- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

Backstays to the Future

- By Alvah Simon

- Updated: March 28, 2013

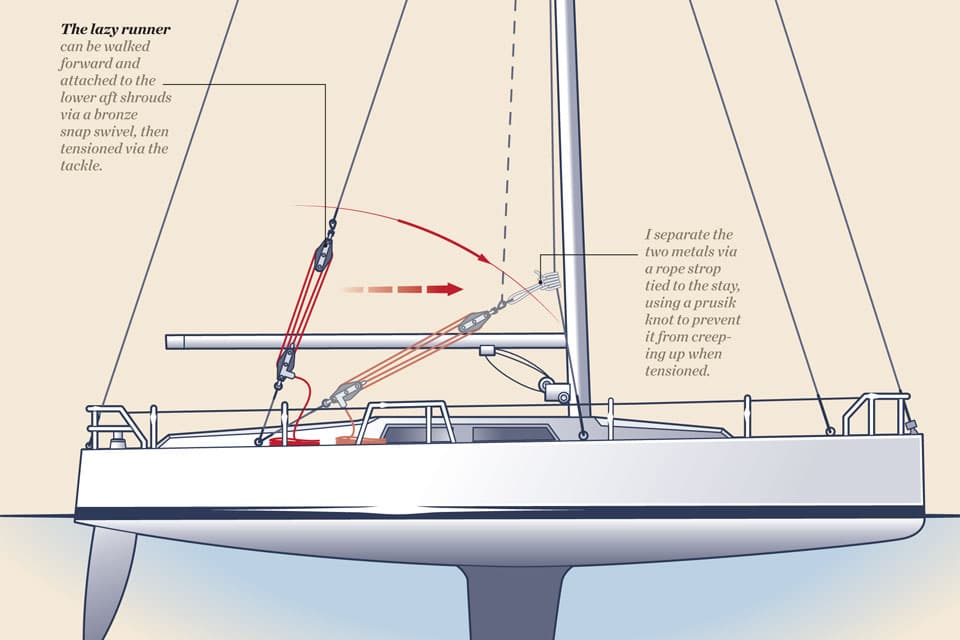

backstay setup

A running backstay is a removable stay that provides aft support to the mast from either the masthead or the point at which an inner forestay is attached. It originated as a response to the material limits of the period. At that time, solid wooden masts, for example, were either too weak or too heavy to be made particularly tall. Therefore, to achieve an acceptable area of sail for the heavy-displacement boats of the day, either the boom had to be extended beyond the transom or a gaff had to be added to the top of the sail—or both. This precluded the use of fixed backstays because the boom and gaffs had to be free to swing across the vessel when it tacked and jibed. As a tack or jibe was initiated, the burdened backstay had to be released and, as the spars swung through, the new, now windward, stay had to be fastened quickly before the entire rig came tumbling down.

With the advent of hollow masts, first of wood and then of alloy, and stainless-steel wire, the aspect ratio of the rigs began to extend to 3-to-1 and beyond. This allowed for the development of the Bermuda or Marconi rig, which eliminated gaffs and shortened the booms considerably without the loss of sail area or performance.

Running backstays, or runners, were then generally found only on cutter-rigged vessels. But through the 1960s and 1970s, the sloop became the rig du jour, and running backstays fell from favor. With the introduction of Freedom Yachts’ freestanding mast and Hunter’s B&R rig, the trend veered toward eliminating backstays, running or not, altogether.

Where are we today? Are running backstays now simply anachronisms that add unnecessary weight, windage, and clutter? I think not, especially in the context of bluewater cruising.

Sloops are fast around the buoys, but in the open sea, they display two disadvantages. First, the sail area is shared by only two large and therefore more difficult to handle sails. Second, in storm conditions, a sloop’s headsail, no matter how much it’s furled, still leaves the center of effort too far forward and too high to produce a safe and comfortable motion.

The cutter rig distributes the sail area over an additional sail, and that inner forestay is a superior position from which to hank on a low-flown storm sail. But with any real force upon it, the inner forestay can distort the shape of the mast; this will require a countereffort. Enter the intermediate running backstay. The arguable benefit of a staysail aside, this lower triangulation of support adds strength and stability to the mast, which translates into a better chance of coming up from a knockdown with the rig intact. Think sailing in the South Atlantic Ocean —it matters.

