Try now - Live tracking map for yachts and other vessels

Real time world map for tracking yachts and all other vessels like speed boats, cargo or tankers! Tracking yachts and other vessels was never so easy!

Rising Sun yacht: The luxurious world of Larry Ellison and David Geffen’s nautical retreat

Rising Sun is a notable super yacht known for its size and high-profile owners. Here are some key details about the Rising Sun yacht.

Brief Overview

Rising Sun was originally built for American business magnate Larry Ellison , the co-founder of Oracle Corporation. However, Ellison later sold a significant portion of the yacht to music and film producer David Geffen. Today it is co-owned by Larry Ellison and David Geffen.

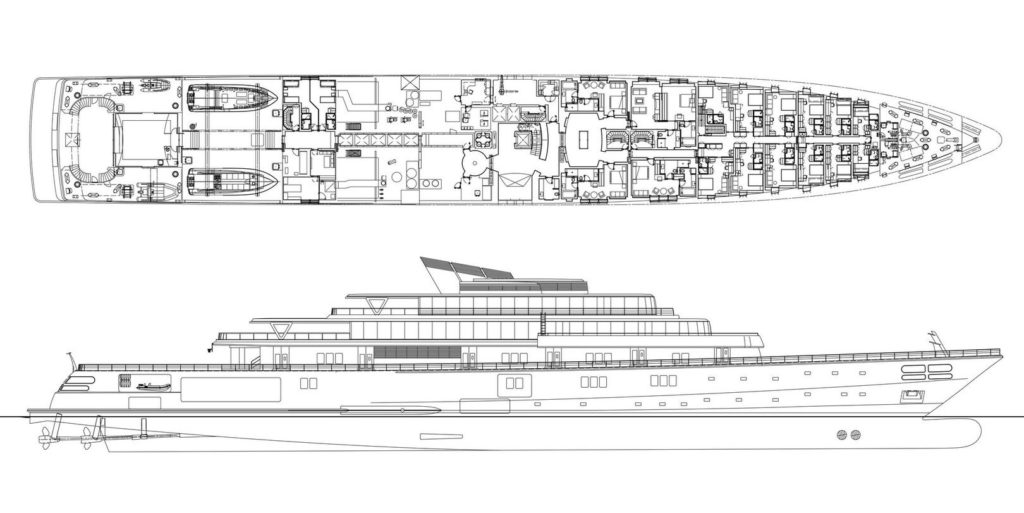

Rising Sun is approximately 454 feet (138 meters) in length, making it one of the largest yachts in the world at the time. Its impressive size allows for a wide range of amenities and luxuries.

Design and Features

The yacht boasts a stunning exterior design and a luxurious interior. It’s equipped with multiple decks, a swimming pool, a basketball court that can be converted into a helipad, and a variety of dining and entertainment spaces. The interior features opulent staterooms and lounges.

Cruising Range

Rising Sun is powered by powerful engines, which give it a a top speed of around 28 knots (about 32 mph or 52 km/h). This allows the yacht to cover vast distances on the open sea.

Part 1: Ownership of Rising Sun

Who are the notable owners of the rising sun yacht.

The Rising Sun yacht is co-owned by two prominent figures in the world of business and entertainment: Larry Ellison and David Geffen.

Who is Larry Ellison?

Larry Ellison is a renowned American entrepreneur and the co-founder of Oracle Corporation, one of the world’s leading software and cloud computing companies. With his immense success in the tech industry, Ellison has amassed substantial wealth and has used some of it to indulge in a life of luxury, including the ownership of Rising Sun.

Who is David Geffen?

David Geffen is a prominent figure in the entertainment industry. He is a music and film producer, co-founder of Asylum Records, and a co-founder of DreamWorks SKG. Geffen is known for his influence in the world of entertainment and, like Ellison, enjoys the opulent lifestyle provided by the Rising Sun yacht.

Part 2: Size, Design, and Features

How large is the rising sun yacht.

Rising Sun is a colossal super yacht, measuring approximately 454 feet (138 meters) in length. Its vast dimensions are a testament to its opulence and the array of amenities it offers.

What are the design and features of Rising Sun?

Rising Sun is an architectural marvel, featuring a stunning exterior design and an interior that exudes luxury. Onboard, guests can enjoy multiple decks, a lavish swimming pool, a basketball court that converts into a helipad, and a variety of dining and entertainment spaces. The interior is adorned with opulent staterooms and lounges, making it a floating palace on the seas.

Part 3: Cruising Range of Rising Sun

What is the cruising range of the rising sun yacht.

Thanks to its powerful engines, Rising Sun has an impressive cruising speed of approximately 28 knots, which translates to about 32 miles per hour (52 kilometers per hour). This remarkable speed allows the yacht to cover vast distances during its journeys across the ocean, providing its passengers with access to a wide range of destinations.

Part 4: Notable Guests of Rising Sun

Who are some of the notable guests who have been aboard rising sun.

Rising Sun has been a favored choice for hosting celebrities and high-profile events. Some of the notable guests who have had the privilege of experiencing the yacht’s luxury include:

- Oprah Winfrey : The iconic talk show host and media mogul has been spotted aboard Rising Sun, enjoying the yacht’s lavish amenities.

- Steven Spielberg : The renowned filmmaker and director has also graced the decks of Rising Sun, adding a touch of Hollywood glamour to its guest list.

- Tom Hanks : The beloved actor Tom Hanks has enjoyed the yacht’s hospitality during his time on the open seas.

- Bruce Springsteen : The rock legend Bruce Springsteen is another famous personality who has been a guest aboard Rising Sun, making his voyages truly unforgettable.

What makes Rising Sun a preferred choice for such guests?

Rising Sun’s opulent interior, world-class amenities, and exceptional service make it a sought-after destination for celebrities and high-profile individuals. Its spacious decks and luxurious accommodations provide the perfect backdrop for relaxation and entertainment, ensuring that every voyage is a memorable experience for its guests.

In conclusion, the Rising Sun yacht, co-owned by Larry Ellison and David Geffen, represents the epitome of luxury on the high seas. With its impressive size, breathtaking design, remarkable cruising range, and a list of notable guests that includes some of the biggest names in entertainment and business, it continues to be a symbol of opulence and indulgence in the world of super yachts. Whether you’re interested in its ownership, design, or the celebrities who have graced its decks, the Rising Sun yacht is a true icon of maritime luxury.

Technical specifications and additional details about the Rising Sun yacht

Length: Approximately 454 feet (138 meters)

Rising Sun has a steel hull and aluminum superstructure with a beam of 18.5m (60.70ft) and a 5m (16.40ft) draft.

Estimated to be around 7,500 tons

Cruising Speed: Approximately 28 knots (32 mph or 52 km/h)

Maximum Speed: Around 30 knots (34.5 mph or 55.5 km/h)

Crew Members

The Rising Sun yacht typically employs a large crew to ensure top-notch service and maintenance. The exact number can vary but may range from around 45 to 55 crew members, including officers, chefs, stewards, and technical staff.

Positions of Crew Members

The crew members on Rising Sun are organized into various departments, including deck, engineering, interior, and more. Specific positions can include captain, first officer, stewardesses, engineers, deckhands, and chefs, among others.

Number of Rooms

Rising Sun boasts an impressive number of rooms and accommodations, including numerous staterooms and suites for guests. While the exact count can vary, it typically offers accommodations for around 16 to 18 guests.

Other Amenities

Rising Sun offers a wide range of luxurious amenities, including:

- Multiple dining areas for formal and casual dining experiences.

- A stunning swimming pool with jacuzzi features on the deck.

- A basketball court that can be converted into a helipad.

- A dedicated cinema room for entertainment.

- An on-deck bar for social gatherings.

- A gymnasium and spa facilities for guests to relax and stay active during their voyage.

- A high-quality audio-visual entertainment system throughout the yacht.

- A library and study area for quiet moments.

Support Vehicles

Super yachts like Rising Sun often come equipped with support vessels, such as smaller boats and jet skis, for various recreational activities and transportation to and from shore.

Additional Information

- Rising Sun is equipped with state-of-the-art navigation and communication systems to ensure safety and efficient travel.

- The yacht’s interior is designed with opulent materials, including marble and rare woods, adding to its luxurious atmosphere.

- It has a range of environmental and sustainability features, including advanced waste management and energy-efficient systems.

If you want to explore other mega yachts CLICK HERE

Or if you feel lucky and you think that you can find Rising Sun on a map, CLICK HERE to visit our Live tracking map for luxury yachts and other vessels.

Related Images:

Share this with your friends:.

