aBlogtoWatch Monthly Giveaway

Win: Bausele Royal Australian Air Force Centenary 2021

Hands-On: Rolex Yacht-Master 42 Watch Reference 226627 In RLX Titanium

The visceral experience of wearing the Yacht-Master 42 titanium is very odd for any long-time Rolex fan. Rolex more or less helped create the 20th-century notion that you can often measure the value of a watch by feeling how solid and weighty it is. Rolex watches have never been designed for lightness, so most of them are quite hefty, and beloved for that reason. It is common for someone to admire a precious metal Rolex simply by feeling its mass in the open palm of your hand.

The Rolex Yacht-Master 42 was introduced in 2019 with tones very similar to this titanium model, but rather in 18k white gold and on a black Rolex Oysterflex strap. A yellow gold version was eventually added, and it seemed as though Rolex’s largest Yacht-Master was destined to be a precious-metal-only product. The 2023 226627 Yacht-Master 42 changes that paradigm by adding in a full grade 5 titanium case and matching bracelet to the product family. This is what people should consider the first “wearable” Rolex watch produced from titanium.

Even though Rolex uses the same grade 5 titanium as other brands, it focuses a lot on surface finishing and polishing for this timepiece. Rolex uses a sort of deep-grain engraving, which is somewhat different from the same effect on steel. Titanium as a color is also a bit darker than the comparatively bright 904L steel that most other (non-precious metal) Rolex sport watches are made out of. Titanium does scratch, and I asked Rolex about the service plan for the Yacht-Master 42 in RLX titanium. To make a long story short, Rolex will offer the same “case refresh” service for its titanium watches as it does for its steel and gold watches, though in reality, Rolex will have to use some special processes to polish titanium so that it looks fresh and new again. “RLX titanium” is really just Rolex’s way of indicating that it polishes and finishes titanium metal differently from other brands (according to Rolex).

Other than being in titanium with the matching bracelet, there isn’t too much new here. The Yacht-Master 42 case is 42mm-wide and has similar proportions as other watches in the larger Oyster Perpetual watch. The case is water resistant to 100 meters, and around the dial is a uni-directional rotating bezel with a matte-black ceramic insert that matches the matte-dark-gray tone of the Yacht-Master 42 dial.

Inside the watch is the Rolex in-house-made caliber 3235 automatic movement that operates at 4Hz with about 70 hours of power reserve. The movement offers the time with date and on the sapphire crystal is a Rolex “cyclops” magnifier lens. Titanium is considered by many engineers to be the perfect material for wristwatch cases. While I don’t think it is possible to ever determine “bests” in regard to an emotional product, it is true that you can easily enjoy the Yacht-Master 42 in titanium from purely a tool watch perspective. The lighter weight and large size give this 42mm-wide Rolex an interesting and desirable personality. It also makes us wonder whether or not there will be more titanium Rolex watches in the future. Possibly some, but I don’t think that Rolex, primarily a maker of conspicuous jewelry-style watches, will heavily focus on a material that will not hold a high polish as nicely as steel, gold, or platinum watches.

For watch lovers and Rolex collectors, there really is a lot of novelty to wearing a Rolex watch in titanium simply because most people haven’t ever done so before. The sister brand Tudor has had the Pelagos, which, for a while, was really the more sober equivalent of this Rolex Yacht-Master 42 226627. It is also much less expensive, but it doesn’t have the iconic Oyster Perpetual case shape and the famous Submariner-style dial that this Yacht-Master does.

While the Yacht-Master 42 in RLX titanium raises a lot of interesting philosophical questions about what Rolex should and shouldn’t be doing, the product will be a commercial success given the current latent demand for high-end titanium sport watches and anything even remotely interesting from Rolex. Rolex has made it clear that production of the titanium Yacht-Master 42 is going to be limited in scope, in large part because there are so many pieces of titanium in the case, and especially the bracelet, that all need to bear precisely matching polishes and finishes. I don’t imagine that this watch is easy for Rolex to make, but we do know that Rolex could increase production of titanium watches if it ever wanted to. Price for the very interesting and comfortable reference 226627 Rolex Yacht-Master 42 in RLX titanium is $14,050 USD . Learn more at the Rolex watches website here .

- Skip to content

- Skip to footer

- Français

Yacht-Master

THE WATCH OF THE OPEN SEAS

The Oyster Perpetual Yacht-Master, the emblematic nautical watch, embodies the privileged ties between Rolex and the world of sailing that stretch back to the 1950s.

Launched in 1992, the Yacht-Master was designed specifically for navigators and skippers. Embodying the rich heritage that has bound Rolex and the world of sailing since the 1950s, this Professional-category watch provides a perfect blend of functionality and nautical style, making it equally at home on and off the water.

AN IMMEDIATELY RECOGNIZABLE BEZEL

The Yacht-Master is easily recognized by its bidirectional rotatable 60-minute graduated bezel made entirely from precious metal (gold or platinum) or fitted with a Cerachrom insert in high-technology ceramic. The raised polished graduations and numerals stand out clearly against a matt background. This characteristic and functional bezel – which enables the wearer to read time intervals, for example, the sailing time between two buoys – plays a full part in creating the unique visual identity of the watch. The bezel can be turned with ease thanks to its knurled edge, which offers excellent grip.

CHROMALIGHT DISPLAY

The Yacht-Master offers great legibility in all circumstances, even in the dark, thanks to its Chromalight display: the large hour markers and broad hands are filled or coated with a luminescent material emitting a long-lasting blue glow – for up to two times longer than traditional phosphorescent materials .

THE YACHT-MASTER, SUPERLATIVE CHRONOMETER CERTIFIED

Like all Rolex watches, the Yacht-Master is covered by the Superlative Chronometer certification redefined by Rolex in 2015. This exclusive designation attests that every watch leaving the brand’s workshops has successfully undergone a series of tests conducted by Rolex in its own laboratories and according to its own criteria. These certification tests apply to the fully assembled watch, after casing the movement, guaranteeing superlative performance on the wrist in terms of precision, power reserve, waterproofness and self-winding. The Superlative Chronometer status is symbolized by the green seal that comes with every Rolex watch and is coupled with an international five-year guarantee.

The precision of every movement – officially certified as a chronometer by the Swiss Official Chronometer Testing Institute (COSC) – is tested a second time by Rolex after being cased, to ensure that it meets criteria that are far stricter than those of the official certification. The precision of a Rolex Superlative Chronometer is of the order of −2/+2 seconds per day – the rate deviation tolerated by the brand for a finished watch is significantly smaller than that accepted by COSC for official certification of the movement alone.

The Superlative Chronometer certification testing is carried out after casing using state-of-the-art equipment specially developed by Rolex and according to an exclusive protocol that simulates the conditions in which a watch is actually worn and more closely represents real-life experience. The entirely automated series of tests also checks the waterproofness, the self-winding capacity and the power reserve of 100 per cent of Rolex watches. These tests systematically complement the qualification testing during development and production, in order to ensure the watches’ reliability, robustness, and resistance to strong magnetic fields and to shocks.

THE OYSTER CASE, SYMBOL OF WATERPROOFNESS

The Yacht-Master’s Oyster case, 37 mm, 40 mm, or 42 mm in diameter and guaranteed waterproof to a depth of 100 metres (330 feet), is a paragon of robustness and reliability. The middle case is crafted from a solid block of Oystersteel, RLX titanium or 18 ct gold. The case back, edged with fine fluting, is hermetically screwed down with a special tool that allows only certified Rolex watchmakers to access the movement. The Triplock winding crown – fitted with a triple waterproofness system – screws down securely against the case. It is protected by an integral crown guard. The crystal, with a Cyclops lens at 3 o’clock for easy reading of the date, is made of virtually scratchproof sapphire and benefits from an anti-reflective coating. The waterproof Oyster case provides optimal protection for the movement it houses.

PERPETUAL CALIBRES 2236 AND 3235

Yacht-Master models are equipped with calibre 2236 (Yacht-Master 37) or calibre 3235 (Yacht-Master 40 and Yacht-Master 42), self-winding mechanical movements entirely developed and manufactured by Rolex. Consummate demonstrations of technology, these movements carry a number of patents. They offer outstanding performance, particularly in terms of precision, power reserve, convenience and reliability.

Calibre 2236 is fitted with the patented Syloxi hairspring in silicon, manufactured by the brand. In addition to resisting strong magnetic fields, this hairspring offers great stability in the face of temperature variations as well as high resistance to shocks. Its geometry, which is also patented, ensures the movement’s regularity in any position. Calibre 2236 includes a paramagnetic nickel-phosphorus escape wheel.

Calibre 3235 incorporates the patented Chronergy escapement, made of nickel-phosphorus, which combines high energy efficiency with great dependability and is also resistant to strong magnetic fields. This movement is fitted with the blue Parachrom hairspring, manufactured by Rolex in a paramagnetic alloy. In addition to resisting strong magnetic fields, this hairspring offers great stability in the face of temperature variations as well as high resistance to shocks. It is equipped with a Rolex overcoil, ensuring the calibre’s regularity in any position.

The oscillator of these two calibres has a balance wheel with variable inertia regulated extremely precisely via gold Microstella nuts. It is held firmly in place by a height-adjustable traversing bridge enabling very stable positioning to increase shock resistance. The oscillator is also mounted on the Rolex-designed, patented high-performance Paraflex shock absorbers, further enhancing the movements’ shock resistance.

Calibre 2236 and calibre 3235 are equipped with a self-winding system via a Perpetual rotor, which ensures continuous winding of the mainspring by harnessing the movements of the wrist to provide constant energy. Calibre 2236 offers a power reserve of approximately 55 hours, while the power reserve of calibre 3235 extends to approximately 70 hours thanks to its barrel architecture and the escapement’s superior efficiency; moreover, from 2023, its oscillating weight is fitted with an optimized ball bearing.

The Yacht-Master’s movements will be seen only by certified Rolex watchmakers, yet they are beautifully finished and decorated in keeping with the brand’s uncompromising quality standards.