But alas, when you’re sailing off the wind, these same runners will have to be attended to on each and every tack. In open-ocean situations, this might not happen for days at a time. In confined waters, however, it’s necessary to have a quick and efficient method for setting and stowing runners.

Ideas and hardened opinions on running backstays are diverse and plentiful enough to keep seaside barstools warm all night. See the accompanying images and diagrams to learn about some of the most common approaches to setup and stowage.

If you’re considering adding an inner forestay and running backstays, I recommend that you get professional advice addressing the minimum engineering angles required, appropriate deck hardware, proper tangs and toggles needed at the mast, and wire types and diameters.

I don’t mean to imply that running backstays are suitable for all boats and applications. But if your interests lie in bluewater passagemaking and you take a belt-and-suspenders approach to your safety, I believe that you’ll agree that the added weight, windage, cost, and inconvenience are more than justified.

Alvah Simon, a CW contributing editor, is the author of North to the Night .

Click here for more pictures of running backstay setups . Click here to read about how an inner forestay and staysail can help you beat along in a blow.

- More: How To , seamanship , ship's systems

- More How To

Preparing to Head Out

Adding Onboard Electronics? Here’s How To Get Started

7 Boating Safety Tips for Summer Cruising

How to Prep for a Diesel You Can Depend On

Sailboat Review: Italia Yachts 14.98

Competitive Cruising: It’s a Rally, Not a Race

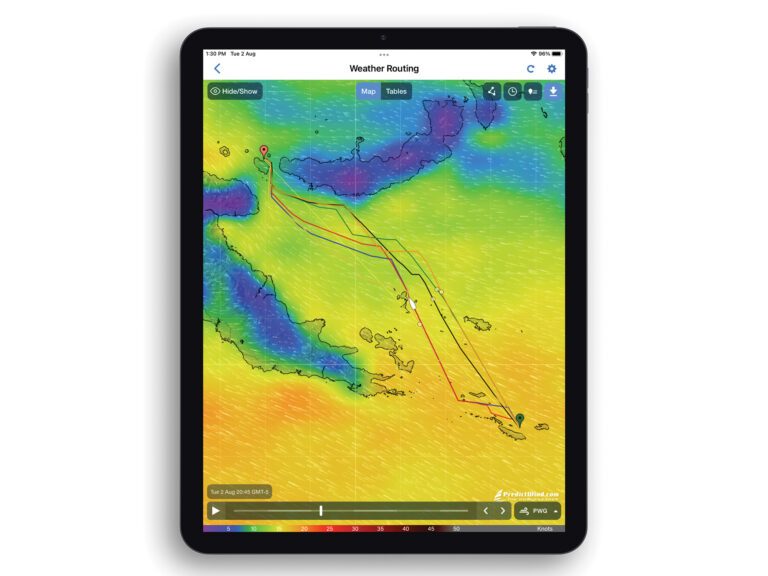

The Data Difference: Advances in Marine Weather Forecasting

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Standing Rigging (or ‘Name That Stay’)

Published by rigworks on november 19, 2019.

Question: When your riggers talk about standing rigging, they often use terms I don’t recognize. Can you break it down for me?

From the Rigger: Let’s play ‘Name that Stay’…

Forestay (1 or HS) – The forestay, or headstay, connects the mast to the front (bow) of the boat and keeps your mast from falling aft.

- Your forestay can be full length (masthead to deck) or fractional (1/8 to 1/4 from the top of the mast to the deck).

- Inner forestays, including staysail stays, solent stays and baby stays, connect to the mast below the main forestay and to the deck aft of the main forestay. Inner forestays allow you to hoist small inner headsails and/or provide additional stability to your rig.

Backstay (2 or BS) – The backstay runs from the mast to the back of the boat (transom) and is often adjustable to control forestay tension and the shape of the sails.

- A backstay can be either continuous (direct from mast to transom) or it may split in the lower section (7) with “legs” that ‘V’ out to the edges of the transom.

- Backstays often have hydraulic or manual tensioners built into them to increase forestay tension and bend the mast, which flattens your mainsail.

