Members: Sign in Here --> Members: Sign in Here Contact Us

Email This Page to a Friend Preview: What About a Sailboat’s Displacement? Doug Hylan Discusses Light and Heavy

April 5, 2013

A mong the dockside pundits, the discussion of light vs. heavy displacement usually revolves around the ability of a cruising sailboat to carry the necessary provisions and gear for extended cruising. I would like to consider the question from another angle: appearance and cost.

L ight displacement boats have some real advantages. Up to a certain point, lighter displacement saves money, both in initial cost and continuing expenses. Cy Hamlin pioneered this idea with his Controversy yachts produced at Mt. Desert Yacht Yard in the 1960s. Many people are surprised to learn that boats, like meat, tend to cost by the pound, not the foot. Compared to a heavy displacement 40-foot sailboat, a lighter boat of the same length will require smaller sails, lighter rigging, smaller ground tackle, a smaller engine, and less ballast.

U nder many conditions, lighter boats can also be faster. For one thing, they can cheat the devil of hull speed, even plane if they are very light and have the proper hull shape. This was one reason that MARY ANN, the first Barnegat Bay A Cat, was able to sweep aside the older heavier competition on the bay, even though they sported vastly bigger sail plans.

N at Herreshoff, the Wizard of Bristol, took advantage of both of these factors. One of the many facets of his wizardliness was his intuitive feel for light, stiff and strong construction. His boats generally had lighter structure than the competition, making them both cheaper to build and faster under sail. Even when a rating rule demanded that boats be of a certain displacement, lighter construction meant that more of that weight could be put into ballast. Ballast is not only one of the cheapest components per pound in a boat, but a greater proportion of ballast increases stability, meaning that the boat can stand up to more wind before reefing.

A esthetics, however, is one area where lighter boats have trouble competing. While they may not be able to enumerate the reasons, most people will admit that older boats tend to look more graceful and appealing than their modern sisters. Although several factors are involved, a major one is freeboard, or the amount of hull that shows above the waterline. Older boats generally have less, and just as with cars, lower and sleeker usually looks better.

I n the world of boat design numbers (called hydrostatics), the relative “lightness” or “heaviness” of a boat is defined by its displacement/length ratio, usually abbreviated as D/L. I’ll spare you the formula, but keep in mind that this is a dimensionless number – in other words, it makes no difference if the boat is a dinghy or an ocean liner. If her D/L is 400 she is considered to be in the heavy displacement realm. If the D/L is 150, she is pretty light.

W hy do lighter boats tend to be higher sided? Archimedes who purportedly jumped out of his tub and ran naked through the streets of ancient Syracuse shouting “Eureka!” is credited with the answer. The heavier a boat is, the more there is of it under water. The more there is under water, the less of it there needs to be above water to get the same amount of headroom.

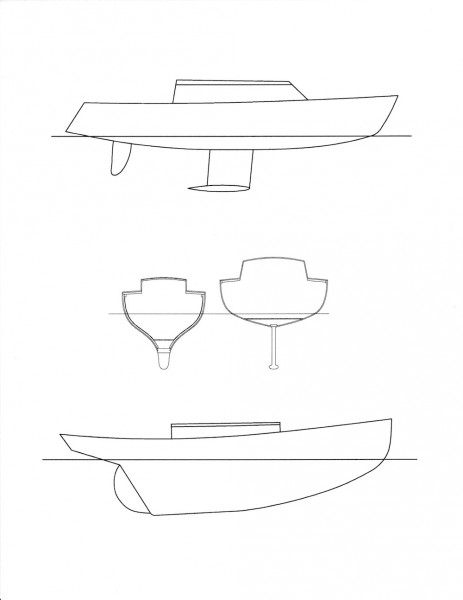

C onsider the two boats shown below, one an old style heavy cruiser (D/L 400), the other a modern light displacement sister (D/L 150). Both boats have an overall length of 33′, a waterline length of 28 feet and a draft of 5 1/2 feet. They both have the same 6-foot headroom, but the cabin sole of the lighter boat must be much higher, so either the topsides or the cabin (usually both) has to be moved up to get the same headroom.

S o, tall people who are unwilling to bump their heads (or bend over to avoid it) can be the ruination of good looks in small, light displacement boats. Daysailers, where headroom is not considered essential, are generally immune to this problem, and once a yacht gets to 60 or so feet in length, there is plenty of height in either type for homo erects.

. . . sign up to the right to get immediate access to this full post, plus you'll get 10 of our best videos for free.

Get Free Videos & Learn More Join Now!! for Full Access Members Sign In

GET THIS FULL POST!

Get Immediate Access, Plus 10 of Our Best Videos

- Email Address

My Cruiser Life Magazine

Basics of Sailboat Hull Design – EXPLAINED For Owners

There are a lot of different sailboats in the world. In fact, they’ve been making sailboats for thousands of years. And over that time, mankind and naval architects (okay, mostly the naval architects!) have learned a thing or two.

If you’re wondering what makes one sailboat different from another, consider this article a primer. It certainly doesn’t contain everything you’d need to know to build a sailboat, but it gives the novice boater some ideas of what goes on behind the curtain. It will also provide some tips to help you compare different boats on the water, and hopefully, it will guide you towards the sort of boat you could call home one day.

Table of Contents

Displacement hulls, semi displacement hulls, planing hulls, history of sailboat hull design, greater waterline length, distinctive hull shape and fin keel designs, ratios in hull design, the hull truth and nothing but the truth, sail boat hull design faqs.

Basics of Hull Design

When you think about a sailboat hull and how it is built, you might start thinking about the shape of a keel. This has certainly spurred a lot of different designs over the years, but the hull of a sailboat today is designed almost independently of the keel.

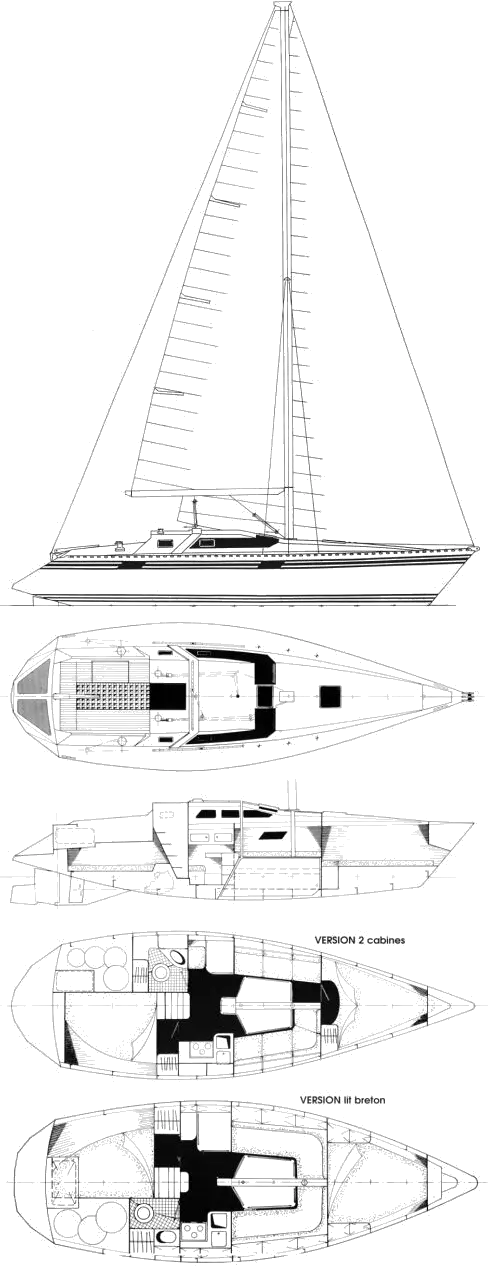

In fact, if you look at a particular make and model of sailboat, you’ll notice that the makers often offer it with a variety of keel options. For example, this new Jeanneau Sun Odyssey comes with either a full fin bulb keel, shallow draft bulb fin, or very shallow draft swing keel. Where older long keel designs had the keel included in the hull mold, today’s bolt-on fin keel designs allow the manufacturers more leeway in customizing a yacht to your specifications.

What you’re left with is a hull, and boat hulls take three basic forms.

- Displacement hull

- Semi-displacement hulls

- Planing hulls

Most times, the hull of a sailboat will be a displacement hull. To float, a boat must displace a volume of water equal in weight to that of the yacht. This is Archimedes Principle , and it’s how displacement hulled boats get their name.

The displacement hull sailboat has dominated the Maritimes for thousands of years. It has only been in the last century that other designs have caught on, thanks to advances in engine technologies. In short, sailboats and sail-powered ships are nearly always displacement cruisers because they lack the power to do anything else.

A displacement hull rides low in the water and continuously displaces its weight in water. That means that all of that water must be pushed out of the vessel’s way, and this creates some operating limitations. As it pushes the water, water is built up ahead of the boat in a bow wave. This wave creates a trough along the side of the boat, and the wave goes up again at the stern. The distance between the two waves is a limiting factor because the wave trough between them creates a suction.

