An epic travelogue, brimming with the excitement of discovery. With characteristic panache, Venter unveils the teeming array of bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotes that crowd our planet’s oceans. His research will undoubtedly shape our understanding of the global ecosystem for decades to come.

An exhilarating account of how creative science is accomplished. Few would guess just how many microbes live with us and how much they contribute to human health, both directly in our bodies and by making sure the air we breathe supports life. I have always loved bacteria, but after reading this I have an enhanced appreciation of their value to life on this planet. I highly recommend it.

The Voyage of Sorcerer II combines panoramic linguistic imagery with trenchant scientific insights to provide the reader a virtual seat aboard the most important ship of discovery since Darwin’s Beagle. Venter reveals to us why Earth should be called ‘Water’ and why the ocean’s microscopic life is our deepest and most magical reservoir of genetic diversity. This page-turner gives each of us the thrill of seeing our planet’s largest universe through the brilliant, intrepid eyes of the scientist who has done more than anyone to unlock the secrets of life.

A tour de force. Following in the paths of the Beagle and the Challenger, Venter has expanded biology’s horizons. This book explores microbial life on a global scale, providing cutting-edge solutions to problems of environmental change.

A fascinating inside look at Venter’s historic expeditions that makes the experiences, the analysis, and the transformative discoveries come alive.

We humans may think we are the most important species on Earth, but we’re actually just bit players in a far broader and more complex microbial world. In this exciting journey into that deeper world, Venter and Duncan expand our scope of what it means to be alive.

A ripping tale of how a sailing adventure and science can be combined to revolutionize our understanding of our bodies, the oceans, and the planet.

Microlands combines panoramic linguistic imagery with trenchant scientific insights to provide the reader a virtual seat aboard the most important ship of discovery since Darwin’s Beagle. Venter reveals to us why Earth should be called ‘Water’ and why the ocean’s microscopic life is our deepest and most magical reservoir of genetic diversity. This page-turner gives each of us the thrill of seeing our planet’s largest universe through the brilliant, intrepid eyes of the scientist who has done more than anyone to unlock the secrets of life.

After sequencing the human genome and embarking on a reimagining of his Institute and future research, J. Craig Venter, Ph.D. set upon a project combining his two loves: sailing and science. In 2004, after a successful pilot project where the DNA was collected and sequenced at the Bermuda Atlantic Time Series site, Dr. Venter and a team from his Institute launched the Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling (GOS) Expedition.

Inspired by 19th century sea voyages like Charles Darwin’s on the H.M.S. Beagle and Captain George Nares on the H.M.S. Challenger, the Sorcerer II circumnavigated the globe for more than two years, covering a staggering 32,000 nautical miles, visiting 23 different countries and island groups on four continents. The expedition continued for fifteen years, collecting tens of millions of marine microbes found in the global oceans and in the process has changed our understanding of this critical resource that sustains us.

In “The Voyage of Sorcerer II,” Dr. Venter and science writer David Ewing Duncan tell the remarkable story of these expeditions and of the momentous discoveries that ensued: of plant-like bacteria that get their energy from the sun, proteins that metabolize vast amounts of hydrogen, and microbes whose genes shield them from ultraviolet light. The result was a massive library of millions of unknown genes, thousands of unseen protein families, and new lineages of bacteria that revealed the unimaginable complexity of life on earth. Yet despite this exquisite diversity, Venter encountered sobering reminders of how human activity is disturbing the delicate microbial ecosystem that nurtures life on earth. In the face of unprecedented climate change, Venter and Duncan show how we can harness microbial genomes to develop alternative sources of energy, food, and medicine that might ultimately avert our destruction.

A captivating story of exploration and discovery, “The Voyage of Sorcerer II” restores microbes to their rightful place as crucial partners in our evolutionary past and guides to our future.

In “Microlands,” Dr. Venter and science writer David Ewing Duncan tell the remarkable story of these expeditions and of the momentous discoveries that ensued: of plant-like bacteria that get their energy from the sun, proteins that metabolize vast amounts of hydrogen, and microbes whose genes shield them from ultraviolet light. The result was a massive library of millions of unknown genes, thousands of unseen protein families, and new lineages of bacteria that revealed the unimaginable complexity of life on earth. Yet despite this exquisite diversity, Venter encountered sobering reminders of how human activity is disturbing the delicate microbial ecosystem that nurtures life on earth. In the face of unprecedented climate change, Venter and Duncan show how we can harness microbial genomes to develop alternative sources of energy, food, and medicine that might ultimately avert our destruction.

A captivating story of exploration and discovery, “Microlands” restores microbes to their rightful place as crucial partners in our evolutionary past and guides to our future.

- MarketPlace

- Digital Archives

- Order A Copy

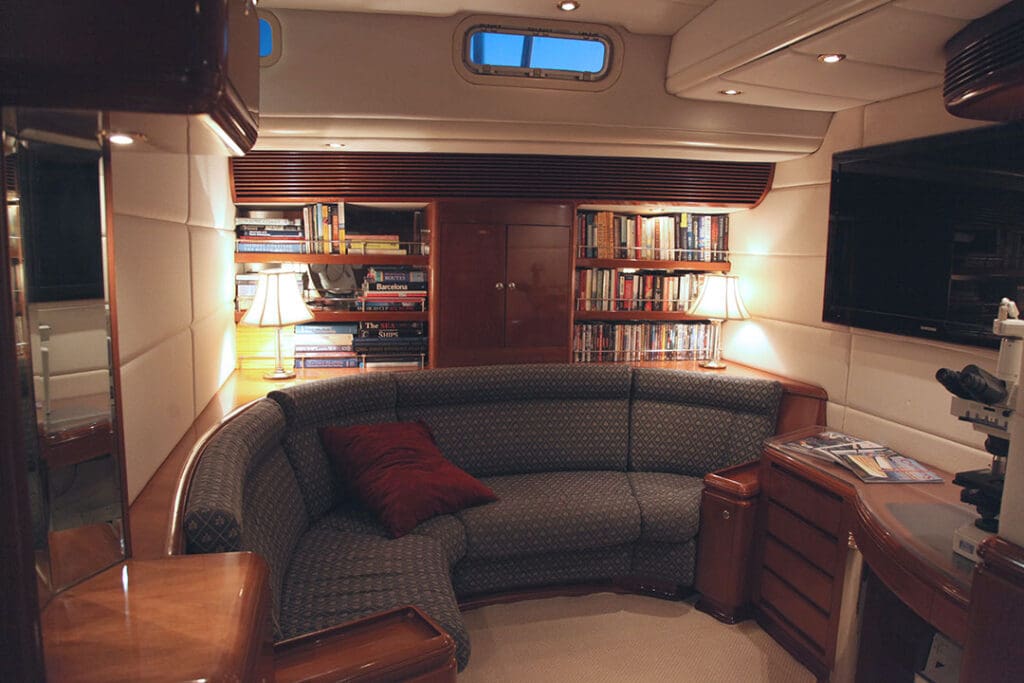

Boat Focus: Sorcerer II

E xplorations of the globe under sail, like Darwin’s voyage aboard the ship Beagle and the voyage of the Royal Navy ship Challenger in the 1870s, were scientific milestones that greatly increased our knowledge of the planet. For biological scientist and lifelong sailor Dr. J. Craig Venter those passages provided a major inspiration for his extensive voyaging aboard his 95-foot sloop Sorcerer II . On two separate expeditions Venter, along with a group of fellow scientists and Sorcerer II ’s crew, gathered biological samples from the world’s oceans. Sorcerer II sailed more than 65,000 miles and harvested a vast biological trove that is being used to expand knowledge of the world’s biological organisms.

In the 1990s, Venter and his team successfully sequenced the human genome in parallel with a government-funded effort. Venter also founded the biotech firms Celera Genomics, the Institute for Genomic Research and the J. Craig Venter Institute.