- Running backstays can be removable, adjustable, and provide additional support and tuning usually on fractional rigs. They run to the outer edges of the transom and are adjusted with each tack. The windward running back is in tension and the leeward is eased so as not to interfere with the boom and sails.

- Checkstays, useful on fractional rigs with bendy masts, are attached well below the backstay and provide aft tension to the mid panels of the mast to reduce mast bend and provide stabilization to reduce the mast from pumping.

Shrouds – Shrouds support the mast from side to side. Shrouds are either continuous or discontinuous .

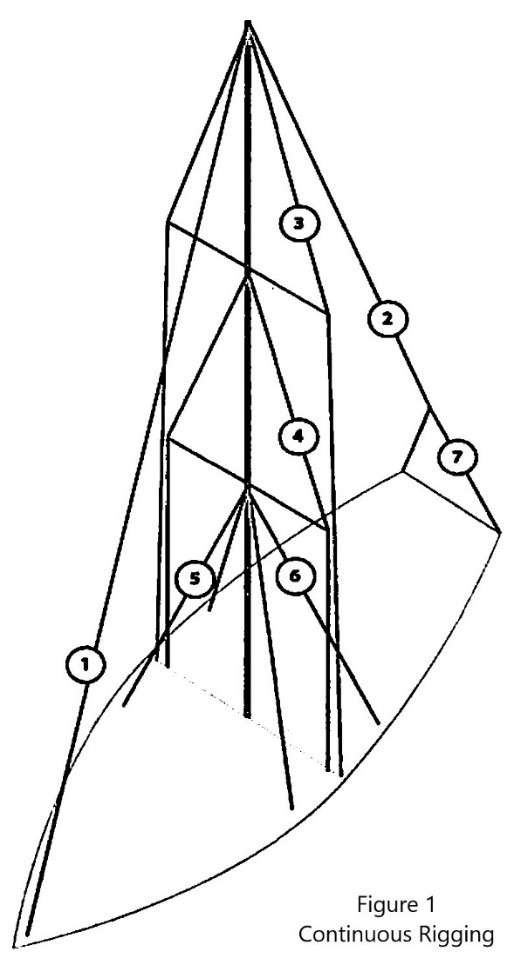

Continuous rigging, common in production sailboats, means that each shroud (except the lowers) is a continuous piece of material that connects to the mast at some point, passes through the spreaders without terminating, and continues to the deck. There may be a number of continuous shrouds on your boat ( see Figure 1 ).

- Cap shrouds (3) , sometimes called uppers, extend from masthead to the chainplates at the deck.

- Intermediate shrouds (4) extend from mid-mast panel to deck.

- Lower shrouds extend from below the spreader-base to the chainplates. Fore- (5) and Aft-Lowers (6) connect to the deck either forward or aft of the cap shroud.