This suction pulls the boat down and creates drag as the vessel moves through the water. So in effect, no matter how much power is applied to a displacement hulled vessel, it cannot go faster than a certain speed. That speed is referred to as the hull speed, and it’s a factor of a boat’s length and width.

For an average 38 foot sailboat, the hull speed is around 8.3 knots. This is why shipping companies competed to have the fastest ship for many years by building larger and larger ships.

While they might sound old-school and boring, displacement hulls are very efficient because they require very little power—and therefore very little fuel—to get them up to hull speed. This is one reason enormous container ships operate so efficiently.

Of course, living in the 21st century, you undoubtedly have seen boats go faster than their hull speed. Going faster is simply a matter of defeating the bow wave in one way or another.

One way is to build the boat so that it can step up onto and ride the bow wave like a surfer. This is basically what a semi-displacement hull does. With enough power, this type of boat can surf its bow wave, break the suction it creates and beat its displacement hull speed.

With even more power, a boat can leave its bow wave in the dust and zoom past it. This requires the boat’s bottom to channel water away and sit on the surface. Once it is out of the water, any speed is achievable with enough power.

But it takes enormous amounts of power to get a boat on plane, so planing hulls are hardly efficient. But they are fast. Speedboats are planing hulls, so if you require speed, go ahead and research the cost of a speedboat .

The most stable and forgiving planing hull designs have a deep v hull. A very shallow draft, flat bottomed boat can plane too, but it provides an unforgiving and rough ride in any sort of chop.

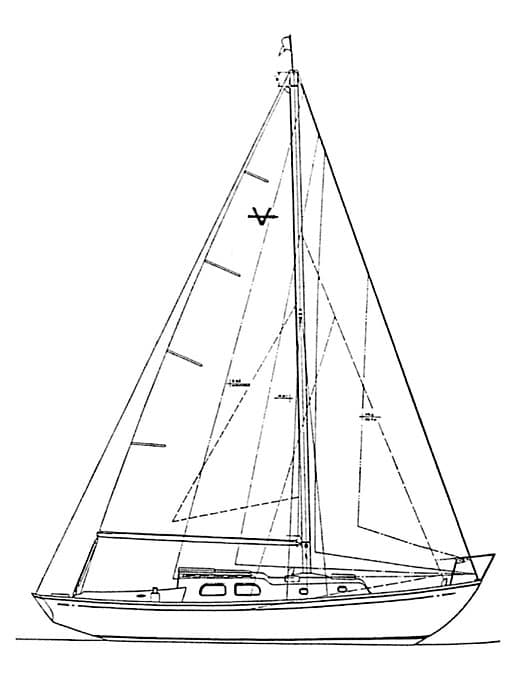

If you compare the shapes of the sailboats of today with the cruising boat designs of the 1960s and 70s, you’ll notice that quite a lot has changed in the last 50-plus years. Of course, the old designs are still popular among sailors, but it’s not easy to find a boat like that being built today.

Today’s boats are sleeker. They have wide transoms and flat bottoms. They’re more likely to support fin keels and spade rudders. Rigs have also changed, with the fractional sloop being the preferred setup for most modern production boats.

Why have boats changed so much? And why did boats look so different back then?

One reason was the racing standards of the day. Boats in the 1960s were built to the IOR (International Offshore Rule). Since many owners raced their boats, the IOR handicaps standardized things to make fair play between different makes and models on the racecourse.

The IOR rule book was dense and complicated. But as manufacturers started building yachts, or as they looked at the competition and tried to do better, they all took a basic form. The IOR rule wasn’t the only one around . There were also the Universal Rule, International Rule, Yacht Racing Association Rul, Bermuda Rule, and a slew of others.

Part of this similarity was the rule, and part of it was simply the collective knowledge and tradition of yacht building. But at that time, there was much less distance between the yachts you could buy from the manufacturers and those setting off on long-distance races.

Today, those wishing to compete in serious racing a building boat’s purpose-built for the task. As a result, one-design racing is now more popular. And similarly, pleasure boats designed for leisurely coastal and offshore hops are likewise built for the task at hand. No longer are the lines blurred between the two, and no longer are one set of sailors “making do” with the requirements set by the other set.

Modern Features of Sailboat Hull Design

So, what exactly sets today’s cruising and liveaboard boats apart from those built-in decades past?

Today’s designs usually feature plumb bows and the maximum beam carried to the aft end. The broad transom allows for a walk-through swim platform and sometimes even storage for the dinghy in a “garage.”

The other significant advantage of this layout is that it maximizes waterline length, which makes a faster boat. Unfortunately, while the boats of yesteryear might have had lovely graceful overhangs, their waterline lengths are generally no match for newer boats.

The wide beam carried aft also provides an enormous amount of living space. The surface area of modern cockpits is nothing short of astounding when it comes to living and entertaining.

If you look at the hull lines or can catch a glimpse of these boats out of the water, you’ll notice their underwater profiles are radically different too. It’s hard to find a full keel design boat today. Instead, fin keels dominate, along with high aspect ratio spade rudders.

The flat bottom boats of today mean a more stable boat that rides flatter. These boats can really move without heeling over like past designs. Additionally, their designs make it possible in some cases for these boats to surf their bow waves, meaning that with enough power, they can easily achieve and sometimes exceed—at least for short bursts—their hull speeds. Many of these features have been found on race boats for decades.

There are downsides to these designs, of course. The flat bottom boats often tend to pound when sailing upwind , but most sailors like the extra speed when heading downwind.

How Do You Make a Stable Hull

Ultimately, the job of a sailboat hull is to keep the boat afloat and create stability. These are the fundamentals of a seaworthy vessel.

There are two types of stability that a design addresses . The first is the initial stability, which is how resistant to heeling the design is. For example, compare a classic, narrow-beamed monohull and a wide catamaran for a moment. The monohull has very little initial stability because it heels over in even light winds. That doesn’t mean it tips over, but it is relatively easy to make heel.

A catamaran, on the other hand, has very high initial stability. It resists the heel and remains level. Designers call this type of stability form stability.

There is also secondary stability, or ultimate stability. This is how resistant the boat is to a total capsize. Monohull sailboats have an immense amount of ballast low in their keels, which means they have very high ultimate stability. A narrow monohull has low form stability but very high ultimate stability. A sailor would likely describe this boat as “tender,” but they would never doubt its ability to right itself after a knock-down or capsize.

On the other hand, the catamaran has extremely high form stability, but once the boat heels, it has little ultimate stability. In other words, beyond a certain point, there is nothing to prevent it from capsizing.

Both catamarans and modern monohulls’ hull shapes use their beams to reduce the amount of ballast and weight . A lighter boat can sail fast, but to make it more stable, naval architects increase the beam to increase the form stability.

If you’d like to know more about how stable a hull is, you’ll want to learn about the Gz Curve , which is the mathematical calculation you can make based on a hull’s form and ultimate stabilities.

How does a lowly sailor make heads or tails out of this? You don’t have to be a naval architect when comparing different designs to understand the basics. Two ratios can help you predict how stable a design will be .

The first is the displacement to length ratio . The formula to calculate it is D / (0.01L)^3 , where D is displacement in tons and L is waterline length in feet. But most sailboat specifications, like those found on sailboatdata.com , list the D/L Ratio.

This ratio helps understand how heavy a boat is for its length. Heavier boats must move more water to make way, so a heavy boat is more likely to be slower. But, for the ocean-going cruiser, a heavy boat means a stable boat that requires much force to jostle or toss about. A light displacement boat might pound in a seaway, and a heavy one is likely to provide a softer ride.

The second ratio of interest is the sail area to displacement ratio. To calculate, take SA / (D)^0.67 , where SA is the sail area in square feet and D is displacement in cubic feet. Again, many online sites provide the ratio calculated for specific makes and models.

This ratio tells you how much power a boat has. A lower ratio means that the boat doesn’t have much power to move its weight, while a bigger number means it has more “get up and go.” Of course, if you really want to sail fast, you’d want the boat to have a low displacement/length and a high sail area/displacement.

Multihull Sailboat Hulls

Multihull sailboats are more popular than ever before. While many people quote catamaran speed as their primary interest, the fact is that multihulls have a lot to offer cruising and traveling boaters. These vessels are not limited to coastal cruising, as was once believed. Most sizable cats and trimarans are ocean certified.

Both catamarans and trimaran hull designs allow for fast sailing. Their wide beam allows them to sail flat while having extreme form stability.

Catamarans have two hulls connected by a large bridge deck. The best part for cruisers is that their big surface area is full of living space. The bridge deck usually features large, open cockpits with connecting salons. Wrap around windows let in tons of light and fresh air.

Trimarans are basically monohulls with an outrigger hull on each side. Their designs are generally less spacious than catamarans, but they sail even faster. In addition, the outer hulls eliminate the need for heavy ballast, significantly reducing the wetted area of the hulls.