During a recent phone call Venter said that when he was serving in the Navy during the Vietnam War and stationed at a Navy facility in Da Nang, he often thought about sailing. “The idea of the sailing around the world helped keep me sane,” Venter said. When deciding to launch his first worldwide sampling expedition he realized he could combine his desire to do a circumnavigation with science. “A chance to do that and do my research at the same time was a phenomenal opportunity.” Venter and David Ewing Duncan have written a new book about the sampling expeditions called The Voyage of Sorcerer II published in September by Harvard University Press.

Venter and crew collected samples every 200 miles by pumping 200 to 400 liters of seawater aboard and running it through a series of increasingly smaller filters designed to capture ever smaller denizens of the aquatic world. The filters with their specimens were then frozen on board and when Sorcerer II arrived at a port that had air freight service the frozen filters were airlifted back to Venter’s lab for analysis. The amount of data acquired was staggering. “We discovered more species on these voyages,” Venter said, “than the entire history of scientific discovery put together.”

During Venter’s research voyages, the boat — currently under different ownership, Venter sold it in 2019 — was equipped with a 300 horsepower 6CTA8 3M Cummins diesel with an adjustable pitch Max Prop propeller and fuel tankage of 2,324 gallons and water tankage of 634 gallons. Its fin keel has a draft of 10.2 feet. Even though a large boat Sorcerer II has manual cable steering. It was also equipped with bow and stern thrusters, water maker, two gensets and a host of other gear for crew comfort while conducting its research worldwide.

The tough hull of e-glass and Kevlar was well suited to the demands of many ocean miles. An excerpt from the Venter and Duncan’s book provides a glimpse of how Sorcerer II ’s captain viewed the vessel. “Sorcerer is not too big and not too small,” said Captain Charlie Howard, describing his vessel…. “She is smart and well put together with the best components and a lot of thought and engineering. She has long legs and once took us almost six thousand miles on one load of fuel from Cape Town to Antigua. She thrives on lots of attention and when you don’t give her the attention, she gives you surprises. She is a good friend when the going is rough, and she has never let me down.” n

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

James Shreeve

Craig Venter's Epic Voyage to Redefine the Origin of the Species

Picture this: You are standing at the edge of a lagoon on a South Pacific island. The nearest village is 20 miles away, reachable only by boat. The water is as clear as air. Overhead, white fairy terns hover and peep among the coconut trees. Perhaps 100 yards away, you see a man strolling in the shallows. He is bald, bearded, and buck naked. He stoops every once in a while to pick up a shell or examine something in the sand.

A lot of people wonder what happened to J. Craig Venter, the maverick biologist who a few years ago raced the US government to sequence the human genetic code. Well, you’ve found him. His pate is sunburned, and the beard is new since he graced the covers of Time and BusinessWeek . It makes him look younger and more relaxed - not that I ever saw him looking very tense, even when the genome race got ugly and his enemies were closing in. This afternoon, the only adversary he has to contend with is the occasional no-see-um nipping at some tender body part. "Nobody out here has ever heard of the human genome," he told me a week ago, when I first joined him in French Polynesia. "It’s great."

Venter is here not just to enjoy himself, though he has been doing plenty of that. What separates him from your average 58-year-old nude beachcomber is that he’s in the midst of a scientific enterprise as ambitious as anything he’s ever done. Leaving colleagues and rivals to comb through the finished human code in search of individual genes, he has decided to sequence the genome of Mother Earth.

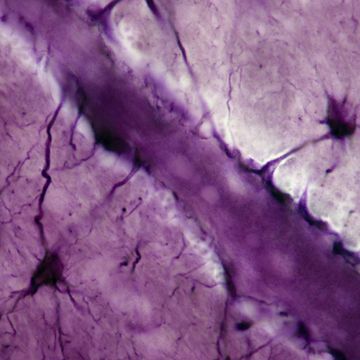

What we think of as life on this planet is only the surface layer of a vast undiscovered world. The great majority of Earth’s species are bacteria and other microorganisms. They form the bottom of the food chain and orchestrate the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrients through the ecosystem. They are the dark matter of life. They may also hold the key to generating a near-infinite amount of energy, developing powerful pharmaceuticals, and cleaning up the ecological messes our species has made. But we don’t really know what they can do, because we don’t even know what they are.

Venter wants to change that. He’s circling the globe in his luxury yacht the Sorcerer II on an expedition that updates the great scientific voyages of the 18th and 19th centuries, notably Charles Darwin’s journey aboard HMS Beagle . But instead of bagging his finds in bottles and gunnysacks, Venter is capturing their DNA on filter paper and shipping it to be sequenced and analyzed at his headquarters in Rockville, Maryland. The hope is to uncover tens or even hundreds of millions of new genes, an immense bolus of information on Earth’s biodiversity. In the process, he’s having a hell of a good time and getting a very good tan. "We’re talking about an unknown world of enormous importance," says Harvard biologist and writer E. O. Wilson, who serves on the scientific advisory board of the Sorcerer II expedition. "Venter is one of the first to get serious about exploring that world in its totality. This is a guy who thinks big and acts accordingly."

He certainly talks big. "We will be able to extrapolate about all life from this survey," Venter says. "This will put everything Darwin missed into context."

Emily Mullin

Steven Levy

Andy Greenberg

Jeremy White

For now, though, the expedition has run aground, snagged on an unanticipated political reef here in French-controlled waters. But it may all work out tomorrow. Right now, the sun is just beginning to soften toward sunset, and a gentle breeze is rustling the palms. Venter has disappeared in the direction of the boat, and one of his crew members, wearing a Sorcerer II T-shirt over her bathing suit, is waving me back. Must be close to dinnertime.

The last time I spent a few days with Venter on his yacht was in 2002 on St. Barts. He was in a much darker mood. He had just been fired as head of Celera Genomics and was hiding out in the Caribbean, licking his wounds. He had started the company four years before to prove that a technique called whole-genome shotgun sequencing could determine the identity and order of all DNA code in a human cell and do it much faster than the conventional method favored by the government-funded Human Genome Project. He had already made science history by using his technique to uncover the first genome of a bacterium, but most people doubted it would work on something as large and complicated as a human being. Undaunted, he pushed ahead, informing the leaders of the government program that they should just leave the human genome to him and sequence the mouse instead.

Venter also promised that he would give away the basic human code for free. Celera would make money by selling access to gobs of additional genomic information and the powerful bioinformatics software tools needed to interpret it. His critics claimed that he was trying to have it both ways, taking credit for providing the world with the code to human life and reaping profits for his shareholders at the same time. Venter cheerfully agreed.

Things didn’t quite go according to plan. His gambit did indeed accelerate the pace of human DNA sequencing, and the shotgun approach has now become the standard method of decoding genomes. But galled by the effrontery of Venter’s challenge, the Human Genome Project scientists closed ranks and ramped up their efforts quickly enough to offer a draft of the genome almost as fast as Celera’s nine-month sprint. In June 2000, the increasingly bitter race came to an end in a politically manufactured tie celebrated at the White House. The détente with the public-program scientists lasted about as long as it takes to pack up a camera crew. And by that summer, Celera, once king of the startup biotech sector, had already begun a long sad slide into the stock-price cellar and corporate obscurity. "My greatest success is that I managed to get hated by both worlds," Venter told me on St. Barts.

I didn’t see much of him after that. I was finishing a book about the genome race, during which he had given me access to Celera. But I had plenty of material by then and needed some distance from his inexhaustible, often exhausting ego. (As is true for many highly successful people, it was all about him.) I knew his funk would not last very long. Life was too short, and the thrill of accomplishment too powerful a drug for him. Using $100 million from Celera and other stock holdings, he started a nonprofit, the J. Craig Venter Science Foundation, that would free him to do any kind of science he wanted without obligation to an academic review panel or a corporate bottom line. In 2002, the foundation launched the Institute for Biological Energy Alternatives in Rockville, Maryland.

At the top of his to-do list: Create life from scratch, splicing artificial DNA sequences to build a functioning synthetic genome then inserting it into a cell. The ultimate goal would be to endow this man-made organism with the genes to perform some specific environmental task - gobble carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, say, or produce hydrogen for fuel cells. Last November, Venter announced that his IBEA team, led by Nobelist Hamilton Smith, had successfully constructed a functioning virus molecule out of 5,386 DNA base pairs in a mere two weeks. "Nothing short of amazing," said US secretary of energy Spencer Abraham, whose agency funded the work.

