- Senior Living

- Wedding Experts

- Private Schools

- Home Design Experts

- Real Estate Agents

- Mortgage Professionals

- Find a Private School

- 50 Best Restaurants

- Be Well Boston

- Find a Dentist

- Find a Doctor

- Guides & Advice

- Best of Boston Weddings

- Find a Wedding Expert

- Real Weddings

- Bubbly Brunch Event

- Properties & News

- Find a Home Design Expert

- Find a Real Estate Agent

- Find a Mortgage Professional

- Real Estate

- Home Design

- Best of Boston Home

- Arts & Entertainment

- Boston magazine Events

- Latest Winners

- Best of Boston Soirée

- NEWSLETTERS

If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

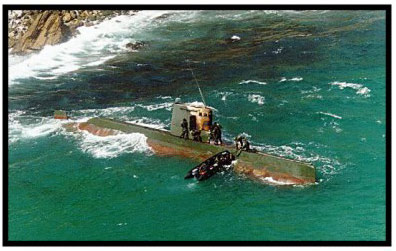

Shipwrecked: A Shocking Tale of Love, Loss, and Survival in the Deep Blue Sea

Illustration by Comrade

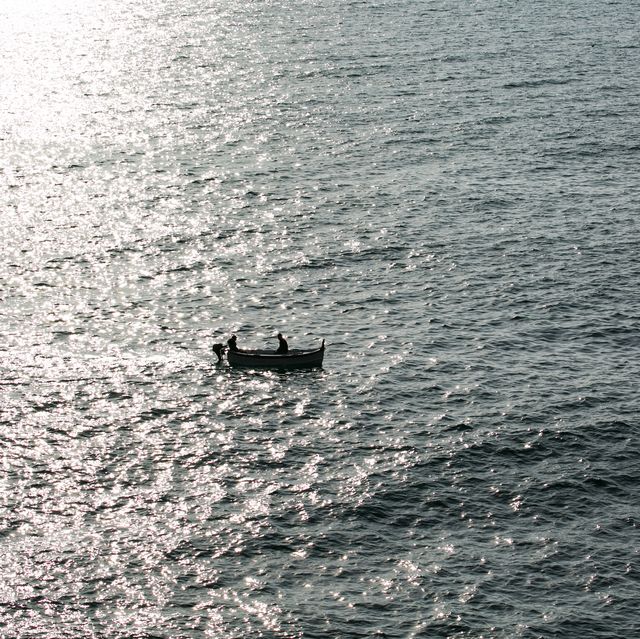

A drift in the middle of the ocean, no one can hear you scream.

It was a lesson Brad Cavanagh was learning by the second. He had been above deck on the Trashman , a sleek, 58-foot Alden sailing yacht with a pine-green hull and elegant teak trim, battling 100-mile-per-hour winds as sheets of rain fell from the turbulent black sky. The latest news report had mentioned nothing about bad weather, but two days into his voyage a tropical storm formed off of Cape Fear in the Carolinas, whipping up massive, violent waves out of nowhere. Soaked to the skin and too tired to stand, the North Shore native from Byfield sought refuge down below, where he braced himself by pressing his feet and back between the walls of a narrow hallway to keep from being knocked down as 30-foot-tall walls of water tossed the boat around the open seas.

Below deck with Cavanagh were four crewmates: Debbie Scaling, with blond hair and blue eyes, was an experienced sailor. As the first American woman to complete the Whitbread Round the World Race—during which she’d navigated some of the most difficult conditions on the planet—she was already well known in professional sailing circles. Mark Adams, a mid-twenties Englishman who had been Cavanagh’s occasional racing partner; the boat’s captain, John Lippoth; and Lippoth’s girlfriend, Meg Mooney, rounded out the crew, who were moving a Texas tycoon’s yacht from Maine to Florida for the winter season.

As the storm continued, Cavanagh grew increasingly angry. At 21 years old and less experienced than most of the others, he felt as though no one had a plan for how they were going to get out of this mess alive. He knew their situation was dire. The motor was dead for the third time on the trip, and they had already cut off the wind-damaged mainsail. That meant nature was in control. They could only ride it out and hope to survive long enough for the Coast Guard to rescue them. Crewmates had been in contact with authorities nearly every hour since the early morning, and a rescue boat was supposedly on its way. It’s just a matter of time , Cavanagh told himself again and again, just a matter of time.

After a while, the storm settled into a predictable pattern: The boat would ride up a wave, tilt slightly to port-side and then ride down the wave, and right itself for a moment of stillness and quiet, sheltered from the wind in the valley between mountains of water. Cavanagh began to relax, but then the boat rose over another wave, tilted hard, and never righted itself. Watching the dark waters of the Atlantic approach with terrifying speed through the window in front of him, Cavanagh braced for impact. An instant later, water shattered the window and began rushing into the boat. He jumped up from the floor with a single thought: He had to rouse Scaling from her bunkroom. He had to get everyone off the ship. The Trashman was going down.

Three days earlier, the weather had been perfect: The sun sparkled on the water and warmed everything its rays touched, despite bursts of cool breezes. Cavanagh was walking the docks of Annapolis Harbor alongside Adams, both of them hunting for work. A job Adams had previously secured for them aboard a boat had fallen through, and all they had to show for it was a measly $50 each. As they made their way along the water, Cavanagh spotted an attractive woman standing by a bank of pay phones. He looked at her and she stared back at him, a sandy-haired, 6-foot-3-inch former prep school hockey player draped in a letterman jacket. It wasn’t until she called out his name that he realized who she was: Debbie Scaling.

Cavanagh came of age in a boating family. He’d survived his first hurricane at sea in utero, and grew up on 4,300 feet of riverfront property in Byfield, where his father, a trained reconnaissance photographer named Paul, taught him and his siblings how to sail from an early age. From the outside, the elite schools, the sailboat, the new car every five years, the grand house, and the self-made patriarch gave the impression that the Cavanaghs were living the suburban American dream. Inside the home, though, it was a horror show. Always drinking, Cavanagh’s father emotionally abused, insulted, and belittled his wife and children, Cavanagh recalls. Whenever Cavanagh heard the clinking of ice cubes in his father’s glass, his stress meter spiked.

Despite that—or perhaps because of it—all Cavanagh ever wanted was his father’s approval. Sailing, he thought, would earn his respect. Cavanagh’s sister, Sarah, after all, had been a star sailor, and at family dinners his hard-drinking—and hard-to-please—father talked about her with pride and adulation. In fact, it was Cavanagh’s sister who had first met Scaling when they raced across the Atlantic together a year earlier. She had recently introduced Scaling to Cavanagh and her family, and now, standing at that pay phone in Annapolis, Scaling could hardly believe her eyes. At that very moment, she had just called Cavanagh’s household in hopes of convincing Sarah to join the crew of the Trashman , and here was Sarah’s younger brother standing right in front of her.

Scaling was desperately looking for help on the yacht. Already things had been going poorly: The boat’s captain, Lippoth, who was a heavy drinker, was passed out below deck when she first showed up at the Southwest Harbor dock in Maine to report for work. Soon after they set sail, they picked up the captain’s girlfriend, Mooney, because she wanted to come along for the trip. From Maine to Maryland, Lippoth rarely eased the sails and relied on the inboard motor, which consistently sputtered and needed repair. They’d struggled to pick up additional hands as they traveled south, and Scaling knew they needed more-qualified help for the difficult sail along the coast of the Carolinas, exposed at sea to high winds and waves. Scaling didn’t share any of this with Cavanagh or Adams when Lippoth offered them a job, though. Happy to have work, the pair accepted and climbed aboard.

Perhaps Cavanagh should have known something was wrong with the yacht when the captain mentioned that the engine kept burning out.

“Mayday! Mayday!” A crew member was shouting into the radio, trying to summon the Coast Guard as the yacht began taking on water. Cavanagh had just burst into Scaling’s cabin, while Adams roused Lippoth and Mooney. And now they huddled together at the bottom of a flight of stairs watching the salty seawater rise toward the ceiling. Lippoth tried to activate the radio beacon that would have given someone, anyone, their latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates, but the water rushing in carried it away before he could reach it.

The crew started making their way up toward the deck to abandon ship. Cavanagh spotted the 11-and-a-half-foot, red-and-black Zodiac Mark II tied to a cleat near the cockpit. The outboard motor sat next to it on the mount, but the yacht was sinking too fast to grab it. As he fumbled with the lines of the Zodiac, one broke, recoiled, and ripped his shirt open. Then he lost his grip on the dinghy, and it floated off. Fortunately, it didn’t go far. Adams wasn’t so lucky. A strong gust of wind ripped the life raft out of his hands, and the sinking yacht started to take the raft and its emergency food, water rations, and first-aid kit down with it. By the time Cavanagh swam off the Trashman , it was nearly submerged.

As Cavanagh made his way toward the dinghy, he kicked off his boots, which belonged to his father. For a moment, all he could think was how angry his dad would be at him for losing them. When he got to the Zodiac, he yelled to the others to grab ahold of the raft before the yacht sucked them down with it. The crew made it onto the dinghy with nothing but the clothing on their backs. As they turned around, the last visible piece of the Trashman disappeared beneath the ocean.

Terrified, the five crew members spent the next four hours in the water, being thrashed about by the waves while holding on to the lines along the sides of the Zodiac, which they had flipped upside down to prevent it from blowing away. During the calmer moments, they ducked underneath for protection from the strong winds, with only their heads occupying a pocket of air underneath the raft. There wasn’t much space to maneuver, but still Cavanagh felt the need to move toward one end of the boat to get some distance from his crewmates while he processed his white-hot anger at Lippoth and Adams. Over the past two days, Adams had often been too drunk to do his job, and Lippoth never did anything about it, leaving him and Scaling to pick up the slack. Cavanagh had spent his childhood on a boat with a drunken father, and now, once again, he’d somehow managed to team up with an alcoholic sailing partner and a captain willing to look the other way.