Boaters and cruising sailors don’t need to be experts in yacht design, but having a rough understanding of the basics can help you pick the right boat. Boat design is a series of compromises, and knowing the ones that designers and builders take will help you understand what the boat is for and how it should be used.

What is the most efficient boat hull design?

The most efficient hull design is the displacement hull. This type of boat sits low in the water and pushes the water out of its way. It is limited to its designed hull speed, a factor of its length. But cruising at hull speed or less requires very little energy and can be done very efficiently.

By way of example, most sailboats have very small engines. A typical 40-foot sailboat has a 50 horsepower motor that burns around one gallon of diesel every hour. In contrast, a 40-foot planing speedboat may have 1,000 horsepower (or more). Its multiple motors would likely be consuming more than 100 gallons per hour (or more). Using these rough numbers, the sailboat achieves about 8 miles per gallon, while the speedboat gets around 2 mpg.

What are sail boat hulls made of?

Nearly all modern sailboats are made of fiberglass.

Traditionally, boats were made of wood, and many traditional vessels still are today. There are also metal boats made of steel or aluminum, but these designs are less common. Metal boats are more common in expedition yachts or those used in high-latitude sailing.

Matt has been boating around Florida for over 25 years in everything from small powerboats to large cruising catamarans. He currently lives aboard a 38-foot Cabo Rico sailboat with his wife Lucy and adventure dog Chelsea. Together, they cruise between winters in The Bahamas and summers in the Chesapeake Bay.

- MarketPlace

- Digital Archives

- Order A Copy

Offshore sailboat choices

Editor’s note: There are many types of hull design, rig configuration and material choices for offshore sailboats. We talked to four voyaging couples and asked them about the pros and cons of the choice they made when they decided on a voyaging boat.

Rich and Cat Ian-Frese Tayana 37 Anna Rich and Cat Ian-Frese left Seattle after an 11-year refit of their Tayana 37 cutter, Anna . They started out heading in the general direction of South America, where they eventually took a right turn and crossed the South Pacific. They have refit, cruised and lived aboard Anna since 2000.

Rich has a background in research engineering and spent many years working on research grants in emerging laser technologies. He has worked as a project director on R&D projects for the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and NASA. Cat spent over 20 years teaching elementary school, including special education.

Ocean Navigator: Why did you decide to voyage in a heavy-displacement boat? Rich and Cat Ian-Frese: My wife and I decided to voyage in a full-keel (with cutaway forefront) heavy-displacement monohull, a Tayana 37 cutter rig, because it has a comfortable and easy motion in the ocean. It feels solid and stable and safe in big waves, even in big confused waves — although the comfort factor is noticeably reduced in big confused waves, as it would be on any vessel in rough seas where the waves are big, short-spaced and coming from multiple directions. This will cause bashing into a headwind and heavy, lumpy rolling dead downwind. In our opinion, a heavier displacement vessel will absorb getting knocked around better than a light-displacement monohull.

ON: What are the advantages and disadvantages of this type of offshore boat? R&CI-F: The advantages of a heavy-displacement monohull, like the Tayana 37 cutter, are a very stable and comfortable ride in normal ocean conditions. The Tayana 37 has modest initial stability for a moderately heavy displacement boat, and it will comfortably heel over initially to dig in and pick up speed and add to its waterline length. And then its secondary stability kicks in, which is effective in keeping you sailing at a comfortable heeling angle. We’ve never felt the heeling angle to be unsafe, even in big rolling seas.

We don’t feel that there is any significant disadvantage to a heavy-displacement boat that is used for ocean voyaging, unless speed is your priority. We’ve never been in a situation where not being able to outrun bad weather resulted in a bad outcome. We think that it would be advantageous at times to attain a knot of speed for every knot of wind, like some fast monohulls and catamarans we know of, but we’re happy to slip along at 4 to 7 knots. It seems less stressful on the boat and rig, and less stressful on the crew as well, especially when conditions deteriorate. Besides, we like being on the ocean and don’t place a lot of emphasis on getting from point A to point B in record-setting time. But that’s just us; we can certainly see how hull speeds of 10 to 20 knots can be appealing when you actually have a chance to get ahead of a forecast bad weather system or have simply just had enough rolling on a 3,000-mile passage.

Many heavy-displacement vessels are full keeled. And while a full-keeled monohull like the Tayana 37 has advantages on the ocean — like righting itself quickly if rolled in heavy seas, and having an easy motion in normal seas, an excellent balance of primary and secondary stability, and a modest turn of speed — there is perhaps a disadvantage in close-quarters work.

In marinas where getting into a Travelift dock or a fuel dock involves backing up in a straight line in windy conditions or in a strong current, maneuverability can be a challenge. We could never back up our Tayana 37 down a narrow fairway and expect to end up exactly where we want to go. It’s not in the nature of the Tayana 37. Bow thrusters are, of course, an option, but we didn’t have thrusters on our boat. Many other boats with long keels, other than the Tayana 37, are simply bad when the transmission is thrown into reverse. Occasionally, we are lucky and the wind and current help us along. But generally the less distance we need to go in reverse, the better. Normal docking and turning in narrow fairways is fine. Just don’t expect consistently perfect results in reverse gear in a heavier breeze or fast-running current with some full-keel boats.

We had a Pearson 30 a long time ago. It had a light displacement and a spade rudder. It could turn on a dime and back down a long narrow fairway in almost any conditions. But there are tradeoffs with any boat. We would never think of taking that vessel on a long ocean voyage with its unprotected rudder. When most of your time is spent on longer passages in unpredictable conditions, a good stable boat that you have complete confidence in when the weather goes south is most important.

ON: For voyagers considering a heavy-displacement sailboat, what advice would you give? R&CI-F: We wouldn’t hesitate to sail a heavy-displacement boat. Personally, we’d feel more secure in conditions that were other than ideal. A heavy-displacement monohull doesn’t guarantee comfort in heavy weather, but it will buffer the ride and offer a degree of stability and security that you may feel is lacking in a light-displacement boat. If you want speed and comfort running downwind in the South Pacific, then a catamaran might be right for you. There are light-displacement catamarans and also moderately heavy displacement oceangoing catamarans about 48 to 50 feet in length that could take you just about anywhere that a shorter, stout, heavy-displacement monohull could. We choose the Tayana 37 cutter for its ruggedness in the ocean. It’s comfortable for a short-handed crew to operate, it’s economical at 37 feet and it has never let us down when in heavier ocean conditions over the past 20 years. It’s utilitarian. You might call it the Jeep of sailboats.

Phil and Lynda Christieson Kauri ketch Windora Phil and Lynda Christieson from New Zealand have owned and cruised extensively on Windora , a 43-foot Kauri ketch, for the last 26 years. They circumnavigated with their two sons in the ‘90s and are now completing a six-year cruise in the higher latitudes.

Ocean Navigator: Why did you decide to voyage in a wooden-hulled boat? Phil and Lynda Christieson: When we went looking for a cruising yacht, we were extremely lucky to find Windora , a proven offshore vessel, within our budget. Coming from New Zealand, where wooden boats are built from far superior materials, there was never any question that a wooden boat was inferior, and we learned very quickly that we had an exceptional boat. Being of wood construction, the interior is a piece of artwork, leaving you in no doubt that you are on a real boat, not a floating caravan.

ON: What are the advantages and disadvantages of this type of offshore boat? P&LC: Windora is a composite wooden boat, strip-planked with a heavy layer of epoxy glass fiber. This creates a high-strength, totally dry hull. It provides the most comfortable environment to live in, both in tropical and high-latitude climates. Repairs and maintenance can be done in the most remote places with easily available materials. There are large areas of the planet where you are treated differently because you sail a wooden boat. You are not just another white plastic boat; you stand out in the crowd. A traditionally planked wooden boat cannot be left on the hardstand for extended periods.

ON: For voyagers considering a wooden-hulled sailboat, what advice would you give? P&LC: First choice would be wood-composite construction, which lets you use two-part urethane paint systems, allows for minimum maintenance, and gives you the advantage of being able to store the boat ashore in the most extreme climates. You need to ensure the surveyor has a good understanding of wooden boats, as they are the most complex in construction of all the materials. A poorly built wooden boat can be hugely expensive to put right. Never touch any wooden vessel with iron fastenings in it.

Dave and Sherry McCampbell St. Francis 44 catamaran Soggy Paws Dave and Sherry McCampbell left Florida in May 2007 and headed west across the Pacific via the Panama Canal. They spent eight years getting across in their 1980 CSY 44 monohull. By 2015, they were ready for a faster boat and switched to a 2005 St. Francis 44 MK II catamaran. After four years exploring much of eastern Southeast Asia and a number of significant modifications, they now have the perfect cruising home.

Ocean Navigator: Why did you decide to voyage in a multihull? Dave and Sherry McCampbell: We are full-time international cruisers. There were many reasons we switched from our 1980 CSY 44 monohull to our 2005 St. Francis 44 catamaran. But the bottom line is that it was better suited to our increasing age and desire for more safety, more comfort and less maintenance. Below are the most important reasons to us that we switched. These mirror some of the most important advantages and disadvantages of a catamaran versus a monohull.