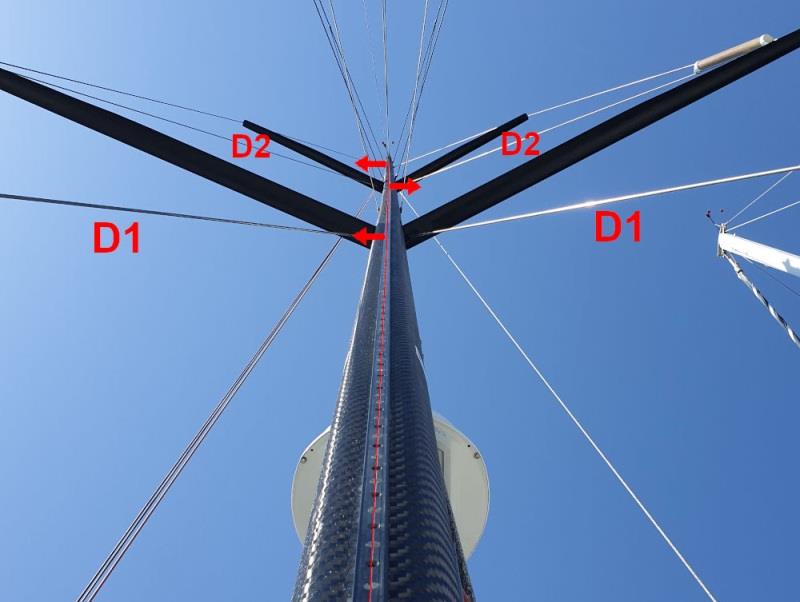

Discontinuous rigging, common on high performance sailboats, is a series of shorter lengths that terminate in tip cups at each spreader. The diameter of the wire/rod can be reduced in the upper sections where loads are lighter, reducing overall weight. These independent sections are referred to as V# and D# ( see Figure 2 ). For example, V1 is the lowest vertical shroud that extends from the deck to the outer tip of the first spreader. D1 is the lowest diagonal shroud that extends from the deck to the mast at the base of the first spreader. The highest section that extends from the upper spreader to the mast head may be labeled either V# or D#.

A sailboat’s standing rigging is generally built from wire rope, rod, or occasionally a super-strong synthetic fibered rope such as Dyneema ® , carbon fiber, kevlar or PBO.

- 1×19 316 grade stainless steel Wire Rope (1 group of 19 wires, very stiff with low stretch) is standard on most sailboats. Wire rope is sized/priced by its diameter which varies from boat to boat, 3/16” through 1/2″ being the most common range.

- 1×19 Compact Strand or Dyform wire, a more expensive alternative, is used to increase strength, reduce stretch, and minimize diameter on high performance boats such as catamarans. It is also the best alternative when replacing rod with wire.

- Rod rigging offers lower stretch, longer life expectancy, and higher breaking strength than wire. Unlike wire rope, rod is defined by its breaking strength, usually ranging from -10 to -40 (approx. 10k to 40k breaking strength), rather than diameter. So, for example, we refer to 7/16” wire (diameter) vs. -10 Rod (breaking strength).

- Composite Rigging is a popular option for racing boats. It offers comparable breaking strengths to wire and rod with a significant reduction in weight and often lower stretch.

Are your eyes crossing yet? This is probably enough for now, but stay tuned for our next ‘Ask the Rigger’. We will continue this discussion with some of the fittings/connections/hardware associated with your standing rigging.

Related Posts

Ask the Rigger

Do your masthead sheaves need replacing.

Question: My halyard is binding. What’s up? From the Rigger: Most boat owners do not climb their masts regularly, but our riggers spend a lot of time up there. And they often find badly damaged Read more…