- Yacht Tracking Map Find mega yacht

- Fun Map Map The World

- Privacy Policy

- Entertainment

- Latest Mortgage Rates

- Credit Cards

- Restaurants

- Food & Drink

- Lamborghini

- Aston Martin

- Rolls Royce

- Harley Davidson

- Honda Motorcycles

- BMW Motorcycles

- Triumph Motorcycles

- Indian Motorcycles

- Patek Philippe

- A. Lange & Söhne

- Audemars Piguet

- Jaeger-LeCoultre

- Vacheron Constantin

- Electronics

- Collectibles

A Closer Look at the $200 Million Rising Sun Superyacht

There are a few different categories of yachts in the world. As a yacht enthusiast you might hear a few different terms being thrown around in the descriptions, such as Super yacht up to 100 feet in length or Mega yacht up to 300 feet. These are the larger water craft and there is even a giga yacht which are those that are over 300 feet in length. With this in mind, the Rising Sun, which is often referred to as a Super yacht far exceeds the parameters set for the classification, so if we're going to be particular about the classification, we'd call it a Giga yacht. However it's categorized, the Rising Sun is one of the most amazing private yachts afloat and we're going to take a closer look at the features which make this multi-million dollar ship so special.

Rising Sun Yacht built by Lurssen: A Celebrity Choice

This yacht has hosted some of the most celebrated personalities in the film and record industry as well as the political arena. Barack and Michelle Obama were seen vacationing on the Rising Sun in 2017, and it's also hosted Hollywood stars including Oprah Winfrey , Julia Roberts , Leonardo DeCaprio, Tom Hanks and others. The co-founder of Dreamworks, film producer and record executive David Geffen is the owner of the Rising Sun, which ranks as the 9th largest yacht in the world, currently. Depending on which source you consult, the cost to build this giant is estimated to be $200 million and some have it as high as $400 million but we believe that the base cost was the latter and the extra figures come from upgrades .

The history of the Rising Sun

The Rising Sun is the commissioned craft of its first owner Larry Ellison, who partnered with David Geffen and is the current CEO of the Oracle Corporation. He ordered the building of the ship from the German shipbuilding company Lürssen . The Rising Sun is the design of Jon Bannenberg, who has since passed away. The ship was delivered to Mr. Ellison in 2004, who shared ownership with David Geffen until 2010, when he decided that it was too large, so he sold his share to Geffen, who is now the sole owner of the yacht and Ellison bought a smaller yacht.

Specifications and details

The Rising Sun yacht is constructed of a strong aluminum superstructure with a displacement steel hull and teak decks, in accordance with Germanischer Lloyd classification society rules. The ship requires 4 MTU 12,061 horsepower diesel engines to propel it though the water. The average cruising speed is 26 knots and the top speed of the ship is 30 knots. To make the yacht more comfortable and safe in rough waters, it is fitted with zero speed stabilizers for times when she is at anchor. The Rising Sun measures 453.97 ft in length with a 62.34 ft beam, a draft of 16.08 ft and gross tonnage of 7841 tons. The exterior was designed by Bannenberg & Rowel and the interior by Seccombe Design. It was built by Lurssen and refit in 2004 and 2011. At the time of the sale it was the 6th largest yacht in the world, but other new superyachts have displaced it to the 9th position.

Luxury amenities

It takes a crew of 45 to maintain and operate this massive vessel and they are housed in 30 cabins. The guests are housed in 8 cabins which can accommodate between 16 and 18 guests comfortably. The yacht has been designed with more than 8,000m² of living space, allowing for larger gathering areas as well as plenty of places to find privacy from the crowd of guests. There are a total of five decks with 82 rooms aboard the yacht. Some of the luxury amenities include a spa and gym so guests don't need to miss out on their daily workout routines. The Rising Sun is also quipped with a lift/elevator to take guests between the five decks. For practicality so guests/owners can come and go from any location, there is also a helipad on board. For fun in the sun there is a swimming pool as well as underwater lights for excellent illumination, and a sauna for relaxation. The ship also features air conditioning throughout the 82 rooms so guests can achieve the optimal room temperatures, even on hot days at sea, and there is also a Tender Garage, as well as a Cinema large enough to accommodate all guests for entertainment.

Final thoughts

The Rising Sun has only had two owners since it was built in 2004. Co-owners Larry Ellison and David Geffen shared it for a period of time, then Ellison sold his share to Geffen who is now the sole owner. The yacht was once the sixth largest yacht in the world, but is still considered a wonder coming in at ninth place. It's packed to the hilt with luxury amenities and there is plenty of space aboard with five decks and 82 rooms. The ship which cost $200 million to build is now valued somewhere between $3 and $4 million, and it has only increased in value with the passage of time and no doubt numerous upgrades to suit the preferences of the owner. It's served as the vessel that provides a source of recreation for some of the most famous people in the world including some of our most beloved Hollywood stars and even a former president and first lady. The Rising Sun is truly one of the most magnificent yachts that has ever been created, and those who are fortunate enough to be invited on board are in for a top notch luxury experience.

Written by Dana Hanson

Related articles, a closer look at the royal huisman's striking blue superyacht phi.

The Top 20 Celebrity Yachts in The World

A Closer Look at David and Victoria Beckham's Yacht SeaFair

17 Most Expensive Yachts in the World

A closer look at tankoa's t500 tethys, a closer look at x-yachts new x49e electric sailing boat, check out camper and nicholsons international's 120 ft tecnomar superyacht "lucy", sirena's new fully customizable 78-foot yacht.

Wealth Insight! Subscribe to our Exclusive Newsletter

Hollywood billionaire David Geffen has been self-isolating on his superyacht in the Caribbean during the coronavirus pandemic. Take a look at the $590 million yacht.

- Billionaire David Geffen is in the hot seat for a "tone-deaf" Instagram post about isolating on his yacht, Rising Sun, in the Caribbean, The Guardian reported .

- Geffen reportedly paid $590 million for the yacht, which previously belonged to Oracle founder Larry Ellison .

- Rising Sun is something of a playground for the rich and famous, as Geffen has been known to host celebrities like Oprah Winfrey and Leonardo DiCaprio on board.

- Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos was spotted on the superyacht last summer.

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories .

Billionaire and entertainment mogul David Geffen is in the hot seat this week for a "tone-deaf" Instagram post about isolating on his $590 million yacht in the Caribbean during the coronavirus pandemic, The Guardian reported .

On Saturday, Geffen posted photos showing his superyacht, Rising Sun, in the Grenadines with the caption, "Sunset last night. Isolated in the Grenadines avoiding the virus. I hope everybody is staying safe." The backlash on Twitter was prompt, with people calling his post "shameful" and out of touch, reported Business Insider's Katie Warren . He appears to have since deactivated his Instagram .

It's the same yacht that Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos was spotted on in the Balearics, Spain, last summer. In a photo posted to Geffen's Instagram , Bezos was seen with his girlfriend, Lauren Sanchez; the supermodel Karlie Kloss; and former Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein.

But Bezos and crew aren't the first to cruise the high seas with Geffen, who appears to love hosting celebrities, musicians, and actors. Leonardo DiCaprio, Bradley Cooper, Oprah Winfrey, and Barack and Michelle Obama have also previously kicked back on Geffen's 400-foot-plus superyacht.

Here's a look at Rising Sun — and the big names who have been on board.

The entertainment mogul David Geffen, founder of DreamWorks, SKG, Asylum Records, Geffen Records, and DGS Records, owns Rising Sun. According to Forbes, he's worth an estimated $7.8 billion.

Source : Forbes

The 454-foot megayacht was originally built for Oracle founder Larry Ellison. Geffen bought a half-share in 2007 and the other half in 2010, totaling $590 million.

Source : Forbes

The exact value of the superyacht is unclear. However, a 2019 put its value at $300 million.

Source : Yacht Harbour

Rising Sun was constructed by the German shipbuilder Lurssen. Once Geffen became owner, he had the yacht refitted over a six-month period.

Source : Boat International

The yacht can accommodate 18 guests and a staff of 55 people. It even has a basketball court.

The top deck is dedicated entirely to the owner and includes a double-height cinema.

Geffen has cruised everywhere from St. Bart's and the Tobago Cays in the Caribbean to Portofino, Italy, and Ibiza, Spain, according to posts Business Insider previously viewed on his now-deactivated Instagram — but not without a few friends.

Rising Sun is a great place for entertaining. A scroll through Geffen's Instagram feed before it was deleted showed that he's hosted many a celebrity guest on board.

Oprah Winfrey, Bradley Cooper, Orlando Bloom, Katy Perry, Chris Rock, Bruce Springsteen, Mariah Carey, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Tom Hanks have all joined Geffen in cruising the high seas, according to now-deleted Instagram posts.

♥️ happiness entrepreneurs ♥️ A post shared by KATY PERRY (@katyperry) on Jul 28, 2019 at 8:57am PDT Jul 28, 2019 at 8:57am PDT

Source : Business Insider , GQ

But Geffen doesn't just invite actors and musicians on board. In 2017, Barack and Michelle Obama were spotted on board while the yacht was in French Polynesia.

Source : Business Insider

And in summer 2019, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, investment banker Lloyd Blankfein, and supermodel Karlie Kloss were spotted aboard in the Balearics in Spain.