BRACELET AND CLASP: SECURE AND COMFORTABLE

The Rolesium versions (combining Oystersteel and platinum) and the Everose Rolesor versions (combining Oystersteel and Everose gold) of the Yacht-Master 37 and the Yacht-Master 40, as well as the Yacht-Master 42 in RLX titanium, are fitted on a three-piece link Oyster bracelet, equipped with the Easylink comfort extension link. This system, developed by Rolex, allows the wearer to easily increase the bracelet length by approximately 5 mm, for additional comfort in any circumstance. On the Yacht-Master 42 in RLX titanium, the bracelet includes ceramic inserts – designed by Rolex and patented – inside the links to enhance its flexibility and longevity.

The Yacht-Master 37 and Yacht-Master 40 in 18 ct Everose gold, as well as the Yacht-Master 42 in 18 ct yellow or white gold, are fitted on an Oysterflex bracelet equipped with the Rolex Glidelock extension system. This innovative bracelet, developed by Rolex and patented, singularly combines the robustness and reliability of a metal bracelet with the suppleness, comfort and aesthetics of an elastomer strap. It is composed of two flexible, curved metal blades – one for each bracelet section – overmoulded with high-performance black elastomer. Developed by the brand and patented, the Rolex Glidelock is an inventive mechanism comprising a rack located under the clasp cover that enables fine adjustment of the bracelet length, without the use of tools. The Rolex Glidelock on the Oysterflex bracelet has six notches of approximately 2.5 mm each, allowing the bracelet length to be adjusted easily, up to some 15 mm.

The Oyster and Oysterflex bracelets on the Yacht Master models are equipped with an Oysterlock safety clasp, designed by Rolex and patented, which prevents accidental opening.

Related content

Yacht-Master II

Sea-Dweller

Yacht-Master

Made for sailing

The waterproof and robust qualities of this model make it the ideal watch for water sports and sailing in particular.

Exceptional legibility

Like all Rolex Professional watches, the Yacht-Master offers exceptional legibility in all circumstances, even in the dark thanks to its Chromalight display. The broad hands and hour markers in simple shapes – triangle, circle, rectangle – are filled with a luminescent material emitting a long-lasting glow.

The Yacht-Master 37 and Yacht-Master 40 are the only two models in the Rolex catalogue offered in Rolesium versions: the bezel is fashioned from platinum while the rest of the watch is in Oystersteel. These versions also harbour a turquoise- or red-lacquer seconds hand echoing the colour of the Yacht-Master inscription on the dial.

18 ct Everose gold

This exclusive 18 ct pink gold alloy – created and cast by Rolex – features a slightly stronger colour than traditional pink gold and exhibits subtle cool tones. Its sophisticated and contemporary colour resonates particularly well on watches that combine gold and Oystersteel, known as Rolesor versions (a combination of Oystersteel and gold).

Cerachrom bezel insert

The matt black monobloc Cerachrom bezel insert of the Yacht-Master is made of an extremely hard, virtually scratchproof ceramic whose colour is unaffected by ultraviolet rays, seawater or water that is chlorinated. In addition, thanks to its chemical composition, the high-tech ceramic is inert and cannot corrode. The numerals and inscriptions are moulded in the ceramic and coloured with gold or platinum using a PVD (Physical Vapour Deposition) process.

Bracelets and clasps

The Yacht-Master’s 60-minute graduated bezel is made entirely from precious metals or fitted with a Cerachrom insert in high-tech ceramic.

Calibres 3235 and 2236 Superlative movements

Shop New Arrivals

Rolex Yacht-Master Ultimate Buying Guide

As Rolex’s most diverse sports watch collection, the Yacht-Master is not only available in a wide assortment of case metals and sizes but it has also been paired with various bracelet styles and bezel materials. In less than three decades, the Rolex Yacht-Master collection has been home to dozens of references – some of which have been discontinued – and the nautical-inspired sports watch continues to be a mainstay of the Rolex lineup. There are two distinct models that share almost identical names: the Yacht Master and the Yacht Master II.

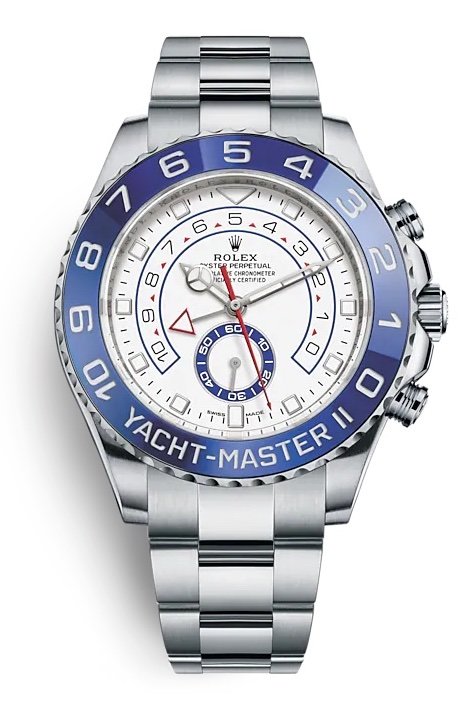

While the original Rolex Yacht-Master is an ultra-luxurious take on Rolex’s already popular sports watches, the Rolex Yacht-Master II was purpose-built to time out regattas in competitive sailing. Essentially, the Yacht-Master is the kind of watch you wear while lounging on a boat and a Yacht Master II is what you wear if you’re racing one. Nonetheless, both Rolex watches are incredibly popular, sought-after for their sleek designs and impeccable quality.

With that in mind, if you’re in the market for a Rolex Yacht Master, there are some important things you should know about the model (such as its history, pricing, and features) before you make a decision. Here, we’ve compiled everything you need to know about buying Yacht-Master and Yacht-Master II watches to make the most informed purchase possible. Ready to get started?

Rolex Yacht-Master

Yacht-Master Key Features:

– Case Size: 29mm, 35mm, 37mm, 40mm, 42mm – Material Options: Rolesium, Yellow Rolesor, Everose Rolesor, 18k Yellow Gold, 18k Everose Gold, 18k White Gold – Functions: Time with running seconds, date display. – Bezel: 60-minute timing (bi-directional) – Water Resistance: 100 meteres / 330 feet. – Strap/Bracelet: Oyster bracelet, Oysterflex bracelet

Click here to learn more about Rolesium: a special metal combination that is only featured on the Rolex Yacht-Master.

Rolex Yacht-Master II

Yacht-Master II Key Features:

– Case Size: 44mm – Material Options: Stainless steel, Everose Rolesor, 18k Yellow Gold, 18k White Gold – Functions: Time with running seconds, adjustable countdown timer with mechanical memory – Bezel: Ring Command Bezel – Water Resistance: 100 meters / 330 feet. – Strap/Bracelet: Oyster bracelet

Click here to learn how to set the adjustable countdown timer on the Rolex Yacht-Master II.

Quick Look: Rolex Yacht-Master Timeline

Even though the Yachtmaster collection is one of the newest additions to the Rolex lineup, there has been a great amount of innovation over the years. Additionally, while we didn’t see this watch come to life until the early 1990s, Rolex history shows that they had concepts and ideas of a yacht-themed watch long before it was ever brought to market. 1950’s — Rolex joins the prestigious New York Yacht Club 1966 to 1967 — Sir Francis Chichester becomes the first man to circumnavigate the globe single-handedly and he wore a Rolex Oyster watch 1992 — Rolex introduces the Yacht-Master collection 1994 — Rolex introduces the midsize and ladies’ models 1996 — Rolex introduces the two-tone midsize and ladies’ models 1997 — Rolex releases the Rolesium version (also known as steel and platinum) 2007 — Rolex releases the Yacht-Master II, which is the world’s first watch equipped with a programmable countdown timer and a mechanical memory 2013 — Rolex updates the movement inside the Yacht-Master II collection from the Cal. 4160 to the Cal. 4161. 2019 — Rolex introduces the Yacht-Master 42 to the collection

History of the Rolex Yacht-Master

While we wouldn’t be introduced to the very first Yacht-Master until 1992, Rolex’s history with sailing actually dates back to 1958, the year the Swiss watchmaker partnered with the prestigious New York Yacht Club. By then, Rolex had already garnered a reputation for making great waterproof watches with the invention of their Rolex Oyster case back in 1926. So, the partnership was actually quite a natural next step.

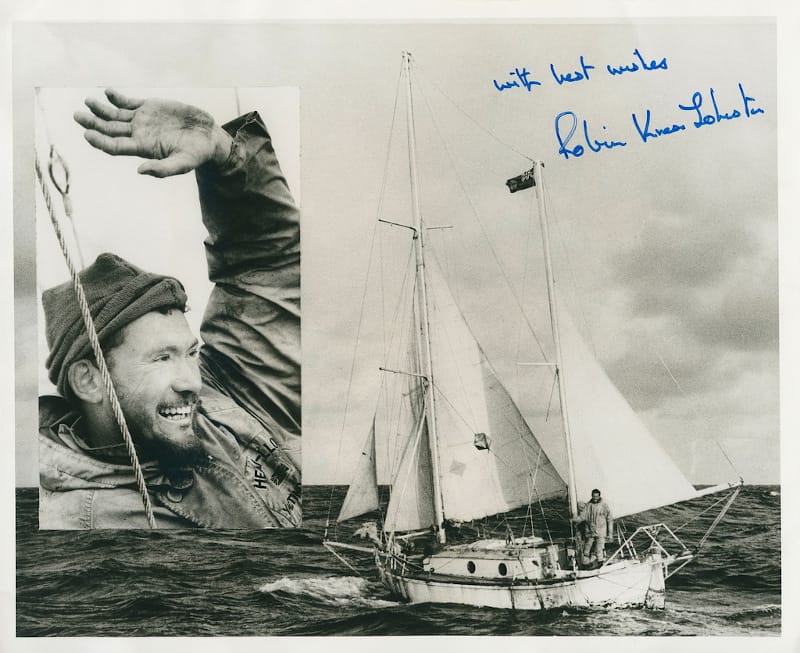

Rolex solidified its relationship with the world of sailing in 1966 when Francis Chichester — one of history’s most exceptional navigators — became the first person to sail around the globe on his yacht, the Gipsy Moth IV, with a Rolex on his wrist. His voyage, which spanned from August 1966 to May 1967, took him 29,600 miles around the world. however, the most impressive part is that he only had a few tools to help him navigate his way, including nautical charts, a sextant, and a Rolex Oyster Perpetual. The Rolex wristwatch chronometer he used was a reliable and steady partner, helping him keep time amidst rough conditions for 226 days at sea.