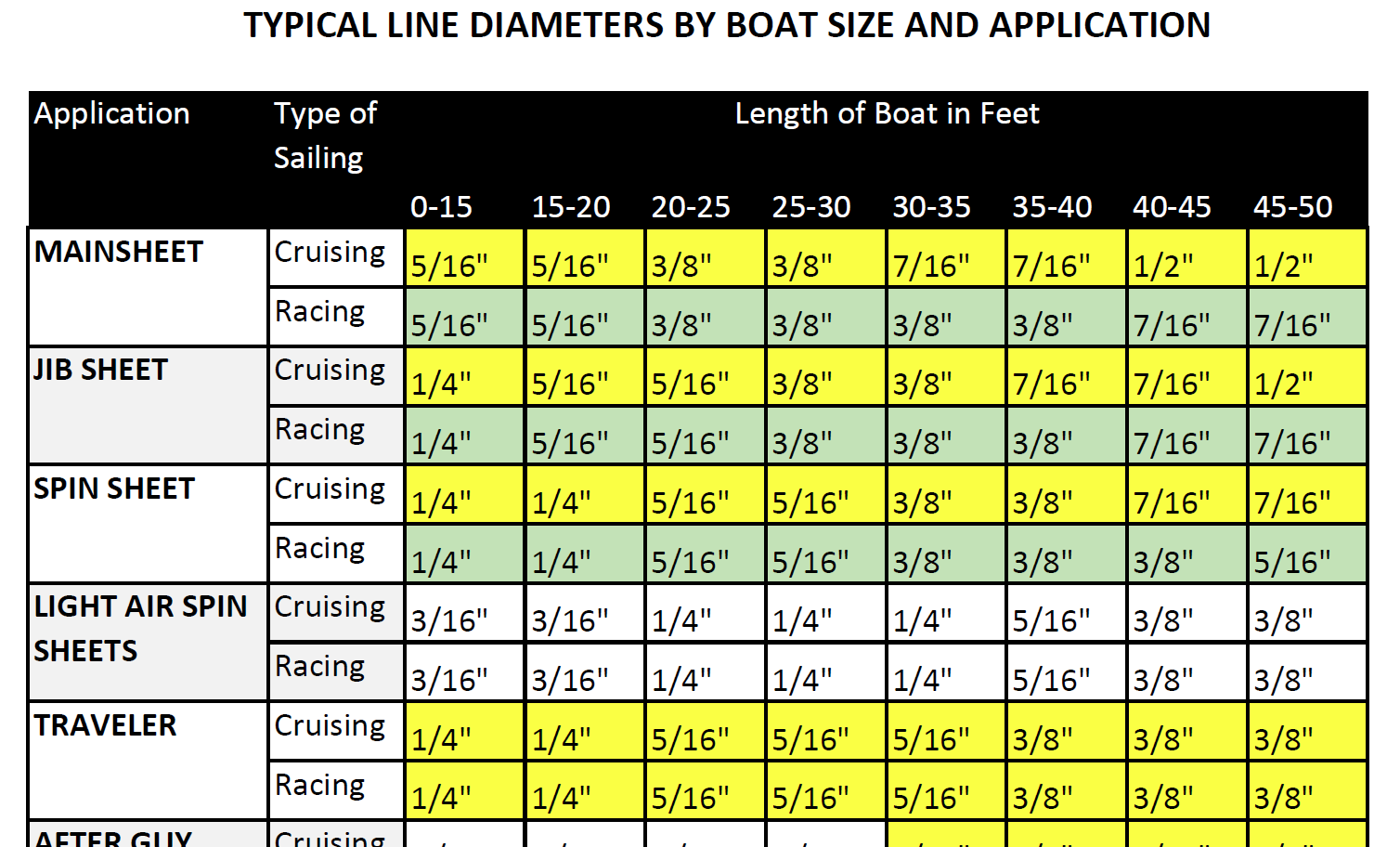

Selecting Rope – Length, Diameter, Type

Question: Do you have guidelines for selecting halyards, sheets, etc. for my sailboat? From the Rigger: First, if your old rope served its purpose but needs replacing, we recommend duplicating it as closely as possible Read more…

Spinlock Deckvest Maintenance

Question: What can I do to ensure that my Spinlock Deckvest is well-maintained and ready for the upcoming season? From the Rigger: We are so glad you asked! Deckvests need to be maintained so that Read more…

The $tingy Sailor

Diy trailerable sailboat restoration and improvement without throwing your budget overboard.

Upgrade Your Rig With a DIY Adjustable Backstay

At some point when you get serious about sail trim, whether for racing or just high performance cruising, you’re going to want an adjustable backstay. Most C-22s and similar daysailers were rigged at the factory with fixed length backstays that are only slightly adjustable with a turnbuckle. They’re not intended for adjusting to different wind conditions. You set it and forget it.

Consequently, you only have one setting for mast bend and headstay tension. That’s fine for casual cruising. Set it for the conditions that you usually sail in and it will usually be close. But an adjustable backstay gives you a range of trim positions to optimize the mainsail and headsail shape for any conditions, which are what you can encounter when racing or when you’re no longer just a fair weather skipper.

Before I continue, a bit of legal housekeeping. This post contains affiliate links. That means I receive a small commission if you make a purchase using those links. Those commissions help to pay the costs associated with running this site so that it stays free for everyone to enjoy. For a complete explanation of why I’m telling you this and how you can support this blog without paying more, please read my full disclosure .

In other rigging posts on this site, I’ve described how to add DIY controls for each of the three sides of a mainsail:

- Luff – Control Mainsail Draft with a Boom Downhaul

- Leech – Control Your Mainsail Shape Better With a Boom Vang

- Foot – Flatten Your Mainsail Foot with an Outhaul

Each of them secondarily affects the middle or belly of the mainsail a little bit but an adjustable backstay primarily affects it and completes the sail trim picture. Genoa car placement also affects the leech and foot of the headsail and halyard tension also affects the luff. An adjustable backstay primarily affects the belly of the headsail. The cool thing about an adjustable backstay is that it affects the belly of both sails at the same time. It’s a two-for-one control that improves performance both upwind and downwind.