But Geffen likely won't have any friends on board anytime soon during the coronavirus pandemic.

On Saturday, he posted a photo to his Instagram from Rising Sun. The caption read: "Sunset last night. Isolated in the Grenadines avoiding the virus. I hope everybody is staying safe."

Twitter lit up with backlash, with people calling his post "shameful" and out of touch. Geffen then deleted his Instagram.

—Robby Starbuck (@robbystarbuck) March 28, 2020

Source : Twitter

While the combined $590 million that Geffen spent to buy Rising Sun is an astronomical figure, it pales in comparison to the world's most expensive yacht. That title goes to the Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich's yacht Eclipse, which is estimated to be worth anywhere from $600 million to $1.5 billion.

Source: Business Insider

- Main content

The Best Yacht Concepts From Around The World

The Stunning Ritz Carlton EVRIMA Yacht

Gliding Across Tokyo’s Sumida River: The Mesmerizing Zipper Boat

CROCUS Yacht: An 48 Meter Beauty by Admiral

- Zuretti Interior Design

- Zuretti Interior

- Zuccon International Project

- Ziyad al Manaseer

- Zaniz Interiors. Kutayba Alghanim

- Yuriy Kosiuk

- Yuri Milner

- Yersin Yacht

- Superyachts

RISING SUN Yacht – Exceptional $400M Superyacht

RISING SUN yacht is currently the 16th largest motor yacht in the world at a length of 138.6 meters (454 ft).

She was built by Luerssen in Bremen, Germany, and launched in June of 2004.

RISING SUN yacht interior

The interior of the RISING SUN yacht was styled by Seccombe Design, a small and highly specialized design company. The 138.6 meter-long vessel was their largest project to date. She was last refitted in 2011 and fully updated to fit modern standards. The interior of RISING SUN is classically styled with lots of dark elements and wooden features.

She comes with a gym, a grand piano, multiple swimming pools, a beauty salon, and a spa which includes a sauna.

Sixteen guests can be welcomed aboard the super yacht’s eight suites. A further 45 crew members find space in 30 cabins below the deck.

Specifications

The RISING SUN yacht is powered by four MTU engines which allow her to reach top speeds of up to 30 knots although her cruising speed lies at 26 knots.

She was built by Luerssen , one of the most famous shipyards for luxury yachts in the world. Her total volume lies at 7841 tons making her one of the largest motor yachts in the world not only by length but also weight.

Her beam measures 19 meters (62.4 ft) and her draft is 4.85 meters (15.1 ft). The built-in at-anchor stabilizers allow her guests to be comfortable even during rough seas.

The exterior of the RISING SUN yacht was developed by the superyacht designers Bannenberg & Rowell.

Dickie Baneberg’s father was one of the most legendary designers of all time in the industry, sometimes even called the father of yacht design.

His son is continuing his legacy and elements of Jon Bannenberg’s style can still be recognized in this work. With her many separate windows RISING SUN almost looks like a small cruise ship.

She is all-white, in classical yacht design with a steel hull and aluminum superstructure. In addition to her covered decks, she features a large open-air space at the bow as well as one at the aft of the vessel.

The RISING SUN yacht originally cost an estimated US $200 million when she was launched in 2004. However, due to refits and sales RISING SUN is now valued at a price of US $570 million.

Her annual running costs lie somewhere between US $25 and 40 million.

Do you have anything to add to this listing?

- Bannenberg & Rowell Design

- Bannenberg Design

Love Yachts? Join us.

Related posts.

- Most Popular

AZZAM Yacht – The World’s Biggest Superyacht is 180m Long

Satori Yacht – Unparalleled $75 M Superyacht

SUNRAYS Yacht – Exquisite $150M Superyacht

YALLA Yacht – Impressive $80M Superyacht

The global authority in superyachting

- NEWSLETTERS

- Yachts Home

- The Superyacht Directory

- Yacht Reports

- Brokerage News

- The largest yachts in the world

- The Register

- Yacht Advice

- Yacht Design

- 12m to 24m yachts

- Monaco Yacht Show

- Builder Directory

- Designer Directory

- Interior Design Directory

- Naval Architect Directory

- Yachts for sale home

- Motor yachts

- Sailing yachts

- Explorer yachts

- Classic yachts

- Sale Broker Directory

- Charter Home

- Yachts for Charter

- Charter Destinations

- Charter Broker Directory

- Destinations Home

- Mediterranean

- South Pacific

- Rest of the World

- Boat Life Home

- Owners' Experiences

- Interiors Suppliers

- Owners' Club

- Captains' Club

- BOAT Showcase

- Boat Presents

- Events Home

- World Superyacht Awards

- Superyacht Design Festival

- Design and Innovation Awards

- Young Designer of the Year Award

- Artistry and Craft Awards

- Explorer Yachts Summit

- Ocean Talks

- The Ocean Awards

- BOAT Connect

- Between the bays

- Golf Invitational

- Boat Pro Home

- Superyacht Insight

- Global Order Book

- Premium Content

- Product Features

- Testimonials

- Pricing Plan

- Tenders & Equipment

Iconic yachts: Inside the design journey of the 138m Lürssen superyacht Rising Sun

Rising Sun was the last yacht that ever came from designer Jon Bannenberg’s drawing board (literally, as the office was then an almost CAD-free zone), and one that he was destined never to see completed.

To a degree, Rising Sun represented a back-to-basics approach and a final opportunity to work with Lürssen’s lean destroyer-type hull, which had been the platform 30 years earlier for Carinthia V and Carinthia VI (now named The One ). The similarities ended there. Rising Sun experimented with extensive use of structural glass for a clean and stripped-down profile that involved Lürssen and its sub-contractors working on engineering and systems.

Jon Bannenberg’s appointment to design Rising Sun came out of the blue after Larry Ellison had commissioned a number of studies from different designers. None seemed to have the impact that he wanted until Jon Bannenberg unveiled his initial study model one morning in London over a couple of lattes. Things moved quickly after that, and they reached an agreement in two emails without even a hint of a lawyer being involved. LE120 became the project’s codename but it did not need Enigma codebreaking skills among the yachting community to work out the vessel’s length and who had commissioned her.

Jon Bannenberg worked on many study models in the early months, including a colossal version that was shipped to Lürssen and used for an initial presentation meeting with the principal sub-contractors. The basic form did not change much from his first drawing. Among the spectacular concepts was a suspended, tube-like walkway through the main machinery spaces for visitors to see exactly what drove her at speeds of 30 knots, and an exposed Z frame structure separating the tender launching areas. This was monumental in scale but sculptural and simple to fabricate.

The exposure of structure was one of the overarching themes of his Rising Sun design – no more clearly apparent than in the web frames of the superstructure, into which the full-height glass panels were set. The initial intent was to have these in raw finished aluminium, but this subsequently got ‘value engineered’ into a metallic paint finish.

His general arrangement layouts of Rising Sun gave spacious guest cabins direct access to the exterior side decks, protected from the weather by 45-degree indents in the superstructure. There was so much space to play with that the top deck was given over entirely to owner use, while a double-height cinema was embedded like the stone of an avocado, with the corridor arcing gently around it. And, of course, a basketball court was obligatory.

All in all, Jon Bannenberg’s original concept for Rising Sun survived relatively intact after his death. The yacht divided opinion, like many of his designs, and her sheer scale – eventually growing to 138 metres – made even Larry Ellison pause for thought. But she is certainly a Bannenberg original, and somehow neatly completed the circle that started with Carinthia V and Lürssen some 30 years earlier.

More about this yacht

More stories, most popular, from our partners, sponsored listings.

- Weather

Search location by ZIP code

Massive yacht turns heads along portland waterfront.

The Rising Sun is one of the largest in the world

- Copy Link Copy {copyShortcut} to copy Link copied!

GET LOCAL BREAKING NEWS ALERTS

The latest breaking updates, delivered straight to your email inbox.

Maine is known for its waterfront, and places like Portland are certainly no stranger to massive cruise ships and luxury yachts.

But a boat that has been docked in Portland for the last several days is certainly turning some heads.

The "Rising Sun" is owned by billionaire media mogul David Geffen. The so-called giga-yacht is one of the 20 largest yachts in the world.

It is 452 feet long, and five stories high with 82 rooms, a spa, a movie theater, a wine cellar and a full-sized basketball court. It staffs a crew of 45 people.

Many people have been heading to the Portland waterfront just to get a look.

Please use a modern browser to view this website. Some elements might not work as expected when using Internet Explorer.