Despite the brand’s massive success in creating watches that were great for sailing, Rolex continued to hold back its efforts to create a watch specifically for this category. The brand did briefly dabble with the idea in the 1960’s, releasing a prototype dial for the Cosmograph chronograph with the name “Yacht Master” on it, but the idea never took hold. Today, only two known examples of this prototype Daytona Yacht-Master are known to exist — one belonging to Eric Clapton (whose model sold for $125,100 at auction in 2003) and one owned by legendary Rolex collector John Goldberger.

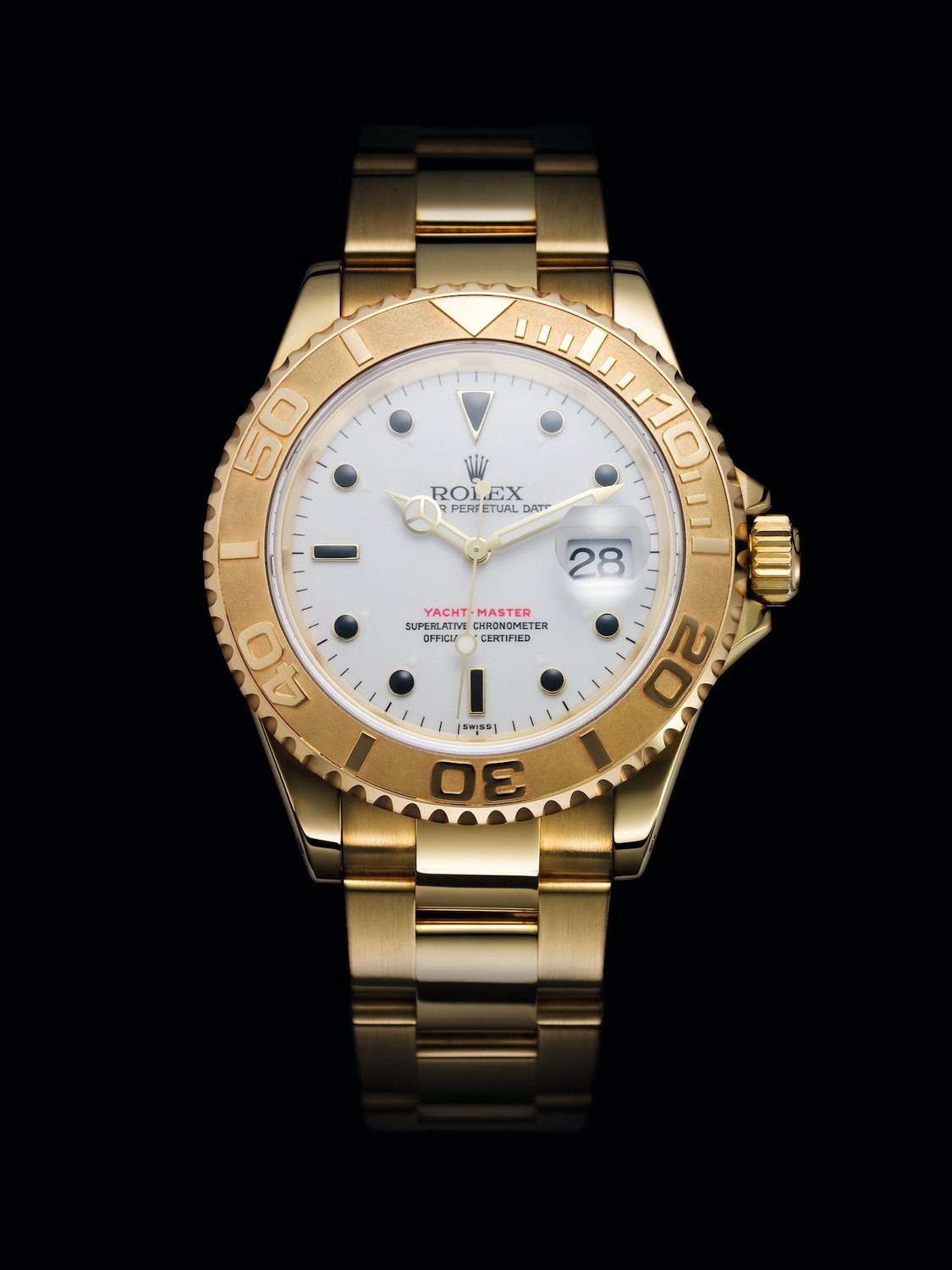

In 1992, we were finally introduced to the modern Yacht Master we know and love today. Its official name, the Rolex Oyster Perpetual Yacht-Master, was the brand’s first ultra-luxury sports watch built for the open seas. To make sure that collectors understood the luxury aspect of this new watch, the very first 40mm model was forged entirely out of solid 18k yellow gold and featured a matching gold bi-directional rotating bezel (marked to 60 minutes for timing) alongside a gold Oyster bracelet. Over the next few decades, Rolex has expanded the collection using a variety of materials as well as adding new sizes to the luxury nautical watch collection.

15 years after the first release of the Yachtmaster, Rolex introduced the regatta chronograph Yacht-Master II specifically made for sportsmen to use while regatta racing. To cater specifically to these athletes, Rolex outfitted the watch with important features like a programmable countdown timer (to measure with reliability how much time until the start of the race) and both flyback and fly-forward functionality (for easy synchronization should the race committee have to restart the race sequence). Another key difference is that the Rolex Yacht-Master II is only available in one size, 44mm with an Oyster case and bracelet. However, there are a variety of alloys available.

How Much is a Rolex Yacht-Master?

Because there is such a wide variety of sizes and materials used across the Rolex Yacht-Master collection, the prices tend to vary significantly. For example, you can pick up some of the older or smaller Rolex Yacht-Master models for around $5,000 on the second-hand market. However, newer, larger Yacht-Master models, especially those forged out of precious metals, can sell for well into five-figures.

How much is a Yacht Master II?

Due to its large size, complicated movement, and frequent use of precious metals, the Yacht-Master II is one of the higher-priced Rolex watches you can purchase. In terms of pre-owned prices, a stainless steel reference of the Yacht-Master II starts around $15,000. This may seem steep, considering that this Yacht-Master II is stainless steel and doesn’t feature any diamonds or gems. However, the complexity of the movement is what really makes this watch shine and it is the primary factor behind its high price tag. On the higher end, the yellow gold ref. 116688 costs $43,550 retail and can be bought for around $28,000 on the pre-owned market.

Buying Pre-Owned vs New Yacht-Master Watches

The key difference between buying a pre-owned Rolex Yacht-Master or Yacht-Master II versus a new one is the price. For a retail Rolex model , you will surely pay a premium – especially if you choose one of the precious metal models. On the secondary market, you can get a Yacht-Master for a much lower price, and many collectors find this option a better value for their investment. However, this is still totally dependent on the specifics about the watch which you can get an idea of in the chart above. The price of a pre-owned Yacht-Master will always vary depending on factors like its alloy, the year it was produced, condition, and whether it is a luxury-oriented Yacht-Master or a sporty and purpose-built Yacht-Master II.

Often, many collectors turn to the second-hand market to purchase a Rolex Yacht-Master. Of course, the price is a big factor, but due to the durability and overall build quality, a used Rolex Yacht-Master represents a highly competitive offering. Because these watches are purpose-built to withstand weather and water, they tend to age well even if they have been heavily worn, loved, and used. Another reason that collectors turn to the second-hand market is to get their hands on early models. Since the Yacht-Master has only been around for about 30 years, it is still quite easy to track down some of the early references. This is a great opportunity for collectors who not only love the Yacht-Master as a watch but who also want to make a smart investment for their collection that has great potential to increase in value.

Rolex Yacht-Master References

While the Yacht-Master is one of the newest Rolex models, only first introduced in 1992, the watch has been given a wide variety of upgrades in sizing, alloys, and bezels over the years. Here, this comprehensive list outlines all of the standard-production Yacht-Master references since its initial introduction. This list is also incredibly important as a reference if you are purchasing a Rolex Yacht-Master on the secondary market, as it will serve as a great quick reference for what models have been produced over the years.

Yacht-Master

226659 = 42mm, solid 18k white gold with Cerachrom bezel 16622 = 40mm; Rolesium (stainless steel and platinum) 16628 = 40mm; solid 18k yellow gold 166233 = 40mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and yellow gold) 116622 = 40mm; Rolesium (stainless steel and platinum) 116621 : 40mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and Everose gold) 116655 = 40mm; solid 18k Everose gold with Cerachrom bezel 268621 = 37mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and Everose gold) 268655 : 37mm; solid 18k Everose gold with Cerachrom bezel 268622 : 37mm; Rolesium (stainless steel and platinum) 68623 = 35mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and yellow gold) 68628 = 35mm; solid 18k yellow gold 168622 = 35mm; Rolesium (stainless steel and platinum) 168623 = 35mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and yellow gold) 168628 = 35mm; solid 18k yellow gold 169623 = 29mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and yellow gold) 169628 = 29mm; solid 18k yellow gold 169622 = 29mm; Rolesium (stainless steel and platinum) 69628 = 29mm; solid 18k yellow gold 69623 = 29mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and yellow gold)

Yacht-Master II

116680 = 44mm; stainless steel with Cerachrom bezel 116689 = 44mm; solid 18k white gold with platinum bezel 116688 = 44mm; solid 18k yellow gold with Cerachrom bezel 116681 = 44mm; Rolesor (two-tone steel and Everose gold) with Cerachrom bezel

Everything You Need To Know About The Rolex Yacht-Master Features & Options

Since the first all-gold Yacht-Master was released in 1992, Rolex has expanded the line with a variety of aesthetic details and mechanical upgrades. Here, we’ll explore the different options available on both the retail and secondary market for the Rolex Yacht-Master collection.