ON: What are the advantages and disadvantages of this type of offshore boat? D&SM: Here are what we see as the main advantages.

Level sailing: Cats sail relatively flat, so there is far less fatigue on a passage. Because of this, we can finally read and do computer work most of the time underway. That was rarely possible on the CSY monohull while rolling along at a 10- to 15-degree heel. This is really important for full-time cruisers and not well understood by the monohull cruising community. See the Navy study from a few years ago on page 24 of my presentation link below.

Layout: There is typically about 40 percent more room on a modern cat than on a monohull of similar length. A cat layout is much more cruising-friendly, with daily living, navigation and watch-standing areas up, and bunks, storage, heads and mechanical spaces down. The main saloon and cockpit are on the same level, so there’s no need for a ladder transit between them. It is also easier to access multiple storage lockers along the sides of two hulls instead of one, or searching for things under bunks and in the bilges.

Two engines: Modern cats generally have better speed and fuel economy while motoring. Motoring at 5 knots with one small engine properly loads up the engine and uses roughly half the diesel we used to use with the CSY. That means we can carry roughly half the fuel we used to carry for a 1,200-nm range. Two engines also means a full spare parts inventory is always on board, and there is no drama if one should develop a problem needing repair at sea.

Maintenance: The newer boat and more room mean generally easier maintenance for electrical and mechanical equipment. No teak on deck means no varnish work ever! A more modern rig makes rigging work and sail handling easier.

Unsinkability: Many modern cats won’t sink regardless of damage, due to a thick foam-cored hull, waterproof crash compartments and lack of lead keel. Our cat has a 1.25-inch foam-cored hull and deck, and is advertised as non-sinking unless really overloaded. That is a really comforting feeling while underway in deep water hundreds of miles from land. We think staying aboard is a better option than having to abandon ship into a life raft.

Stability: Cats have better stability at anchor, in a seaway or riding to a sea anchor. Little rolling means better sleep at night. It also means most things left on counters and tables will stay put underway in reasonable conditions. Availability of strong, wide bridle attachment points at the ends of the forward crossbeam reduce yawing and therefore ground tackle loads.

Speed: Most comparisons I have read indicate about a 20 percent speed increase on long passages. We rarely want to go more than about 8 knots, and we start reefing at about 7 knots. This compares to reefing at 6 knots on the CSY. We are comfortable at 7 to 8 knots on the cat. In the open sea, we consider anything more than about 9 knots uncomfortable due to increased boat motion and rig loads.

Sail handling: Wide, flat decks with little roll mean safer sail handling and reefing at sea. The jib is relatively small compared to the main, so it is easier to handle than on most monohulls. Also, no pole is required for downwind sails or a spinnaker.

Dinghy storage: Cats offer much safer and more convenient dinghy storage if lifted on high davits aft between the hulls. Typically, modern cats allow the dinghy (with motor on) to be taken out of the water easily and launched quickly. There is no need to remove the outboard and store the dinghy on the foredeck before making a passage.

Draft: The cat’s shallow draft gives many more anchoring options. This is especially important if looking for that mangrove-lined, unoccupied tropical cyclone hole. The ability to do a free haulout for repairs or a bottom paint touch-up on a beach is a huge advantage. It is easy to do on many beaches with just a few feet of tide.

Most of the monohull vs. catamaran comparisons, as well as catamaran features, are well covered in our PowerPoint presentation, “ Evaluating Modern Catamarans ,” available on our website.

ON: For voyagers considering a multihull, what advice would you give? D&SM: There is no perfect catamaran with all the features you may want, so be prepared to compromise somewhat. However, knowing what works and what does not for the cruising you plan to do is important. Be sure to research this carefully before starting to look for a cat.

With the number of catamarans being produced on the rise, there are many designs to choose from. However, not all are created equal. Although most cruisers spend 90 percent of the time in port, due consideration should also be given to features that enhance safety and comfort at sea. Most catamarans are optimized for tropics cruising and are probably not the best choices for high-latitude voyaging.

There is plenty here to consider before purchasing a cruising catamaran. Much more is on the Internet. Many modern cats are built for the lucrative charter trade and may have features that don’t work well for full-time bluewater cruising. Some of these can be corrected or improved, some cannot. Be suspicious of exaggerated dealer claims, ask for proof of anything that doesn’t seem right, and ask specific questions. Consider making a list of what to look for before going shopping.

As with almost all cat owners I’ve talked to now that we have made the switch to the “enlightened side,” we would never go back.

David Content & Roslyn Stewart Aluminum sloop Barefoot David Content and Roslyn Stewart have been sailing their boat, Barefoot , in the Pacific for eight years. Roslyn has previously sailed in Papua New Guinea and northern Europe. David has sailed extensively in the North and South Pacific.

Ocean Navigator: Why did you decide to voyage in an aluminum boat? David Content & Roslyn Stewart: My present voyaging sailboat is Barefoot , a 43-foot aluminum boat designed by Angelo Lavranos and built by Dearden Marine. I chose an aluminum boat after having already sailed more than 50,000 ocean miles in an excellent 36-foot, IOR-design fiberglass boat. Most influential in the decision was wanting a solid, strong boat that was still reasonably lightweight and would withstand the stresses and wetness experienced for weeks at a time on offshore passages.

I learned from cruisers sailing metal boats that they did not develop leaky chain plates, slack stays and shrouds, water intrusion in the rudder, loose keel bolts or squeaky interior liners at the bulkheads, even after thousands of ocean miles. For me, an aluminum boat was a better choice than steel because steel boats require a watertight paint coating on all metal surfaces. I wanted to avoid the paint maintenance, and I desired the lighter weight of an aluminum fabrication.

ON: What are the advantages and disadvantages of this type of offshore boat? DC&RS: An aluminum boat is difficult to paint and doesn’t need it above the waterline. On Barefoot , the unpainted topsides are gray and protected by a naturally developing oxide coating. Some sailors perceive this as an advantage, while others prefer to paint the topsides for cosmetic purposes.

An obvious advantage of aluminum is that the robust cleats, chocks, handrails, stanchion sockets, chain plates, anchor rollers and genoa track bases are all permanently welded directly on the deck. In addition to being extremely strong, no potentially leaky deck penetrations exist. Inside the boat, aluminum frames and stringers serve as solid attachment bases for the interior handrails, autopilot ram, steering cable sheaves, and the generator and watermaker mounts.

Non-obvious advantages of an insulated aluminum boat are numerous. One example is that the insulated hull pulls the cabin and bilge temperature toward the water temperature rather than the air temperature. This means in the tropics we’re able to stow fruit and veggies in the cool bilge, and that no deck canopy is needed to keep the cabin cool, even in the tropical sun. Conversely, when sailing at high latitudes, the water temperature is warmer than the air and that keeps the boat naturally warmer.

Two disadvantages of aluminum boats are the cost of construction and the watchfulness required to avoid corrosion problems. Well-built aluminum boats are more expensive than production fiberglass sailboats. Aluminum fabrication costs are based on the material expense of proper aluminum alloys for hull plating, frames and stringers, and on labor costs for skilled aluminum welders. The construction process is more labor intensive than fiberglass boats.

Potential corrosion sources in aluminum boats are well understood by builders these days. Following best practices in electrical wiring and equipment isolation from the hull eliminates most corrosion risks. An aluminum boat owner can prevent corrosion by learning a few unique requirements. For example, an isolation transformer must be wired in the boat if connected to shore power; a charcoal filter must be used when filling an aluminum water tank from a city chlorinated water supply; never moor the aluminum boat next to a steel boat; never use chlorine cleaners for anything (use vinegar); and always have installed and regularly check an LED light indicating a fault from a connection between the hull and the positive or negative side of the battery.

ON: What is your advice for voyagers considering an aluminum vessel? DC&RS: They should follow the same process as with the considered purchase of any boat: Talk to sailors who have a similar boat, inspect as many aluminum boats as possible, and consider having a custom boat built by selecting a good naval architect and finding a small, experienced aluminum boatyard for the build.