To me, the press conference hoopla had a tinny ring. Another team at SUNY Stony Brook had manufactured a larger virus a year earlier, albeit using a technique that had taken three years. But viral genomes are much smaller than those of truly living organisms - a mere few thousand base pairs, compared with hundreds of thousands in the smallest genome of a bacterium. Most scientists doubted that Venter and his colleagues, or anyone else, could build a genome that big from scratch and get it to work in a cell. Venter was saying he could do it in three to five years.

Venter resurfaced in the news early this year with a more substantial, if less sensational, announcement. By applying the whole-genome shotgun method to an entire ecosystem instead of to an individual genome, he had conducted a study of microbial diversity in the Sargasso Sea near Bermuda. Known to have a low concentration of nutrients, the Sargasso was also assumed to harbor relatively few microorganisms. But instead of an ocean desert, Venter found an abundant and varied soup of microbes wherever he sampled the seawater. In March, he announced that his Sargasso team had discovered at least 1,800 new species and more than 1.2 million new genes. Conservatively speaking, that doubled the number of genes previously known from all species in the world. This code was to be made available on GenBank, a public genetic database, for researchers everywhere to use with no strings attached. Included were almost 800 new genes involved in converting sunlight into cellular energy. As a kicker, Venter also revealed that the Sargasso trip was only a pilot project for a vastly more ambitious undertaking: His yacht the Sorcerer II was at that moment in the Galépagos Islands, embarked on a two-year, round-the-world expedition that promised to overwhelm the huge amount of data from the Sargasso Sea.

A few days later we were talking about how I might join him for a segment of the trip through French Polynesia. "I have this idea of trying to catalog all the genes on the planet," he said, matter-of-factly. I wasn’t sure what that meant - how can anybody find all the genes in the world? How would you use all that raw material when there was already more information in the world’s genetic databases than anyone knew what to do with? But I had never been to the South Pacific, and the names of the places where the boat planned to take samples - Hiva Oa, Takapoto, Fakarava - sounded like the tinkling of shells. I figured it was time to reconnect.

When I return to the Sorcerer II for dinner, Venter is dressed in the blue Speedo he’s been wearing most of the time I’ve been down here. He’s checking email on one of the boat’s five computers (not counting the litter of laptops in the main cabin). Charlie Howard, the Sorcerer II ’s captain, is relaxing on deck, as much as he ever relaxes. I remember him from St. Barts. In his previous life, Howard was an electrical engineer in Toronto. Then he decided to take a year off and sail to the Caribbean, and when the year was over he couldn’t think of a good reason to go back. He is 47 now and has been living on boats more or less his whole adult life. Venter can get off the boat anytime and fly back to the States to conduct business, then rejoin the crew later. If Howard were to leave, the expedition would stop.

We are on Rangiroa, the largest of many atolls in the Tuamotu Islands, 200 miles northeast of Tahiti. It consists of a low and thin broken ring of beach and vegetation surrounding a huge lagoon. Darwin sailed through the Tuamotus on the Beagle in 1835, marveling at how islands just barely above the sea managed not to be swept away by the ferocious Pacific. More than a half century earlier, Captain James Cook’s HMS Endeavour sighted land here after an open-water passage of 5,000 miles from Tierra del Fuego. "I’m in awe of Cook," Howard says. "Imagine sailing through these islands at night. Nothing but the sound of the surf to let you know you might be in trouble up ahead. That would be scary stuff."

Among those aboard the Endeavour was a young man named Joseph Banks, a member of the Royal Society and "a Gentleman of Large Fortune, well versed in Natural History," according to British Navy records. At 25, Banks was just a few years older than Darwin was when he made his voyage on the Beagle - eager, handsome, and by all accounts a very personable fellow. He got along particularly well with the native women he encountered during the Endeavour ’s subsequent languid stay in Tahiti.

Banks had paid-10,000 - the equivalent of about $1 million today - for the privilege of joining Cook’s expedition. His aim was to collect and describe every plant, animal, fish, and bird he could lay his hands on. Just three days out of Plymouth, England, he noted the presence of "a very minute sea Insect" in some water taken on board to season a cask. But most of Banks’ descriptions, like Darwin’s, were of the larger life-forms he shot from the sky, netted from the ocean, or uprooted from the ground. A decade earlier, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus had estimated the total number of plant and animal species on Earth to be no more than about 12,000; Banks and his team (including a student who had worked under Linnaeus) recorded some 2,500 new ones on the Endeavour ’s three-year voyage alone. On his return home, he was the toast of all England, adored by the press and a frequent visitor of the king.

Like Banks and Darwin, Venter believes his circumnavigation will greatly increase the number of known species. Of course, his methods and equipment are vastly more sophisticated. But the world he’s exploring is also much more obscure than the one they studied. Scientists estimate that the microbial species identified so far account for less than 1 percent of the total number on Earth. Even under a microscope, the simple shape of microorganisms - rods and spheres, for the most part - makes it difficult to use morphology to describe and classify them, as Banks and Darwin were able to do with the animals and plants they collected. Finally, most microbes do not reproduce sexually, but some do swap genes across species lines, confounding the very notion of "species" in this teeming context.

All this has led to a skewed view of Earth’s biodiversity. People think of insects as the most numerous organisms. Split open any single insect and hundreds of thousands of microbes will tumble out. Billions live in a handful of soil in your garden or in that gulp of seawater you coughed up at the beach last summer. Yet of the roughly 1.7 million plant and animal species so far named and described, only some 6,000 are microbes - all of which have been cultured. The true number out there may be closer to 10 million. Or perhaps 100 million. Nobody really knows. "Imagine if our entire understanding of biology was based on a visit to the zoo," says Norman Pace of the University of Colorado, Boulder. "That’s where we’ve been in microbiology."

Over the past 30 years, Pace has led a generation of microbiologists who use gene sequences instead of morphology and behavior to identify and classify species. This approach does not require culturing the bugs in a petri dish - you just isolate the right bit of DNA using standard molecular biology. Some "housekeeping" genes are so essential to the maintenance of life that they can be found throughout the living world with the order of their DNA letters more or less intact. But over time, small changes do crop up through harmless mutations. Thus, a very close match in the order of letters in such a gene implies a close relationship between two species; a less similar match, a more distant relationship. By combining all such comparisons, you can construct a whole phylogeny of the known microbial world. It is very much a work in progress. In 1987, the first such family tree, constructed by Carl Woese at the University of Illinois, identified 12 phylogenetic divisions. Now there are about 80.

One gene in particular, called 16S rRNA, has become a workhorse for identifying and classifying microbes. Every species, from the lowliest bacteria to humans, has one and only one 16S rRNA gene. Extract the DNA from some seawater or soil and count the number of different 16S genes, and you have at least a general idea of how many microbial species there are in the sample. Compare the DNA sequences of those genes, one to another, and you have a notion of their family relationships as well. Venter would have pleased the microbiologists by going to the Sargasso Sea and looking for 16S rRNA genes or zooming in on some other target. But zooming in is not his style. He likes to zoom out. "My theme has always been randomness and random sampling," Venter says. "Every time, people have said it was the wrong way to go about it. And every time, I’ve made major contributions."

Venter’s approach is to take all the DNA from all the microbes he found in the Sargasso Sea at any given location and smash it into bits. He then tries to assemble the pieces into complete genomes, applying the same whole-genome shotgun assembly method he relied on when he conquered the human genome. The computer algorithms he uses are in fact those developed at Celera, though somewhat more refined. The target, however, is very different: Instead of one huge genome, like a giant jigsaw puzzle, there are thousands of tiny puzzles, with no guide to tell which piece belongs in which puzzle.