Rolex Yacht-Master materials

Today, Rolex no longer makes yellow gold versions of their standard Yacht-Master model, replacing it with Everose (their proprietary rose gold alloy) and 18k white gold. However, the 42mm version is the only white gold version (which was only just introduced at Baselworld 2019) is the only white gold model, as well as the only 42mm model in the collection. – Yellow Gold (discontinued) – Yellow Rolesor two-tone (discontinued) – Everose Gold – Everose Rolesor two-tone – White Gold – Rolesium (Oystersteel and platinum)

Rolex Yacht-Master sizes

Rolex has produced this luxury sports watch in a few different sizes to ensure that everyone has a Yacht-Master that fits their wrist perfectly. However, the smaller sized Yacht-Master models, known as the Lady Yacht-Master watches, have been discontinued in favor of the newer 37mm models. Today, women are reaching for more unisex sizes and designs, which could be what lead to the decision by Rolex. But that doesn’t mean women collectors are strapped for choice — as the current retail models are incredibly luxe and sophisticated for enthusiasts of both sexes. Furthermore, the secondary market is a great place to still get your hands on the smaller sized Midsize and Lady Yacht-Master models, and going pre-owned also opens up the doors to now-discontinued models like the solid yellow gold Yacht-Master watches. – 29mm (discontinued) – 35mm (discontinued) – 37mm – 40mm – 42mm

Rolex Yacht-Master bezel

With the Rolex Yacht-Master, the materials and aesthetics of the bezel depend on the material used for the case. With the Yacht-Master, there are bezels that consist of solid 950 platinum or 18k gold with raised, polished numerals. There are also bezels that are matte black Cerachrom ceramic with raised numerals, which are typically only fitted to the various solid 18k gold Yacht Master references. One of the less common and more flashy Yacht-Master bezels is nicknamed the “gummy bear” and it features rainbow-colored sapphires set around the bezel.

Rolex Yacht-Master dial

The dial of the Yacht-Master is quite archetypal of other Rolex sports watches. To ensure the watch is easily readable, the dial layout of the Yacht-Master features Mercedes-style hands, lume-filled hour markers, and a date window over at 3 o’clock. The dial itself is protected by a scratch-resistant sapphire crystal that has a Cyclops magnification lens for easier reading of the date. When it comes to the dial color of the Yacht-Master, there are several colors and materials that have been used over the years, like the beautiful blue dial on the ref. 116622 or the luxe sandblasted platinum dial that can be found on the now-discontinued version of this reference.

Rolex Yacht-Master bracelet

The Rolex Yacht-Master only ever features either an Oyster bracelet or an Oysterflex bracelet. The iconic, three-link bracelet Oyster bracelet is a Rolex staple, and it is featured across nearly the brand’s entire collection — from the Datejust to the Daytona to the Yacht-Master. In 2015, Rolex also introduced the now-famous Oysterflex bracelet on the then-new Everose gold Yacht-Master. This rubber bracelet is far more impressive than it appears at first glance. The rubber strap is actually reinforced by an internal flexible metal blade, making it incredibly durable and sporty, while still having this elevated aesthetic that matches the overall luxury feeling of this timepiece.

Rolex Yacht-Master movement

Depending on the size of the Yacht-Master watch, it will have a different movement to fit the case. Additionally, in 2019, Rolex updated the 40 version of the watch to feature the new-generation Cal. 3235 movement. Below are the sizes Rolex has used in its various Yacht-Master watches over the years.

– 29mm : Caliber 2135; Caliber 2235 – 35mm : Caliber 2135; Caliber 2235 – 37mm : Caliber 2236 – 40mm : Caliber 3135; Caliber 3235 – 42mm : Caliber 3235

Everything You Need To Know About The Rolex Yacht-Master II Features & Options

Below, we’ll outline the different options available on both the retail and pre-owned market for the Rolex Yacht-Master II collection.

Rolex Yacht-Master II materials

In keeping with the inherently luxurious feel of the Yacht-Master line, the Rolex Yacht-Master II is outfitted in some of the world’s finest alloys. Many collectors love this watch for its combination of precious metals and durable stainless steel — what Rolex calls Rolesor. On the Yacht-Master II, there is the Everose Rolesor which is beloved for the warm pink hue of its 18k Everose gold components. Another great combination is the white gold and platinum Yacht-Master II; however, this is obviously a much more opulent choice at represents the top-of-the-line offering in the Yacht-Master II lineup. Of course, there is also a stainless steel option with a blue ceramic bezel for those who just want sheer practicality and durability. Unlike the standard Yacht-Master, you can get this larger, more complicated timepiece outfitted in solid yellow 18k gold if you really want to go all out. – Yellow Gold – Everose Rolesor two-tone – White Gold and platinum – Oystersteel

Rolex Yacht-Master II sizes

There are a lot of features that separate the Rolex Yacht-Master II from the standard Yacht-Master, and the 44mm size is immediately one of the most noticeable. While the Yacht-Master II case is just 2mm larger than the largest Yacht-Master, this extra-large sizing helps this watch house a more complicated dial and movement.

– 44mm

Rolex Yacht-Master II bezel

Another one of the big differentiators with the Yacht-Master II is that large, beautiful bezel. The bidirectional rotatable ‘Ring Command bezel’ on the Yacht-Master II is specifically designed to help the wearer time out a regatta. Unlike most bezels that operate independently from the internal movement, the ‘Ring Command’ bezel on the Yacht-Master II actually works with the watch’s state-of-the-art movement. Rotating the bezel unlocks access to the programmable countdown timer, enabling quick and easy setting for use during competitions. While the design is incredibly complex, the aesthetics are beautifully simple.

When it comes to the look of the bezel itself, the Yacht-Master II does differ from the standard Yacht-Master. While a two-texture timing bezel defines the original model, the real star of the Rolex Yacht-Master II is that bright, beautiful blue Cerachrom bezel. This blue ceramic bezel is featured on the stainless steel, yellow gold and two-tone Everose Rolesor Yacht-Master II watches; however, the white gold models receive their bezels in sandblasted platinum.

Rolex Yacht-Master II dial

The Rolex Yacht-Master II dial layout is stunning, sophisticated, and totally different than any of the other Rolex dials due to its niche complication. On the dial, you will find a variety of features including the countdown display (which can be programmed anywhere from 1 to 10 minutes) that you can read via the red arrow-tipped hand. You will also notice the central flyback/fly-forward chronograph hand, the center hour and minute hands, and the running seconds sub-dial.

The dial of the Rolex Yacht-Master II is also outfitted with 12 lume-filled hour makers for added readability. Today, the most modern references are outfitted with Rolex’s Chromalight display, which is a luminescent material that emits a blue long-lasting glow.

You will also notice a big difference between the dial of the new generation of Yacht-Master II watches and the first generation, which featured baton-style hands that pointed to square hour markers. It was only in 2017 that Rolex decided to marry the style of the Yacht-Master II with the brand’s famous Mercedes-style hands. Rolex also updated the hour markers to feature a triangular hour marker at 12 and a rectangular hour marker at 6, rather than just square-shaped markers all the way around.

Rolex Yacht-Master II bracelet

Unlike the Yacht-Master which has two bracelets, the Rolex Yacht-Master II is only available with an Oyster bracelet. The sporty, durable 3-piece link bracelet is a staple for the brand’s sports watches, which makes it a perfect choice for this professional regatta watch. Rolex has also outfitted this Oyster bracelet with an Oysterlock folding clasp, built specifically to prevent the wearer from losing the watch due to accidental opening. This is a great feature for this model, which is purpose-built to be used during tough racing conditions.

Rolex Yacht-Master II movement

It’s clear that the Rolex Yacht-Master II is an incredible looking timepiece. But, the most impressive part of this watch is by far its movement. When the watch was first released, the Yacht-Master II was outfitted with the brand’s Caliber 4160, with Caliber 4161 making its debut a few years later in 2013.

The Rolex Yacht-Master II features one of the brand’s most complicated in-house movements to date — the self-winding mechanical chronograph, caliber 4160/4161. This movement boasts high-tech features like a countdown timer with both flyback and fly-forward functionality and a mechanical memory with on-the-fly chronograph synchronization, making it incredibly sophisticated. Additionally, the bezel (aka the Ring Command Bezel) is actually connected to the mechanism itself, allowing the wearer to adjust and set the countdown feature quickly and easily on the go. Rolex says it took its engineers some 35,000 hours of development to create this mechanism — and we think it was well worth it. – Ref. 116689 : Caliber 4160; Caliber 4161 – Ref. 116688 : Caliber 4160; Caliber 4161 – Ref. 116681 : Caliber 4160; Caliber 4161 – Ref. 116680 : Caliber 4161

Celebrities Who Wear the Rolex Yacht-Master

It probably doesn’t come as a surprise that one of Rolex’s most bold and luxurious watches is popular among the world’s most famous celebrities. One of the most well-known A-listers to sport the Yacht-Master is Mark Wahlberg, who is already a really big Rolex fan. We’ve seen him out and about in a solid 18k yellow gold Rolex Yacht-Master II, which totally pops against that blue ceramic bezel. Mark has no trouble making a statement with his watches, and that’s clear with this stunning timepiece.

Tennis champion Roger Federer also famously sports the top-of-the-line 18k white gold and platinum Yacht-Master II, while comedian and host Ellen DeGeneres is often spotted wearing her the 18k Everose gold Yacht-Master 40 with a black Cerachrom bezel and a black Oysterflex bracelet. Other celebrities that have been seen wearing the Yacht-Master include the following list of names, although there are many other stars who proudly have a Rolex Yacht-Master in their collections. – Russell Crowe – Lydia Ko – Sir Robin Knox-Johnston – Mark Wahlberg – Bruce Willis – Connor McGregor – Emeril Lagasse – David Beckham – Guy Fieri – Steven Gerrard – A$AP Rocky – Billy Joe Saunders – Flo Rida – Drake – Manny Pacquiao – Ellen DeGeneres – Ed Sheeran

How to Style The Rolex Yacht-Master

The Yacht-Master was an instant classic when it was introduced by Rolex, which means that it is incredibly easy to work it into your wardrobe. What we love so much about this watch collection — whether we’re talking about the Yacht-Master or the Yacht-Master II — is that it has this incredible balance of luxury and sports-oriented performance. Being able to dress this watch both up and down is what makes the Rolex Yacht-Master so much fun to wear. Here are just three classic ways you can wear this watch.

Yacht-Master with Bracelets

Ladies love this watch for its luxe finishing and superior durability. What woman doesn’t want a watch they can wear to drinks, diving, or lounging in the cabana? Because of that, we love pairing a beautiful two-tone Rolex Yacht-Master with bangles and bracelets that match the gold components on the watch. For example, we love the pairing of the 29mm Lady Yacht Master ref. 169623 with a gold Cartier love bracelet bangle and a linked chain. If you’re feeling really bold, you might as well go all out and pair your gold bracelets with a solid, 18k yellow gold Yacht-Master. Fair warning: you’re going to not be able to stop staring at your wrist. Chances are, no one else will be able to either.