By Ocean Navigator

The Olson 30: Ultra Light, Ultra Fast

The complete book of sailboat buying, volume ii, june, 1987.

by Editors of the Practical Sailor

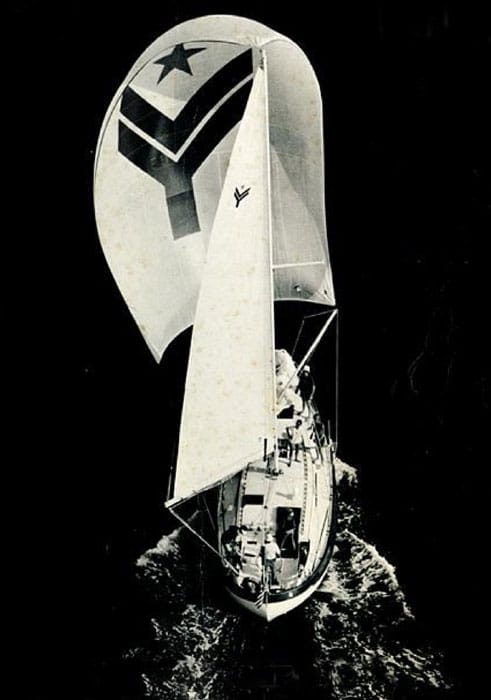

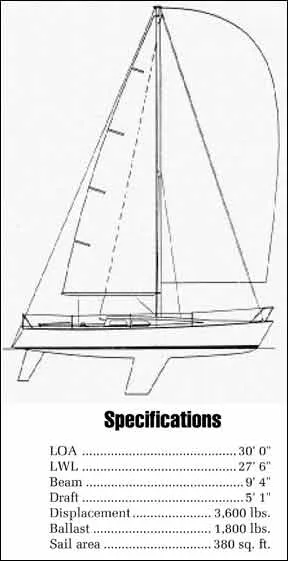

The first project for Pacific Boats was the Olson 30, which was put into production in 1978. Over 200 of these 3600-pound ULDBs were sold, and the builder claims they have gathered in sufficient numbers to support one-design racing in Seattle, the Great Lakes, Annapolis, Texas, and Long Island Sound, as well as several spots in California. Pacific Boats was a small firm that built only the Olson 30 and the Olson 40, both to quality standards.

CONSTRUCTION

Some people wonder how the ULDB can be built so light and still be seaworthy offshore. The answer lies in the fact that a light boat is subjected to much lighter loads than a heavy boat when pounding through a sea (there is tremendous saving in weight with a stripped-out interior). And perhaps more importantly, ULDB builders have construction standards that are well above average for production sailboats. The ULDB builders say that their close proximity to each other in Santa Cruz, combined with their open sharing of technology, has enabled them to achieve these high standards. The Olson 30 is no exception. The hull and deck are fiberglass, vacuumbagged over a balsa core. The process of vacuum-bagging insures maximum saturation of the laminate and core with a minimum of resin, making the hull light and stiff. The builder claims that -they have so refined the construction of the Olson 30 that each finished hull weighs within 10 pounds of the standard. The deck of the Olson does not have plywood inserts in place of the balsa where winches are mounted, instead relying on external backing plates for strength.

The hull to deck joint is an inward turned, overlapping flange, glued with a rigid compound called Reid’s adhesive, and mechanically fastened with closely spaced bolts through a slotted aluminum toerail. This provides a strong, protected joint, seaworthy-enough for sailing offshore. The aluminum toerail provides a convenient location for outboard sheet leads, but is painful for those sitting on the rail.

The Olson 30’s 1800-pound keel is deep (5′ 1″ draft) and less than five inches thick. Narrow, bolted-on keels need extra athwartship support. The Olson 30 accomplishes this with nine six-inch bolts, and one ten-inch bolt (to which the lifting eye is attached). The lead keel is faired·with polyester putty and then completely wrapped with fiberglass to seal the putty from the marine environment.

Too many builders neglect sealing autobody putty-faired keels, and too many boat owners then find the putty peeling off at a later date. The Olson’s finished keel is painted, and, on the boats we’ve seen, remarkably fair. The keel-stepped, single-spreader, tapered mast is cleanly rigged with 5/32-inch Navtec rod rigging and internal tangs. The mast section is large enough for peace of mind in heavy air. The halyards exit the mast at well-spaced intervals, to avoid creating a weak spot. The chainplates are securely attached to half-bulkheads of I-inch plywood. In addition, a tie-rod attaches the deck to the mast, tensioned by a turnbuckle. While this arrangement should provide adequate strength, we would prefer both a tie-rod and a full bulkhead that spans the width of the cabin to absorb the compressive loads that rig tension puts on the deck.

The rudder’s construction is labor-intensive but strong. Urethane foam is hand shaped to templates, then glued to a two-inch diameter solid fiberglass rudder post. The builder prefers fiberglass because it has more “memory” than aluminum or steel. Stainless steel straps are wrapped around the rudder and mechanically fastened to the post. Then the whole rudder assembly is faired, fiberglassed, and painted.

PERFORMANCE

Handling Under Sail

For those of you who agonize over whether your PHRF rating is fair, consider the ratings of ULDBs. The Santa Cruz 50 rates 0; that’s right, zero. The 67-foot Merlin has rated as low as minus 60. The Olson 30 rates anywhere from 90 to 114, depending on the local handicapper. Olson 30 owners tell us that the boat will sail to a PHRF rating of 96, but she will almost never sail to her astronomical lOR rating of 32 (the lOR heavily penalizes ULDBs). ULDBs are fast. They are apt to be on the tender side, and sail with a quick, “jerky” motion through waves. Instead of punching through waves, they ride over them. Owners tell us that they do far less cruising and far more racing than they had expected to do when they bought the boat. They say it’s more fun to race because the boat is so lively.

Like most ULDBs, the Olson 30 races best at the extremes of wind conditions-under 10 knots and over 20 knots. Although her masthead rig may appear short, it is more than powerful enough for her displacement. Owners tell us that she accelerates so quickly you can almost tack at will – a real tactical advantage in light air. In winds under 10 knots, they say she sails above her PHRF rating, both upwind and downwind. In moderate breezes it’s a different story. Once the wind gets much above 10 knots, it’s time to change down to the #2 genoa. In 15 knots, especially if the seas are choppy, it’s very difficult for the Olson 30 to save her time on boats of conventional displacement, according to three-time national champ Kevin Connally. The Olson 30 is always faster downwind, but even with a crew of 5 or 6, she just can’t hang in there upwind. In winds above 20 knots, the Olson 30 still has her problems upwind. But when she turns the weather mark the magic begins. As soon as she has enough wind to surf or plane, the Olson 30 can make up for all she looses upwind, and more. The builder claims that she has pegged speedometers at 25 knots in the big swells and strong westerlies off the coast of California. That is, of course, if the crew can keep her 1800-pound keel under her 761-square foot spinnaker. The key to competitiveness in a strong breeze is the ability of the crew. Top crews say that because she is so quick to respond, they have fewer problems handling her in heavy air. However, an inexperienced crew which cannot react quickly enough, can have big problems. “The handicappers say she can fly downwind, so they give us a low (PHRF) rating. But they don’t understand that we have sail slow, just to stay in control,” complained the crew of one new owner.

Like any higher performance class of sailboat, the Olson 30 attracts competent sailors. Hence, the boat is pushed to a higher level of overall performance, and the PHRF rating reflects this. An inexperienced sailor must realize that he may have a tougher time making her sail to this inflated rating than a boat that is less “hot.”

The two most common mistakes that new Olson 30 owners make are pinching upwind and allowing the boat to heel excessively. ULDBs cannot be sailed at the 30 degrees of heel to which many sailors of conventional boats are accustomed. To keep her flat, you must be quick to shorten sail, move the sheet leads outboard, and get more crew weight on the rail. You can’t afford to have a person sitting to leeward trimming the genoa in a 12-knot breeze. To keep her thin keel from stalling upwind, owners tell us it’s important to keep the sheets eased and the boat footing.

Being masthead-rigged, the Olson 30 needs a larger sail inventory than a fractionally rigged boat. Class rules allow one mainsail, six headsails (jibs and spinnakers) and a 75-percent storm jib. Owners who do mostly handicap racing tell us they often carry more than six headsails.

Handling Under Power

Only a few of the Olson 30s sold were equipped with inboard power. This is because the extra weight of the inboard and the drag of the propeller, strut and shaft are a real disadvantage when racing against the majority of Olson 30s, which are equipped with outboard motors. The Olson 30 is just barely light enough to be pushed by a four to five horsepower outboard. It takes a 7.5 horse outboard to push the Olson 30 at 6.5 knots in a flat calm. The Olson’s raked transom requires an extra long outboard bracket, which puts the engine throttle and shift out of reach for anyone much less than 6 feet tall: “A real pain,” said one owner. Storage is a problem, too. Even if you could get the outboard through the stern lazarette’s small hatch, you wouldn’t want to race with the extra weight so far aft. As a result, most owners end up storing the outboard on the cabin sole. The inboard was an optional, 154-pound, 7-horsepower, BMW diesel. Unlike most boats, the Olson 30 will probably never return the investment in an inboard when the boat is sold. It detracts from the boat’s primary purpose-racing.

Without an inboard, owners have a problem charging the battery. Owners who race with extensive electronics have to take the battery ashore after every race for recharging. If the Olson 30 weren’t such a joy to sail in light air, and so maneuverable in tight places, the lack of inboard power would be a serious enough drawback to turn away more sailors than it does.