- Landing Page

- Luxury Yacht Vacation Types

- Corporate Yacht Charter

- Tailor Made Vacations

- Luxury Exploration Vacations

- View All 3618

- Motor Yachts

- Sailing Yachts

- Classic Yachts

- Catamaran Yachts

- Filter By Destination

- More Filters

- Latest Reviews

- Charter Special Offers

- Destination Guides

- Inspiration & Features

- Mediterranean Charter Yachts

- France Charter Yachts

- Italy Charter Yachts

- Croatia Charter Yachts

- Greece Charter Yachts

- Turkey Charter Yachts

- Bahamas Charter Yachts

- Caribbean Charter Yachts

- Australia Charter Yachts

- Thailand Charter Yachts

- Dubai Charter Yachts

- Destination News

- New To Fleet

- Charter Fleet Updates

- Special Offers

- Industry News

- Yacht Shows

- Corporate Charter

- Finding a Yacht Broker

- Charter Preferences

- Questions & Answers

- Add my yacht

NOT FOR CHARTER *

This Yacht is not for Charter*

SIMILAR YACHTS FOR CHARTER

View Similar Yachts

Or View All luxury yachts for charter

- Luxury Charter Yachts

- Motor Yachts for Charter

- Amenities & Toys

RISING SUN yacht NOT for charter*

138.6m / 454'9 | lurssen | 2004 / 2011.

Owner & Guests

Cabin Configuration

- Previous Yacht

Special Features:

- Elevator for easy access between floors

- State-of-the-art cinema

- Swimming pool

- Germanischer Lloyd classification

- Cruising speed of 26 knots

The 138.6m/454'9" motor yacht 'Rising Sun' was built by Lurssen in Germany at their Bremen shipyard. Her interior is styled by design house Seccombe Design and she was delivered to her owner in June 2004. This luxury vessel's exterior design is the work of Bannenberg & Rowell and she was last refitted in 2011.

Guest Accommodation

Rising Sun has been designed to comfortably accommodate up to 18 guests in 9 suites. She is also capable of carrying up to 45 crew onboard to ensure a relaxed luxury yacht experience.

Onboard Comfort & Entertainment

Her features include a movie theatre, beauty salon, elevator, underwater lights, gym and air conditioning.

Range & Performance

Rising Sun is built with a steel hull and aluminium superstructure, with teak decks. Powered by 4 x diesel MTU (20V 8000 M70) 20-cylinder 11,149hp engines running at 1150rpm, she comfortably cruises at 26 knots, reaches a maximum speed of 30 knots. Rising Sun features at-anchor stabilizers providing exceptional comfort levels. Her water tanks store around 100,000 Litres of fresh water. She was built to Germanischer Lloyd classification society rules.

*Charter Rising Sun Motor Yacht

Motor yacht Rising Sun is currently not believed to be available for private Charter. To view similar yachts for charter , or contact your Yacht Charter Broker for information about renting a luxury charter yacht.

Rising Sun Yacht Owner, Captain or marketing company

'Yacht Charter Fleet' is a free information service, if your yacht is available for charter please contact us with details and photos and we will update our records.

Rising Sun Photos

Rising Sun Awards & Nominations

- International Superyacht Society Awards 2019 Best Refit Finalist

NOTE to U.S. Customs & Border Protection

Specification

M/Y Rising Sun

SIMILAR LUXURY YACHTS FOR CHARTER

Here are a selection of superyachts which are similar to Rising Sun yacht which are believed to be available for charter. To view all similar luxury charter yachts click on the button below.

115m | Lurssen

from $2,822,000 p/week ♦︎

92m | Feadship

from $1,500,000 p/week

Carinthia VII

97m | Lurssen

from $1,520,000 p/week ♦︎

95m | Lurssen

from $1,737,000 p/week ♦︎

90m | Oceanco

from $1,303,000 p/week ♦︎

107m | Olympic Yacht Services

from $2,171,000 p/week ♦︎

97m | Feadship

136m | Lurssen

from $4,342,000 p/week ♦︎

108m | Benetti

from $1,954,000 p/week ♦︎

122m | Lurssen

from $3,000,000 p/week

91m | Lurssen

from $1,400,000 p/week

93m | Feadship

As Featured In

The YachtCharterFleet Difference

YachtCharterFleet makes it easy to find the yacht charter vacation that is right for you. We combine thousands of yacht listings with local destination information, sample itineraries and experiences to deliver the world's most comprehensive yacht charter website.

San Francisco

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on Instagram

- Find us on LinkedIn

- Add My Yacht

- Affiliates & Partners

Popular Destinations & Events

- St Tropez Yacht Charter

- Monaco Yacht Charter

- St Barts Yacht Charter

- Greece Yacht Charter

- Mykonos Yacht Charter

- Caribbean Yacht Charter

Featured Charter Yachts

- Maltese Falcon Yacht Charter

- Wheels Yacht Charter

- Victorious Yacht Charter

- Andrea Yacht Charter

- Titania Yacht Charter

- Ahpo Yacht Charter

Receive our latest offers, trends and stories direct to your inbox.

Please enter a valid e-mail.

Thanks for subscribing.

Search for Yachts, Destinations, Events, News... everything related to Luxury Yachts for Charter.

Yachts in your shortlist

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

- Newsletters

The Good Life Aquatic

By Mark Seal

‘Have you ever seen anything so cool in your life? ” Jamie Edmiston, the 29-year-old super-yacht broker, has to shout, for we are in a Eurocopter EC130 over the ocean off Antibes, on our way to a yacht called Senses. It’s May of last year, and all the giant luxury boats are clustered on the Côte d’Azur for the Cannes Film Festival and the Grand Prix in Monte Carlo. Having wintered in Palm Beach, the Caribbean, and beyond, the crews have streaked across the Atlantic while their employers jetted over on their Gulfstreams, Citations, Boeing Business Jets, and Bombardier Global Expresses.

Edmiston and I have taken off from the so-called Quai des Milliardaires (“Dock of the Billionaires”) at the International Yacht Club of Antibes, which was begun in 1999 to berth the big boats. As we fly over the seagoing behemoths, Edmiston points certain ones out: the Leander, parking-lot tycoon Sir Donald Gosling’s stately home on water; Aussie Rules, built by golf star Greg Norman and recently sold to Miami Dolphins owner Wayne Huizenga, which has a swimming pool, a movie theater, and a dozen smaller boats on board; Sokar, the pride of Harrods owner Mohamed Al Fayed, on which his son, Dodi, and Princess Diana spent their last days, in 1997.

We’re 12 miles offshore, the minimum requirement for a helicopter to land on a boat along the Riviera, approaching Senses, a 194-foot exploration yacht, one of the largest in the world, with interiors by Philippe Starck and an abundance of “toys,” a yachting term that can mean anything from a Jet Ski to a submarine. Edmiston cries, “Look at the dolphins!” The copter tilts sideways, and I can see dozens of dolphins, leaping into the air and leading us straight toward the boat, as if they had been sent to fetch us. When we land on the fourth and uppermost deck, the yacht’s co-owner, Alan Gibbs, 65, the New Zealand inventor, takeover artist, and telecommunications mogul, is standing there in his bathing suit with two ravishing young women in string bikinis at his side—Emma, his daughter, a neuroscientist, and Sandra Baker, his Tahitian girlfriend.

Gibbs leads us to the sundeck for lunch. “It’s about freedom to, not freedom from, ” he says to explain the thrill of owning a yacht. “We’re free to do, free to go, is how I see it. We’re not going to fly to the moon from here. But it would be hard to find a better way to explore the earth than on this.”

The boat beneath us is a $40 million Goliath with a 120-ton fuel tank that costs $80,000 to fill and can keep the yacht at sea for a good part of the summer. Gibbs has taken Senses halfway around the world. “We were the first large yacht that actually visited Tunisia,” he says. “They couldn’t quite cope with it. The helicopter just drove them nuts—that some private person would have a ship that looked like the navy and wanted to fly all over Tunisia in a helicopter.”

Suddenly he shouts, “Get the toys in the water!” There is an instant buzz of walkie-talkies, and 14 crew members scurry out. Up goes the yacht’s helicopter, and down go the 42-foot tender, the 32-foot sailing yacht, and six Jet Skis. Then Gibbs yells, “Launch the Aquada!” A hatch opens, and the world’s first high-speed amphibious car, Gibbs’s invention, seven years in development and coming to the market soon, glides down a ramp into the sea. As its wheels retract, it turns into a speedboat. Gibbs drives, and the women sit atop bucket seats, spume wetting their hair as they seem to push the limits of extravagance. Back on board minutes later, Gibbs says, “That was really James Bond stuff out there. But Bond is only mucking it up. We’re really doing it!”

‘Ever larger boats have replaced palaces, estates, and art as the ultimate symbols of wealth, which is not altogether surprising, given the fleeting and disposable nature of our society,” says Mark Getty, the son of Sir J. Paul Getty Jr., as he shows me around Talitha G, which was launched in 1929 by the head of Packard, sold to the chief of Woolworth’s, requisitioned by the U.S. Navy during World War II, rescued by Saturday Night Fever movie producer Robert Stigwood, and immaculately restored by J. Paul Getty Jr. in 1993. Named for his second wife, Talitha G has six staterooms, open fireplaces, Lalique glass doors, period art and furnishings, and the latest technology. Hollywood superstars and captains of industry can charter her for $350,000 a week, excluding gas and gratuities.