Dressing Up With The Matte Black ref. 268655

We love this unisex 37mm timepiece because it works equally well on both men and women’s wrists. What makes this watch so special is the rubber Oysterflex strap watch that allows it to be sporty and durable. Matching that bracelet with the matte black bezel and dial really elevates the entire watch, which looks handsome and luxurious with the warm 18k Everose gold case. So when evening comes, head to the bar for sundowners wearing this ref. 268655. Of course, it will look good with a dark jacket. But, this watch will really pop if you pair it with a warm-colored shirt that accentuates the natural Everose hue. Finish the outfit off with dark wash jeans and you’ve mastered the elegant-meets-accessible look that defines this modern luxury watch.

Casual Elegance with the Yacht Master II

The two-tone Everose Rolesor Yacht-Master II is the ultimate luxury sports watch. You have luxury elements like the ceramic Cerachrom blue bezel and 18k Everose gold alongside durable Oystersteel and one of Rolex’s most complicated mechanisms to date. Because of this watch’s exclusivity, durability, water resistance, and functionality, there really isn’t a better choice for spending time on the high seas. And while this watch was built to time out a regatta, it is going to look just as good on your wrist while you lounge, swim, and play. We suggest pairing your Two-Tone Everose Rolesor’s blue bezel with a matching blue suit. Alternatively, you can pair it with a white and blue pinstripe shirt, rolling up the sleeves and unbuttoning the top few buttons to make your look feel more casual.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Rolex Yacht-Master

What is the difference between the yacht master and the yacht master ii.

The standard Rolex Yacht-Master is a luxury-oriented sport watch that displays the time and date. The Yacht-Master II joined the Rolex lineup in 2007 and offers never before seen functionality thanks to its regatta timer. Powered by the Calibre 4161 — one of the most complicated Rolex movements ever made (second only to the annual calendar found in the Sky-Dweller — the Yacht-Master II has a patented mechanical memory and on-the-fly-synchronization used for the regatta timer. Additionally, the bezel is different on the Yacht-Master II because it controls part of the movement inside the case rather than just working as an external mechanism to help track elapsed time. The Rolex Yacht-Master II also has an entirely different aesthetic and features a larger 44m case with chronograph pushers on either side of the winding crown.

Is a Rolex Yacht Master a good investment?

Yes. The Rolex Yacht-Master is a good investment for collectors for two main reasons. For one, these watches have historically held great value because of their uniqueness and sportiness; however, at the present time, they remain somewhat undervalued compared to their siblings in the Rolex catalog. Consequently, they offer significant potential for appreciation in the future. Secondly, the Rolex Yacht-Master is a luxury watch and is often outfitted in precious metals. These precious metals inherently allow it to hold great value as the years go on, and its premium construction guarantees that it will always be worth something.

What was the Rolex Yacht-Master built to do?

The Rolex Yacht-Master was first created as a luxury sports watch, whereas the Yacht-Master II was built as a professional regatta timer with a luxury flare. Comparatively, the Yacht-Master can time events up to 60 minutes with its rotating bezel and the Yacht-Master II is outfitted with a countdown timer with flyback or fly-forward functionality to use when timing out a regatta race.

How do you use the Yachtmaster II?

While the Yacht-Master II looks quite complicated, Rolex has made sure that using it is actually quite intuitive. After setting the adjustable countdown timer to your desired setting, you start the time. Press the top button to start the countdown timer, then pressing the top button a second time will stop the timer. However, by pressing the bottom button while the chronograph is running, that will adjust the timer forwards or backward to the nearest minute — allowing it to be perfectly synchronized to the official race clock.

How can I spot a fake Rolex Yacht Master?

As with any Rolex watch, the clues are in the details. When it comes to the Yacht-Master, you’re going to want to look at details like the adjustable countdown timer, which is incredibly complicated, making it almost impossible for fake counterfeit watches to replicate. Additionally, Yacht-Master models are luxury sports watches crafted from the world’s best materials and to the highest possible standards. If you notice any defects like dial printing or finishing looks less than perfect, there is a good chance that you are dealing with a fake Rolex Yacht-Master.

About Paul Altieri

Paul Altieri is a vintage and pre-owned Rolex specialist, entrepreneur, and the founder and CEO of BobsWatches.com. - the largest and most trusted name in luxury watches. He is widely considered a pioneer in the industry for bringing transparency and innovation to a once-considered stagnant industry. His experience spans over 35 years and he has been published in numerous publications including Forbes, The NY Times, WatchPro, and Fortune Magazine. Paul is committed to staying up-to-date with the latest research and developments in the watch industry and e-commerce, and regularly engages with other professionals in the industry. He is a member of the IWJG, the AWCI and a graduate of the GIA. Alongside running the premier retailer of pre-owned Rolex watches, Paul is a prominent Rolex watch collector himself amassing one of the largest private collections of rare timepieces. In an interview with the WSJ lifestyle/fashion editor Christina Binkley, Paul opened his vault to display his extensive collection of vintage Rolex Submariners and Daytonas. Paul Altieri is a trusted and recognized authority in the watch industry with a proven track record of expertise, professionalism, and commitment to excellence.

Bob's Watches Blog Updates

Sign up and be the first to read exclusive articles and the latest horological news.

Bob's Watches / Rolex Blog / Watch Buying Guides

Recommended Articles

Omega Seamaster Ultimate Buying Guide

Vintage Watch Reviews Under $30k: The Rolex Explorer Reference 1016

13 Best Summer Watches

You may also like.

Rolex GMT-Master

Rolex GMT-Master II Ref 126710 Batman Oyster

Rolex GMT-Master II Ref 126710 Jubilee Bracelet

Rolex GMT-Master II Ref 126710 Batman

A buying guide to most popular Rolex Yacht-Master Models

Guide To Popular Rolex Yacht-Master Models

Rolex debuted the Yacht-Master watch in 1992 as a luxury sports watch crafted in precious gold yet durable enough for an active life at sea. The nautical-inspired Rolex watch featured a rotating timing bezel, a water-resistance rating of 100 meters, and a time and date dial. The Yacht-Master shared many design traits with the famed Submariner watch—such as a similar dial layout, case silhouette, and bracelet style—but it was a touch more luxurious thanks to its own set of design details. Over the course of its history, the Rolex Yacht-Master collection has expanded into a varied lineup with watches offered in several sizes, materials, and colors. Here’s a guide to some of the most popular Rolex Yacht-Master watches, ranging from discontinued models to current-production ones.

Where it all began:

The very first Yacht-Master model that Rolex released was a full yellow gold version. It sported a 40mm yellow gold case, a yellow gold rotating bezel with raised numerals, and a yellow gold three-link Oyster bracelet. Two years later in 1994, Rolex followed it up with two other yellow gold models—a ladies’ 29mm version and a midsize 35mm version. While Rolex no longer produces full yellow gold Yacht-Master models, they remain popular in the secondary market.

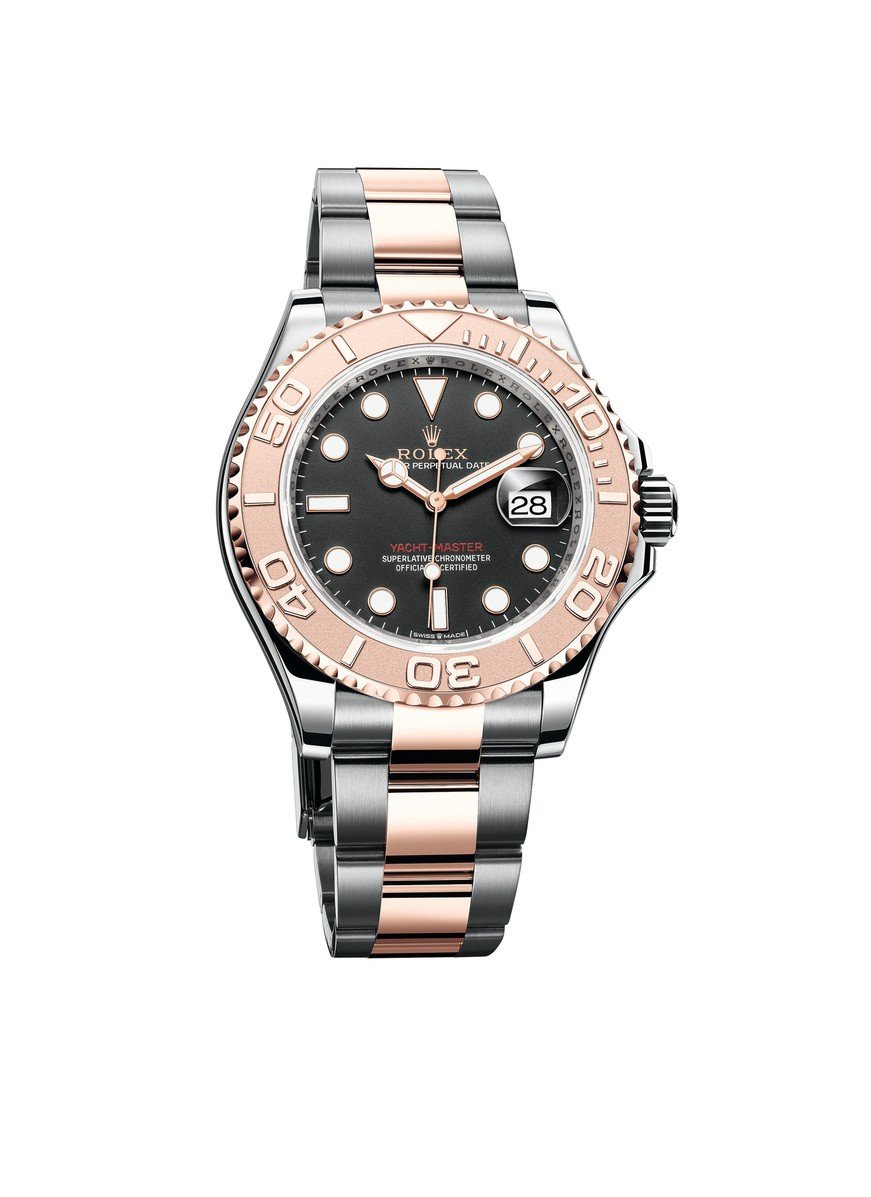

In 2015, Rolex introduced the very first Everose gold (the brand’s own rose gold pink alloy) Yacht-Master. However, rather than a full gold model, the Everose gold Yacht-Master models (available in 40mm and 37mm) included black ceramic bezels with raised numerals and a brand new black rubber-clad metal band called the Oysterflex bracelet. Dial options include sleek black and lavish diamond-paved. It’s also worth mentioning that there are some rare Everose gold Yacht-Master 40 models furnished with rotating bezels set with multi-colored precious gems (diamond, sapphire, and tsavorite).