Perhaps he should have known something was wrong with the yacht when the captain mentioned that the engine kept burning out. Maybe he should have been concerned that Lippoth didn’t even have enough money for supplies. But there was nothing he could do about it now, adrift in the Atlantic and crammed under an inflated dinghy trying to stay alive.

As nighttime approached and the temperature dropped, Cavanagh devised a plan for the crew to seek shelter on the underside of the Zodiac yet remain out of the water. First, he grabbed a wire on the raft and ran it from side to side. He lay his head on the bow of the boat and rested his lower body on the wire. Then the others climbed on top of him, any way they could, to stay under the dinghy’s floor but just out of the water. When the oxygen underneath the Zodiac ran out, they’d exit, lift the boat just long enough to allow new air into the pocket, and go back under again.

Sleep-deprived and dehydrated, Cavanagh’s mind wandered home to Byfield and the endless summer afternoons of his childhood spent under his family’s slimy dock, playing hide-and-seek with friends. Cavanagh had spent a lot of his life hiding from his father and his alcohol-fueled rages. If there was a silver lining to the abuse and the fear he grew up with, it was that he learned how to survive under pressure and to avoid the one fatal strain of seasickness: panic.

The next morning, that skill was suddenly in high demand as Lippoth unexpectedly swam out from under the Zodiac to find fresh air. He said he felt like he was having a heart attack and refused to go back under. The storm had calmed, but a cool autumn breeze was sucking the heat from their wet bodies, and Cavanagh wanted the crew to stay under the boat to keep warm. Disagreeing with him, Cavanagh’s crewmates decided to flip the boat right-side up and climb onboard. It momentarily saved their lives: They soon noticed three tiger sharks circling them.

Mooney had accidentally gotten caught on a coil of lines and wires while abandoning the yacht, leaving a bloody gash behind her knee. Everyone else had their cuts and scrapes, too, and the sharks had followed the scent. The largest shark in the group began banging against the boat, then swam under the craft and picked it up out of the water with its body before letting it drop back down. The crew grabbed onto the sides of the Zodiac while Cavanagh and Scaling tried to fashion a makeshift anchor out of a piece of plywood attached to the raft with the metal wire, hoping that it would help steady the boat. No sooner had they dropped the wood into the water than a shark bit it and began dragging the boat at full speed like some twisted version of a joy ride. When the shark finally spit the makeshift anchor out, Cavanagh reeled it in and Adams, in a rage, grabbed it and tried to smash the shark’s head with it. Cavanagh begged his partner to calm down. “The shark’s reaction to that might be bad,” he said, “so just cool it.”

Cavanagh believed that if they could all just stay calm enough to keep the boat upright, they could make it out alive. “The Coast Guard knows we’re here,” Cavanagh told the others, who had heard a plane roaring overhead before the Trashman sank. It was presumably sent to locate any survivors so a rescue ship could bring them back to shore. Unknown at the time was that a boat had been on the way to rescue the group, when for some reason—a miscommunication of sorts—the search was either forgotten or called off. No one was coming for them.

Brad Cavanagh is still haunted by his fight for survival. / Portrait by Matt Kalinowski

Fighting to survive, Cavanagh knew he needed to keep his mind and body busy. With blistered lips and cracked hands, he pulled seaweed onboard to use as a blanket, and he flipped the boat to clean out the urine and fetid water that had accumulated in it. First, he scanned the water to make sure the sharks had left. Then, with Adams’s help, he leaned back and tugged on the wire to flip the boat, rinsed it out, and flipped it back over again so everyone could climb back in. He had a job and a purpose, and it kept him sane.

The others struggled. Adams and Lippoth were severely dehydrated. (Adams from all the scotch he drank and Lippoth from the cigarettes he chain-smoked before the Trashman went down.) Meanwhile, Mooney’s cut was infected and filled with pus; she was getting sicker and weaker. As they lay together in a small pool of water in the bottom of the boat, they all developed body sores, likely from staph infections. Cavanagh’s skin became so tender that even brushing up against another person sent a current of pain through his body. After three days without food and water and using their energy to hold on to the Zodiac during the storm, they were all completely spent.

Realizing that the Coast Guard may not be coming after all, some crew members began to believe their only hope for survival was to eventually wash up on shore. What they weren’t aware of was that a current was pulling them even farther out to sea.

That night, Cavanagh dreamt of home. He was on a boat, sailing, and talking to the men on a fishing vessel riding along next to him as he made his way from Newburyport to Buzzards Bay. It was the route his family took when moving their boat every summer.

The day after he had that dream, the situation descended into a nightmare: Lippoth and Adams began drinking seawater. It slaked their thirst momentarily, but Cavanagh knew it would only be a matter of time before it sent them deeper into madness. Soon enough, the delusions began. First, Lippoth started reaching around the bottom of the boat looking for supplies that didn’t exist. “We bought cigarettes. Where are they?” Lippoth asked. Then Lippoth began trying to convince Mooney that they were going to take a plane to Maine, where his mother worked at a hospital. “We’re going to Portland,” he told her. “I’m going to get the car. I want you guys to pick up the boat and I’ll come back out and get you,” Lippoth said before sliding over the edge of the Zodiac and into the water.

“Brad, you’ve got to get John,” Scaling said to Cavanagh in a panic. But Cavanagh was so weak, he could barely muster the energy to coax Lippoth back onboard. “If you go away and die, then I might die, too. I don’t want to die,” Cavanagh pleaded.

It was too late. The wind pulled the Zodiac away from him. The captain soon drifted out of sight. Across the empty expanse of the ocean, Cavanagh could hear Lippoth’s last howls as the sharks attacked.

An old newspaper clipping of Cavanagh and Scaling, not long before their rescue. / Courtesy photo

Now there were four. Cavanagh, though, noticed Adams was quickly careening into madness, hitting on Mooney, and proposing that sex would cheer her up. Rebuffed, he decided to take his party elsewhere. “Great,” Cavanagh recalls him saying, “if we’re not going to have sex, I’m going back to 7-Eleven to get some beers and cigarettes.”

“You’re not going,” Cavanagh said. “We’re out in the middle of the ocean.”

“I know, I know,” he told Cavanagh. “I’m just going to hang over the side and stretch out a little bit. I’ll get back in the boat.”

Holding onto the side of the raft, Adams slipped into the water. Cavanagh looked away for a moment to say something to Scaling, and when he turned back, Adams was gone. Soon after, the boat began to spin and the water around them started to churn wildly. Cavanagh knew the sharks had gotten Adams, but he was so focused on surviving that it hardly registered that his racing buddy was gone forever.

The three remaining castaways spent the rest of the evening being knocked around as the sharks bumped and prodded the boat. They found something they like , Cavanagh said to himself. And now they want more.

Mooney lay there shivering violently from the cold. In the black of night, she lurched at Cavanagh, scratching at him and screaming. Then she began speaking in tongues. In the morning, Cavanagh woke first and found her lying on her back, her arms outstretched, staring into the sky. “She’s dead,” Cavanagh said when Scaling woke up. “She’s been dead for hours.”

Then a terrifying thought came to his mind: Maybe we could eat her . He was so hungry, so desperately famished, but her body was covered in sores and oozing pus.

Cavanagh and Scaling removed Mooney’s shirt so they would have another layer to keep warm, and her jewelry so they could return it to her family. They still hoped they would have that chance. Then they pushed her naked body off the raft. She floated like a jellyfish, with her arms and legs straight down, away and over the waves. Neither of them were watching when the sharks came for her, too.

After Mooney died, Scaling was troubled that she was lying in pus-infected water and begged Cavanagh to flip the boat over and clean it out. Weak and unsteady, he agreed to try. Standing on the edge of the Zodiac, he tugged the wire and tried to flip it, but he didn’t have the strength to do it alone. Then he gave another tug, lost his balance, and tumbled backward into the water. He tried to get back in the boat but couldn’t. Panic seized him. Every person who had come off that boat had been eaten by sharks. He needed to get back in fast, and he needed Scaling’s help.

Cavanagh begged her to help him up, but she only sat there sobbing inconsolably on the other side of the raft. With his last bit of strength, Cavanagh willed himself over the side on his own. He sat in the boat, winded and seething with anger. The entire time, from when they were on the Trashman with a drunken crewmate, during the storm, and throughout their harrowing journey on the Zodiac, Scaling and Cavanagh had upheld a pact to look out for each other, to protect each other from the sharks, the madness, the others. How could she have left me there in the water? he thought. How could she have let me down? They were supposed to be a team. Now on their fifth day without food or water, he couldn’t even look at her. There were two of them left, but he felt alone.

They sat in a cold, uncomfortable silence until he had something important to say. “Deb, look,” Cavanagh shouted. A large vessel was approaching them. They’d spotted a couple of ships before in the distance, but none were close enough for them to be seen. As it moved toward them, he could see a man on the deck waving. Shortly after, crew members threw lines with large glass buoys on the end of them. But they all landed short, splashing in the water too far away. Undeterred, the men on deck pulled the rescue buoys back and tried again.

Cavanagh, for his part, couldn’t move. “I’m not going anywhere,” he told Scaling. It felt as if every muscle had gone limp. He had nothing left after spending days balancing the boat, flipping it, pulling it, and watching his crewmates die. The ship made another turn. Closer. The men aboard threw the lines again. Scaling jumped into the water and started swimming.