It’s the day of the Grand Prix in Monte Carlo, and from *Talitha’*s aft deck Mark Getty and I are gazing out on a sea full of super-yachts. We can hear the Formula One race cars buzzing around curving hillsides above us and the crowd’s cheers. But the bigger race is definitely here in the harbor, Port Hercule, where 111 boats pack every available slip—at a cost of $25,000 to $50,000 a week each—while dozens more that can’t find space or are just too big to fit are moored around the harbor’s rim. As big as cruise ships, super-yachts have names to match— Giant, Kingdom 5KR, Hedonist, Huntress, Limitless, Seawolfe, Passion, Nectar of the Gods, Naughty by Nature, Big Roi.

Sir J. Paul Getty Jr.'s Talitha G , restored in 1993 by the late Jon Bannenberg, long considered the world's foremost yacht designer.

In order to see them up close, I descend three decks and get into a Wally Tender, the motorboat used to ferry owners, guests, crew, and supplies from ship to shore and yacht to yacht. Like everything else in yachting, the Wally Tender is over the top; this $670,000 propeller-powered Batmobile is considered a necessary accessory by everyone from the designer Valentino to Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi. I’m traveling with Luca Bassani, the owner of Wally Yachts, who has revolutionized yachting, first with sailing yachts and then with power ones. He slams the tender into gear, and the boat almost levitates, quickly bringing us right up alongside the huge vessels.

They rise up from the ocean like monoliths. There’s the vanilla-colored, $100 million Pelorus (378 feet), one of four super- yachts owned by the Russian oil billionaire Roman Abramovich. Pelorus is equipped with bulletproof glass, a missile-detection system, two helicopters, a submarine, and high-intensity “paparazzi lights,” designed to obliterate the film of any interloping photographer. Beyond that is Lady Moura (344 feet), owned by Saudi billionaire Dr. Nasser al-Rashid, with an 80-member crew, a fully equipped hospital, an onboard sand beach, and a 59-foot dining table. Next is Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos’s 379-foot Atlantis II, which has rarely left the harbor since his death, in 1996. Then comes Delphine, launched in 1921 by American automobile magnate Horace Dodge and requisitioned by Franklin Roosevelt for meetings with Winston Churchill and Vyacheslav Molotov during World War II; restored, it rents for $60,000 a day.

Moored outside the port is Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s Octopus, making its debut in the Mediterranean, having just sailed from New Orleans, where Allen used the boat to promote his company’s new software at a convention of cable-TV executives. Built at a cost that reportedly escalated from $250 to $400 million, with a crew of 60 that includes former navy SEALs, Octopus is, at 413 feet, the world’s largest privately owned yacht, so huge that the lifeboats strapped to its side look like tiny toys. Anchored by means of a dynamic positioning system that enables the captain to stop with perfect precision, it’s a skyscraper with seven decks, two helicopter landing pads, a swimming pool, a basketball court, an infirmary, a garage, a movie theater, and, in its belly, a port to house many of the 14 tenders. These include a custom-built submarine that can remain underwater with 10 people for two weeks and a remote-controlled robot for exploring the ocean floor. There’s a concert space for 260, a massive guitar sculpture that rises up through the entire height of the boat, and a recording studio, which is a second home to musicians ranging from Dan Aykroyd to Robbie Robertson. On the lowest level is an observation lounge with a glass bottom and stadium-strength lighting that illuminates the depths, for watching sea creatures.

By Kase Wickman

By Erin Vanderhoof

By Chris Murphy

This colossus has everything on it but torpedoes, which Allen declined when the builder suggested them for security. Meanwhile, Allen’s great rival, Oracle’s Larry Ellison, has just completed Rising Sun, 47 critical feet longer than Octopus, a new record for length. As J. P. Morgan once said when asked about the cost of his yacht, Corsair III, which, at 300 feet and with a crew of 70, was the world’s largest in the early 1900s, “If you have to ask how much it costs, you can’t afford it.”

In the shadow of these monsters in the harbor is an array of smaller yachts, which are still big enough to be classified as “mega-,” or “super-,” a category that includes all powerboats and sailboats more than 80 feet long, according to Diane Byrne of Power & Motoryacht magazine. There are between 5,000 and 6,000 super-yachts in the world, and the number is growing steadily—622 were launched in 2003 alone.

“It’s a grand traveling home,” says Dr. Charles Simonyi, one of the pioneers of Microsoft and a driving force behind the invention of its Excel program, as he relaxes on the sundeck of *Skat—*Danish for “my darling.” A slate-gray, 231-foot vessel that is sometimes mistaken for a battleship, it serves as the bachelor’s home and office six months of the year. Decorated with Victor Vasarely and Roy Lichtenstein paintings and Arne Jacobsen “egg” chairs, Skat is the result of Simonyi’s failed search for satisfying apartments. “I tried Montréal, I tried Monte Carlo, I tried Copenhagen,” he says. But why, he finally decided, join the dogfight for locations and suffer the indignities of local taxes, constant maintenance, and zoning restrictions when you can sail into the heart of the capitals of the world on a luxurious, fully staffed fortress? “In all of the Scandinavian capitals—Oslo as well as Copenhagen and Stockholm—we are always docked next to the king’s or queen’s palace,” he says. “We are occupying the best real estate, and I have the nicest bathroom and a fantastic restaurant.” Although Simonyi insists that he uses Skat as a base to run his businesses, life on board most boats is pretty sybaritic—breakfast until noon, lunch until 3, cocktails at 6, dinner until 12, and drinks until dawn.

When the Grand Prix winner is announced, every yacht in the harbor blasts its horn, and they sound like an armada of whales, drowning out the applause coming from Monte Carlo’s natural amphitheater above. Within hours most of the boats will depart, untangling themselves from one another’s anchor lines and heading out to sea.

If you don’t own a yacht, you can always charter one, at prices ranging from $203,000 a week for the 175-foot Perfect Prescription (which Jaguar leased and lent to Brad Pitt, George Clooney, and Matt Damon during the filming of Ocean’s Twelve ) to $850,000 a week for Annaliesse, a 279-footer with 18 staterooms (instead of the usual 12). On the day of my visit, Annaliesse has been chartered for a wedding. Lionel Richie is on board to serenade the party, and the bride and groom and 100 guests arrive by helicopter, all of them dressed in white bathrobes.

With the exception of Tiger Woods, who owns a 155-foot boat he christened Privacy, celebrities tend to lease or rent. Denzel and Pauletta Washington rent a yacht almost every summer; so do Magic Johnson, rap star Jay-Z, Steven Spielberg and Kate Capshaw, and Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson. If you can’t charter, you can visit friends who do or, as they say in the yachting world, go hopping. “Yacht-hopping,” explains fashion model Naomi Campbell, who took her first cruise a decade ago, on Mohamed Al Fayed’s yacht. When I meet her, she’s staying on Formula One racing impresario Flavio Briatore’s Lady in Blue. Today, she says, she’ll hop from Lady in Blue to Valentino’s TM Blue One to the Brazilian party boat called Bossa Nova. “Boat to boat,” she says. “It’s disgusting. When I say, ‘yacht-hopping,’ I mean I go to say hi to my friends.”

Darwin Deason with his partner, Katerina Panos and their crew and security force, ready to greet guests for cocktails.

I’ve been invited to spend some time on the Apogee, at 205 feet the 62nd-largest yacht in the world, according to *Power & Motoryacht’*s 2004 rankings. It cost $50 million and charters for $320,000 a week. “Welcome to the Apogee, ” says the steward who scoops up my luggage from the dock at Cagnes sur Mer and deposits it in a tender. Speeding through the soup of Jet Skis, minnow speedboats, and midsize yachts, I can see the Apogee and its owner, Dallas-based international computer-services titan Darwin Deason, and his glamorous partner, Katerina Panos, waving from the aft deck. They are flanked by the 17-member crew, standing in two neat lines.

They greet every guest this way, 12 of us all together, with the whole crew shaking our hands and introducing themselves before they escort us to the six guest staterooms, each named for a Greek island. Our bags are unpacked for us, and Deason gives us a tour of the interior’s 26,000 square feet: the wood-paneled upstairs and downstairs saloons, the Apogee Club Bar, the disco dance floor with a Wurlitzer juke-box, the formal dining room—all the way up to the fourth-level sundeck, where we forgo the fully equipped gym and the 12-person Jacuzzi to bake in the sun until cocktails are served. By then the twin Caterpillar engines are purring and we’re cruising the five miles to Monte Carlo.

‘A yacht is a demonstration of wealth,” says yacht broker Nicholas Edmiston, Jamie’s father. Formerly C.E.O. of the venerable yacht-sales-and-charter company Camper & Nicholsons, Edmiston created his own business in 1996 to focus on selling and chartering “really big yachts,” which he says means upwards of 150 feet. Business is booming, with yacht construction up 22 percent over last year and a $950 million increase in sales, according to industry experts. “There has been a huge expansion in big yachts over the past six to seven years, with even bigger ones on the drawing board,” says Edmiston. “More than ever in history—because we’ve got more rich people. A yacht is probably the most expensive single purchase that anyone is ever going to make.”