Here is a flamboyant version of it of the Everose gold Yacht-Master 40:

Finally, in 2019, Rolex released the first white gold Yacht-Master watch. Not only is this the only white gold Yacht-Master model ever made, but with its 42mm case, it is also the largest.

Similar to the Everose gold model, the white gold Yacht-Master is fitted with a black ceramic bezel and black Oysterflex bracelet, along with a black dial.

Prices (current collection):

- Everose Gold Yacht-Master 37 ref. 268655: $23,250 - 41,000

- Everose Gold Yacht-Master 40 ref. 126655: $27,300 – 47,150

- White Gold Yacht-Master 40 ref. 226659: $28,900

Rolesium Rolex Yacht-Master Models

In 1999, Rolex presented a new metal combination the brand called Rolesium, which brings together stainless steel and platinum on one watch. Like the yellow gold models, the Rolesium Yacht-Master models were offered in 40mm, 35mm, and 29mm versions.

Regardless of the size, all the watches include stainless steel cases, stainless steel Oyster bracelets, and platinum rotating bezels with raised numerals. Particular popular versions of the Rolesium Yacht-Master watches are those with sandblasted platinum dials—although discontinued, these platinum dial Yacht-Masters are still widely available in the pre-owned market.

Currently, Rolex still makes steel and platinum Yacht-Master watches. However, size options have been scaled down to 40mm and 37mm since Rolex stopped making 29mm or 35mm versions of the Yacht-Master around 2015. The Rolesium Yacht-Master 40 offers the choice between a rhodium gray or a blue dial while the Rolesium Yacht-Master 37 only comes with a rhodium gray dial.

Prices (current collection):

- Rolesium Yacht-Master 37 ref. 268622: $11,250

- Rolesium Yacht-Master 40 ref. 126622: $12,000

Rolesor Rolex Yacht-Master Models

Rolesor is the term Rolex gives to its models that mix gold and steel details—better known as two-tone watches. The first two-tone Yacht-Master watches, which featured steel cases topped with yellow gold bezels and steel Oyster bracelets with yellow gold center links, were launched in the mid-1990s. However, Rolesor Yacht-Master watches were first only offered in midsize (35mm) and ladies (29mm) sizes. The men’s 40mm two-tone yellow gold and stainless steel Yacht-Master joined the lineup in the early 2000s. Rolex stopped making yellow gold and steel Yacht-Master models a few years back but the brand has replaced them with another Rolesor option—two-tone Everose gold and steel ones. The current-production two-tone Yacht-Master models include stainless steel cases topped with Everose gold bezels and stainless steel Oyster bracelets with Everose gold center links. The Everose Rolesor models are available with 40mm or 37mm cases and both sizes offer the option between a black or brown dial.

- Everose Rolesor Yacht-Master 37 ref. 268621: $13,150

- Everose Rolesor Yacht-Master 40 ref. 126621: $14,500

In less than three decades, the Yacht-Master has grown to become Rolex’s most diverse sports watch collection, offering a vast assortment of sizes and styles for both men and women. From the discontinued models to the current-production ones, the Yacht-Master’s distinct combination of luxury and robustness has paved the way for its enduring popularity.

Find out more:

To find out more about which Rolex hold their value you can read more of our guides where we cover all Rolex Nicknames or our classic guide to the Day Date models and our comparision with their sister brand: Rolex vs Tudor .

Subscribe our newsletter for more news related content and find our quick comparitive guides to help you decide which watch you should buy next:

Breitling vs Rolex

Cartier vs Rolex

Audemars Piguet vs Rolex

Tag Hurer vs Rolex

- Latest Releases

The fastest and most secure way to protect the watches you love.

We've minimized the paperwork and maximized protection, so you can stop worrying about your watches and focus on enjoying them.

In most cases, you'll get a personalized quote in seconds and your policy kicks in immediately.

Wherever you are on planet Earth, your watches are protected. Rest easy and travel safely.

If you suffer a covered loss, there's no deductible and no gimmicks. Ever.

Each of your watches is covered up to 150% of the insured value (up to the total value of the policy).

Our quotes are based on historical sales and real-time market data allowing us to give fair prices without all the hassle.

Popular Searches

Introducing A New Limited Edition Bulgari Octo Finissimo Sketch Gives You A View Of The Back, From The Front

Shop Spotlight Exploring Longines’ Multifaceted Approach To Watchmaking (And Design)

Hands-On The New Bulova Lunar Pilot Meteorite Edition Reminds Me Just How Important This Watch Is

A Week On The Wrist The Rolex Yachtmaster 40mm With Oysterflex Bracelet

For the first time, rolex is delivering a watch on a rubber strap – except in classic rolex fashion it's not a rubber strap at all. it's a beautifully over-engineered bracelet called the oysterflex..

Editors’ Picks

How To Wear It The Cartier Tank Cintrée

In-Depth Examining Value And Price Over Time With The ‘No Date’ Rolex Submariner

Watches In The Wild The Road Through America, Episode 1: A Model Of Mass Production

There is big news, and there is Rolex big news, and in some ways, ne'er the twain shall meet. At Baselworld this year, Rolex debuted a first for the company: the very first, ever, Rolex delivered on a rubber strap. Now, for most companies this would have little effect on watch enthusiasts other than to evoke (very) tepid interest at best, and boredom at worst – but this is not an ordinary rubber strap, this is an official, designed-and-tested-and-thoroughly-obsessed-over-by-Rolex rubber strap. And thereby hangs a tale.

The Yachtmaster, as we have mentioned in some of our previous coverage , occupies a somewhat particular place in Rolex’s lineup of sports watches; it shares water-resistance and a turning bezel with the Submariner (the latter is water resistant to 300 m while the Yachtmaster standard model is water resistant to 100 m). It is certainly not a tool watch; the Yachtmaster is offered in either platinum and steel, or gold and steel (that’s Rolesium and Rolesor, lest we forget) and is either quietly or unequivocally luxurious depending on what size and metal you go for (Rolex makes the Yachtmaster in both 35 mm and 40 mm sizes).

The Yachtmaster’s history goes back to the first introduction of the watch in 1992, although the name, interestingly enough, appears on the dial of a prototype Yachtmaster Chronograph from the late 1960s (a watch so legendary I am actually forced to use the word; one of three known is in the collection of Mr. John Goldberger; we covered it – and a host of other remarkable ultra-rare watches from his collection – in a very memorable episode of Talking Watches ).

The term “Yachtmaster” is also, incidentally, used for a certificate of competency in yachting which is issued by the Royal Yachting Association, although we’re unaware of any specific association between the RYA and the Yachtmaster watch.

Now, this newest version of the Yachtmaster does take a few pages from the existing Yachtmaster playbook: 100-meter water resistance, a bidirectional turning bezel, and a dial and hands that echo the Submariner. There are also a couple of features that may make vintage Sub enthusiasts wonder if Rolex mightn’t have an exceedingly subtle sense of humor; the gilt coronet and “Rolex,” and the red lettering, both features which according to HODINKEE founder Ben Clymer would have, had they appeared on a Rolex dive watch, made it instantly the single most popular watch in the modern Rolex inventory. The case is rose gold – Rolex famously makes their own, called Everose, in their own foundry, with a bit of platinum mixed in to prevent discoloration – and the bezel, rather than being some other precious metal (as is the case in the “standard” Yachtmasters) is in black Cerachrom – a very technical-looking matte black that contrasts sharply with the gold case. Somehow, between the rose gold, the Cerachrom bezel, and the new Oysterflex bracelet this manages to be the most luxurious and at the same time most technical Yachtmaster yet (leaving aside the Yachtmaster II, which we recently reviewed right here , but that is a watch that marches to the beat of a different drummer entirely).

The two different versions of the Everose Yachtmaster (40 mm and 37 mm) sport different movements; the larger uses the caliber 3135 and the smaller, the newer 2236, which sports the “Syloxi” silicon balance spring (first used by Rolex in 2014).

The Oysterflex bracelet is, in a nutshell, quite a piece of work. One of the most endearing traits of Rolex as a company is that it tends to demonstrate what we can only describe as a laudable degree of corporate obsessive-compulsive disorder when it comes to research and development, and it does so, often, without making any sort of fanfare about it at all. In this case we do know a little bit about the Oysterflex, however – it is basically designed to have the hypoallergenic and comfort properties of a rubber strap and the durability and shape-retention properties of a bracelet.

At the core of the Oysterflex bracelet are metal inserts made of titanium and nickel, which are used to affix the bracelet to the clasp and watch case; over those is a sheathing of “high-performance black elastomer.” “Elastomer” is a portmanteau word, formed from “elastic” and “polymer” and is a general term for natural and synthetic rubbers. In addition to the materials complexity of the Oysterflex bracelet, it is also shaped in a rather unusual fashion – there are ridges molded into the the wristward face of the bracelet, which are intended to allow the bracelet when worn to better approximate the natural curvature of the wrist.

They might look a bit odd but in practice, the design works out quite wonderfully; this is easily the most downright comfortable and organic-feeling rubber strap I have ever worn, and like the entire watch manages to be both extremely technical in feel, and very luxurious at the same time; I doubt whether any company has ever taken so much trouble over the design of a strap (for all that Rolex prefers the term “bracelet” in describing the Oysterflex, habit dies hard and you’ll probably find yourself calling it a strap, just as we did). On the wrist, the two stabilizing ridges do exactly what they are supposed to: keep the watch from shifting, as heavier watches on rubber straps are wont to do, without requiring you to have the strap uncomfortably tight. The Everose Oysterlock clasp does a superb job mechanically and also looks fabulous into the bargain; the quality of finish on the clasp and case may not seem terribly elaborate at first, but it is as technically flawless as anything I have ever seen at any price, on any watch.