Seeing his crewmate in the water was all the motivation Cavanagh needed. Fuck it , he told himself. Here I go . He rolled overboard and managed to grab a line, letting the crew reel his weakened body in and hoist him up onto the deck along with Scaling. Aboard the ship, Cavanagh saw women wearing calico dresses with aprons and steel-toed work boots waiting for them. They were speaking Russian. At the height of the Cold War, the U.S. Coast Guard never came to save them, but ice traders on a Soviet vessel did.

The crew gave Cavanagh and Scaling dry clothes and medical attention, along with warm tea kettles filled with coffee, sugar, and vodka. That night, as the Coast Guard finally arrived and spirited the two survivors to a hospital, the temperature dropped down into the 30s. Cavanagh and Scaling wouldn’t have made it through another night at sea.

As Cavanagh was recuperating in the hospital, his mother flew down to be by his side. Seeing her appear at his bedside felt like the happiest moment of his life. His father, however, never came; he was on a sailing trip.

Cavanagh soon returned home to Massachusetts and once again felt the need to keep busy: He immediately began taking odd jobs in hopes of earning enough cash to begin traveling to sailboat races again. Processing what he’d endured—five days without food or water and man-eating sharks—was next to impossible. The Southern Ocean Racing Conference season in Florida started in January, and he was determined to be there, but not necessarily to race. He needed to talk to the only other person who had made it off that Zodiac alive. He had something important he needed to tell Scaling.

A few months later, Cavanagh boarded a flight to Fort Lauderdale for the event. With no place to stay, he slept in an empty boat parked in a field. Walking around the next day, he caught a glimpse of the latest issue of Sail magazine and stopped dead in his tracks: Staring back at him was a photo of him and Adams, plastered across the cover. A photographer had snapped a shot of the two racing buddies just before they’d joined the Trashman . It was like seeing a ghost.

Cavanagh paced the docks searching for Scaling—then there she stood, looking as beautiful as ever. His whole body was pumping with adrenaline at the sight of his former crewmate. He needed to tell her he was in love with her. They had shared something that no one else could ever understand. The bond he felt was far deeper than any he’d ever known.

He moved toward her to speak, but the mere sight of Cavanagh made Scaling recoil, reminding her of the horrors that she’d suffered at sea while in the Zodiac. “I’m sorry, but I cannot be around you,” he recalls her saying. “I don’t want you to have anything to do with me. Please leave me alone.” Dejected and hurt, Cavanagh retreated. Then he did what he’d always done: He walked the docks, banging on boats until he found someone willing to hire him.

As the years rolled by like waves, Scaling became a socialite and motivational speaker, talking publicly and often about her fight to survive. She appeared on Larry King Live and wrote a memoir. She and Cavanagh both continued to sail and ran in similar circles, seeing each other often, and both trying desperately to hide their pain when they did.

Scaling eventually settled down in Medfield, where she raised a family and spent summers on the Cape. In 2009, her son, also an avid sailor, drowned in an accident. Nearly three years to the day later, she passed away in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, at 54. Cavanagh was walking out of a marina in Newport, Rhode Island, when someone broke the news to him. He was profoundly disappointed. Disappointed with life itself. He had loved her. There was no information in her obituary about her cause of death, but he recalls there were whispers among family members of suicide. Cavanagh believed no one could have saved her: She was still tortured by those days lost at sea. He was now the lone survivor of the Trashman tragedy.

Several years later, Scaling’s daughter gave Cavanagh a frame. Inside it was a neatly coiled metal wire—the same one Cavanagh had rigged up to suspend their shivering bodies under the Zodiac and flip the boat to keep it clean. It was what had kept them both alive. Unbeknownst to him, Scaling had retrieved it after the dinghy was found still floating in the ocean. She framed it and hung it on her wall, keeping it close all those years.

Cavanagh remains hell-bent on learning why the Coast Guard never showed up in the aftermath of that fateful storm.

On a cold winter day, I drove to Cavanagh’s home in Bourne, where he lives with his wife, a schoolteacher, and his two children. He still had wide shoulders and a strong face, now layered with deep wrinkles, and greeted me with a handshake. His enormous hands engulfed mine.

The wind howled outside and a fire burned in the living room’s gas stove as he sat down on his couch to talk—for the very first time at length—about his life since being rescued. Above his head was the rendering of a floating school he once wanted to build for the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. It had classrooms, living quarters for the students, and bathrooms, but it never was built. It became one of Cavanagh’s many grand ideas over the years, all of which had to do with sailing, that he never saw to fruition. He wants to write a book, too, like Scaling, but he hasn’t been able to get started.

Sailing is the one thing that has remained constant in Cavanagh’s life. He said the ocean continued to give him freedom, even as he remained chained to his past, to the shipwreck that almost killed him, and to the abusive father who failed him.

While we sat there, listening to the wind, Cavanagh pulled out his father’s sailing logbook. In it were the dates and locations of his around-the-world trip. The day his father set sail in 1982, Cavanagh thought he was finally safe. His mother had just filed for divorce and Cavanagh no longer felt he had to stick around to protect her, so he left home to start his life. His father had invited him to join him on his trip, but there was no way Cavanagh was doing that. He wound up on the Trashman instead.

Cavanagh paused to read his father’s entries from the days that Cavanagh was lost at sea. At the time, his father had been docked and drunk in Bermuda, which lies off the coast of the Carolinas, just beyond where the yacht went down. Then he set sail again into the weakened tail end of the same storm that had sunk the Trashman , not knowing that his son had been floating in that same ocean, fighting for his life and waiting for someone to save him.

Cavanagh remains hell-bent on learning why the Coast Guard never showed up in the aftermath of that fateful storm. He has documents and photos from the official case file after the sinking of the Trashman , but they give few, if any, clues. He has spent decades trying to figure out what happened, and now that he’s the only crew member alive, he’s even more determined to find the truth. He wants to know how rescuers forgot about him and his crewmates, and why. Haunted by his memories, he has driven up and down the East Coast, stopping at bases and looking for anyone to speak to him about the incident. He is still adrift, nearly 40 years later, still searching for answers.

Hundreds of ships go missing each year, but we have the technology to find them

Senior Lecturer in Astronomy, University of Leicester

Disclosure statement

Nigel Bannister works for the University of Leicester. He received funding from US Office of Naval Research - Global to conduct this work.

University of Leicester provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

The seas are vast. And they claim vessels in significant numbers. The yachts Cheeki Rafiki , Niña , Munetra , Tenacious are just some of the more high-profile names on a list of lost or capsized vessels which grows by hundreds each year.

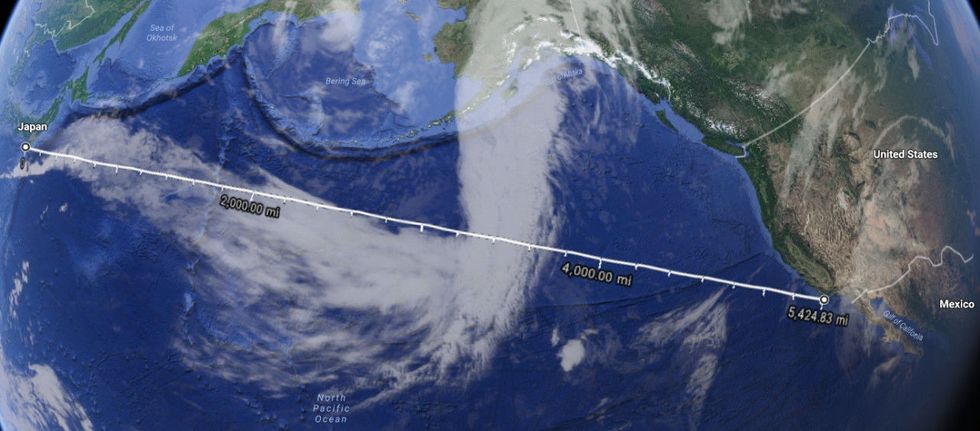

Yet it took the disappearance of flight MH370, now declared lost with no survivors , to demonstrate how difficult it can be to find something in the open ocean. As the search continued, incredulity grew: exactly how, in the 21st century, is it possible to lose a 64-metre aircraft?

There are great unknowns at sea: planes and boats go missing. Illegal fishing and piracy are easy to conduct – and small vessels can smuggle powerful weapons and dangerous individuals. The technology to improve this situation already exists, we just need to make better use of it.

