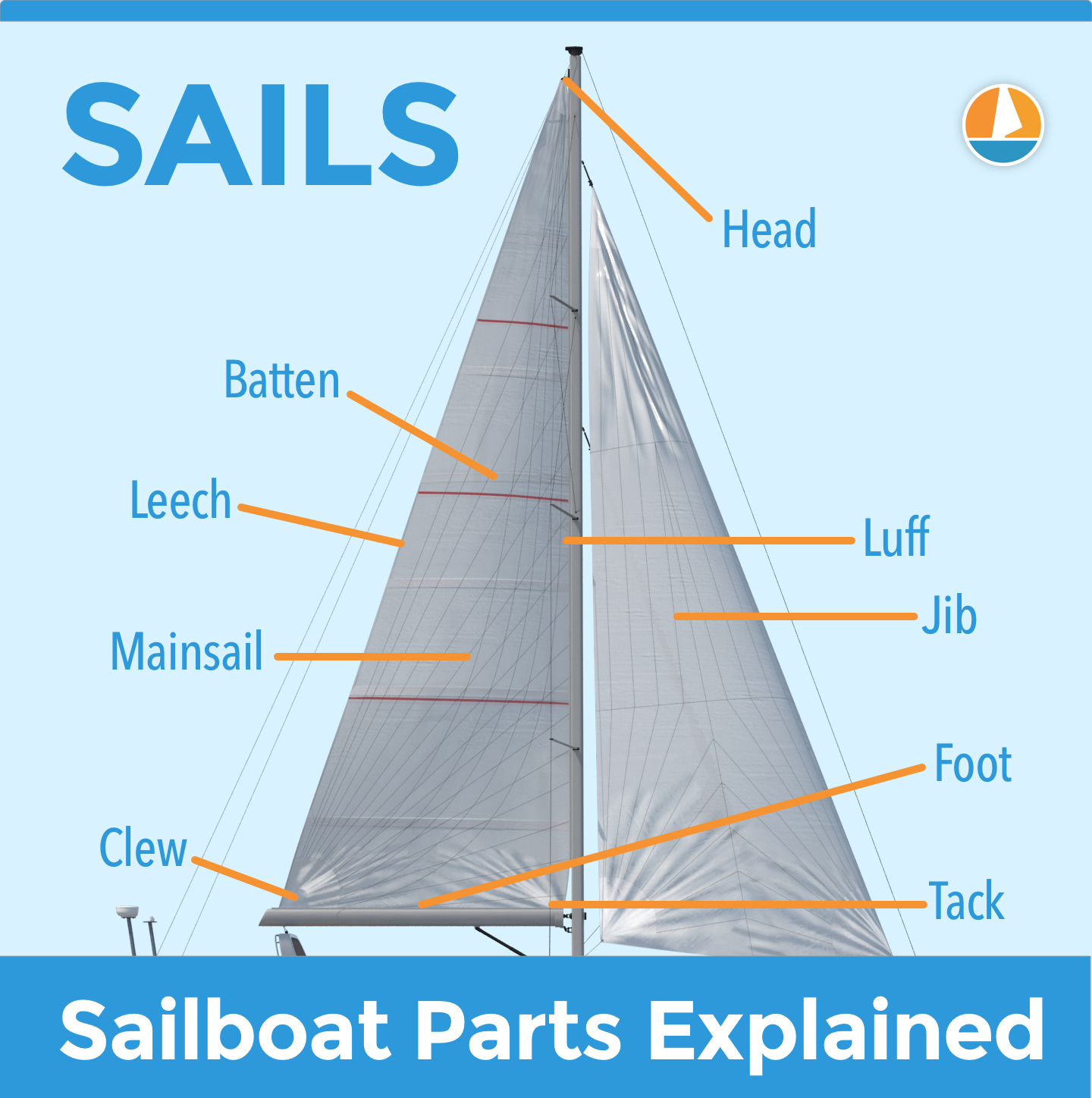

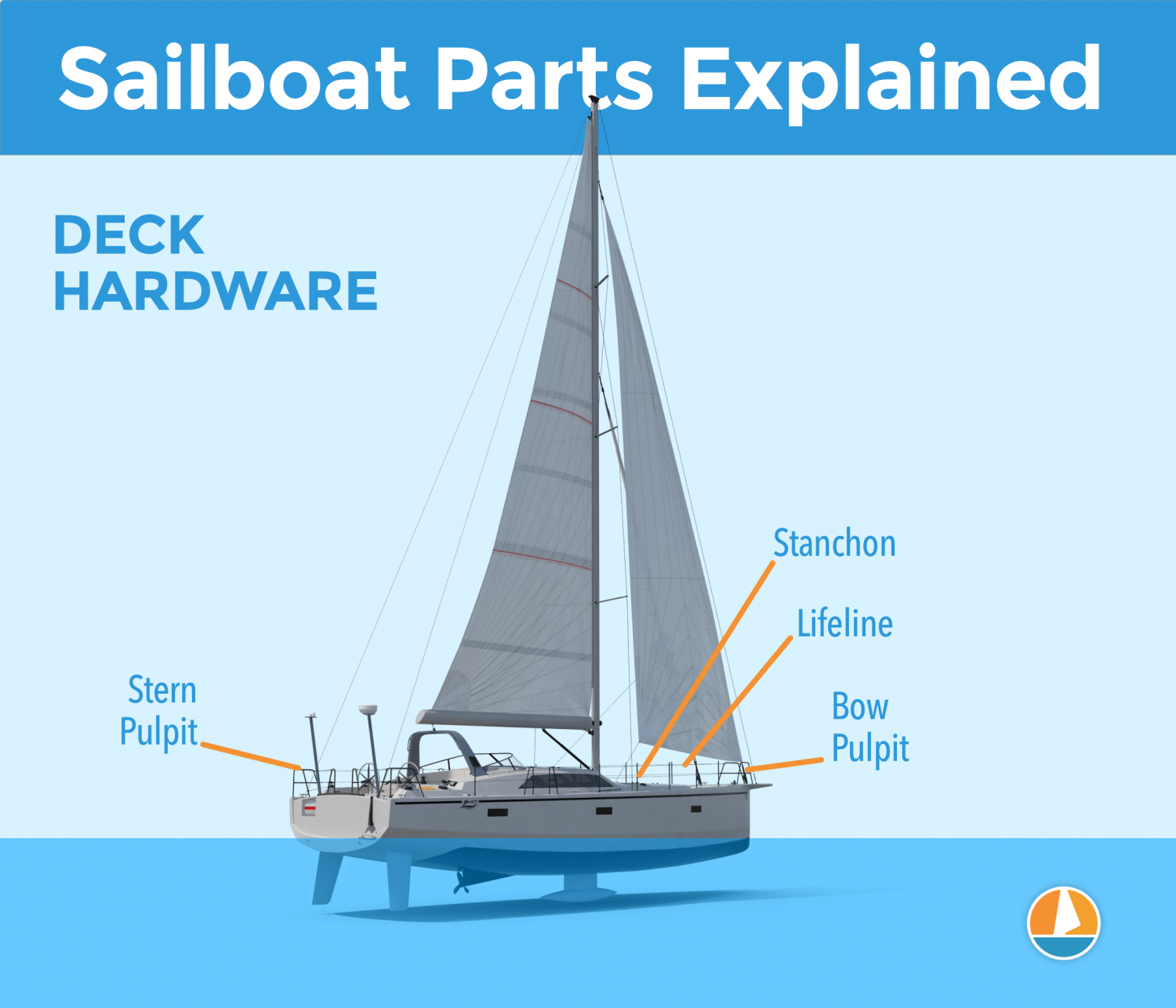

When you first get into sailing, there are a lot of sailboat parts to learn. Scouting for a good guide to all the parts, I couldn't find any, so I wrote one myself.

Below, I'll go over each different sailboat part. And I mean each and every one of them. I'll walk you through them one by one, and explain each part's function. I've also made sure to add good illustrations and clear diagrams.

This article is a great reference for beginners and experienced sailors alike. It's a great starting point, but also a great reference manual. Let's kick off with a quick general overview of the different sailboat parts.