What we have here, in other words, is a very Rolex interpretation of luxury. Yes, this is a gold watch, and a gold Rolex, and wearing a gold Rolex always carries with it, shall we say, certain semiotic complexities. However there is also another side to the watch, and to the Rolex approach to luxury in general: the taking of such pains to produce technical perfection that technical perfection becomes a luxury in itself.

The Everose Rolex Yachtmaster, in Rolex Everose, with Everose Oysterclasp and Oysterflex bracelet, as shown, $22,000 in 37 mm, and $24,950 in 40 mm. For more info, check out Rolex.com.

Watching Movies Tom Selleck's Tiny Timex And Two-Tone Rolex In 'Three Men And A Baby'

By Danny milton

Seven Of Our Favorite Watches To Engrave

By James stacey

Sunday Rewind Take A Deep Dive With The Rolex Sea-Dweller 126600

By Hodinkee

Pre-Owned Picks A Patek Philippe Nautilus Ref. 5711/1A, An Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore Chronograph, And An IWC Portugieser Chronograph Rattrapante

By Hodinkee shop

Last Week’s Top Stories

Introducing It's Finally Here: Omega Announces A White Dial Speedmaster In Steel – Oh, And It's A Lacquer Dial

By Mark kauzlarich

Introducing The Next Generation Of Seiko's Prospex '20MAS' – Now Smaller And With A New Movement (SPB453, SPB451 & SPB455)

Hands-On The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar John Mayer Limited Edition (Live Pics)

Watch Spotting At The 96th Annual Academy Awards

By Malaika crawford

Introducing Seiko Debuts The New Presage Classic Series With Softly Textured Dials

By Anthony traina

The Rolex Yachtmaster: history, models, price

Table of Contents

(NEWS) The Monaco Legend Group will auction a one-of-a-kind Rolex Yacht-Master

The rolex yacht-master dix millionieme chronometre.

The Yacht-Master auctioned on April 22 and 23 in Monaco is one of the most attractive one-of-a-kind contemporary Rolex watches and popped up in the early nineties to celebrate the ten-millionth Rolex watch equipped featuring the Chronometer Certificate.

Interestingly, it is not a Daytona, a Submariner or a Day-Date but a Rolex Yacht-Master, thus adding additional flavour to our guide as no other model could ever do. May we call it the Rolex Yacht-Master Heiniger ? Yes, we might, but we need to move forward and provide further details.

The Heiniger family and Rolex

The model pictured here was manufactured under the Heiniger family’s leadership at Rolex; they managed the brand since Andre Heiniger was appointed President of Rolex in 1964 through his son Patrick’s appointment in 1992.

This one-off platinum Yacht-Master is a prototype conceived to celebrate such a milestone and holds all the features found on first-class super-exclusive Rolex timepieces, and adopts baguette-cut sapphires and diamonds replacing the stock indexes plus the “DIX MILLIONIEME CHRONOMETRE” print on the dial, and the calibre 3135’s oscillating mass.

The Heiniger family had, no doubt, a soft spot for platinum watches ; three unique platinum Daytona also appeared under their management and, according to industry’s rumours, the Daytona 116598 SACO, better known as the Leopard, was among their projects inspired, it seems, by Nina Stevens, Patrick Heiniger’s girlfriend back then.

However, the Rolex Yacht-Master Heiniger is not a unicorn adorning a watch museum ; it will soon go under the hammer thanks to the Monaco Legends Group, the auction house co-managed by vintage watchmaking guru Davide Parmegiani, the 22 and 23 April.

Given the relevance of the timepiece and its exclusivity, we expect fierce competition among collectors to make this piece theirs. What is the auction’s base price? The current estimation is between one and two million euros , quite a hefty price gap but something hard to predict for any watch expert.

The origins of the Rolex Yachtmaster

When did the Rolex Yachtmaster first appear? It’s hard to define. The name “Yacht Master” was filed for patent by Rolex in 1950 and, according to rumours and several non-confirmed historical sources, marked the brand’s willingness to introduce a new collection atop the top-selling and sporty Submariner; yet, it’s hard to describe the time lapse between patent and the first official commercial release. When we look at the current collection, we can also find inspiration in the most challenging endeavours across the oceans, up to professional yacht racing.

For instance, the former includes the expeditions set out by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston . He completed the first-ever solo circumnavigation of the globe, the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race of 1969, but we can’t forget what Sir Francis Chichester achieved, too; he circumnavigated the world from West to East in nine months and one day between 1966 and 1977 aboard the never-forgotten Gipsy Moth IV.

During his expedition, Chichester wore a Rolex Oyster Perpetual Chronometer, laying the foundations for what a Rolex watch represents when tested under extreme weather conditions on land, sea and air.

The first Yachtmaster

The first Rolex Yachtmaster dates back to 1992 ; it was marketed as reference 16628 and is the second most recent new Rolex watch after the more contemporary Rolex Sky-Dweller.

The collection’s timeline has undergone a bizarre evolution compared to similar Rolex watch collections.

Showcasing an 18-carat yellow gold case and bracelet paired with an unusual white dial , it housed the movement 3135 and is undeniably an evolution of the design codes seen on a Submariner, despite the journey to the first edition being unexpected and with plenty of testing prototypes.

Was the Yachtmaster pictured above the first attempt ever? It was from a commercial standpoint, not from a product perspective instead. The Yachtmaster moniker first surfaced between 1967 and 1969 when Rolex released a couple of prototypes based on the Daytona , whose case diameter had grown to 39.5 mm. The timepieces mentioned above belong to Italian collector John Goldberger and artist Eric Clapton.

The Rolex Yacht-Master 40 and 37 mm

Here is the Yacht Master’s “bread and butter”, undergoing several evolutions to end up with the model pictured here, as an example, in its gold and steel livery. With Jean-Frèdèric Dufour appointed CEO, Rolex has revisited the entire offering, which includes 40 and 37-mm large models, but has never hit the spot as the most wanted Professional Rolex among enthusiasts. The Daytona , Submariner, or GMT Master 2 are far more sought-after than any Yachtmaster, although the appreciation has steadily grown year after year .

Instead, the Yachtmaster’s technical development began with the 2007 Rolex Yacht-Master 2 116680 , whose sailing-professionals-oriented complication proves, alongside a Rolex Sky-Dweller, how much Rolex technicians are up to the task when asked to design a mechanically complicated watch.

Rolesor and Rolesium.

The current Yachtmaster collection with bracelets includes a completely revised range, comprising seven models : four 40 mm and three 37 mm models. They are available exclusively in steel and gold or platinum; some come in Rolesium (steel and platinum), others in Rolesor (steel and gold) such as, for instance, the Rolex Yachtmaster 40mm model in steel and Everose gold pictured here, also available with a black dial and as a 37mm size.

Let’s look closer at the Rolex Yacht-Master 40 in Steel and Everose Gold : it combines 904L steel and Everose pink gold, the Rolex-patented pink gold alloy adopting a specific silver and copper percentage to create an alloy capable of offering above-the-average shine, and wear resistance over time.

The Yachtmaster’s bezel

What makes the Yacht-Master unique is the bezel’s design in finish and functionality; it houses mirror-polished raised indexes and numerals on a sandblasted base and comes as a one-piece of gold or platinum. The polished to brushed finish appears on the Oyster bracelet and case sides, lugs included.

The Yachtmaster is widely considered a more luxurious take on the Submariner and a transition model between a sporty and classic Rolex watch with a gold case, as proved by the slightly curved lugs and the case side, making the Yachtmaster closer to four and five-digit Submariners as less professional than other timepieces belonging to the same product category, as exemplified by the specs sheet. The bezel is graduated but is bidirectional and water-resistant up to 100 metres .

Comparing current and first-ever Yachtmaster like the Rolex 69623 or 169622, for instance, lies in the options available: you’ll find the blue dial exclusively available on Rolesium models, while the Rolesor offers a chocolate brown or black dial , lovingly contrasting the case and bracelet’s tones, in our opinion.

The calibre 3235

Since 2019, the Rolex Yachtmaster has housed the latest-gen Rolex calibre 3235. Therefore, all models can run for at least 70 hours when fully wound.

The watch is certified as a Superlative Chronometer according to Rolex standards.

The calibre 2236

Instead, the 37 mm model adopts the smaller movement 2236, whose technical specifications differ slightly .

The main difference is that the Siloxy hairspring with a flat terminal curve , introduced by Rolex in 2014, replaced the Parachrom Blue one.

The Rolex Yachtmaster Oysterflex

At Baselworld 2015, Rolex released the first Yachtmaster with an Oysterflex bracelet , the brand’s patented rubber strap equipped with an inner nickel and titanium alloy, exclusively offered with a 40mm or 37mm gold case. Looking back at the first-ever YM, the Yachtmaster Oysterflex is perhaps the perfect successor to the 1992 Yacht Master.

The first release appeared in Everose rose gold. Such a new generation best embodies the collection’s spirit ; it belongs to the Professional line of watches but is more luxurious, and gold highlights the Yacht Master’s “carrure”.

The new Yachtmaster Oysterflex also introduced the first-ever matte ceramic bezel ; it mimics a Rolesor or Rolesium’s, but the inlay is a single piece of matt black ceramic.

As with the two-tone models, the 40 and 37-mm case options adopt the 3235 and 2236 , respectively. The new model had a stunning success, and Rolex soon expanded the product range by offering a more generous 42 mm case size (however, the 40 mm model is unparalleled, in our opinion).

The 42mm collection is available in yellow or white gold , while the 40mm and 37mm models only come with an Everose rose gold case. We think Rolex will soon extend the Oysterflex collection by adopting new case materials.

In 2020, Ineos Britannia’s skipper Ben Ainslie was spotted wearing a titanium Yachtmaster 42 during a training session. After the Rolex Deepsea Challenge Titanium RLX ‘s unveil, this proto will likely make it to reality anytime soon.

Before moving to the next chapter, remember that we discovered an odd model while surfing the Rolex official website: Rolex Yachtmaster 42 Hawkeye or Yachtmaster Falcon’s Eye , pictured above.