Nothing else comes close. A jet? A mansion? They are mere starter kits for yacht enthusiasts. “There was a huge prime estate that just came on the market in England—3,600 acres, the most beautiful grade-one house, designed by Sir Christopher Wren’s protégé. Immaculate. And that is $75 to $80 million. I’m selling yachts today for $150 to $200 million.” He looks out over the port of Monte Carlo. “I always say to people, ‘Never spend more than 10 percent of your net worth on buying a yacht.’ So the guy that wants to buy a yacht for $25 million is worth $250 million.”

Time is of the essence, Edmiston says, because once you have enough money to buy a boat, chances are you don’t have nearly enough years left to enjoy it. “From the beginning of the planning to taking delivery is three to four years,” he says. “So if you’re the 67-year-old billionaire standing on the dock here with a young woman on your arm and she says, ‘Honey, I’d love one of those!,’ can he risk waiting four years to get it built? Or is it better to say to the guy who just paid 50 million for a new yacht, ‘How about if I give you 65?’ I know what I’d do.” A new yacht from a German or Dutch shipyard can appreciate approximately 25 percent the minute it hits the water, he says.

“Roughly 10 percent of the price of the yacht is what it costs every year to run it,” adds Edmiston, listing the costs: captain and crew (plus helicopter pilots, personal maids, guides, masseuses, hairdressers, etc.), insurance, harbor fees, maintenance, fuel—which industry experts say can run as high as $300,000 for a summer’s fill-up for Paul Allen’s Octopus. Edmiston motions across the harbor to a 300-footer. “To paint a yacht like that is around $4 to $5 million,” he says. “Of course, you don’t have to do it every year.”

Most owners charter their yachts, but the super-rich never do; they want them in constant readiness. “I was on a big yacht down in Sardinia not long ago, and the owner was complaining that he couldn’t get any decent fresh fruit,” says Edmiston. “It’s a nice place, Sardinia, but not really noted for agriculture. So there was a helicopter on the yacht, which I sent to the market in Cannes, a 400-mile round-trip. He got his raspberries and strawberries and was very happy.” The fruit probably cost $4,000 in fuel and other expenses. “Who cares?” says Edmiston. “What I cared about is that the owner got what he wanted.”

‘This yacht took two years in dreaming, three years in building,” says Mexico City industrialist Carlos Peralta, standing on his seventh boat, a Swarovski-crystal-encrusted fantasy called Princess Mariana, for his wife. It has six decks, six bars, 1,600 movies, 16,000 pre-programmed songs, three chefs, a cellar with 2,000 bottles of wine and 1,000 bottles of tequila, a laundry, a wall that opens to turn a bedroom into a terrace, and such high-tech features as fingerprint-identification pads to secure staterooms and other areas. We’re bobbing in the bay off the Hôtel du Cap, surrounded by yachts, including Barry Diller’s two-masted ketch, The Mikado. Peralta tells me that covetous Saudi princes have been circling his boat all week in powerboats, and that he has turned down several offers to sell it at an enormous profit. “It’s the most expensive thing you can build,” he says, “but it gives you pleasure like nothing else.”

“I’ve bought a second boat that I call the Lady Lola Shadow, a 186-foot, 20-year-old supply vessel, and I’ve just loaded her with toys,” says Idaho-based newspaper magnate Duane Hagadone, who, in commissioning his 205-foot Lady Lola, admonished the designers, “Give me some sizzle!” The result includes the 18-hole Lady Lola Golf Club, where golfers hit floating golf balls off a retractable tee on the sundeck toward 18 floating pins and have their games tracked by satellite and displayed on a television screen. “The second boat follows along behind the Lady Lola. I’ve got a custom-made wooden boat, a 150-mile-per-hour speedboat, a submarine, landing boats, canoes, kayaks—17 boats, plus the helicopter, in the Lady Lola fleet.”

“Most people don’t even know they want a yacht,” international boat broker Steve Kidd says of his clientele, powerhouses who think they’ve done it all until someone leads them onto a yacht and into another dimension. “Fifty kilograms of Iranian beluga at $500,000, 300 bottles of Dimple scotch, 300 bottles of Johnny Walker Black, 50 cases of champagne, 40 pounds of foie gras, close to 100 pounds of Niman Ranch beef—bill just shy of a million,” says a provisioner of one boat owner’s memorable order. London-based designer Donald Starkey adds, “I’ve personally put on one yacht alone a Picasso, a Dubuffet, two Utrillos, two or three Chagalls, and more. The value of the art is probably three times the value of the yacht.” Valentino’s rep Carlos Souza says, “Whenever guests come to TM Blue One, they make sure they pack lots of cashmere, because Valentino likes the temperature subzero, the air-conditioning running full blast.” Public-relations executive Lara Shriftman tells me, “On one boat I went on, they had a different set of designer china for every single meal. The crew cleaned the boat morning, noon, and night. In the bathrooms they had 20 different kinds of shampoo in a basket for a lot of high-maintenance girls. All the linens were Pratesi—600-thread count.”

What is it about a yacht that bewitches the super-rich? “Abandonment, an immediate yes,” says the actor George Hamilton without hesitation. King Edward VIII engaged in his romance with Wallis Simpson, which led to his abdication, during a 1936 charter on a steam yacht called Nahlin. But the allure of a yacht goes beyond mere romance. Occidental Petroleum magnate Armand Hammer had three wives, but the only photograph he carried in his wallet was of his yacht, according to Nancy Holmes in her book The Dream Boats. Fiat chairman Gianni Agnelli, whose yachts included Agneta, a teak beauty with rust-colored sails, liked to say, “You can tell what a man is like only by his boat and his woman.”

After dining on Gloria and Loel Guinness’s yacht, Sarina, in the 60s, Elizabeth Taylor told Richard Burton she wanted one. “We chartered a sweet old lady, whose original name I’ve forgotten, to go to the Greek islands,” Taylor tells me, describing the dilapidated, 165-foot motor yacht built in 1906 that she and Burton bought for $200,000. They named her Kalizma, an acronym for their children Kate, Liza, and Maria, and spent a reported $2 million in restoration. “She wasn’t pretty at all on the interior—all navy and nautical trim—and yet there was something so charming about her. Richard and I fell in love with her immediately, although it meant doing a complete revamp. I hired a decorator and asked him to remove every trace of the nautical theme. We put in diesel engines and stabilizers and transformed her into a cozy, comfortable, pretty little house, very romantic and colorful. We hung our paintings in the dining saloon and put Louis Quatorze chairs in the living room. The bedroom was all yellow and white. I think it was the prettiest one we ever had. There were rooms for all the kids, and we used her as a floating home. We took her up the Thames and kept all of our dogs on board because of the quarantine laws in England. Other boats would pass by and shout that we had the largest floating kennel in the world. She gave us more pleasure and fun and was the best present we ever gave each other.”

The exterior of the yacht, Christina O .

I’m on a tender off the coast of Cap-Ferrat, sailing toward the mother ship of super-yachts, the Christina O. On this 325-foot former Canadian Navy frigate, which Aristotle Onassis bought in 1954 for $34,000 and transformed at a cost of $4 million, the Greek tycoon invented yacht culture: living on his boat for months at a time, conducting his international business empire from his master suite, seducing in his “lucky” stateroom such fabled women as Maria Callas, Greta Garbo, and Jacqueline Kennedy. “So this it seems is what it is to be a king,” Jackie Kennedy allegedly said when she first stepped onto the Christina in October 1963.

King Farouk called the Christina “the last word in opulence,” and in Jackie’s day it had a crew of 60, two French hairdressers, three chefs, a masseuse, a maid for each of the 12 staterooms, and a small orchestra. Restored for $50 million and relaunched as the Christina O in 2001 by a syndicate, the yacht was booked for a cruise for $1.54 million for two weeks during the 2004 Olympics, in Athens.

“This boat is a place of fire, burning fire, a place of romance, power, and beauty!” says Michel Blanchi, of the Christina O Partnership, as he takes me through the Callas Lounge, which has a Steinway piano in it; the Lapis Lounge, with its famous lapis lazuli fireplace; the aft deck, with the hydraulic swimming pool whose bottom rises to become a dance floor; the master suite, with a painting by Renoir in it; and into Ari’s Bar. The handles on the bar are whales’ teeth carved with pornographic scenes from The Odyssey, and the seats are covered in the foreskins of whales’ penises. Once, leading Garbo to the bar, Onassis said, “I’m going to sit you on the biggest prick in the world.” She responded, “Mr. Onassis, you are a presumptuous man.” But she soon succumbed to his advances.