The view from above

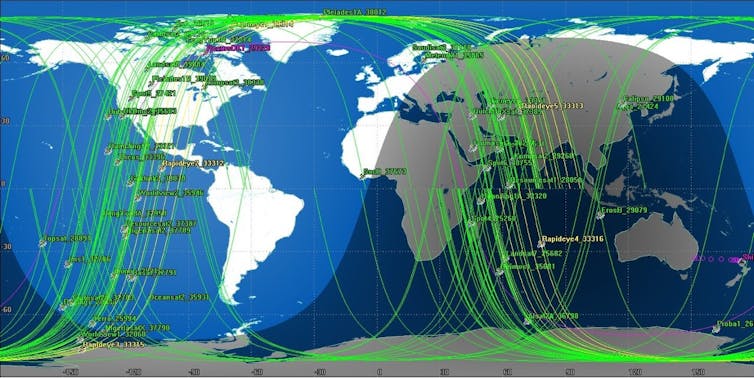

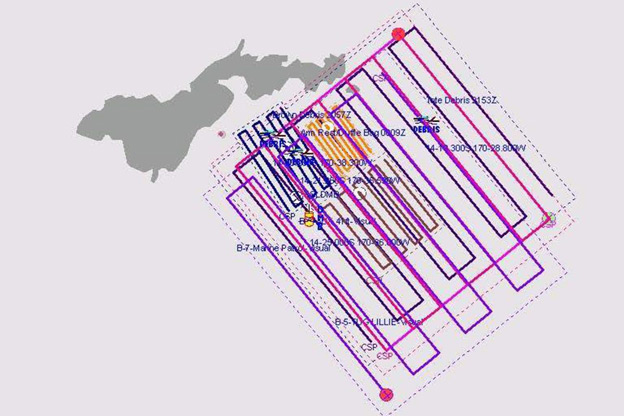

Satellites provide the vantage point necessary to monitor large areas of ocean. Spacecraft carrying synthetic aperture radar (SAR) can provide high-quality images with resolution down to a metre, regardless of the weather. But the relatively small number of spacecraft equipped with SAR, and the dawn-to-dusk orbits which most occupy, also limit the times of day when they can provide coverage.

To offer comprehensive monitoring at sea, we need to bring together different types of imaging, including radar and photographic images in the human-visible wavelength. This is often overlooked for maritime purposes due to the effects of cloud, rain, and darkness that limit its use. But there are enough satellites with the capability that could provide excellent coverage.

Detail and coverage

The two key requirements for effective monitoring are high spatial resolution (good detail) and a large field of view (wide area). One tends to come at the expense of the other, so that a device – whether it is a camera, satellite or radar – capable of detecting small vessels will usually only be able to scan an area a few tens of kilometres wide, making it both unlikely that the search area of interest has been recorded and rendering subsequent searches very slow.

But the situation is changing. The number of imagers is growing rapidly. In our recently published study , we identified 54 satellites carrying 85 sensors which offer useful resolution and could be accessed commercially (excluding military surveillance spacecraft). Companies such as PlanetLabs are in the process of launching many more.

While each satellite’s imaging device generates an image track only 10-100km across, the motion of the satellite as it orbits the Earth effectively “scans” that track so that the image is narrow in one dimension but circles the world in the other. With orbital periods of around 90 minutes, one satellite makes around 16 passes over the daylit hemisphere every day. The combined imaging work of all these satellites now make a significant contribution to our awareness of maritime traffic.

Image early, image often

Imagery used in search-and-rescue operations is usually taken after the target is lost. In the case of the Niña which disappeared off the coast of New Zealand, eight days elapsed between last radio contact and the alarm being raised. For MH370, the search area evolved over periods of weeks. In both cases, ocean currents carry evidence away from the accident site, while debris disperses and sinks, making it more difficult to identify by satellite.

It would be far better to have an archive of recent, regularly updated images so that the recent history of a location over a period of several days can be examined. This could offer evidence of the vessel’s course or state, or pick up on areas of fresh, concentrated debris.

Making the best of what we have

Satellites with visible wavelength cameras are generally used for gathering images of land. What if satellite operators could generate revenue by taking images of the oceans? The limited resources on satellites mean that it isn’t generally possible to constantly take images, to store that data and transmit it all in the next available contact with the ground (which may be some time after an image is acquired). As it is, it’s not possible to create a global maritime monitoring system of this kind without purpose-built spacecraft with bigger data storage and more frequent contact with ground stations to download it.

But it is possible to monitor high-priority areas of heavy traffic, protected fisheries and security-critical regions, with co-operation between operators of existing spacecraft (for which there are precedents such as George Clooney’s Satellite Sentinel Project , which uses satellites to gather evidence of atrocities and war crimes), and incentives, perhaps involving maritime insurance companies.

Retrieving hundreds of gigabytes of data a day from satellites requires a new approach to ground stations. One solution may be to “crowdsource”: to create a network of stations operated by small institutions, universities and individuals to spread the burden of downloading data and increasing the periods during which data can be recorded and transmitted.

There are groups working on automated vessel-detection algorithms – and crowdsourcing also has a role here, such as TomNod , for example, which asked members of the public to help inspect images online in the search for Niña. How much more effective could search and rescue be if the power of crowdsourcing was applied to each stage of data acquisition, storage and processing, combined with high-quality images taken around the time the vessel was lost?

- satellite tracking

- Missing aircraft

- Search and Rescue

- Maritime security

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Associate Director, Operational Planning

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

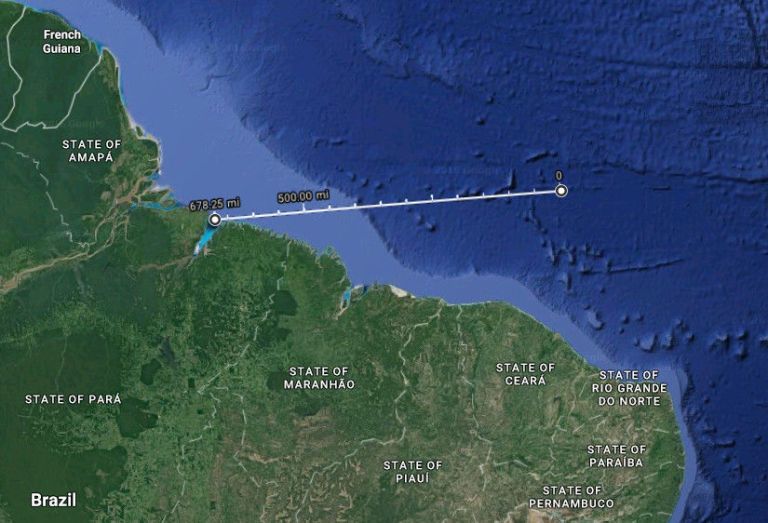

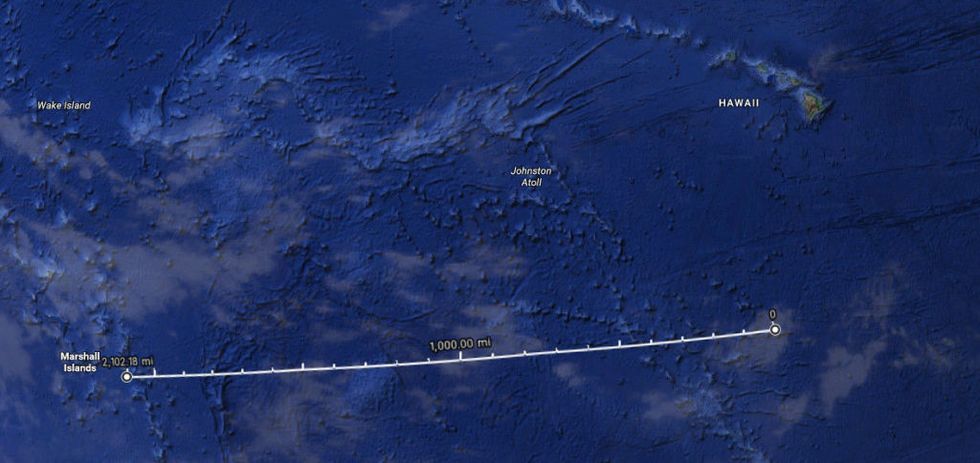

Search for 3 missing American sailors off coast of Mexico has been suspended: US Coast Guard

They had not contacted friends, family or maritime authorities since April 4.

The search for three Americans missing off the coast of Mexico has been suspended, the U.S. Coast Guard said Wednesday.

"An exhaustive search was conducted by our international search and rescue partner, Mexico, with the U.S. Coast Guard and Canada providing additional search assets," Coast Guard Cmdr. Gregory Higgins said in a statement . "SEMAR [The Mexican Navy] and U.S. Coast Guard assets worked hand-in-hand for all aspects of the case. Unfortunately, we found no evidence of the three Americans' whereabouts or what might have happened. Our deepest sympathies go out to the families and friends of William Gross, Kerry O'Brien and Frank O'Brien."

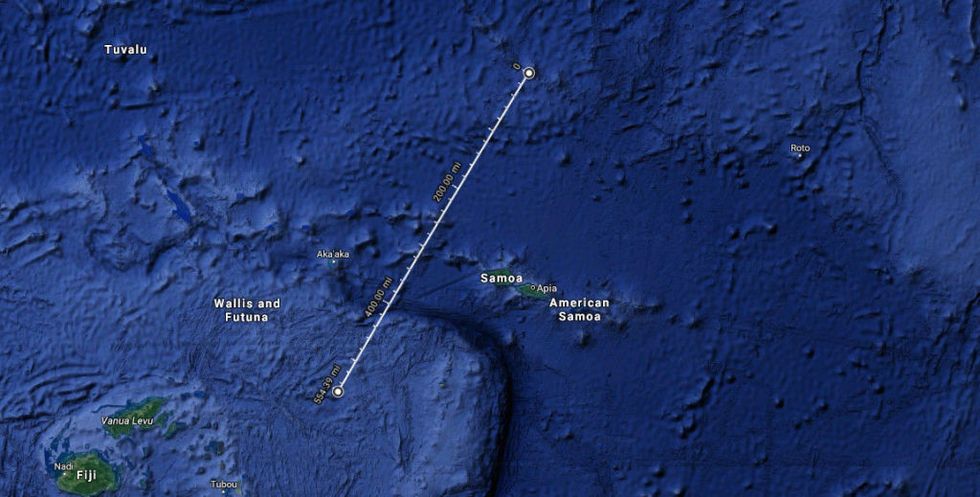

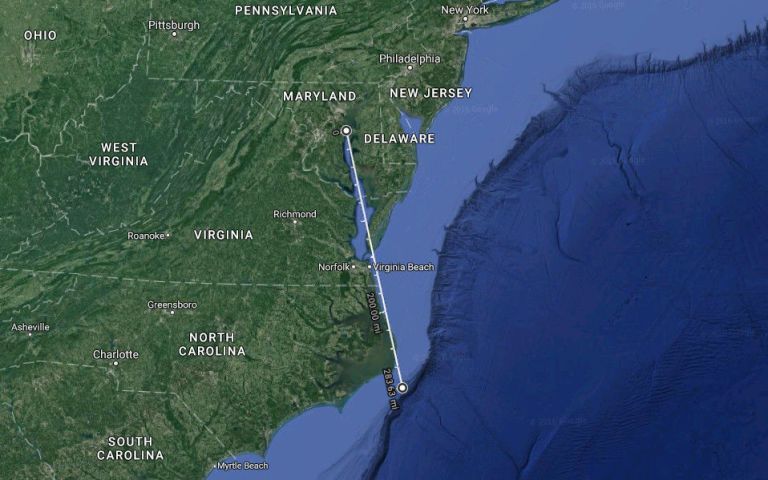

The Mexican Navy and Coast Guard spent "281 cumulative search hours covering approximately 200,057 square nautical miles, an area larger than the state of California, off Mexico's northern Pacific coast with no sign of the missing sailing vessel nor its passengers," the Coast Guard said.