Deck Layout

In most respects, the Olson 30 is a good sea boat. Although the cockpit is 6-1/2 feet long, the wide seats and narrow floor result in a relatively small cockpit volume, so little sea water can collect in the cockpit if the boat is pooped or knocked down. However, foot room is restricted, while the width of the seats makes it awkward to brace your legs on the leeward seat. The seats themselves

There are gutters to drain water off the leeward seat. The long mainsheet traveler is mounted across the cockpit. The Olson 30’s single companionway dropboard is latchable from inside the cabin, a real necessity in a storm offshore. A man-overboard pole tube in the stern is standard equipment. Teak toerails on the cockpit combing and on the forward part of the cabin house provide good footing, and there are handholds on the after part of the cabin house. The tapered aluminum stanchions are set into sockets molded into the deck and glassed to the inside of the hull, a strong, clean, leak-proof system. However, the stanchions are not glued or mechanically fastened into the sockets. If pulled upwards with great force they can be pulled out. We feel this is a safety hazard. Tight lifelines would help prevent this from happening, but most racing crews tend to leave them slightly loose so they can lean further outboard when hanging over the rail upwind. If the stanchions were fastened into the sockets with bolts or screws they would undoubtedly leak. A leakproof solution to this problem should be devised and made available to Olson 30 owners. The cockpit has two drains of adequate diameter. The bilge pump, a Guzzler 500, is mounted in the cockpit. As is common on most boats, the stern lazarette is not sealed off from the rest of the interior. If the boat were pooped or knocked down with the lazarette open, water could rush below through the lazarette relatively unrestricted. As the Olson 30 has a shallow sump, there is little place for water to go except above the cabin sole. A “paint-roller” type non-skid is molded into the Olson 30’s deck It provides excellent traction, but it is more difficult to keep clean than conventional patterned non-skid.

The Olson 30 is well laid out with hardware of reasonable, but not exceptional, quality. All halyards and pole controls lead to the cockpit through Easylock 1 clutch stoppers. The Easylocks are barely big enough to hold the halyards; they slip an inch under heavy loads. Older Olsons were equipped with Howard Rope Clutches. The Howards had’ a history of breaking (although the manufacturer has now corrected the problem). The primary winches, Barient 22s, are also barely adequate. Some owners we talked to had replaced them with more powerful models. Schaefer headsail track cars are standard equipment. One owner complained that he had to replace them with Merrimans because the Schaefers kept slipping.

Leading the vang to either rail and leading the reefing lines aft is also recommended. The mast partner is snug, leaving no space for mast blocks. The mast step is movable to adjust the prebend of the spar. The partner has a lip, over which a neoprene collar fits. The collar is hose-clamped to the mast. This should make a watertight mast boot. However, on the boat we sailed, the bail to which the boom vang attached obstructed the collar, causing water to collect and drain into the cabin.

The yolked backstay is adjustable from either quarter of the stem, one side being a 2:1 gross adjustment and the other side being an 8:1 fine tune. A Headfoil II is standard equipment. There is a babystay led to a track with a 6:1purchase for easy adjustment. The track is tied to the thin plywood of the forward V -berth with a wire and a turnbuckle. On the boat we sailed, the padeye to which the babystay tie rod is attached was seen to be tearing out from the V-berth.

There is a port in the deck directly over the lifting eye in the bilge. This makes for quick and easy drysailing. The Olson 30, however, is not easily trailered; her 3600 pounds is too much for all but the largest cars, and her 9.3-foot beam requires a special trailering permit.

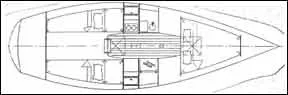

The Olson 30 is cramped belowdecks. Her low deckhouse and substantial sheer may make her one of the sexiest-looking production boats on the water, but the price is headroom of only four feet, five inches. There is not even enough headroom for comfortable stooping. Moving about below is a real grind for an average-sized person. To offset the confinement of the interior, the builder has done everything possible to make it light and airy. In addition to the Lexan forward hatch and cabin house windows, the companionway hatch also has a Lexan insert. The inside of the hull is smooth sanded and finished with white gelcoat. There are no full-height bulkheads dividing the cabin. All the furniture is built of lightweight, light-colored, 3/8″ Scandanavian, seven-ply plywood.

The joinerwork is above average and all of the bulkhead and furniture tabbing is extremely neat. There isn’t much to the Olson 30’s interior, but what there is has been done with commendable craftmanship. The cabin sole is narrow, and with the lack of headroom, the woodwork is susceptible to being dinged and scratched from equipment like outboard motors. Once the finish on the wood is broken, it quickly absorbs water, which collects in the shallow bilge. ‘

The Olson 30 is not a comfortable cruiser. Even after you’ve taken all the racing sails ashore, the belowdecks is barely habitable. To save weight the quarterberths are made of thin cushions sewn to vinyl and hung from pipes.These pipe berths are comfortable, but the cushions are not easily removed. Should they get wet it’s likely they would stay wet for some time. Two seabags are hung on sail tracks above the quarter berths, which should help to insure that some clothes stay dry.

Just forward of each quarterberth is a small uncushioned seat locker. Behind each seat is a small portable ice cooler. In one seat locker is the stove, an Origo 3000, which slides up and out of the locker on tracks. The Ongo is a top-of-theline unpressurized alcohol stove, but to operate it the cook must kneel on the cabin sole. To work at the navigation station, which is in front of the starboard seat, you must sit sideways. In front of the port seat is the lavette, with a hand water pump and a removable, shallow, drainless sink. Drainless sinks eliminate the need for a through-hull fitting-a good idea-but they should be deep, not shallow.

Although there are curtains which can be drawn across the V-berth, we think human dignity deserves an enclosed head, especially on a 30’ boat. The V-berth is large and easy to climb into, but there are no shelves above it or a storage locker in the empty bow. In short, if you plan to cruise for more than a weekend, you’d better like roughing it.

CONCLUSIONS

A completely equipped Olson 30 ran about $35,000. Today, a used one will cost from $24,000 to $28,000 ( note – this was written in 1987, prices are lower in 2015 ). What do you get for this? You get a boat that’s well built, seaworthy, and reasonably well laid out. You get a boat that, in light air, will sail as fast as boats costing nearly twice as much. Downwind in heavy air, you have a creature that will blow your mind and leave everything (except a bigger ULDB) in your wake. If you spend all of your sailing time racing in a PHRF fleet in an area where light or heavy air dominates, the Olson 30 will probably give you more pleasure for your dollar than almost anything afloat.

However, if you race in moderate air or enjoy more than an occasional short cruise, you are likely to be very disappointed. Before you consider the Olson 30, you must realistically evaluate your abilities as a sailor. There’s nothing worse, after finding out that you can’t race a boat to her potential, than realizing that she is of little use for any other aspect of our sport.

The Complete Book of Sailboat Buying, Volume II

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

- Boat Displacement

Boat Displacement/Length Ratio & Other Key Performance Indicators

A boat's displacement is defined as the weight of the volume of water displaced by it when afloat. It's normally described in long tons (1 ton = 2,240 lbs) but it can also be stated in cubic feet, with 1 ft 3 = 64lb.

Like hullspeed, displacement doesn't mean much unless compared to waterline length,so you need to take a look at the Displacement/Length Ratio to compare the relative heaviness of boats no matter what their size.

Similarly, sail area doesn't tell you much about a boat's likely performance unless compared to its displacement, which is why we have the Sail Area/Displacement Ratio.

Let's take a look at both of these displacement related ratios in turn...

The Displacement/Length Ratio

Displacement/length categories:.

Under 90 - Ultralight;

90 to 180 - Light;

180 to 270 - Moderate;

270 to 360 - Heavy;

360 and over - Ultraheavy;

The formula for calculating the Displacement/Length Ratio is:

D/(0.01L) 3 , where...

- D is the boat displacement in tons (1 ton = 2,240lb), and

- L is the waterline length in feet.

An ultra-light racing yacht may have a D/L Ratio of 80 or so, a light cruiser/racer would be around 140, a moderate displacement cruiser be around 230, a heavy displacement boat will be around 320 while a Colin Archer type super- heavy displacement cruiser may boast a D/L ratio of 400+.

As immersed volume and displacement are proportional, a heavy displacement yacht will have to heave aside a greater mass of water than its light displacement cousin.

Or put another way, the lower D/L Ratio vessel will have a lower resistance to forward motion than the higher D/L ratio vessel, and will be quicker as a result.

That's a longwinded way of saying that the greater the mass, the greater the power required to shift it.

That power is of course derived from the force of the wind acting upon the sails, and the greater the sail area the greater the power produced for a given wind strength.

A Few Examples...

The Sail Area/Displacement Ratio

The formula for calculating the Sail Area/Displacement Ratio is:

SA/(DISPL) 0.67 , where...

- SA is sail area in square feet, and

- DISPL is boat displacement in cubic feet

Clearly then, performance is a function of both power and weight, or sail area and displacement.

Sail Area/Displacement ratios range from around 14 for a lightly canvassed motor-sailor to 20 or so for an ocean racer.