Onassis’s arch-enemy, fellow Greek shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos, not only married Onassis’s first wife, Tina, but also had the gall to compete with him in boats. When Onassis converted the Canadian frigate Stormont into the Christina, he added about 30 feet so that it would be bigger than Niarchos’s boat. When Niarchos dared to build an even bigger yacht, the Atlantis II, 55 feet longer than the Christina, with a gyroscopically controlled swimming pool whose water remained steady in rough seas, Onassis went ballistic. “I was actually there, and Onassis was furious!” says Peter Evans, author of two books about him, Ari and Nemesis. “Making phone calls around the world, to see if he could get a gyroscope adapted for his pool.” Evans smiles. “Rivalries and silliness. But it mattered to these people.”

Left, a spiral staircase on the Christina O , the Onassis yacht; Right, the notorious bar on the Christina O , with barstools covered in the foreskins of whales' penises; here Aristotle Onassis romanced such fabled women as Maria Callas, Greta Garbo, and Jacqueline Kennedy.

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis unwittingly became a bellwether of the coming craze for yacht supremacy. Having heard all about her husband’s sexual conquests on the Christina, Evans says, she almost persuaded him to sell it and design a new yacht from scratch, to be called Jacqueline. She even had the perfect designer to suggest: Jon Bannenberg.

‘Nobody needs a yacht,” Jon Bannenberg liked to say, so instead of designing yachts for practicality, he created yachts that spoke to his clients’ dreams. “He opened the floodgate of imagination,” says Jim Gilbert, the founder of ShowBoats International magazine. “When he came into the business, teak and mahogany were the only woods; blue and white and the occasional forest green were the only colors. This guy starts telling people that the same principles that apply to fashion should apply to yachts, that a yacht should stimulate all of the senses, not just the nautical senses.” One Dutch shipyard added $1 million to the cost of every Bannenberg-designed yacht for what it called “the Bannenberg factor.”

“My father never lost sight of the fact that all of us in this amazing business owe our livelihoods to people who spend, well, you know the sums, so he always made the whole process the most fantastic, exciting experience,” says Dickie Bannenberg, who has run Jon Bannenberg Ltd. since shortly before his father’s death, in 2002. A Sydney-born interior designer, Jon Bannenberg began his yacht-designing career in the early 1960s, when one of the clients of his London firm asked him what he thought about the plans for the yacht he was building. “It’s terrible,” Bannenberg said. When the client dared him to do better, Bannenberg did, and thereby embarked on a career that would span four decades and the creation of about 200 yachts. He introduced many of the features that are standard on today’s big vessels: bold hull and window shapes, split-level saloons, elevators, back stairs for crew, his-and-her baths, movie theaters, and such special touches as aft-deck garages for automobiles.

His creations included Carinthia V, for German retail tycoon Helmut Horten (who, after it sank on its maiden voyage, commanded Bannenberg to build another, bigger and faster); the Highlander, for Malcolm Forbes; the Lady Ghislaine, for British media baron Robert Maxwell (whose drowning off the yacht in 1991 remains a mystery); the Southern Cross III, for Alan Bond, the Australian industrialist who won the America’s Cup; the restoration of Talitha G, for Sir J. Paul Getty Jr.; and the 316-foot Limitless, for the Limited-store magnate Leslie Wexner.

The yacht that shocked everyone was the $70 million Nabila, which Bannenberg designed for Adnan Khashoggi. When it was launched, in 1979, it was the most opulent yacht in the world. Nabila Khashoggi, the daughter of the notorious arms dealer, meets me in a Sunset Boulevard coffee shop, in her home base of Los Angeles. In her mind the Nabila is as new as it was on the day it was launched, when she was 15. “Your baba made a boat!” she remembers being told before being led, with her eyes covered, by her stepmother, Lamia, and her nanny to a slip at the Benetti shipyard in Viareggio, Italy, where the Nabila stood on stilts. “I opened my eyes and . . . first, the size!” she remembers. “I just burst into tears.”

The 270-foot silver yacht had twin engine exhausts that resembled wings, a crew of 40, three chefs, 11 staterooms, a helicopter, a movie theater, a disco, a hospital with rotating crews of surgeons (and coffins, just in case), 296 telephones, and a fortune in revolving art. “It looked like a silver bullet,” Nabila remembers. When it was launched, hundreds of doves were released and priests and imams said prayers. Soon celebrities the world over began streaming on board, and spectators packed docks whenever the vessel pulled into port.

“I went on the Nabila with Elizabeth Taylor,” says George Hamilton. “A plane was sent for us. You would have thought you were landing on the Titanic. I don’t think Elizabeth ever wanted to leave. There were helicopters that would take you wherever; if you wanted to go to another country, you were on a plane in 15 minutes.”

Khashoggi also filled his yacht with a steady supply of beautiful, consenting young women. “Oh, definitely,” Nabila says. “My father certainly lives life to the fullest, but there’s an elegance about him. So it wasn’t like a frat party. But there were a lot of girls . . . when my stepmother wasn’t there.”

The party ended in 1989, when Khashoggi was jailed on charges of mail fraud and obstruction of justice. (He was acquitted the following year.) The first thing to go was the yacht, which he sold to Donald Trump for $25 million, after deducting $1 million on the assurance that Trump would change its name. Trump called it Trump Princess. The vessel was later sold to Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud, currently the world’s fourth-richest man, according to Forbes, who renamed it Kingdom 5-KR and who also bought Trump’s stake in the Plaza hotel. “If I wanted revenge on Donald, I’d marry this guy and get everything back,” Ivana Trump said as a joke while I was interviewing her about her own yacht, M/Y Ivana.

“Just recently, I was walking with my father on the Croisette, in Cannes, and Prince Alwaleed was sitting at a coffee shop, and the Nabila, now the Kingdom, was in the bay,” says Nabila Khashoggi. “He invited us to sit with him, so there were the three of us sitting and talking about the boat, how beautiful it was. It was very sweet, because to me Prince Alwaleed called his boat the Nabila. ”

Size matters is the message on Michael Breman’s T-shirt. Breman is sales director of Lürssen, the German shipyard, and we are bobbing on a dinghy beneath the blue bow of Paul Allen’s Octopus. Lürssen built it as well as Larry Ellison’s Rising Sun, and “Size matters” is the shipyard’s unofficial slogan. Beside Breman is Espen Øino, the Antibes-based designer of Octopus and other breakthrough yachts. They were together in Øino’s office in 1998 when the “brief,” or purchaser’s outline for a new yacht, came through Øino’s fax machine.

“Wow, this is the boat I would build if I had the money,” Breman remembers saying when he read the fax, although the two men refuse to identify the client and will discuss only the yacht, which several other designers and shipyards also made bids to build. “The client didn’t want a flashy little Mickey Mouse yacht,” says Breman. “He wanted a yacht in ship’s clothing,” says Øino.

As we circle Octopus, we can see many of the 46 antennae for every imaginable communications device as well as the two life-boats capable of rescuing the crew of 57 and 26 guests. Using the Finnish icebreaker Fennica as a model, Øino won the commission for the boat, which took three years to build. As always, Breman consulted his daughter, Josi, then seven, when he was trying to come up with a name. “Octopus,” she said, and the name stuck.

Like Allen, Larry Ellison had been stricken by the notion of the perfect yacht. Like Allen, too, he already had three yachts, including the Katana, formerly owned by Mexican TV titan Emilio Azcárraga Milmo, who pushed his designer, Martin Francis, to create a wonder, according to Øino, who worked on the boat with Francis. “He said, I am a very private person and I don’t want to be seen. But when I do go to port, I want my presence to be felt through my boat.’” The result was one of the world’s fastest and most stylish vessels, with a gas-turbine jet engine, three decks of cyclopean windows, and a 260-foot oil tanker so that El Tigre, as Azcárraga was known, could refuel at sea. Ellison bought the yacht from Azcárraga’s estate in 1998 for $25 million, spent $35 million overhauling it, and recently sold it for $68 million. But this almost perfect yacht only “drove him to contemplate what the perfect boat would be like,” Matthew Symonds writes in Softwar, his biography of Ellison. The perfect yacht would be “a proper ship, not some ghastly floating palace,” Ellison told Symonds. After interviewing every conceivable designer, Ellison walked into Jon Bannenberg’s office off London’s Kings Road in late 1999 and found the man to interpret his dreams.

Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen's 413-foot Octopus has seven decks, two helipads, and a concert space for 260.

Bannenberg didn’t live to see *Rising Sun’*s completion, but he finished the design. “It’s not only the greatest yacht that I have ever built but the greatest that has ever been built in the tradition of great yachts going back to 1810,” he told Symonds.

A longtime bitter rival of Paul Allen’s in business and yacht racing, Ellison originally called the boat by the code name LE120, for its 120-meter length (393 feet). But Ellison eventually decided to extend Rising Sun to 460 feet, 47 feet longer than Allen’s Octopus. “The boat is very beautiful—a kinetic sculpture made of metal and glass,” Ellison told Symonds. “But in a post September eleventh world it seems excessive. Now everything that’s not essential seems excessive. Beautiful gardens and beautiful boats have lost their place in the dangerous new world we live in. They no longer promise an escape from the world. There is no escape anymore.”