How an adjustable backstay improves sail shape

Your mainsail might have been designed and built with a slight outward curve in the luff specifically to take advantage of bend in your mast. With a fixed backstay or a loosened adjustable backstay, the mast (and consequently, the luff) is relatively straight. This lets the mainsail form a more rounded shape in its belly when it’s filled with air, which adds power and is just what you want in light air. The extra fabric width in the middle of the sail has to go somewhere, so it fills to leeward.

When you tighten an adjustable backstay, the top of the mast curves slightly aft. This makes it fit the curve in the mainsail luff, which flattens and depowers the mainsail, just what you want in a strong breeze. Even if your mainsail has a straight luff, the effect is the same. The mainsail is more efficient and the boat will heel less. Hence, you might not need to reef the mainsail as early or at all.

Similarly, your headsail was probably designed and built with straight luff but it can take advantage of an adjustable backstay as well. With a fixed backstay or a loosened adjustable backstay, the forestay should be tuned with several inches of sag in it. Like the mainsail, this lets the headsail form a more rounded shape in its belly when it’s filled with air, again, just what you want in light air.

When you tighten an adjustable backstay, since it pulls the masthead slightly aft, it also increases the tension on the headstay and pulls the sag out. Then it is straight and matches the luff, which removes some of the belly of the headsail and flattens it, again, just what you want in a strong breeze. Together with the mainsail, it too becomes more efficient.

Incidentally, a tighter headstay can also make your headsail furler work better. An adjustable backstay can also make trailering easier without the need for a quick release lever on the forestay. It lets you slacken the forestay, which can make disconnecting it to unstep the mast easier, especially if you have a furler. If you need just a little more slack, pull the mast forward by hand with one of the halyards.

The simple animation below illustrates this simultaneous flattening of the mainsail and headsail. An adjustable backstay deepens the middle of both sails a few inches.

Another benefit of an adjustable backstay is that after a day of sailing with a tight backstay in a strong breeze, you can slacken the backstay to let the rig relax and release tension on the hull while your sailboat is moored.

Direct vs. indirect backstays

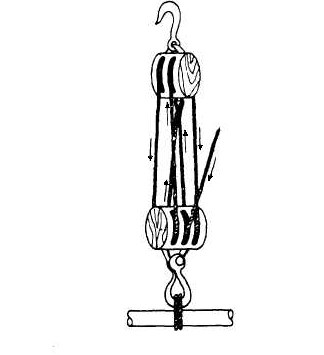

Adjustable backstay designs fall into two types: direct and indirect. With a direct adjustable backstay, the adjuster (typically a tackle system) is integrated into the backstay. The adjuster directly controls the length of the backstay and bears the full load of the backstay. This is the type of system that I’ll describe how to make in this post.

The advantages of a direct system are that it is simpler and therefore, more economical to make. It’s also more mechanically efficient compared to indirect systems, as I’ll explain in a moment. The disadvantage of a direct system is that if any part of the adjuster breaks, the entire backstay can fail. That’s not likely to happen except under extreme conditions and it can be safeguarded against by adding a safety wire or strap to back up the adjuster in case of failure.

With an indirect adjustable backstay, the adjuster (also typically a tackle system) is not integrated into the backstay and it doesn’t carry the full load of the backstay. The adjuster indirectly controls the length of the backstay, which can function without the adjuster. The advantage of an indirect system is that it is more fail-safe. If the adjuster breaks, the backstay can continue to work, albeit without adjustment ability. The disadvantage of an indirect system is that is more complicated and therefore, more expensive to make and to maintain.