Calculating Sail Area

Mainsail Area

Calculating the area of the mainsail is simple. After all, it's just a right-angled triangle so:

Area = (Base x Height)/2 = (Foot x Luff)/2

OK, it won't be spot on if the sail has some roach, but it'll be near enough. Having said that, for a fully-battened, heavily roached sail you could add 10 to 15% to be more accurate.

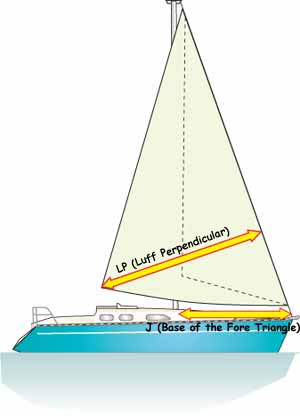

Foresail Area

The foresail would be just as easy if it exactly fitted the fore-triangle but usually the sail will be high-cut or will overlap the mast - or both.

So the calculation becomes:

Sail Area = (luff perpendicular x luff)/2

For more on this subject, take a look at Understanding Sail Dimensions...

A Final Word on Boat Displacement etc...

So to summarize, the criteria associated with good performance under sail are:

- Boat Displacement: the lower the better, as the power requirement is directly proportional to displacement. Provided, of course, that light displacement doesn't come at the cost of structural integrity;

- Waterline length: the longer the better, as wave-making resistance is inversely proportional to waterline length;

- Wetted area: the less the better, particularly in areas where light airs prevail, as hull drag is directly proportional to wetted area;

- Sail area: the more the better, within reason, as power production is directly proportional to sail area. Having to reef early is much less frustrating than wishing you had an extra metre or so on the mast when the wind falls away.

- For real 'Get Up and Go' a sailboat will have a low Displacement/Length ratio and a high Sail Area/Displacement Ratio .

But performance in an offshore cruising sailboat isn't just about speed. Whilst, as part of the deal for getting their hands on the silverware, a racing crew will cheerfully accept the high degree of attentiveness needed to keep a twitchy racing machine on her feet, a cruising sailor most definitely won't.

For us, a degree of speed will be readily sacrificed for a boat that's easy on the helm, and which rewards its crew with a gentler motion and more comfortable ride.

And whilst talking of comfort, Ted Brewer's 'Comfort Ratio' has much to do with Boat Displacement.

You might like to take a look at these...

The Righting Moment Is a Key Factor to a Sailboat's Stability

Whilst it's the righting moment that influences a sailboat's static stability, it's the dynamic stability that has the larger affect on seaworthiness. And here's what it means to us

Importance of the Prismatic Coefficient in Sailboat Hull Design

The prismatic coefficient is associated with the fullness of fineness of the ends of a boat's hull, but why is this important and how does it affect performance?

Understanding Sailboat Design Ratios

The formulae for sailboat design ratios are quite complex, but with this tool the calculations are done for you in an instant!

How Gz Curves Reveal the Truth about A Sailboat's Stability

Gz curves are a graphic representation as to how a sailboat's righting moment changes with heel angle, identifying the heel angle at which the boat will capsize rather than come back upright

Some Sailboat Interiors are Not Suitable for Offshore Sailing

Examples of practical sailboat interiors that work for serious offshore sailing, compared with those that are more suited for coastal sailing and marina hopping

Recent Articles

'Natalya', a Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 54DS for Sale

Mar 17, 24 04:07 PM

'Wahoo', a Hunter Passage 42 for Sale

Mar 17, 24 08:13 AM

Used Sailing Equipment For Sale

Feb 28, 24 05:58 AM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

Displacement

There are three main types of displacement. Which one is used in stating specifications is frequently a mystery, since designers and/ or builders and marketers seldom identify which type they are reporting. Hence, unfortunately, the type of displacement quoted in sales brochures and boat magazines varies, and this can cause confusion and hinder calculation of some performance parameters such as the D/L ratio (see next page).

Dry displacement, sometimes called light displacement, is the hull and rig weight excluding weight of crew, equipment, fuel and water, stores, outboard engine if any, and so on. This number is helpful in determining trailer-towing weight. However, "dry" displacement, if shown in brochures, may or may not include water ballast on boats that use that type of ballast.

Loaded or sailing displacement is the weight as equipped for sailing, including crew, equipment, fuel and water, stores, outboard engine if any, and so on.

Half-load displacement is a variation on loaded displacement, being the weight with normal crew and equipment, but with half-filled fuel and water tanks. In theory, either loaded or half-load displacement should be used for calculating various performance ratios such as B/D, SA/D, and D/L (see pages 9, 12, and 13).

Differences between displacement types can be substantial, particularly in small cruisers. For example, designer Charlie Wittholz specifies that the loaded displacement of the Cape Cod Cat 17 is 2,800 lbs. However, he suggests taking off two or three people and their gear, weighing approximately 600 lbs. in total, to obtain the boat's trailering, or dry displacement. Thus he estimates dry displacement at around 2,200 lbs.

But in reality, we believe most sales brochures use dry displacement as the measure of displacement for all purposes—and for lack of a better method of determining half-load or full displacement using our vast collection of sales brochures, we are stuck with using whatever displacement the sales brochures declare. Consequently, in this guide, the number reported is usually dry displacement. Typically, sailing magazines and books also use this same dry displacement to calculate SA/D and D/L ratios. Technically, this is incorrect, but for comparing one boat to another, if done consistently, no great injustice is done.

Even if displacement reported in sales brochures uses the correct definitions, the number can still be grossly in error. For example, in the original C&C Bluejacket 23 sales brochure, the displacement was erroneously listed as 6,000 pounds—much too high for a sleek racer-cruiser of that size. Later the number was amended, without explanation, to 4,000 pounds.

Continue reading here: Sail Area Displacement Ratio SAD

Was this article helpful?

Related Posts

- Ballast Displacement BD Ratio

- Catamaran Design Guide - Catamarans Guide

- Displacement Length Ratio DL

- LOD and LOA - Cruising Sailboats Reference

Readers' Questions

What boat builders use half load displacement?

Most boat builders use half-load displacement when calculating the displacement of a boat. This calculation is typically used to determine the weight of a boat's hull and the amount of ballast needed for a vessel to remain stable in the water. The displacement includes the weight of the boat transom and hull, plus the weight of the fuel, water, and occupants.

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

40 Best Sailboats

- By Cruising World Editors

- Updated: April 18, 2019

Sailors are certainly passionate about their boats, and if you doubt that bold statement, try posting an article dubbed “ 40 Best Sailboats ” and see what happens.

Barely had the list gone live, when one reader responded, “Where do I begin? So many glaring omissions!” Like scores of others, he listed a number of sailboats and brands that we were too stupid to think of, but unlike some, he did sign off on a somewhat upbeat note: “If it weren’t for the presence of the Bermuda 40 in Cruising World’s list, I wouldn’t even have bothered to vote.”

By vote, he means that he, like hundreds of other readers, took the time to click through to an accompanying page where we asked you to help us reshuffle our alphabetical listing of noteworthy production sailboats so that we could rank them instead by popularity. So we ask you to keep in mind that this list of the best sailboats was created by our readers.

The quest to building this list all began with such a simple question, one that’s probably been posed at one time or another in any bar where sailors meet to raise a glass or two: If you had to pick, what’re the best sailboats ever built?

In no time, a dozen or more from a variety of sailboat manufacturers were on the table and the debate was on. And so, having fun with it, we decided to put the same question to a handful of CW ‘s friends: writers and sailors and designers and builders whose opinions we value. Their favorites poured in and soon an inkling of a list began to take shape. To corral things a bit and avoid going all the way back to Joshua Slocum and his venerable Spray —Hell, to Noah and his infamous Ark —we decided to focus our concentration on production monohull sailboats, which literally opened up the sport to anyone who wanted to get out on the water. And since CW is on the verge or turning 40, we decided that would be a nice round number at which to draw the line and usher in our coming ruby anniversary.

If you enjoy scrolling through this list, which includes all types of sailboats, then perhaps you would also be interested in browsing our list of the Best Cruising Sailboats . Check it out and, of course, feel free to add your favorite boat, too. Here at Cruising World , we like nothing better than talking about boats, and it turns out, so do you.