The race, however, is hardly over. “I’m presently designing a yacht that will outsize Rising Sun considerably, but I can’t tell you any more,” Espen Øino informs me.

In addition to luxury and size, the super-yachtsman yearns for speed. Larry Ellison almost died for it, pushing himself and his crew to sail through a hurricane-force storm in which five boats sank, six men died, and at least 55 sailors had to be rescued by helicopter, to win the Sydney-to-Hobart race in 1998.

Robert Miller, the Hong Kong based owner of Duty Free Shoppers, the international chain of stores, forsakes everything for speed. “He likes the action, the shit fight, when things get hairy,” says the captain of the Mari-Cha IV, the world’s fastest monohull racing yacht, of his boss and skipper. An engine-room fire 400 miles off the coast of Brazil, sharks in Madagascar, and hellish storms around Cape Horn are all occasions to which Miller has risen. His captain, Jef D’Etiveaud, says that the 72-year-old tycoon is happiest when awakened in his bunk—a hammock swinging in an otherwise empty cell—to steer his ship through a churning sea.

“When you get to a certain speed, she sings, she tingles, and she roars—she loves the speed,” the soft-spoken, Massachusetts-born Miller tells me as we step onto his yacht, a 140-foot sailboat emblazoned with a red dragon logo, which he commissioned at a cost of roughly $10 million for one purpose only: to break world records. (Most recently he did the San Francisco to Hawaii run in just over five days.) He can have all the comfort he needs on his other boat, Mari-Cha III, with its museum-quality art, John Munford interiors, and Honduran mahogany paneling, in the company of his Ecuadoran wife, Chantal, and their three daughters and 10 grandchildren.

On his racing yacht, Miller does whatever it takes to win: spending weeks with his crew of up to 26 (which has included his son-in-law Crown Prince Pavlos of Greece), rationing water, eating freeze-dried astronaut food, and living in a stripped-clean hull with nothing to weigh it down. Miller is proud of his current dominance in racing, and he’d like to see if he can break the monohull record for sailing around the world, which stands at 93 days. He expects Mari-Cha IV to continue winning for at least another year, by which time someone will have managed to build a faster boat. “I’ll be very unhappy,” says Miller, knowing that when that happens he’ll be back at the drawing board.

‘I’m on the world’s most luxurious sailing yacht, and I have to live up to it,” says Mouna Ayoub as the moon rises over Cap-Ferrat and her stewards serve us a six-course extravaganza of nouvelle-French fish dishes on the everyday Christofle by Bernardaud china—not the 150-year-old Meissen, which is reserved for royalty. Our hostess is wearing white fox, a Galliano gown, and big diamonds, and we are on Phocea, her magnificently restored four-masted schooner, which has a 16-member crew and sycamore interiors by Viscount David Linley, nephew of the Queen. Having divorced one of the world’s richest men, the extravagant couture buyer oversees every aspect of her yacht, which she charters out for 197,000 euros a week.

She calls her acquisition of the boat “a love story about a woman who was deprived of freedom since she was five, a love story about a woman who found love and freedom. It’s not a man who gave me this. It’s Phocea. ” She spotted Phocea in the Bay of Volpe, off Sardinia, in 1992 and fell in love with it. Back then she was ensconced on Lady Moura, now the seventh-largest yacht in the world, the 344-foot possession of Saudi Arabian Dr. Nasser al-Rashid, which, when it was launched in 1991 at an estimated cost of $100 million, was the most expensive yacht ever built. Ayoub had designed the interiors, “the whole boat, every inch,” and its name was an acronym of her name and Rashid’s. The couple divorced in 1996.

World-class clotheshorse Mouna Ayoub on Phocea , which she bought in a dilapidated state for $5.35 million and restored at a cost of $30 million.

In her memoir, La Vérité, she wrote that her life as the wife of a Middle Eastern magnate was a prison from which she could escape only in an abaya and veils, but tonight she refuses to discuss her ex-husband or his boat. She recalls the morning in 1992 when she left Lady Moura on a tender for a jog along the Bay of Volpe and first saw Phocea. She swam up to it and asked for a tour. Her request was denied because the owner, entrepreneur Bernard Tapie, who owns the Olympic Marseille football club, was asleep.

Back on Lady Moura, Ayoub stood on the A Deck and gazed at Phocea. “I knew that with those sails I could go anywhere, even without an engine,” she says. She made a vow: “One day she’s going to be mine, and nobody is going to prevent me from coming on board.” Even before her divorce, she went after Phocea, and after its owner was convicted of bribery, the yacht ended up, she has written, “sad and neglected, in Port Vauban, where she lingered for months begging for love and care. I decided that I should be the one to save her.” Though the chief engineer of Lady Moura told her Phocea was a wreck, Ayoub bought it at auction for $5.35 million and launched a $30 million restoration.

Yachtsmen speak about porn boats, yachts with all-female crews, and yachts with stripper poles and endless lines of “trolley dollies,” those loose young women forever eager to roll their suitcases down gangplanks. But the template for misbehavior at sea is docked in Monte Carlo’s Port of Font-vieille, the low-slung, two-masted schooner called Zaca, the infamous yacht of the late actor Errol Flynn, who, the six-member crew insists, still haunts the boat on which he slowly went insane, despite an actual exorcism by the Anglican Archdeacon of Monaco in 1978.

“We feel him here; things happen that we just can’t explain,” says the captain, Bruno dal Paz, leading me into *Zaca’*s saloon, which has been restored by an Italian businessman and hung with a 1943 Picasso. Captain Bruno opens a thick scrapbook of yellowed press clippings. In 1946, Flynn, after beating the charge that he had committed statutory rape on his first yacht, Sirocco, fled Hollywood. “Instead of killing myself I bought a new boat,” he wrote in his autobiography, My Wicked Wicked Ways. Perhaps Zaca, Samoan for “peace,” was cursed from the start; at its 1930 christening, the champagne bottle failed to break on its bow, always a bad omen. On one of Flynn’s first voyages, Zaca sank. On another, his crew mutinied. On what was supposed to be a “make-up” cruise, Orson Welles split from his wife, Rita Hayworth. After two wives left Flynn, the swashbuckler fell into a delirium of booze and drugs on the boat—a descent that included orgies, drug smuggling, a trip to Mexico to help a friend who was a Nazi evade an arrest warrant, and a second rape charge, by a woman barely of legal age. At 50, Flynn was “drinking vodka for breakfast and keeping a condom full of cocaine in his swim trunks,” according to a clipping in *Zaca’*s scrapbook. “I’ve squandered seven million dollars. I’m going to have to sell Zaca, ” Flynn lamented in an interview just before flying to Vancouver with his 17-year-old girlfriend, Beverly Aadland, to sell it for $150,000. The sale never took place, however, because Flynn had a heart attack, or committed suicide, just before signing the papers.

There are approximately 30,000 people working on yachts. Moving from one giant vessel to another, I was amazed at how young, attractive, well educated, and multi-lingual the crews all were. I soon discovered that, for every crew member employed, there are hundreds waiting to join a career that comes with unlimited perks (I watched the crew of Skat eating rack of lamb and drinking Taittinger for dinner) and excellent pay (a captain’s annual salary is $1,000 per yacht foot, and crews are usually paid in cash, says Dallas-based international financial consultant George Kline, who invests many a captain’s and crew member’s earnings). Even off duty, they refuse to mention specific owners or yachts, because they generally sign confidentiality agreements with their employers.

“On a boat I’m not going to mention, we had a group of Americans out for the Cannes Film Festival,” says Sebastian Frazer, a steward. “One night they went into the Jacuzzi with five women, but then the men went to bed, leaving the women, who began a full-on porn show. By then we’d lifted anchor from the Bay of Cannes, and they were going at it, completely oblivious that there were boats on both sides. The funny thing was that the Jacuzzi wouldn’t get hot enough, so we were boiling water and running up three levels with kettles to warm it, while also serving them Dom Pérignon. Even though the women hadn’t chartered the yacht, any guest that comes on board you still treat as a paying guest.”

In the mid-90s, a yacht owner placed one of the first ads to offer charters in a Moscow newspaper, and newly rich Russians swarmed to pony up $250,000 for a week on the boat. “ Whiskey beer! ” was all the first Russian on board said, at eight in the morning. “I took a step back, and he repeated it three times. Bring whiskey beer!’” remembers a steward named Gabriel, who arranged multiple brands of whiskey and beer on a silver tray, which he presented to the guest, who immediately began slugging down a succession of boilermakers. Soon a party was raging. “Six guys, 15 prostitutes—behavior that would send shivers down your spine,” says the steward. “Every horizontal surface on the boat gets some action. When the crew’s around, they generally give us a wink ... and keep going.”