The results from the Sargasso samples surprised Venter. Since the microbial population was so diverse, it was harder for the algorithms to figure out whose DNA was whose and to bundle the fragments neatly into whole genomes. It turned out that only two organisms’ genetic codes were represented in their entirety - far fewer than Venter had anticipated. The study also cast serious doubt on the whole idea of comparing 16S rRNA genes to determine the number of species in a sample. Two assembled sections occasionally contained identical 16S rRNA genes, but the stretches of DNA surrounding the genes would be much too divergent to lump both assemblies into one species. Venter’s study made it look like the 16S rRNA approach was analogous to classifying mammals by comparing just their noses. On the other hand, without a lot more sequences fed into the equation - prohibitively expensive because of the cost of running sequencers - the shotgun assembly approach wasn’t able to get a handle on the number of species, either. There appeared to be a minimum of 1,800, but there could be tens of thousands, depending on what assumptions the computational biologists on Venter’s team used. "What Craig did was like grabbing a cubic mile of Amazon rain forest and trying to sequence the whole thing," says Pace. "He shouldn’t be surprised that it was really complex. Anybody who would do that doesn’t have a good concept of a scientific question."

Venter might have answered his critics with a targeted follow-up study of the Sargasso Sea. Instead he decided to sequence the world. "There’s an infinite number of questions you could ask," he says. "We’re just trying to figure out who fucking lives out there."

The Sorcerer II expedition began last August in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Venter chose the departure point partly because another famous scientific expedition - the voyage of HMS Challenger - had visited Halifax in 1873, and partly, he concedes, because he had never sailed that far north and wanted to see what it was like. The Sorcerer II then headed to the Gulf of Maine, continuing down the coast to Narragansett Bay and Chesapeake Bay, passing Cape Hatteras, and cutting around Florida into the Gulf of Mexico, through the Panama Canal and south to the Cocos and Galépagos islands.

About every 200 miles, the crew has been taking water samples. Jeff Hoffman, aka Science Boy, oversees the work and doubles as a deckhand. He is 31, has an easy southern manner, and is all but done with a doctorate in microbiology from Lousiana State University. His long, pleasant face is made longer by a goatee that has been sprouting since the expedition got under way. While taking time off from his studies, he was just hanging out and skiing with buddies in Colorado when he got a job interview at IBEA. The fact that Hoffman was a competitive swimmer especially intrigued Venter, who had been one himself. Now Hoffman is sailing around the world. "My dad says I’m the only guy he knows who can fall in a pile of shit and come out smelling like roses," he says.

When sampling, Hoffman records the latitude and longitude of a site, along with temperature, salinity, pH, pressure, wind speed, and wave height. Seawater, usually from a depth of about 5 feet, is pumped into a large plastic barrel on board and piped through a cascade of filters mounted in gleaming stainless steel casings in the aft cockpit (see "How to Hunt Microbes," page 111). The filtering process takes up to five hours, including setup and cleanup; during downtime, Hoffman listens to his iPod or lifts weights.

When all the water has passed through, he carefully uses tweezers to remove the filters, then bags them. The bags are labeled, frozen, and periodically sent back to his colleagues in Rockville to be analyzed. Sometimes Hoffman scrawls a personal note on the label, like Send burritos or We’re out of Jack Daniels . The color of the used filter papers changes depending on what’s on them. The ocean is hardly one big homogeneous soup. Just by looking at these filters - some seem barely stained, others look like they’ve been dipped in pond scum - you can see there is a lot of variation in the microbial populations from one spot to another. The ones from Halifax Harbor look like they’ve been used for toilet paper, which in a sense they have, since Halifax is one of the largest harbors in the world without a comprehensive sewage treatment system.

Some of the most spectacular sampling came during two weeks in the Galépagos, islands that became famous for Darwin’s sojourn there, as well as for the varieties of finches, mockingbirds, tortoises, and marine iguanas that did so much to buttress Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Venter conceived of his expedition as following in Darwin’s footsteps, and now he was sailing into the same bays and trudging up the same rocky paths as the great man himself. He had organized the visit well ahead with scientists at the Charles Darwin Research Station on the island of Santa Cruz to ensure sampling in the most productive spots; these included several unusual environments, each likely to contain a unique spectrum of microbial life, with differing metabolic pathways and hence different sets of genes. In several locations, they took soil samples to supplement the water specimens.

Getting those samples from the top of Wolf Island was a separate adventure. It required four crew members to leap onto a sheer rock face from a dinghy surging on 7-foot-tall surf, while Howard fought to keep the boat from crashing into the cliff. They picked their way up the slope wherever they could find a foothold, navigating around the famously unafraid frigate birds and boobies and trying especially to avoid the babies pecking at their hands and feet. All this in roasting heat. "It was a pretty intense climb," Hoffman tells me. "We were all sweating our asses off." On the return trip, he and another climber flung themselves off the cliff face into the cool water 30 feet below.

Venter’s expedition also took samples from mangrove swamps, iguana nesting areas, and interior lakes. The team obtained a promising sample directly from a sulfur vent bubbling up from the seafloor off another chunk of rock called Roca Redonda. Venter and Brooke Dill, the expedition’s diving master, plunged 60 feet underwater with the sampling hose, struggling not to be swept away or battered against the rocks by the swirling currents. Sea lions danced overhead. To get a sample from a flamingo-dotted pond on the island of Floreana, Venter, Hoffman, and others lugged 13-gallon carboys over a hill to be loaded onto the boat. It was worth it. The 100-degree water was so full of life that the filters clogged up after only 3 gallons of water had passed through.

A week after my trip, I caught up with the Galépagos samples at IBEA in Rockville, where molecular biologist Cyndi Pfannkoch, who runs the DNA prep facility, took me through the extraction process. The filter papers are first cut into tiny pieces and placed into a buffer that cracks open the cell walls of the organisms, spilling their contents. Chemicals are added to chew up proteins and leave just the DNA, which is spun out of the solution. Pfannkoch pulled a vial from a rack and held it up to the light. "See that white glob down there?" she said. "That’s DNA from the flamingo pond. Compared to a typical sample, this is huge . I can’t wait to see what’s in it."

On our way out the door to visit the lab where the DNA is sequenced, Pfannkoch opened a huge freezer; stored inside at -112 degrees Fahrenheit were Hoffman’s labeled pouches. She took out a bag and rubbed the thick layer of frost off the label with a finger. In addition to the ID, it read: Panamanian women are hot .

When the boat was five days out from the Galépagos, a shrieking alarm warned that the engine was dangerously overheating. Howard rushed below and found that the belt driving the alternator and water pump had shredded. In preparation for just these incidents, he had squirreled away spare parts behind every floor and ceiling panel, and he replaced the belt easily. But a day later that one blew, too. Howard dug into the problem and discovered that a couple of ball bearings had self-destructed in the pulley holding the belt. That was one part with no spare. To make things worse, the ship was about to enter the Pacific doldrums, and it might have taken weeks to reach Polynesia under sail. "When you hear Charlie yelling, ’Oh, shit!’ that’s not good," Hoffman says. "The guy is MacGyver." Howard cursed some more, thought for a while, then rigged up a workaround by cannibalizing some bearings from a less crucial pulley. He wasn’t sure if it would hold 10 minutes or 10 hours. It’s a couple of weeks later now, and the engine is still running on the fix.

Then there are the political obstacles. Marine research is governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which outlines what one country must do when undertaking science in another’s territorial waters. If you’re talking about garden-variety oceanographic research, obtaining permission is usually easy. But the unprecedented scale of this genetic dredging project - We’re going to sequence everything we find! - would raise a few red flags even if its leader were not J. Craig Venter. And the obstacles are higher since many people are still certain that "Darth Venter" tried to privatize the human genome, allowing access to the code only to the deep pockets who could afford it.

This time around, he’s doing everything he can to convince the world that he has no commercial motive: Here, take it all, I ask for nothing in return. His generosity has actually exacerbated his political problems. By the nature of its research, the Sorcerer II expedition falls under the jurisdiction of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, which has established guidelines for "benefit sharing" of resources. In return for access to their waters, in other words, governments expect a piece of the action. But if - like Venter - you are giving everything away, you don’t have any benefits to share. "The irony is just too great," he says. "I’m getting attacked for putting data in the public domain."