40. Moore 24

39. Pearson Vanguard

38. Dufour Arpege 30

37. Alerion Express 28

36. Mason 43/44

35. Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 43DS

34. Nor’Sea 27

33. Freedom 40

32. Beneteau Sense 50

31. Nonsuch 30

30. Swan 44

29. C&C Landfall 38

28. Gulfstar 50

27. Sabre 36

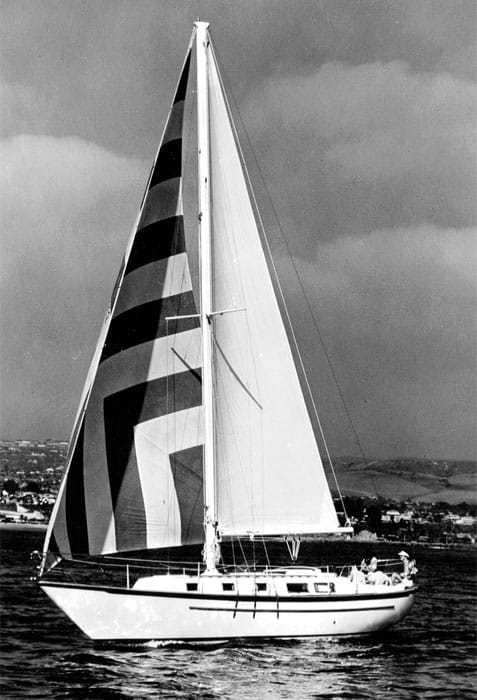

26. Pearson Triton

25. Islander 36

24. Gozzard 36

23. Bristol 40

22. Tartan 34

21. Morgan Out Island 41

20. Hylas 49

19. Contessa 26

18. Whitby 42

17. Columbia 50

16. Morris 36

15. Hunter 356

13. Beneteau 423

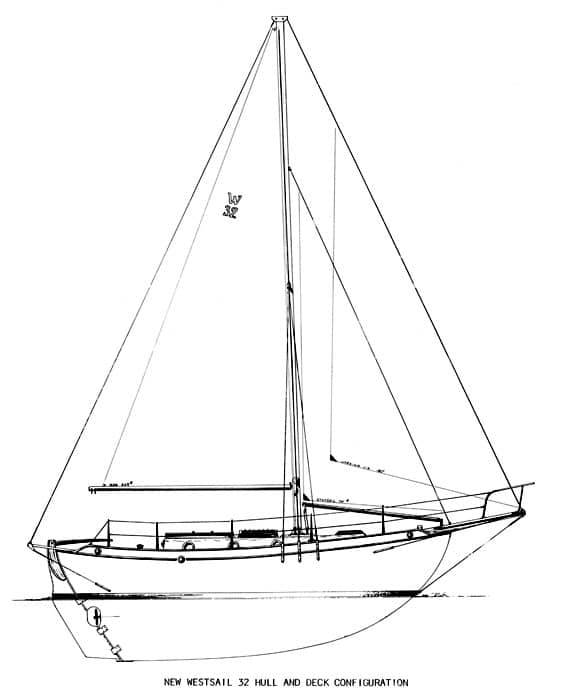

12. Westsail 32

10. Alberg 30

9. Island Packet 38

8. Passport 40

7. Tayana 37

6. Peterson 44

5. Pacific Seacraft 37

4. Hallberg-Rassy 42

3. Catalina 30

2. Hinckley Bermuda 40

1. Valiant 40

- More: monohull , Sailboats

- More Sailboats

New to the Fleet: Pegasus Yachts 50

Balance 442 “Lasai” Set to Debut

Sailboat Review: Tartan 455

Meet the Bali 5.8

Cruising the Northwest Passage

A Legendary Sail

10 Best Sailing Movies of All Time

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

How to Sell Your Boat

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Open Transom Pros and Cons

Leaping Into Lithium

The Importance of Sea State in Weather Planning

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

When Should We Retire Dyneema Stays and Running Rigging?

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

How Dangerous is Your Shore Power?

DIY survey of boat solar and wind turbine systems

What’s Involved in Setting Up a Lithium Battery System?

The Scraper-only Approach to Bottom Paint Removal

Can You Recoat Dyneema?

Gonytia Hot Knife Proves its Mettle

Where Winches Dare to Go

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Rhumb Lines: Livin’ the Wharf Rat Life

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Safer Sailing: Add Leg Loops to Your Harness

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Sailboat Reviews

This speedster is as specialized as it gets; mind-blowing performance, but almost no living space.

The Olson 30 is of a breed of sailboats born in Santa Cruz, California called the ULDB , an acronym for ultra light displacement boat. ULDBs are big dinghies—long on the waterline, short on the interior, narrow on the beam, and very light on both the displacement and the price tag. ULDBs attract a different kind of sailor—the type for whom performance means everything.

For some yachting traditionalists, the arrival of ULDB has been a hard pill to swallow. Part of this is simple resentment of a ULDB’s ability to sail boat for-boat with a racer-cruiser up to 15′ longer (and a whole lot more expensive). Part of it is the realization that, to sail a ULDB might mean having to learn a whole new set of sailing skills. Part of it is a reaction to the near-manic enthusiasts of Santa Cruz, where nearly 100 ULDBs race for pure fun—without the help of race committees, protest committees, or handicaps (in Santa Cruz, IOR is a dirty word). And part of the traditionalists’ resentment is their gut feeling that ULDBs aren’t real yachts.

In 1970, Californian George Olson tried an experiment and created the first ULDB. He thought if he took a boat with the same displacement and sail area as a Cal 20, but made it longer and narrower, it might go faster. The boat he built was called Grendel and it did go faster than a Cal 20, much faster than anyone had expected. The plug for Grendel was later widened by Santa Cruz boatbuilder Ran Moors, and used to make the mold for the Moore 24, a now-popular ULDB one-design.

In the meantime, George Olson had joined up with another Santa Cruz builder by the name of Bill Lee, and together they designed and built the Santa Cruz 27. Olson also helped Lee build his 1977 Transpac winner Merlin, a 67′, 20,000 pound monster of a ULDB (she was subsequently legislated out of theTranspac race). Then Olson and several other of Lee’s employees started their own boatbuilding firm (in Santa Cruz, of course) called Pacific Boats. The first project for Pacific Boats was the Olson 30, which was put into production in 1978. Pacific Boats later became Olson/Ericson, and produced a 25 and a 40. The latest incarnation of the 30 is called the 911.

Construction

Some people wonder how ULDBs can be built so light, yet still be seaworthy offshore. The answer is three-fold: first, a light boat is subjected to lighter loads, when pounding through a heavy sea, than a boat of greater displacement. Second, there is a tremendous saving in weight with a stripped-out interior. Third, as a whole, ULDB builders have construction standards that are well above average for production sailboats. The ULDB builders say that their close proximity to each other in Santa Cruz combined with an open sharing of technology has enabled them to achieve these standards.

The Olson 30 is no exception. The hull and deck are fiberglass vacuum-bagged over a balsa core. The process of vacuum-bagging insures maximum saturation of the laminate and core with a minimum of resin, making the hull light and stiff. The builder claims that they have so refined the construction of the Olson 30 that each finished hull weighs within 10 pounds of the standard. The deck of the Olson does not have plywood inserts in place of the balsa where winches are mounted, instead relying on external backing plates for strength.

The hull-to-deck joint is an inward turned overlapping flange, glued with a rigid compound called Reid’s adhesive, and mechanically fastened with closely spaced bolts through a slotted aluminum toerail. This provides a strong, protected joint, seaworthy enough for sailing offshore. We would prefer a semi-rigid adhesive, however, because it is less likely to fracture and cause a leak in the event of a hard collision. The aluminum toerail provides a convenient location for outboard sheet leads, but is painful to those sitting on the rail.

The Olson 30’s 1,800 pound keel is deep (5.1′ draft) and less than 5″ thick. Narrow, bolted-on keels need extra athwartships support. The Olson 30 accomplishes this with nine 5/8″ bolts and one 1″ bolt (to which the lifting eye is attached). The lead keel is faired with auto body putty and then completely wrapped with fiberglass to seal the putty from the marine environment. Too many builders neglect sealing auto body putty-faired keels, and too many boat owners then find the putty peeling off at a later date. The Olson’s finished keel is painted, and, on the boats we have seen, remarkably fair.

The keel-stepped, single-spreader, tapered mast is cleanly rigged with 5/32″ Navtec rod rigging and internal tangs. The mast section is big enough for peace of mind in heavy air. The halyards exit the mast at well-spaced intervals, so as not to create a weak spot.The shroud chainplates are securely attached to half-bulkheads of 1″ plywood. In addition, a tie rod attaches the deck to the mast, tensioned by a turnbuckle. While this arrangement should provide adequate strength, we would prefer both a tie rod and a full bulkhead that spans the width of the cabin so as to absorb the compressive loads that the tension of the rig puts on the deck.

The rudder’s construction is labor intensive, but strong. Urethane foam is hand shaped to templates, then glued to a 4″ thick solid fiberglass rudder post. The builder prefers fiberglass because it has more “memory” than aluminum or steel. Stainless steel straps are wrapped around the rudder and mechanically fastened to the post. Then the whole assembly is faired, fiberglassed, and painted.

Handling Under Sail

For those of you who agonize over whether your PHRF rating is fair, consider the ratings of ULDBs. The Santa Cruz 50 rates 0; that’s right— zero . The 67′ Merlin has rated as low as minus 60. The Olson 30 rates anywhere from 90 to 114, depending on the local handicapper. Olson 30 owners tell us that the boat will sail to a PHRF rating of 96, but she will almost never sail to her astronomical IOR rating of 32′ (the IOR heavily penalizes ULDBs).