Kerry O'Brien, Frank O'Brien and Gross had not contacted friends, family, or maritime authorities since April 4.

The trio likely encountered "significant" weather and waves as they attempted to sail their 41-foot sailboat from Mazatlán to San Diego.

"When it started to reach into five, six, seven days and we started to get a little more concerned," Kerry's brother Mark Argall told ABC News.

Higgins had expressed concern that the weather in that region worsened around April 6, with swells and wind creating waves potentially over 20 feet high. The three were sailing a capable 41-foot fiberglass boat, with similar sailboats successfully circumnavigating the planet. However, the lack of clear information about the sailors' location, partially attributable to the lack of GPS tracking and poor cellular service near the Baja peninsula, has left the families of the missing Americans uncertain about their loved ones' whereabouts.

"We have all been spinning our wheels about the different scenarios that could have happened," Gross' daughter Melissa Spicuzza said.

Kerry and Frank O'Brien, a married couple, initially decided to travel to Mexico to sail a 41-foot LaFitte sailboat named "Ocean Bound" to San Diego after the boat underwent repairs near Mazatlán, Mexico, according to Argall.

MORE: 6 children rescued near water diversion tunnel in Auburn, Massachusetts

The couple decided to hire Gross, a mechanic by trade and sailor with more than 50 years of experience, to help navigate the boat from Mazatlán to San Diego. Spicuzza recounted that friends of Gross would compare him to the 1980s fictional television character and improvisational savant MacGyver based on his ability to repair boats.

"Whatever it takes, he'll get it rigged up. He'll get it working," Spicuzza described.

The Coast Guard believed the sailors left their slip (the equivalent of a parking spot for boats) on April 2. They eventually departed Mazatlán on April 4, based on Facebook posts and cellphone usage.

The sailors expected the trip across the Gulf of California to Cabo San Lucas, where they planned to pick up provisions, would take two days. However, the Coast Guard does not believe the sailors ever stopped in Cabo San Lucas. Since April 4, marinas throughout the Baja Peninsula have not contacted the vessel, nor have any search and rescue crews spotted it.

According to Higgins, the weather worsened around April 6, with winds of 30 knots, strong swells, and waves making navigation more challenging. Spicuzza added that the sail from Mexico to California is inherently tricky since sailors need to navigate against the wind and current.

"From the tip of Baja all the way back up to Alaska, you're going against wind and current, so it's a more difficult, exhausting sail, but of course, doable with the experience that's on board," Spicuzza.

MORE: 1,200 aboard 2 migrant boats rescued in Mediterranean

Spicuzza added that the group's initially planned 10-day journey was likely unrealistic. Sailing against the wind and current would require the sailors to tack frequently, essentially zig-zag to make progress despite sailing into the wind, which could extend the journey to two and half weeks.

Moreover, according to the Coast Guard, the boat lacks trackable GPS navigation, such as a satellite phone or a tracking beacon. The limited cellular service in that region of Mexico also makes triangulating the cell position difficult.

Robert H. Perry, the designer of the 41-foot sailboat, noted that their boat was likely manufactured in Taiwan 35 years ago. Despite its age, the fiberglass sailboat itself was a time-tested, ocean-navigating boat.

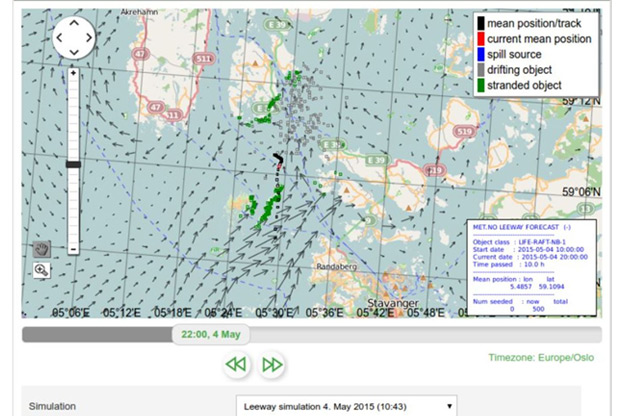

The travel circumstances have left family members uncertain about the status of their loved ones. Based on the timing, it appears possible they are "just going to roll into San Diego like nothing happened in maybe about a week," Spicuzza suggested, with the radio silence attributable to some electronic issue. Alternatively, the Coast Guard has worked on plotting where their life raft might have drifted under current weather conditions.

"It's just been a roller coaster of emotions the last several days; I want my dad home, I want him safe, [and] I want the O'Brien's home safe," Spicuzza said. "I'm very much looking forward to sitting around a table with all of them and joking about the time they got lost at sea – that is the hope."

ABC News' Elisha Asif, Helena Skinner, Zohreen Shah, Amantha Chery and Marilyn Heck contributed to this report.

NEW ON YOUTUBE: Cash for Clunkers List

Unlucky Billionaire’s $38M Megayacht Falls Off Cargo Ship, Gets Lost at Sea

The 130-foot boat was being transported by boat so it could compete in a boat race elsewhere on the planet. Because first world problems.

We’ve all heard of the unfortunate story of someone losing their car or motorcycle in a freak accident, but what about losing a $38-million megayacht ? Various international news outlets report that a 130-foot sailing yacht named MY Song was recently lost in the Mediterranean Sea after falling off a cargo ship while in transport.

You’d think that a boat that fell off another boat would just land in the water and float after suffering some minor damage, right? Unfortunately, this was not the case. According to reports, MY Song fell off its transport freighter and plunged into the Mediterranean after being hit by an unexpected severe storm. Thankfully, it didn’t sink all the way to the bottom, but it did sustain significant damage. Recent reports claim the yacht was last spotted drifting about 40 miles north of the island of Menorca with nearly half of its hull submerged under water.

The boat is owned by Italian billionaire Pier Luigi Loro Piana, and it was on its way to the Loro Piana Superyacht Regatta in Porto Cervo in Sardinia, Italy. It was supposedly being transported on a massive freighter after spending some time sailing around North America.

Pier Luigi is the grandson of Pietro Loro Piana, the founder of an ultra high-end clothing company. Forbes last reported Loro Piana’s net worth at around $1.6 billion.

MY Song’s construction completed in 2016 and in the following year, it won the 2017 World Superyacht Award for the “Best Sailing Yacht ” in its class and size. It also set a speed record while participating in the RORC Transatlantic Race, a 3,000 nautical mile journey from the Canary Islands to Grenada. The boat beat the previous record by nearly 1 hour and 20 minutes. Its mast is over 56 meters tall and the boat was capable of speeds of up to 30 knots.

"We were informed of the loss of a yacht from the deck of the MV Brattinsborg at approximately 0400hr LT on 26th May 2019. The yacht is sailing yacht My Song," said David Holley in an official statement, the chief executive of the logistics company responsible for transporting MY Song. "Upon receipt of the news Peters & May instructed the captain of the MV Brattinsborg to attempt salvage whilst third-party salvors were appointed."

What’s Wrong With All the Ships?

Do recent boat disasters actually point to a global shipping industry in distress?

Are the boats okay?

They seem to be in a tough stretch. A ship called the Felicity Ace is currently afire and adrift in the Atlantic Ocean, off the Azores, with a reported 4,000 cars on board, including Porsches, Bentleys, and Audis. The crew abandoned the vessel, en route to the United States, last week, and firefighters are now trying to control the blaze.

In January, a different container ship, the Madrid Bridge, limped into the port of Charleston, South Carolina, after losing about 60 containers at sea. Pictures of the vessel showed one row of the metal boxes collapsed and teetering over the gunwale. Among the cargo lost : highly anticipated print runs of cookbooks from Mason Hereford and Melissa Clark.

A week later, an oil-storage vessel exploded off the coast of Nigeria. Within days, a Mauritian oil tanker had run aground off Reunión in the Indian Ocean. In Peru, workers are still cleaning up a spill that, according to some accounts, occurred when a tanker was rocked by tsunami waves. Experts are nervously watching another tanker off the coast of Yemen, which is slowly disintegrating in the midst of a war and an existing humanitarian crisis.