General Overview

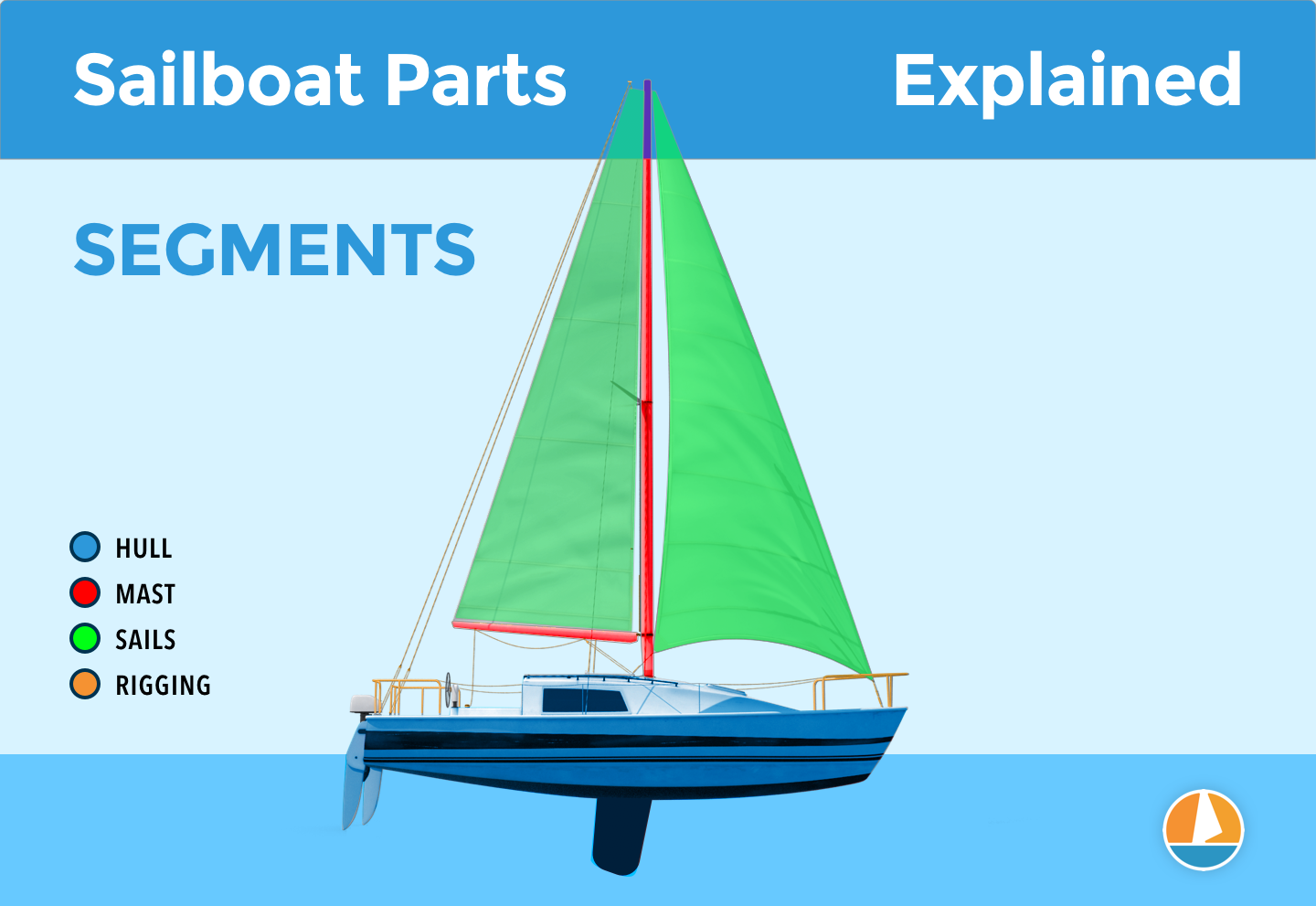

The different segments

You can divide up a sailboat in four general segments. These segments are arbitrary (I made them up) but it will help us to understand the parts more quickly. Some are super straightforward and some have a bit more ninja names.

Something like that. You can see the different segments highlighted in this diagram below:

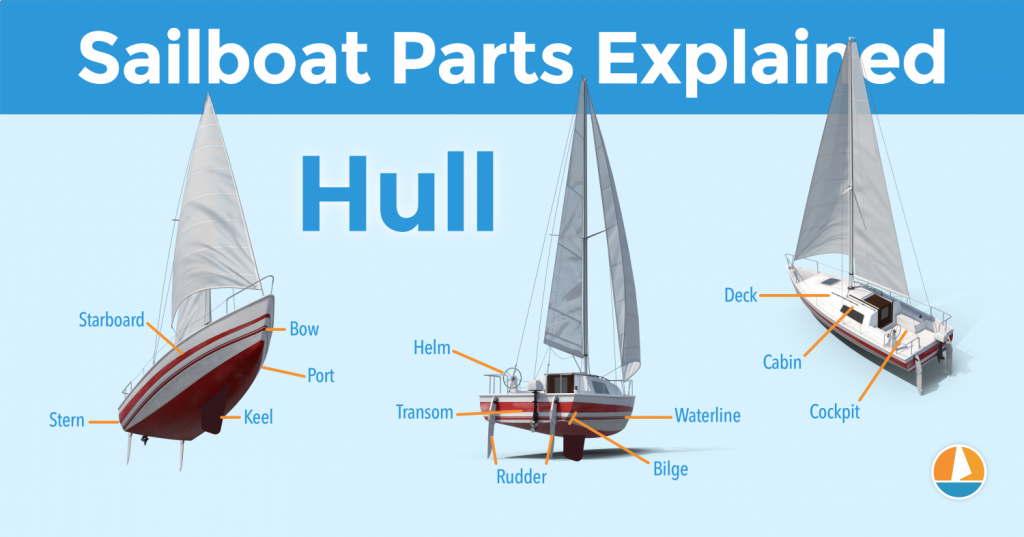

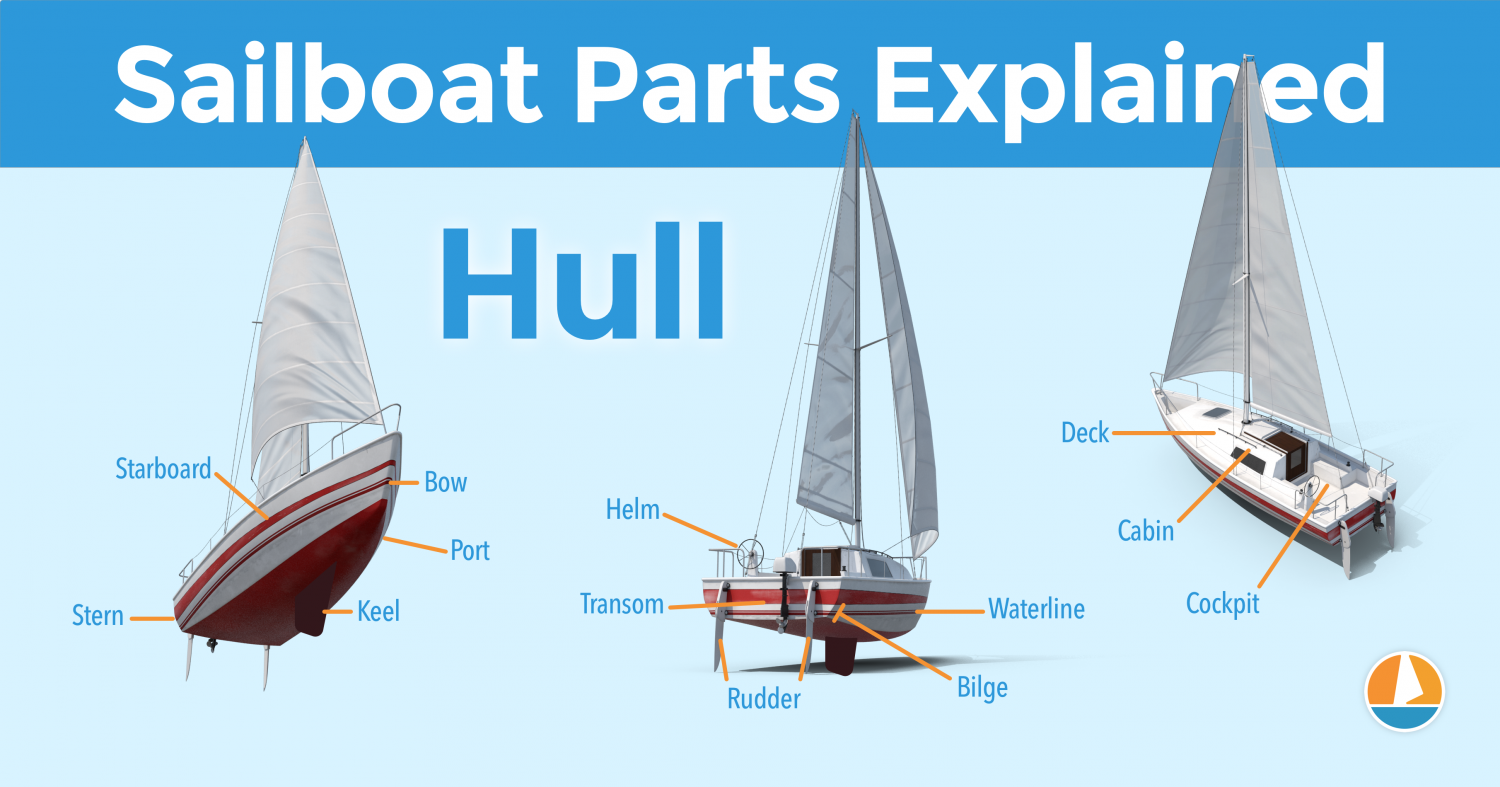

The hull is what most people would consider 'the boat'. It's the part that provides buoyancy and carries everything else: sails, masts, rigging, and so on. Without the hull, there would be no boat. The hull can be divided into different parts: deck, keel, cabin, waterline, bilge, bow, stern, rudder, and many more.

I'll show you those specific parts later on. First, let's move on to the mast.

Sailboats Explained

The mast is the long, standing pole holding the sails. It is typically placed just off-center of a sailboat (a little bit to the front) and gives the sailboat its characteristic shape. The mast is crucial for any sailboat: without a mast, any sailboat would become just a regular boat.

I think this segment speaks mostly for itself. Most modern sailboats you see will have two sails up, but they can carry a variety of other specialty sails. And there are all kinds of sail plans out there, which determine the amount and shape of sails that are used.

The Rigging

This is probably the most complex category of all of them.