The expedition has also come under assault by activists. On March 11, while the Sorcerer II was in the Galépagos, the Canada-based Action Group on Erosion, Technology, and Concentration issued a press release titled "Playing God in the Galépagos."

"J. Craig Venter, the genomics mogul and scientific wizard who recently created a unique living organism from scratch in a matter of days, is searching for pay dirt in biodiversity-rich marine environments around the world," it reads. While Venter might have promised not to patent the raw microbes he found, the environmentalists’ argument went, he or someone else could genetically modify them, then claim patents on the engineered life-forms. Whatever he was doing, the ETC Group saw it as an immediate international concern. The release also cited Accién Ecolégica, which accused Venter of pirating Ecuador’s resources, because his permits to export samples from the Galépagos were not properly authorized.

The day after the near-disaster with the alternator pulley, Venter was immediately notified by Rockville of a fax from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs politely informing him that his application to conduct research in French Polynesia was denied. The ministry understood that the Sorcerer II ’s mission was to collect and study microorganisms that might prove helpful for health and industry, but France wished to protect its "patrimony" by restricting "extraction of these resources by foreign vessels." "It’s French water, so I guess they’re French microbes," Venter told me when he got the news. (The Sorcerer II ’s communications technology is high-end for boats twice its size, and a phone call from the middle of the Pacific to my home in New Jersey was no big deal.)

He didn’t sound too worried. He had already enlisted the French ambassador to the US to lobby Paris on his behalf, and some top French scientists were writing letters of protest to the ministry. But when the Sorcerer II reached the French Polynesian island of Hiva Oa in the Marquesas archipelago, the port captain there informed Venter and Howard that their vessel was not allowed to leave the harbor. Impounding a private foreign vessel merely on suspicion is against international law, and Venter protested to the US State Department, which informed the ministry that it considered the act a violation of the honor of the United States. The Sorcerer II was allowed to proceed as a normal tourist vessel, but with a warning not to attempt to take any samples.

After three weeks, a formal convention was drawn up and signed by Venter and the French Polynesian administrator overseeing research. The president of French Polynesia would also need to sign the document, but this was a mere formality. Sampling could begin at any moment.

A few days later, I meet up with Venter at the InterContinental Beachcomber Resort in Papeete, the capital of French Polynesia. Decades of commercial and industrial growth have taken the paradise out of the Tahiti that Banks sailed into aboard the Endeavour back in 1769, but the InterContinental has trucked a little of it back in. The vibrant gardens beneath my balcony give way to an azure pool surrounded by a beach of pure, imported white sand, beyond which lies the lagoon. Half a mile out, the waves break on the reef. Nine miles away, the island of Moorea springs up from the sea, its jagged green peaks bundled in thunderclouds. After dinner, we take in the hotel’s Tahitian dance show. The women sway and wave their arms, and the men lunge about, slapping their arms and fluttering their knees and uttering sudden loud testosterone-fueled barks in unison. This is the otea - originally a war dance - and at times it seems the men are about to leap into their pirogues and invade Moorea. The next morning I notice that the bellhop loading our bags into the car looks familiar. He was one of the dancers.

By this point, the Sorcerer II has been released from its political shackles on Hiva Oa and has proceeded westward to the Tuamotus. We fly out to meet the boat at Rangiroa. As we come in for a landing, I can see it anchored just inside the lagoon, sleek and white, decks shining in the sun.

We are met at the airport by Howard and Juan Enriquez, a friend of Venter’s for about 10 years. In the early 1990s, Enriquez, whose mother is a Boston Cabot, was head of Mexico City’s Urban Development Corporation and deeply immersed in Mexican national politics. Since meeting Venter, he has become an enthusiastic teacher, writer, and promoter of genomic science and enterprise - a sort of freelance genomophile. He spent two years as a senior research fellow and founding director of the Life Science Project at Harvard Business School and is currently the CEO of Biotechonomy, a life sciences venture capital firm. He has been traveling with the expedition for more than a month. "I gave up a lot for this," Enriquez tells me as we motor out to the Sorcerer II in a dinghy. "I canceled a meeting with Bush and blew off a couple of foreign ministers. But what could be more exciting than sailing around the world, discovering thousands of new species?"

We’re greeted on deck by Hoffman and first mate/second engineer Cyrus Foote, both barefoot and stripped to the waist.

"We mooned the plane as you flew over," Hoffman tells Venter.

"I’m not sorry I missed that," he replies and goes below to confer with Howard and change into his blue Speedo.

I stay on deck and Enriquez gives his take on the permit issue. He’s philosophical about it, seeing it as part of the history of civilization. His theme is information. When humans invented cave art, they gained an enormous advantage over other animals because they were able to convey information about things that were not actually present. The next major step was the invention of Egyptian hieroglyphics, a way of standardizing information. Then came the much more efficient 26-letter alphabet, then, in the 1950s and ’60s, the two-letter alphabet of binary code. Now, he says, the four-letter code of the genetic script - A, C, T, and G - is driving another revolution. Through the application of genomics, an acre of land once used to produce food, feed, or fiber will be used to produce medicine out of plants, and microbes from the ocean will be recruited to make free energy.

This puts a whole new spin on things. "The world is going genomic," Enriquez says. "If you do not perceive the possibilities in this shift, if you say no instead of yes , you will be left in the past. There will be whole societies who end up serving mai tais on the beach because they don’t understand this." Including the French, unless they get their act together and allow the Sorcerer II and projects like it to go forward. "What you’re watching right now with the permit issue is almost a mirror image of what happened in the digital age," he says. "With Minitel, France had the Internet wired to every house 10 years before anybody else. But instead of having an entrepreneurial system that said yes, they had a closed system that said no, you can’t do this, you must use French software, we’ll tax your stock options. And now Finland is beating the shit out of France in the digital revolution."

While Enriquez goes to shore to arrange a diving expedition, Howard shows me around the boat, pointing out the changes that have been made to convert a luxury yacht into a research vessel that looks and feels pretty much like a luxury yacht. One of the most obvious adjustments is the lab bench set up in the library next to the galley; it includes a $35,000 fluorescent microscope hooked up to a 42-inch plasma videoscreen on the wall (also useful for watching movies). At 95 feet long, Howard says, the Sorcerer II is almost exactly the size of the Endeavour . But where Cook’s vessel was made of wood, hemp, and pine tar, Venter’s is fabricated from foam core, epoxy resin, and carbon fiber. The Sorcerer II ’s aerodynamic hull is essentially that of a modern racing yacht, while the Endeavour ’s was a "huge bulbous box with square ends," Howard says. Cook navigated by the stars and measured water depth with a knotted rope. Venter has bottom-imaging sonar and assorted other navigational aids, including digitized charts with GPS. We have 10 people on board, all of whom have a reasonable expectation of returning home alive. Of the 94 who left England aboard the Endeavour , some 40 died en route, including most of Banks’ retinue of artists, fellow naturalists, and servants.

Howard introduces me to the rest of the crew. Maybe it’s all the tanned flesh and tight stomachs, but they seem to radiate physical competence, moving fluidly about the deck as if they are genetically adapted to this microenvironment. Foote, the youngest at 26, has spent most of his life on the water, except for a stint as a graphic designer in Manhattan. A skilled sailor, he’s also an expert surfer and free diver. (On a recent dive, five sea urchin spines pierced his hand. He knew enough not to try to pull out the barbed spines, calmly pushing them through the other side of his hand instead.) Tess Sapia, the cook, has been working on boats in one capacity or another since leaving her native California; she has a captain’s license. Dill, the diving master, joined the Sorcerer II with Foote in Newport, Rhode Island, serving also as marine naturalist and deckhand. Stewardess and deckhand Wendy Ducker just joined the crew in the Galépagos. Years ago she worked as an advertising art director in San Francisco. But that was before her resort job in Zimbabwe, which involved skydiving, white-water rafting, safari walking, and bungee jumping off the Victoria Falls bridge. She then spent a couple of months backpacking through Brazil. She was learning to surf in the Dominican Republic when Howard contacted her about this job. "I wanted to do a circumnavigation and was looking for adventure," she tells me, as if she’d been sacking groceries up to that point.