These cases come just months after the spectacle of the Ever Given, a massive container ship that wedged itself into the banks of the Suez Canal, halted shipping for days, and enthralled a world bored to tears with the pandemic. These incidents are transfixing—a little awesome, in the old-fashioned sense , and a little hilarious, in a very contemporary internet-ironic one —but is the global shipping industry in some sort of collapse?

Read: The big, stuck boat is glorious

The short answer is no. “It’s just that people have noticed,” John Konrad, the CEO of the shipping site gCaptain , told me. Over the past few years, about 50 major ships have been lost annually. (Comprehensive figures from 2021 are not available yet, but Konrad said he doesn’t see evidence of any big jump last year.) Most of the time, the public has no reason to pay attention to these sinkings and collisions. But supply-chain crunches caused by the pandemic have made the shipping system more visible than it has been for decades, spotlighting cases like the Felicity Ace and Madrid Bridge. Meanwhile, more volatile weather caused by climate change and ever-larger container ships mean the risk of losses may be rising.

Until recently, major nautical disasters could seem like a relic of the past, like train wrecks or dirigible crashes. Every year, the German insurance giant Allianz issues a report on shipping and safety, and it captures steady improvement. As recently as 2000, more than 200 big ships were lost. (Don’t call them “boats” unless you’re ready to be corrected by cranky old salts.) By the early 2010s, that number had dropped to about 100 a year. In 2021, just 49 were lost, and 2020 saw only 48 losses. Allianz attributes this to “the positive effect of an increased focus on safety measures over time, such as regulation, improved ship design and technology, and risk management advances.”

Even so, that’s a startling rate of one major ship lost almost every week. Most of them don’t make the news. Though classified as “major,” most of these ships are far smaller than the Ever Given or the Felicity Ace. Their crews also largely comprise seafarers from countries like the Philippines or India, the ships sink far away (the biggest portion of losses is around the South China Sea), and their cargo isn’t something that Americans consumers miss. But when ships laden with things Americans care about, such as cars and cookbooks, start hitting choppy seas, they tune in.

In 2015, the cargo ship El Faro sank in the Atlantic Ocean with American sailors on board—a rare loss from the shrinking U.S.-flagged fleet. The Ever Given snarled Suez Canal traffic headed to Europe, affecting Western consumers and becoming a somewhat blunt metaphor for supply-chain disruptions affecting all kinds of goods. The Felicity Ace was bound for Rhode Island when it caught fire, carrying luxury cars for the U.S. market. One Porsche on board was being shipped to the editor of a popular car-review site .

Even under these circumstances, a major disaster doesn’t always make much national news. In September 2019, a car carrier called the Golden Ray, roughly the same size as the Felicity Ace, capsized in St. Simons Sound off Georgia. No cargo ship so large had sunk in U.S. coastal waters since the Exxon Valdez, and the process of breaking up the ship—one of the most expensive salvage efforts in history—concluded only in October. Outside of the trade and regional press, however, the story barely made a splash.

The pandemic could be a factor in some of these recent accidents. Every link in the supply chain, from truckers to ports to shipboard crews, is subject to strain and fatigue. When the freighter Wakashio grounded off Mauritius in 2020, two crew members had been on board for more than a year, prevented from normal rotations onto shore and trips home because of quarantine rules.

Derek Thompson: America is running out of everything

But two problems do seem to be growing: shipboard fires and containers going overboard, like the ones that sent the cookbooks to a watery grave. The reasons have nothing to do with the pandemic. First, the size of vessels continues to grow, though the crews in charge of wrangling them stay the same size. The Ever Given was one of the largest ships in the world when it launched, at 20,000 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs), a benchmark for container ships. One factor in its grounding was that the huge wall of boxes on board effectively acted as a sail, allowing the wind to drive the ship into the canal’s bank. But ships as large as 24,000 TEUs will soon join the fleet.

“Vessel size has a direct correlation to the potential size of loss,” Allianz notes. “Car transporters/RoRo and large container vessels are at higher risk of fire with the potential for greater consequences should one break out.”

Second, ships are also at greater risk of losing containers, or even sinking, when they hit unexpected storms. Climate change means that rather than being confined to specific seasons, storms can hit at any time. “The weather is getting more unpredictable, and these ships are getting bigger, so they’re stacking higher,” Konrad said. “When the ships get hit in a wave, you get a bigger lever that’s pulling the containers over.” (In a bitter environmental irony, the Felicity Ace fire has kept burning because of lithium-ion batteries on electric cars .) In other words, the recent rash of high-profile shipping snafus may be only a factor of greater attention—but a warming planet means a mounting number of disasters might be just over the horizon.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Ship carrying thousands of luxury cars sinks in the Atlantic after burning for weeks

Jonathan Franklin

Smoke billows from the burning Felicity Ace car-transport ship as seen from a Portuguese navy vessel southeast of the mid-Atlantic Portuguese Azores islands. The large cargo vessel carrying cars from Germany to the U.S. sank in the mid-Atlantic 13 days after a fire broke out on board. Portuguese navy via AP hide caption

Smoke billows from the burning Felicity Ace car-transport ship as seen from a Portuguese navy vessel southeast of the mid-Atlantic Portuguese Azores islands. The large cargo vessel carrying cars from Germany to the U.S. sank in the mid-Atlantic 13 days after a fire broke out on board.

A large cargo ship that was carrying luxury cars from Germany to the U.S. sank Tuesday in the mid-Atlantic — nearly two weeks after a fire broke out on board, according to Portuguese navy officials.

Officials confirmed that the ship, Felicity Ace, lost stability and sank about 250 miles off Portugal's Azores islands as it was being towed to land. The ship sank in a location outside Portugal's economic zone in an area that's nearly 2 miles deep.

Navio mercante "Felicity Ace" afunda fora da Zona Económica e Exclusiva Portuguesa Hoje, durante o reboque, que se tinha iniciado no dia 24 de fevereiro, o navio "Felicity Ace" perdeu estabilidade tendo vindo a afundar-se. Notícia completa em https://t.co/dxKBKcyN2o pic.twitter.com/yZygL537uk — Marinha (@MarinhaPT) March 1, 2022

In its statement, the Portuguese navy said that only a few pieces of debris and a small amount of oil were visible where the ship sank and that tugboats were breaking up the patch of oil with hoses.

One of the vessels that had been monitoring the Felicity Ace was en route to Ponta Delgada in the Azores to pick up pollution containment equipment, Portuguese navy officials said.

The 650-foot-long vessel is capable of carrying 4,000 cars. It is unclear how many vehicles were on board the ship.

European auto manufacturers declined to comment regarding exactly how many cars and what models were on board the ship, The Associated Press reported . However, Porsche customers in the U.S. were being contacted individually by their dealership.

A burning cargo ship full of Porsches and VWs is adrift in the mid-Atlantic

"We are already working to replace every car affected by this incident and the first new cars will be built soon," Angus Fitton, vice president of public relations at Porsche Cars North America Inc., told the AP.

The Portuguese navy rescued all 22 members of the crew from the ship, which was scheduled to arrive in Davisville, R.I., on Feb. 16. The crew was taken by helicopter to Faial island in the Azores, the AP reported. None of the crew members was hurt.

Volkswagen confirmed to The Wall Street Journal that insurance has covered the loss of its vehicles, which could be at least $155 million , insurance experts told the Journal . The total estimated loss for all the cargo, which included Porsches, Bentleys, Lamborghinis and Volkswagens, is close to $440 million, the Journal reported.

- Mid-Atlantic

- Updated Terms of Use

- New Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Closed Caption Policy

- Accessibility Statement

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. ©2024 FOX News Network, LLC. All rights reserved. Quotes displayed in real-time or delayed by at least 15 minutes. Market data provided by Factset . Powered and implemented by FactSet Digital Solutions . Legal Statement . Mutual Fund and ETF data provided by Refinitiv Lipper .

Billionaire's luxury superyacht slips from cargo ship, gets lost at sea

Fox News Flash top headlines for June 1

Fox News Flash top headlines for June 1 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

The billionaire owner of a 130-foot yacht , named MY Song, is singing the blues after his vessel got lost at sea when it fell off a cargo ship.

The $38 million superyacht, which was on the last leg of a journey that began in the Caribbean, was not secured correctly by the crew, according to the company that transported her , when it fell overboard last Saturday.

The owner is Italian billionaire Pier Luigi Loro Piana, who is heir to a luxury clothing company. Forbes magazine puts his net worth at $1.6 billion.

"For anyone who loves the sea, his boat is like a second home, and it is as if my home has burnt down," Piana, 67, told Italian newspaper La Repubblica.

ANOTHER ITALIAN VILLAGE IS SELLING HOMES FOR LESS THAN $2

MY Song, which was built in 2016, was being transported to Ibiza to take part in the Logo Piana Superyacht Regatta, which is running in Porto Cervo from June 3 to June 6, when it broke loose over the weekend. (Baltic Yachts)

MY Song, which was built in 2016, was being transported to Ibiza to take part in the Logo Piana Superyacht Regatta, which is running in Porto Cervo from June 3 to June 6, when it broke loose over the weekend. MY Song won last year.

The yacht has since been located, with salvagers now working to prepare her for tow.

The head of Peters & May, the company that handles MY Song’s transporting, said in a statement to the press: “Upon receipt of the news Peters & May instructed the captain of the MV Brattinsborg to attempt salvage whilst 3rd party salvors were appointed."

LUXURY YACHT TESTER NEEDED FOR $93G DREAM JOB

“The vessel maintained visual contact with My Song until the air and sea search was initiated. As of 0900hr BST on 28th May 2019 the salvage attempts are still ongoing,” David Holley said.