The Rolex Yachtmaster 2

Rolex is a manufacturer whose capabilities include rather mechanically-complicated watches ; it is something most people are unaware of. In the same price range as a Daytona, for example, you can opt for at least two complicated models: one is the regatta-ready Yachtmaster 2.

If an ordinary Yachtmaster is not as “professional” as its siblings, the Yachtmaster 2 is a full-fledged tool watch for professional skippers.

The complicated Rolex: from the Sky-Dweller to the Yacht-Master 2

The Rolex Yachtmaster 2 is bold and hefty; it’s a regatta timer and something you will, on paper, disregard when compared to a Rolex Sky-Dweller. The Rolex Yachtmaster 2 was conceived to provide professional skippers with a wrist instrument capable of accurately measuring the countdown to start a regatta.

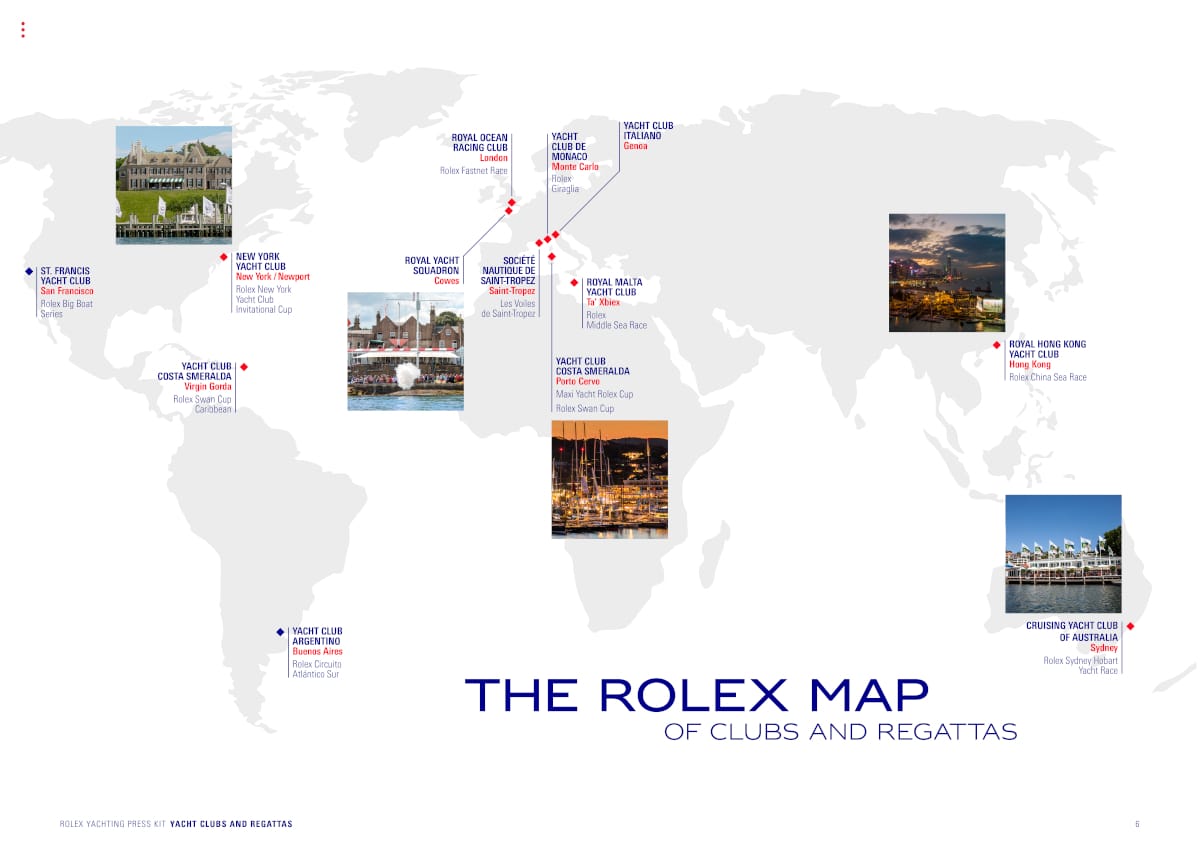

The link between Rolex and yachting is long-established: the brand has associated its image with several sailing competitions like the Farr 40 or the Sidney–Hobart ever since. Pictured below is a map of the current partnerships.

The 5 to 10 minutes preceding the start of a regatta are paramount to any skipper and their crew; last-minute performance before the start is triggered can separate victory from defeat.

Most Regatta watches do not offer a dedicated function but make the most of ordinary chronograph functions. In contrast, the Rolex Yachtmaster II has a dedicated counter on the dial, coaxial to the bezel, equipped with a graduated scale from 0 to 10 minutes and an easy-to-read arrow hand.

The Countdown function: how to activate it.

The timer setting is straightforward and achieved by combining the bezel, crown and button at 4 o’clock in this sequence. The first operation is to rotate the bezel counter-clockwise to activate the small countdown counter adjustment system.

The bezel will automatically lock after a 90° rotation or when the “Yacht-Master II” writing appears on the right-hand side of the watch (the rotation axis of the crown ideally cuts the wording in two halves). Subsequently, please push the button located at 4 o’clock. Unscrew the crown until it locks in position 1 ; from that moment on, you can control the adjustment of the (jumping) 10-minute scale in one-minute intervals by rotating the crown clockwise.

After stopping the minute counter on the desired value, you need to rotate the bezel clockwise until it clicks into the position where the “Yacht-Master II” writing is again aligned at the bottom (-90 °, back to the original place).

At the end of this rotation, the two-minute scales, located on the bezel and the dial, respectively, will be fully aligned. By screwing back in the winding crown, you can restart the countdown (using the button at 2 o’clock); the red hand in the middle will start running, and the minutes’ countdown will begin .

During the countdown, you can stop the hand can by using the button at 2 o’clock or re-set the complete countdown with the button at 4 o’clock (Flyback). The countdown will start from the original position in the second case scenario. When the countdown has finished, the minute’s hand will also stop, while the second’s hand will continue to run indefinitely. The Rolex Yachtmaster II is a chronograph with a Flyback function .

The 2017 Rolex Yachtmaster II 116680 reference has replaced the previous reference by introducing a series of updates ; the new version is now equipped with Mercedes-styled hands, thus aligning itself with the family feeling of the other Oyster Perpetual divers, like the Submariner. Moreover, new applied indices located at 12 and 6′ clock have been launched (arrow-shaped and rectangular-shaped, respectively).

Ring Command and calibre 4161

The Ring Command bezel is integrated with the calibre and is an active part of the user experience. The level of complication and perfection this mechanism requires (firm clicks and no play) is more challenging than any other Rolex timepiece, making this watch extremely attractive.

At the same time, as per the usual Rolex tradition, the complication is concealed through a simplified aesthetic , although the dial is still more complex and crowded than those standards that Rolex has made us accustomed to, and this is one of the reasons why a Rolex Yachtmaster II is rarely a first choice when it comes to selecting a timepiece.

Rolex Yachtmaster Prices

The price list starts with the Yacht-Master 37 mm at 14,450 Euros and grows to the 43,800 Euros needed for a Yacht-Master 2 model in yellow gold . For instance, a more exclusive price list is requested, as with the reference 126655. The listed price range here is updated to February 2023; if you’re looking for a more comprehensive overview, please head to our dedicated article; there, you’ll find a price list and evolution since 2021 regarding the most coveted professional Rolex watches.

(Photo credit: Horbiter®)

Editorial team @Horbiter®

Giovanni Di Biase

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Newsletter of Horbiter

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the latest news about the world of horology straight into your email box..

Your data is safe with us. Read more here: Privacy Policy

The Watch Of The Open Seas: History Of The Rolex Yacht-Master

Instagram: @rolex

In the year 1992, Swiss watchmaker Rolex would debut a new model line at the Baselworld show that was strikingly similar to the already-popular Submariner. It featured the same 40mm Oyster case with a rotating bezel, the same chronometer-certified caliber, and the same Oyster bracelet.

Seemingly the only difference between the two was the white dial of that first Yacht-Master, a style which has never been an option on a Sub, and the inferior depth rating of 100m when compared to the Sub’s 300m.

Yet, the Yacht-Master was well-received upon launch, and with the passing of time, the yachting-inspired model has evolved and pioneered its own path within Rolex’s catalog.

Read on with us as we go back to the beginning and track the catalysts that paved the way for the most recent Yacht-Master release, the Yacht-Master 42 (226659), to become one of the hottest sports timepieces of the year.

History Of The Rolex Yacht-Master

We’ve broken down our overview of the Yacht-Master into the following segments:

- Release Of The Yacht-Master

The Submariner/Yacht-Master Theory

- Mid-Size & Ladies’ Yacht-Master

- Platinum (Rolesium) Yacht-Master

The Maxi Dial Yacht-Master

- Two-Tone Rolesor Yacht-Master

The Yacht-Master II

- Six-Digit Yacht-Master

The Oysterflex Yacht-Master

Keep scrolling to read this guide from its beginning, or use the links above to jump down to a specific point.

Browse Bob’s Watches Rolex Catalogue

The Release Of The Yacht-Master

The first Yacht-Master watch was launched in 1992 under reference number 16628. It featured a yellow gold case, a bidirectional graduated bezel, and a matching full-gold Oyster bracelet. Its dial was white with black hour indices, while at center were gold Mercedes hands, and beating inside was the 3135 movement.

Rolex ref. 16628. Instagram: @m_j_watches

Previous to the Yacht-Master’s introduction, Rolex had not released a new model line in a quarter century. So, why did they go with the Yacht-Master, a design that risked being a detractor from their existing Submariner? Let’s take a look at the inspiration.

The sport of yachting is one which demands precise timing and extreme coordination of the entire crew for optimal performance, particularly in offshore competitions.

Prototype Daytona Yacht-Master ref. 6239. Image: Christies.com

Rolex believed their waterproof and chronometer-grade timepieces to be more than qualified to handle the knocks of a regatta and keep ticking accurately. The brand is also notorious for their marketing prowess, which led them to act quickly in establishing an association with the sport.

Beginning in 1958 with their first sponsorship of a race, the relationship has endured until today, when the brand sponsors over a dozen international yachting events.

Nevertheless, it’s hard to deny that there exists a large gap between first contact in 1958 and the release of the yacht-inspired timepiece in the early ’90s. Why wasn’t the Yacht-Master released earlier on?