When I wake up the next day, Venter is in the main cabin reading an email from his office; Howard leans over his shoulder. Dill is setting the table for breakfast. "So the big news this morning is your friends the French are going to send a gunboat out to escort us," he tells me. (I’m not quite sure why he calls them my friends, but it could have to do with an incident in a bar on St. Barts that I’d rather forget.) "They want to make sure we sample where we said we would. We’re not supposed to tell the State Department about this. It might put a chill on French-American relations. Being as how they’re so cozy right now and all," Dill says.

"They’d like to know if we’d like to invite an officer on board, too," Venter says. "How do you say ’fuck you’ in French?"

Everybody gathers, and Sapia serves breakfast: bacon, fruit, and "freedom toast." I sneak a peek at the email. It’s a bit less dramatic than Venter made out - for instance, it says vessel , not gunboat - but the gist is about right. All that’s needed to begin sampling is the president’s signature - except that the signed document then has to be faxed to Paris for confirmation, and Easter weekend is approaching, with Monday being a French holiday in short, sampling probably won’t start until Wednesday, or even Thursday - when I’m scheduled to go home.

The next morning, just off Rangiroa, I look around the edge of the lagoon we’re anchored in. I don’t see any gunboats.

"Why don’t we just take some samples and throw them away if permission doesn’t come through?" I ask Howard.

"Because if they caught us, they could impound the boat," he says. "Take the crew off. Cancel the expedition. This is serious stuff."

Nobody else seems impatient, least of all Venter, and gradually the sun and heat and breathless beauty of the place begin to blunt my own sense of urgency. Enriquez organizes an excursion to a nearby reef so rich with sea life they call it the Aquarium. The next day we drift-snorkel from the ocean to the lagoon. Sharks and fish abound. Over here’s a manta ray. Down there, a Napoleon wrasse, like a great rainbow-colored bus. Foote circles below me for two minutes at a time on a single breath of air. "He’s a marine animal," says Dill. Later, Enriquez and I take the dinghy into the sleepy town to get some food coloring to dye eggs for an Easter egg hunt. The shops don’t have any food coloring, or any eggs for that matter. I read Banks’ journal from the Endeavour . At night we watch movies on the big plasma screen. There’s a card game. Venter considers himself a whiz at hearts, which naturally makes me want to take him down. I lose. The day after Easter we motor over to a secluded lagoon on the other side of the island, where we snorkel some more, and Venter walks naked on the beach. Enriquez whips up his special "coco locos," which pack a punch. That night, somebody paints my toenails purple.

With all this lolling about, you’d think I’d at least be able to corner Venter. But a téte-é-téte - me with my notebook, him with his thoughts - keeps getting put off. Venter really wants to go diving. Sapia could use some help shucking coconuts for her marinade, and what have I done today to pitch in? Howard and Foote are going waveboarding, and, you know, this may be my last chance ever to try it. Three days disappear like magic. I try to explain to Venter that there’s a lot I don’t understand. How can you tell where one species ends and another begins? How do you even know what to call a species? What are you going to do with all the information you gather? What is the question being asked, other than, "Who’s fucking out there?"

"You gotta do your homework, Jamie," Venter says, slipping into his wet suit for another dive. "It’s all in the Sargasso Sea paper."

I retreat to my cabin with the copy I’ve brought along. It’s dense stuff. Searching for clarification on how species boundaries are determined, I find this: "From this set of well-sampled material, we were able to cluster and classify assemblies by organism; from the rare species in our sample, we use sequence similarity based methods together with computational gene finding to obtain both qualitative and quantitative estimates of genomic and functional diversity within this particular marine environment."

This is one of the easier sentences in the text. I put the paper aside and slip back into reading Banks. "I found also this day," he wrote on March 3, 1769, "a large Sepia cuttle fish laying on the water just dead but so pulld to peices by the birds that his Species could not be determind; only this I know that of him was made one of the best soups I ever eat."

Banks was writing more than 200 years ago, but I suspect that most of us are a lot closer to his understanding of what life means than to what Venter and his colleagues are writing about today. Part of the reason, of course, is the obscurity of the life they are exploring. Another reason is that this new approach to exploring biodiversity builds from the ground up, combining DNA sequences into genes, genes into inferred species, species into functional ecosystems. It’s no wonder that the language used to describe it is opaque to those of us accustomed to the birds and the bees and the flowers and the trees. Then there is the question of the sheer volume of data being generated. Banks found about 2,500 species, a graspable number. "Just between Halifax and the Galépagos, I wouldn’t be surprised if we find 10 million new genes," Venter tells me. "Maybe 20 million."

Always the big boast - but he’s probably right. Even Venter’s harshest critics have to acknowledge the astonishing amount of information, arguably more than anyone in history, he has generated about life. But how does all this information turn into knowledge ? What conceptual route leads from this tidal wave of data to an organizing idea, in the way that Darwin’s patient measuring of finch beaks and barnacle shapes gradually added up to the theory of natural selection? By the time the Sorcerer II circles the globe and the samples are sequenced and analyzed, Venter may indeed have "collected" 100,000 new species and tens of millions of new genes. Does he, or anyone else, possess the conceptual tools needed to pull some great truth out of such an ocean of information and vivify it like a bolt of lightning bringing Frankenstein’s monster to life?

This question is bouncing around in my head when we all go out to dinner on shore for our last night on Rangiroa. Permission to sample still hasn’t come through, and after a week of hanging out in this frustrating paradise it’s time to head back to Tahiti and home. The 10 of us are sitting at a long table under the stars in a little restaurant Enriquez has found. Venter is at one end of the table, and I’m at the other. Halfway through the meal, he says maybe this is a good time for that interview. It’s not as if there haven’t been plenty of chances to sit down without everybody else around, times when I haven’t had a couple of glasses of wine. I tell him I haven’t brought my notebook. Somebody helpfully rips open a paper bag and hands it to me to write on. Now I’m even more annoyed. But I start writing.

"The goal is to create the mother of all gene databases," Venter says. Let’s say you accomplish that goal, I reply. Is that enough for you personally? Banks set out to collect a lot of new species, and he succeeded. But he didn’t question the meaning of what he was collecting, the way Darwin did. Are we in an era now when just accumulating data is enough, or is there a question you’re trying to answer, an assumption you’re trying to test?

"There’s not one question, there are a million questions," he says.

"I think what Jamie’s asking is whether our expedition is like Charles Darwin’s or more like Joseph Banks’," says Foote. Exactly.

"Darwin didn’t walk around the Galépagos and come up with the theory of evolution," Venter says, a bit testily. "He was exploring, collecting, making observations. It wasn’t until he got back and went through the samples that he noticed the differences among them and put them in context."

Would you be satisfied, I ask, if all you did with this expedition was increase the number of genes and species known?

"If I could boost our understanding of the diversity of life by a couple orders of magnitude and be the first person to synthesize life? Yeah," Venter says. "I’d be happy, for a while."

It’s not a very enlightening answer, but I suppose asking someone, "Are you the next Darwin?" isn’t a very fair question. We leave the next afternoon, Venter at the helm as we head out of the passage from the lagoon to the open ocean. It starts to rain, and the seas build until they’re washing over the bow. Given his headlong "sequence now, ask questions later" approach to science, you might expect he’d be at least a little reckless as a sailor, but he’s supremely careful, monitoring the tension on every line, his eyes moving calmly from the sails and the gauges to the crew moving about the deck, watchful most of all for their safety. Once clear of the islands, we take watches through the night while the autopilot steers the boat toward Tahiti. With the roll and pitch of the boat, sleeping is impossible. I stumble up on deck early the next morning - "No standing upon legs without assistance of hands," Banks wrote in his journal on a day with swells like this. Venter is sitting alone in the cockpit, one hand on the helm, the other around a mug of coffee. "We’ve got a few minutes before breakfast," he says casually. "Why don’t we continue that conversation from the other night?"