On social media, yachting organizations and publications lamented the misfortune that befell MY Song, a star in the regatta and luxury yacht worlds. Its past honors include Best Yacht at the World Superyacht Awards. (Baltic Yachts)

“A full investigation into the cause of the incident has been launched,” he continued. “However the primary assessment is that the yacht’s cradle (owned and provided by the yacht, warrantied by the yacht for sea transport and assembled by the yacht’s crew) collapsed during the voyage from Palma to Genoa and subsequently resulted in the loss of MY Song overboard. I will add that this is the initial assessment and is subject to confirmation in due course.”

On social media, yachting organizations and publications lamented the misfortune that befell MY Song, a star in the regatta and luxury yacht worlds. Its past honors include Best Yacht at the World Superyacht Awards.

CEO and co-chairman of Italian fashion group Loro Piana, Pier Luigi Loro Piana, poses in Quarona on September 8, 2013. AFP PHOTO / GIUSEPPE CACACE (Photo credit should read GIUSEPPE CACACE/AFP/Getty Images)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

GCaptain.com noted that besides being an award-winning performer in competitions, MY Song was a jewel in luxuriating circles: “The interior accommodation is for six to eight guests including the owner, the focal point being a spectacular deck saloon with hull and superstructure ports, plus skylights providing panoramic outboard views.”

Fox News' "Antisemitism Exposed" newsletter brings you stories on the rising anti-Jewish prejudice across the U.S. and the world.

You've successfully subscribed to this newsletter!

- Transportation & Logistics ›

Water Transport

- Worldwide ship losses by vessel type 2013-2022

Number of ship losses worldwide between 2013 and 2022, by vessel type

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

2013 to 2022

Other statistics on the topic Water transportation industry

- Number of merchant ships by type 2022

- Number of pirate attacks worldwide 2010-2022

- Largest shipbuilding nations based on gross tonnage 2022

- Largest container ports worldwide based on throughput 2022

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Statistics on " Ocean shipping worldwide "

- Transport volume of worldwide maritime trade 1990-2021

- Loaded and unloaded tonnage in worldwide maritime trade 2021, by continent

- Containerized cargo flows 2022, by trade route

- YoY change in world container port throughput 2014-2027

- Number of port arrivals worldwide by country 2022

- Median time spent in port by container ships worldwide by segment 2021

- Carrying capacity of the world merchant fleet 2013-2021

- Global merchant fleet by type - capacity 2022

- Capacity of oil tankers in seaborne trade 1980-2022

- Capacity of container ships in seaborne trade 1980-2023

- Capacity of general cargo vessels in seaborne trade 1980-2022

- Tanker freight in international maritime trade 1970-2021

- Dry cargo in international maritime trade 1970-2021

- Main bulk cargo in international maritime trade 1970-2021

- Leading ocean freight forwarders worldwide based on TEUs 2022

- Kuehne + Nagel 's worldwide revenue 2006-2023

- Leading container ship operators based on total TEUs 2024

- AP Møller - Mærsk's revenue A/S 2009-2023

- Shanghai International Port's revenue FY 2011-2022

- Major marine terminal operators worldwide based on throughput 2021

- PSA International - revenue 2009-2022

- Global shipbuilding order book 2022, by vessel type

- Number of orderbook ships of the leading container ship operators 2024

- Container ship operators based on TEU capacity of ships in order book 2023

- Number of commercial vessels dismantled worldwide 2013-2022

- Number of commercial vessels scrapped worldwide by country 2022

- Causes of ship losses worldwide by type 2022

- Number of pirate attacks worldwide by ship type 2022

- Number of pirate attacks worldwide by nationality of shipper 2022

- Number of crew members attacked by maritime pirates 2015-2022

Other statistics that may interest you Ocean shipping worldwide

- Premium Statistic Transport volume of worldwide maritime trade 1990-2021

- Premium Statistic Loaded and unloaded tonnage in worldwide maritime trade 2021, by continent

- Basic Statistic Containerized cargo flows 2022, by trade route

- Premium Statistic Largest container ports worldwide based on throughput 2022

- Premium Statistic YoY change in world container port throughput 2014-2027

- Premium Statistic Number of port arrivals worldwide by country 2022

- Premium Statistic Median time spent in port by container ships worldwide by segment 2021

- Premium Statistic Carrying capacity of the world merchant fleet 2013-2021

- Premium Statistic Number of merchant ships by type 2022

- Premium Statistic Global merchant fleet by type - capacity 2022

- Premium Statistic Capacity of oil tankers in seaborne trade 1980-2022

- Premium Statistic Capacity of container ships in seaborne trade 1980-2023

- Basic Statistic Capacity of general cargo vessels in seaborne trade 1980-2022

- Premium Statistic Tanker freight in international maritime trade 1970-2021

- Premium Statistic Dry cargo in international maritime trade 1970-2021

- Premium Statistic Main bulk cargo in international maritime trade 1970-2021

- Premium Statistic Leading ocean freight forwarders worldwide based on TEUs 2022

- Basic Statistic Kuehne + Nagel 's worldwide revenue 2006-2023

- Premium Statistic Leading container ship operators based on total TEUs 2024

- Premium Statistic AP Møller - Mærsk's revenue A/S 2009-2023

- Premium Statistic Shanghai International Port's revenue FY 2011-2022

- Premium Statistic Major marine terminal operators worldwide based on throughput 2021

- Premium Statistic PSA International - revenue 2009-2022

Shipbuilding & shipbreaking

- Premium Statistic Largest shipbuilding nations based on gross tonnage 2022

- Premium Statistic Global shipbuilding order book 2022, by vessel type

- Premium Statistic Number of orderbook ships of the leading container ship operators 2024

- Premium Statistic Container ship operators based on TEU capacity of ships in order book 2023

- Premium Statistic Number of commercial vessels dismantled worldwide 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of commercial vessels scrapped worldwide by country 2022

Accidents & casualties

- Basic Statistic Causes of ship losses worldwide by type 2022

- Basic Statistic Worldwide ship losses by vessel type 2013-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of pirate attacks worldwide 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of pirate attacks worldwide by ship type 2022

- Premium Statistic Number of pirate attacks worldwide by nationality of shipper 2022

- Premium Statistic Number of crew members attacked by maritime pirates 2015-2022

Further related statistics

- Basic Statistic Shipping accidents worldwide - victim numbers 2000-2014

- Premium Statistic Number of missing persons in marine accidents in Japan 2012-2021

- Premium Statistic Casualties of marine ship repairing and ship accidents within Hong Kong 2020, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of marine accident injuries in Japan 2012-2021

- Premium Statistic Casualties of marine construction within Hong Kong 2020, by type

- Premium Statistic Casualties of marine cargo handling accidents within Hong Kong waters 2020, by type

- Basic Statistic Ship losses by vessel type - worldwide 2020

- Premium Statistic Breakdown of marine insurance claim value worldwide by cause 2013-2018

- Premium Statistic Breakdown of marine insurance claims worldwide by cause 2013-2018

- Premium Statistic World's merchant fleet - number of passenger ships 2017

- Premium Statistic NATO countries - merchant ships 2014

- Premium Statistic Global container ship fleet: size by flag the ship is flying 2013

- Premium Statistic U.S. foreign waterborne commerce in ton-miles 1997-2016

- Premium Statistic World container ship fleet - volume 2013

- Premium Statistic Passenger capacity of ships worldwide

- Premium Statistic Number of fatalities in marine accidents in Japan 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of incidents attended by the coastguard in the United Kingdom (UK) 2004-2014

- Premium Statistic Number of bulk carrier losses worldwide 2011-2020, by reported cause

- Premium Statistic Wreck removal costs - by vessel 2002-2012

Further Content: You might find this interesting as well

- Shipping accidents worldwide - victim numbers 2000-2014

- Number of missing persons in marine accidents in Japan 2012-2021

- Casualties of marine ship repairing and ship accidents within Hong Kong 2020, by type

- Number of marine accident injuries in Japan 2012-2021

- Casualties of marine construction within Hong Kong 2020, by type

- Casualties of marine cargo handling accidents within Hong Kong waters 2020, by type

- Ship losses by vessel type - worldwide 2020

- Breakdown of marine insurance claim value worldwide by cause 2013-2018

- Breakdown of marine insurance claims worldwide by cause 2013-2018

- World's merchant fleet - number of passenger ships 2017

- NATO countries - merchant ships 2014

- Global container ship fleet: size by flag the ship is flying 2013

- U.S. foreign waterborne commerce in ton-miles 1997-2016

- World container ship fleet - volume 2013

- Passenger capacity of ships worldwide

- Number of fatalities in marine accidents in Japan 2013-2022

- Number of incidents attended by the coastguard in the United Kingdom (UK) 2004-2014

- Number of bulk carrier losses worldwide 2011-2020, by reported cause

- Wreck removal costs - by vessel 2002-2012

Search and Rescue How To Find A Missing Boat

Oct 24, 2019 | News

Portrait of an Inessential Government Worker

Glory isn’t part of the deal when you go to work for the federal government., “i’ve only thought about one problem in my life ,” says art allen. “which is how to improve coast guard search and rescue.”.

Art Allen – Improving Coast Guard Search & Rescue Photographer: Annie Tritt/Bloomberg

October 15, 2019, Updated on October 21, 2019 The following is adapted from a new chapter for the paperback edition of “The Fifth Risk,” which will be published by Norton in November.