I’d rather talk when I’m not holding on to the table to keep from falling over, but Tahiti looms off the bow, and I may not get another chance. It turns out that behind his glibness, Venter has actually thought a great deal about what might be called the data overload problem. He acknowledges that neither he nor anyone else yet knows what to make of the millions of gene sequences left in the Sorcerer II ’s wake. "How the hell can anyone work out the function of that many genes?" he says. "There aren’t enough biologists in the world, even if they work full-time on the problem for the rest of their lives."

Still, he says, just appreciating the true extent of the diversity of life on Earth is a major step, even if we have yet to understand which genes belong to which species and what role those genes play in the microbes’ lives. Venter uses astronomy as an analogy. Galileo could peer into a telescope and make inferences about the nature of the universe based on the motions of the stars and planets he observed. But it wasn’t until we understood the true immensity of space and could measure it against the speed of light that we could calculate back in time to the origins of the universe. With whole galaxies of genes to compare, Venter says, perhaps we’ll similarly be able to work back to understanding the origins of life. "Darwin was limited by what he could see with only his eyes, and look what he was able to accomplish," he says. "We want to use the minimal unit of the gene to look at evolution instead. People have been doing this with a dozen genes. We’ll have 10,000."

In the meantime, he imagines creating a Whole Earth Gene Catalog , complete with descriptions of every gene’s function. If you want to find the role of 100,000 genes, Venter says, the trick is to find a way of doing 100,000 experiments at once. All you would need that’s not already available is a synthetic genome, a sort of all-purpose template onto which you could attach any gene you wished, like inserting a blade onto a handle. You could then test the resulting concoction to see if it performed a specific vital task, such as metabolizing sugar or transporting energy. Using existing robotic technologies, you could do thousands of such experiments at once, in much the same way that a combinatorial chemist tests thousands of chemical compounds simultaneously to see if they have the desired effect on a target molecule. Most will not. But the ones that do can be investigated further. "I call it combinatorial genomics," Venter tells me. "It’s one of my better ideas if it works. In fact, it’s one of my better ideas if it doesn’t work."

Whether it works depends, of course, on Venter’s ability to construct a functioning synthetic genome. I ask how that project is coming along. The smallest genome known, that of the infectious bacterium Mycoplasma genitalium , is 100 times the size of the synthetic virus Venter’s team created. He acknowledges that the group is still a long way from being able to create a genome that big, much less getting it to function in a cell. So what they’re working on first is an artificial genome intermediate in size, between a virus and a bacterium. If they succeed, their creation will be unlike anything engineered in a lab.

"Would you call this thing alive?" I ask.

"It’s just a genome," he says. "But yeah, eventually we’ll put it in a cellular context. We’re going public with this by the end of the year. You’ll like it when you hear it."

With Venter, there must always be something new swelling on the horizon. Young Joseph Banks was content just to describe the new varieties of life he collected on his voyage. For him, this was a survey of God’s creation. Aboard the Beagle a half century later, Darwin was already questioning how the species he collected came to be. His ultimate answer wrested the helm from God and put it in the hands of natural processes instead. Now we’re sailing into a new evolutionary time, when we will have at least a finger on the tiller. Venter is hardly the only scientist leading us there, but he alone is taking the measure of life’s true diversity and dreaming up new life-forms at the same time. It’s not surprising that a lot of people, such as the activists who challenged him in the Galépagos, think he’s moving too fast, too heedlessly, into the future. But we can’t go backward. And nothing can be discovered by standing still.

Venter’s team takes samples from ecosystems around the world and sends them to his gene-sequencing HQ at the Institute for Biological Energy Alternatives in Rockville, Maryland. Here’s the way the microbes are snagged, bagged, and tagged.

Craig Venter’s Epic Voyage

How to Hunt Microbes

Joel Khalili

Nena Farrell

Chris Stokel-Walker

Aarian Marshall

Brenda Stolyar

The Voyage of Sorcerer II traces an expedition to unlock the genetic mysteries of the ocean

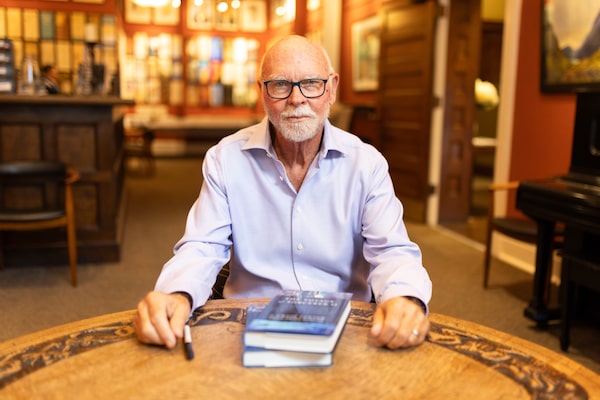

Scientist and author J. Craig Venter signs copies of his new book Sorcerer II: The Expedition That Unlocked the Secrets of the Ocean’s Microbiome at the Arts and Letters club in Toronto, on Oct. 26, 2023. Melissa Tait/The Globe and Mail

The expedition to crack open the ocean’s genetic treasure chest began in Halifax harbour under an overcast sky.

It was Aug. 20, 2003. J. Craig Venter, the geneticist turned entrepreneur, had arrived with the captain and crew of Sorcerer II, his 95-foot sailing yacht that doubled as a floating field laboratory. His mission: circumnavigate the globe while sampling the ocean waters along the way. It was to be a planet-wide DNA test that would shed light on the full breadth of the ocean’s genetic diversity in a way that had never been attempted before.

Venter was not a novice – to sailing or to mounting large and transformational science projects aimed at overturning the conventional wisdom of his peers.

“Everyone thinks that new discoveries are about making breakthroughs,” Venter told an audience during a recent visit to Toronto, where he sits on the science and innovation advisory committee for the Hospital for Sick Children. But often, discoveries simply overcome bad ideas of the past, he added.

Now 77, Venter was 56 and newly unemployed when he decided to travel around the world by sailboat. By then he was already a world renowned scientist and a notorious iconoclast. His innovative approach to genetic sequencing in the 1990s had allowed him to race the massive Human Genome Project mounted by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The effort reached its culmination in the summer of 2000 with the unveiling of a first draft of the full human genetic code three years ahead of schedule by the NIH and Celera Genomics, the company Venter co-founded in 1998.

The joint reveal, brokered by the White House, kept the focus on the future benefits of the achievement for humanity, but Venter has never been shy about saying he won the race. Eighteen months later he was fired from Celera because the leadership of the firm’s parent company “decided they didn’t need this radical scientist any more,” he said in an interview with The Globe and Mail.

What followed is documented in The Voyage of Sorcerer II, a book by Venter and his co-author, science writer David Ewing Duncan, that provides a personal account of a unique expedition.

For Venter it was to be the ultimate midlife reset – not to mention a chance to irk colleagues in academia and government who were locked into a more conventional approach.

It was “my best idea,” he said. “I found a way to sail around the world on my own boat and do science and get paid for it.”

It was also Venter’s golden opportunity to finally pursue science in a way that most excited him, as it was once done by Charles Darwin and other 19th-century pioneers: by looking and seeing what’s out there without any idea what might turn up.

Even the choice of Halifax as the expedition’s official starting was a kind of homage to this idea. Halifax had also been visited by HMS Challenger in 1873, the first expedition to survey life in the global ocean’s depths.

That historic voyage famously showed that the seafloor was not a biological desert sterilized by extreme conditions, as some thought at the time. No matter how deep, the ocean was occupied.

Venter frames his own voyage in similar terms, as showing that microbial life in the ocean is far more diverse at the genetic level than expected.

His first run at the idea came with a sailing trip in the spring of 2003 to sample waters in the Sargasso Sea, a portion of the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida where drifting micro-organisms are partly confined by currents.

A small team including expedition scientist Jeff Hoffman filtered some 400 litres of seawater to capture bacteria and then froze the contents for detailed analysis on land.

The results were obtained using the same “shotgun sequencing” technique that Venter had applied so successfully to the human genome. It starts with pulverizing DNA into short random strands that can be read by sequencing machines and then using a computer algorithm to match overlapping readouts from the fragments to reconstruct a complete genetic sequence.

But now, instead assembling the code of a single organism, the algorithm might be working with DNA from many separate bacterial species, invisible and indistinguishable from one another except through their genetic fingerprints.

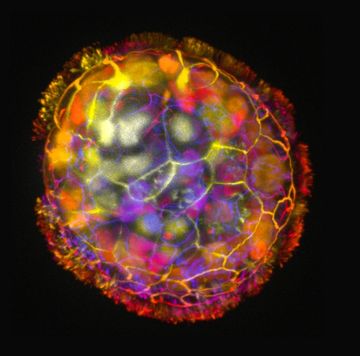

The result “blew our minds,” said Venter. The Sargasso Sea was teeming with diversity. As detailed in a research paper based on the analysis, the team found 1.2 million newly reported genes from at least 1,800 species including bacterial groups previously unknown to science.

It was an impressive haul but Venter was already working on a far more ambitious sailing trip to gather samples from around the world and show not only the vast richness of microscopic life in the seas but its variation from one location to the next. The uniform blue expanse that represents the ocean on a world map might, in reality, be subdivided into countless microbial domains, evidence of the dynamic multibillion-year evolutionary history of life on Earth.

By summer the expedition was coming together, drawing skepticism from some but also winning early support from some powerful allies, including Ari Patrinos, who was then director of biological research at the U.S. Department of Energy and key funder. Another supporter was the late E.O. Wilson, the celebrated Harvard University biologist.

“He liked that I was asking global questions and treating it as a much big picture,” Venter said.

The expedition’s first sample was collected in Halifax Harbour followed by a road trip by Venter, Hoffman and others across the width of Nova Scotia to scoop water out of the Bay of Fundy with the help of a local fisherman. The drive included a visit with Victor McKusick, the Johns Hopkins University professor known as the father of medical genetics, who had a summer home in the area.

The Sorcerer II soon headed back down the Atlantic coast, first to Hyannis, Mass., and then Annapolis, Md., for a final series of preparations that would allow the ship, under the guidance of Canadian-born Captain Charlie Howard, to travel the open ocean for months-long stretches without support.

In December the sailing and the sampling continued, with the ship making its way to Florida and on to the Caribbean and the Panama Canal. Venter’s initial plan had been to sail around South America but the time of year combined with the treacherous currents around Cape Horn ruled out a long journey around the continent. And there was the likelihood that Brazil would not permit sampling in its territorial waters – a harbinger of the growing debate over who holds sovereignty over genetics information obtained from the environment and any future profits that such information may generate. Although the expedition’s findings were always intended to be made public domain, Venter had already been branded “bio-pirate of the year” by one environmental group ahead of the voyage.

Sorcerer II entered the Pacific via the Panama Canal and onto the Galapagos Islands, following in Darwin’s footsteps but with the added complication of negotiations over permits and transport of samples back to the United States. The joy of exploring the biological wonderland shines through in Venter’s account, as he and his colleagues search for unique environments to sample, including a hydrothermal vent off Roca Redonda, a tiny steep-sided island that is the eroded remnant of an underwater volcano.

From the Galapagos the crew travelled west across the South Pacific, sampling the waters roughly every 200 miles.

“That’s roughly how far you can sail in 24 hours in a decent-size sailboat,” Venter said. “And so we’d stop once a day and take a sample.”

What the scientists on Sorcerer II found was that, at each stop, more than 80 per cent of the genetic sequences was “totally new and unique,” Venter added. The ocean was, as he had guessed, a far more complicated and genetically diverse patchwork of microscopic ecosystems than had once been supposed.

Other adventures were to follow, including an encounter with a SWAT team in Brisbane, which had been called to investigate whether the ship was a floating meth lab – apparently the work of a jilted fiancé whose former partner had become romantically involved with one of the crew. Later, some of the tensest moments of the voyage came during a stop at the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean where the crew had their passports seized by the British military, who threatened to impound the Sorcerer II until Venter was able to reach the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom by satellite phone.

The circumnavigation was completed in January, 2006, when the ship reached Palm Beach, Fla., nearly two and half years after departing Halifax. But it was only to be the beginning of a more sustained campaign of ocean sampling that would next take the ship up the Pacific Coast to Alaska and then on a trip through European waters from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Further excursions to Antarctica and the North Atlantic followed as the sampling work continued until 2018.

The final section of the book details the research results that have issued from the work, including insights into the active role that viruses play as managers of the marine ecosystem with implications for how nutrients cycle through the oceans.

The most significant impact of Sorcerer II’s voyage may be that it signalled the coming of age of metagenomics, the now widely employed technique of sampling the environment rather than organisms directly to understand the biology of the planet. It is an approach that has seen the merge of a revolution in genetics with big data and computational tools.

Despite Venter’s reputation as a pioneer in the use of algorithms to advance genomics, he takes a measured view of the role that AI will play in biology’s next chapter. Algorithms are tools that are only as good as the data they are trained on, he said. Ultimately it’s the mind of the scientist, and the spirit of discovery that gives direction and meaning to the scientific process.

For all its power, he added, AI “can’t answer questions about the unknown.”

Report an error

Editorial code of conduct

Follow related authors and topics

Authors and topics you follow will be added to your personal news feed in Following .

Interact with The Globe

- Science & Math

- Biological Sciences

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $23.30 $23.30 FREE delivery: Thursday, March 28 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $18.77

Other sellers on amazon.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Voyage of Sorcerer II: The Expedition That Unlocked the Secrets of the Ocean’s Microbiome Hardcover – September 12, 2023

Purchase options and add-ons.

“Will undoubtedly shape our understanding of the global ecosystem for decades to come.” ―Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of The Emperor of All Maladies A celebrated genome scientist sails around the world, collecting tens of millions of marine microbes and revolutionizing our understanding of the microbiome that sustains us. Upon completing his historic work on the Human Genome Project, J. Craig Venter declared that he would sequence the genetic code of all life on earth. Thus began a fifteen-year quest to collect DNA from the world’s oldest and most abundant form of life: microbes. Boarding the Sorcerer II , a 100-foot sailboat turned research vessel, Venter traveled over 65,000 miles around the globe to sample ocean water and the microscopic life within. In The Voyage of Sorcerer II , Venter and science writer David Ewing Duncan tell the remarkable story of these expeditions and of the momentous discoveries that ensued―of plant-like bacteria that get their energy from the sun, proteins that metabolize vast amounts of hydrogen, and microbes whose genes shield them from ultraviolet light. The result was a massive library of millions of unknown genes, thousands of unseen protein families, and new lineages of bacteria that revealed the unimaginable complexity of life on earth. Yet despite this exquisite diversity, Venter encountered sobering reminders of how human activity is disturbing the delicate microbial ecosystem that nurtures life on earth. In the face of unprecedented climate change, Venter and Duncan show how we can harness the microbial genome to develop alternative sources of energy, food, and medicine that might ultimately avert our destruction. A captivating story of exploration and discovery, The Voyage of Sorcerer II restores microbes to their rightful place as crucial partners in our evolutionary past and guides to our future.

- Print length 336 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press

- Publication date September 12, 2023

- Dimensions 5.7 x 1.3 x 8.3 inches

- ISBN-10 0674246470

- ISBN-13 978-0674246478

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

From the Publisher

Editorial reviews, about the author, product details.

- Publisher : Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press (September 12, 2023)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 336 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0674246470

- ISBN-13 : 978-0674246478

- Item Weight : 1.2 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.7 x 1.3 x 8.3 inches

- #27 in Biotechnology (Books)

- #92 in Genetics (Books)

- #271 in Environmental Science (Books)

About the author

J. craig venter.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top review from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

The Future does not Arrive Suddenly: Why we Need Visioners

Poetic reason as the creative center in maría zambrano, openmind books, scientific anniversaries, thousands of biological clocks keep time in the human body, featured author, latest book, craig venter, the man who knew himself.