I found Art Allen standing on the lawn just outside his front door, a few miles inland from some uninviting Connecticut beach. He was in his mid-60s, and a scientist — but a scientist with a man-of-action feel to him. He wore a Coast Guard Search and Rescue polo and a massive Fenix 3 GPS watch, and he had this snow-white Hemingway beard. Six canoes hung from hooks inside his garage, a scrum of mountain bikes leaned against the wall, and all looked as if they had a lot of miles on them. So did he.

For nearly 40 years, Art Allen had been the lone oceanographer inside the U.S. Coast Guard’s Search and Rescue division. Among other subjects, he had mastered the art of finding things and people lost at sea. At any given moment, all sorts of objects are drifting in the ocean, a surprising number of them Americans. The Coast Guard plucks 10 people a day out of the ocean, on average. Another three die before they’re found. Which is to say that 13 Americans, every day, need to be hauled out of the water or off some crippled sailboat or sea kayak or paddleboard. “I’ve only thought about one problem in my life,” said Art, with an odd little laugh, which sounded half like a chuckle and half like an apology for speaking up. “Which is how to improve Coast Guard search and rescue.”

I’d first learned of Art’s existence back in early 2019, during the 35-day government shutdown. About half the employees of the federal government had been deemed essential for the safety of life and property and been made to work without pay. The other half had been sent home. The line running between the two groups, the essential and the inessential, was oddly drawn. The airport people who make sure that the toiletries in your carry-on can’t be turned into a bomb were required to show up for work. The Federal Bureau of Investigation agents working undercover inside terrorist groups were told to go home. So were the Food and Drug Administration’s food safety inspectors; the people at the Environmental Protection Agency assigned to stop poison from leaking from power plants; and the hundreds of immigration court judges who would decide the fate of thousands of immigrants held in detention facilities.

During the shutdown I’d stumbled upon a very long list of federal workers who had been nominated for an obscure public-service award called the Sammies . Virtually all the people on the list had been laid off without pay and more or less told by their society that their work was not all that important. I wondered what it felt like to be at once up for an award for one’s work, and required by law not to do it. The list was in alphabetical order. At the top was Arthur A. Allen.

Art hadn’t set out in life to save people at sea; he hadn’t actually set out to do anything in particular except to be a scientist. “I think I was always going to be a scientist,” he said. “Science is driven by the love of the subject. I have an aunt who studies the genetics of mushrooms. I don’t know why she finds mushroom genetics beautiful and fascinating, but she does.” What Art had always found beautiful and fascinating was water. He’d grown up on the New York side of Lake Champlain, and even as a little kid his idea of fun was to dig tunnels to drain snow ponds. He went to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and designed his own major, aquatic science and engineering. From there, he went into a graduate program in physical oceanography at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. “Oceanographers come in two flavors,” he said, with the same odd little apology-chuckle. “To find out which one you are, they send you to sea for a couple of weeks. And you either become a theoretical oceanographer — because you throw up a lot. Or you become a field guy. And I was particularly gifted with a strong stomach .”

Book about a Mexican fisherman who survived for 438 days alone on a raft at sea Photographer: Annie Tritt/Bloomberg

He was also particularly gifted at finding things out. “That was one of my strengths,” he said, but without his odd little laugh. “I could get good data out of the sea.”

The question at the start of Art’s career, back in 1984, was where to apply that strength. He’d seen an ad placed by the Coast Guard for a junior researcher, and while the idea of government work wasn’t as off-putting in the early 1980s as it would become in, say, 2019, Art didn’t really think of himself as a government guy. He certainly didn’t have any sense of being on some mission. “I thought I’d give it six months,” he said.

Just then the Coast Guard was trying to figure out how to improve its ability to spot objects on the ocean surface from its planes and helicopters. It was a little shocking how hard it was to see even a small boat from 1,000 feet; if you flew over and didn’t see it, you might never look there again. To see better, there wasn’t much the Coast Guard wasn’t willing to try. Not long before Art arrived, for instance, it’d attempted to train pigeons, riding in cages attached to Coast Guard aircraft, to respond to any orange object in the ocean by pecking at an alarm. The pigeons seemed to have natural advantages over humans as spotters of objects lost at sea. Their vision was sharper, and they never got bored or distracted. The pigeons didn’t miss a thing, which turned out to be their downfall. “The problem was that there are orange things that aren’t survivors and things not wearing orange that are survivors,” said Art. “The pigeons drove the pilots crazy.”

By the time Art arrived, the pigeons were gone, replaced by questions that Art did his best to answer. For example, the Coast Guard wanted to know the odds of a plane flying at 500 feet over some object actually spotting that object, so Art threw stuff in the water and made people fly over it and try to see it. The Coast Guard wanted him to find better ways to measure ocean currents and winds, so Art built and bought better gadgets to measure them. The Coast Guard needed a device that might better track what was happening to currents at the last known position of some boat or person. Art helped invent a new buoy to do the job.

When a Coast Guard commander looking for a guy lost at sea, and presumed to be floating on a life raft made by the Elliot company, realized that he didn’t really know what an Elliot life raft looked like, or how fast it might travel in relation to the wind compared to life rafts better known to the Coast Guard, he called Art and asked him — and Art called a facility in Essex, Connecticut, that certified life rafts and had them send him a brochure for one. “I’m just looking at it as a pure scientist,” said Art. “They want to know how these objects drift in the ocean, so I figure out how they drift in the ocean.”

In June 2002, off the southern shore of Long Island, a fishing boat was swamped in a storm and threw the four men on it into 60-degree waters. The men had been competing in a shark-fishing tournament when the storm came through. There were a couple of Mustang survival suits on the boat — not enough for all the men. Before they’d capsized, the men had sent a distress signal that was picked up by a Coast Guard station in New Jersey, but the signal was fuzzy and the Coast Guard had no idea where the men were or even, really, if they were in trouble. The real search didn’t get going until that night, when the boat failed to return to port. It lasted four days.

A human can survive in cold water for maybe 36 hours, even inside a Mustang suit, but the Mustang suit company told the men’s families that anyone wearing the suit could last for eight days. The families implored the Coast Guard to keep looking long past the point the Coast Guard thought there was any point in doing so. Three of the men were never found. The body of the fourth was discovered a week later by a fishing boat 30 miles off the New Jersey coast.

When it was over, the people who had failed to find the men called Art with a question: Who’s right, us or the Mustang company? Art looked into the hypothermia models used by the Coast Guard and found they had some problems, apart from the issues raised by the suit. The service made no allowance for the clothing a person might be wearing under the suit, for instance, or his body fat. It assumed the weather was constant throughout the search and that nights in the water were the same as days in the water. “This was another area of Coast Guard ignorance,” said Art. “Survivability.”

Art sought out scientists who had studied hypothermia, and collected what was known on the subject. Even if they’d been wearing the Mustang suits, he concluded, the men almost certainly would have died within two days. These studies suggested to Art that the old Coast Guard models had been, if anything, optimistic about the ability of human beings floating in ocean water to survive. Never mind hypothermia. A person could go only three days without water and 62 hours without sleep before he lost the ability to keep himself alive. But what really struck Art Allen about the whole incident was that “no one really knew.” No one knew how a Mustang suit, or anything else you might be wearing, might affect your ability to survive. Not even the scientists who studied hypothermia.

Art had started his career as a junior researcher, but a decade into it he was the lone oceanographer inside Coast Guard Search and Rescue. And he began to notice something: The people engaged in rescuing Americans at sea were turning to him for answers to questions he’d never been asked. The questions put to him weren’t questions to which he should obviously know the answer. “It occurred to me,” said Art, “that I was getting these questions. And I realize that if I don’t know the answers, no one does.”

People were coming to him because they had nowhere else to go. “Rather than being the wide-eyed scientist in the background, suddenly I’m being asked for my opinions,” said Art. “It was like they thought, There’s this bearded oceanographer guy out there; maybe he knows.” Usually he didn’t know, but he had his talent for creating knowledge.

The biggest thing that no one knew, he decided, was how various objects drifted at sea. The ocean never stopped moving. Every object was pulled and pushed along by currents and winds. And so if you wanted to know where an object might be that had been spotted, say, five hours ago 20 miles due east of Cape Hatteras, you needed to know the winds and the currents off Cape Hatteras in the intervening five hours.

But that knowledge wasn’t enough: You also needed to know exactly what the object was and how it interacted with the forces of nature. Leeway was the technical term for the difference between the movement of an object and the current that pulled it along. “The Coast Guard has always been interested in physical oceanography — oil spills and icebergs,” said Art. “You got stuff that gets into the water and you want to predict where it’s going to go.” Even if they started in the same place, a disabled fishing trawler and a sea kayak might soon be many miles apart.

Art Allen set out to find what was known on the subject. Shockingly little, it turned out. The history of search and rescue at sea is mostly the story of people neither being searched for nor being rescued. For most of human history, lost at sea meant gone for good.

“It really only started during World War II,” said Art. “There was not much looking for people at sea until we started losing pilots in the Pacific.” Scouring the literature, he found that there was really only one good study of leeway. A Coast Guard commander named W.E. Chapline, who had been stationed in Hawaii in the late 1950s, had grown sufficiently weary of not finding people that he had made tests on the few objects on which people lost in the South Pacific tended to float: a surfboard, a sampan, a small fishing boat.

“Estimating the Drift of Distressed Small Craft” was published in 1960, in the Coast Guard Alumni Association Bulletin. It was 2 1/2 pages long and wholly original and, like a lot of things wholly original, had its limitations, which the author hinted at. “It was difficult at times to obtain sufficient volunteers from among the local small boat owners,” he wrote, “due mainly to the discomfort involved while drifting, the relatively small size of the local Coast Guard Auxiliary, and generally small number of boats available in Hawaii.