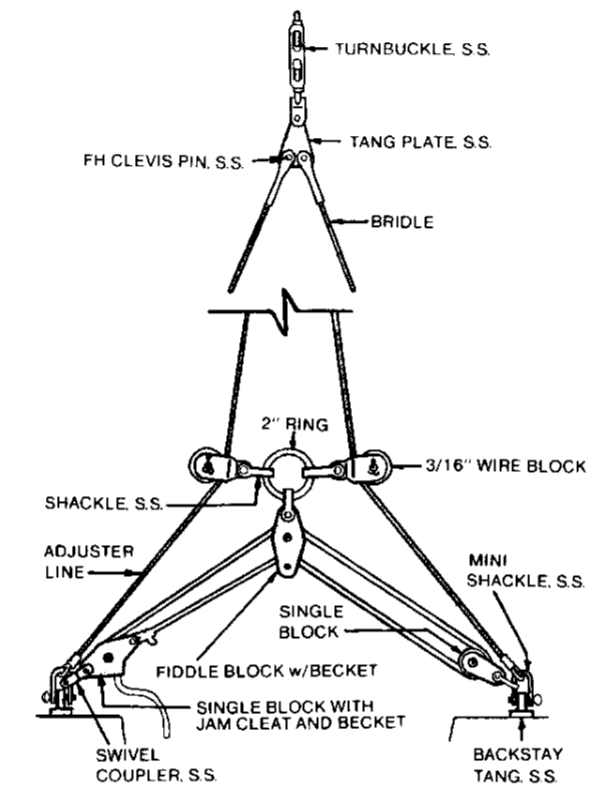

The adjustable backstay that was installed on C-22s at the factory is an indirect system that looks like this;

Tightening the tackle system pulls the center ring down, which pulls the bridle wires together and shortens the overall length of the backstay. Another disadvantage of this design is that the more you tighten the tackle, its mechanical advantage decreases.

The angle of the line through the center fiddle block decreases and the angle of the bridle wires through the wire blocks increases. Both of these effects increase the amount of force required to shorten the backstay. The end result is, it’s easier to adjust at the beginning of the adjustment range and harder to adjust at the end of the adjustment range. It gets hardest in strong winds, right when you need it most. That is why most modern backstays are direct designs.

DIY materials list

Following are the parts and materials you’ll need to make the direct adjustable backstay shown. I used a 5:1 tackle system because that’s what I had on hand but you could substitute a 4:1 tackle (two double blocks, no triple block) instead. It’s important that the breaking load of each part is equal to or greater than the breaking load of the backstay wire. You don’t want the adjuster to be the weakest link.

- Harken #304 1-1/2″ wire block or equivalent

- Harken #94 29mm triple block with cam cleat or equivalent

- Harken #85 29mm double block with becket or equivalent

- 1/2″ x 13 tpi SS eye bolt. The older C-22s used nearly identical eye bolts for the backstay, keel cable attachment, and the chain plate bolts. They’re readily available and inexpensive on eBay. However, the chain plate bolts are not threaded the full length of the bolt to the flange and need spacing washers. The backstay and keel eye bolts are fully threaded, do not need spacing washers, and are preferred for this project.

- 1/2″ SS washers (4-6 required if the eye bolt is not fully threaded)

- 20′ x 1/4″ New England Ropes Sta Set double braid

- 22′ x 1/8″ 1×19 SS wire w/swaged eyes on both ends. This is the main, non-adjustable part of the backstay.

- 10′ x 1/8″ 7×7 SS wire w/swaged eyes on both ends. This is the adjustable part of the backstay. Do NOT use 1×19 wire for this piece, which is not designed for use with wire blocks.

- SS shackles to attach the backstay to the eye bolts

For tips to help you decide whether to make the wire parts of the backstay yourself or to have a rigger make them for you, see How to Replace Your Standing Rigging for Less .

Installation instructions

To assemble and install the direct adjustable backstay shown:

1. If your sailboat already has an eye bolt installed in the port side of the transom, skip to step 2. If your sailboat does NOT have an eye bolt already installed in the port side of the transom, continue with this step. If your sailboat is not a Catalina 22, modify these instructions to provide adequate transom reinforcement.

A. Drill a 1/8″ starter hole through the top of the transom 2″ outboard of the traveler bar (6″ from the port side of the tiller cutout). Place the hole in the middle of the transom thickness. There is a 5/16″ thick brass bar embedded by the factory in the top of the transom for this purpose. Drill completely through the bar.

B. Redrill the hole to enlarge it to 3/8″ or 27/64″ (preferable if you have that bit).

C. Chamfer the fiberglass down to the brass bar with a countersink bit or large drill bit.

D. Tap the hole to 1/2″ x 13 tpi. The finished hole should look like this:

2. Test fit the 1/2″ eye bolt in the hole to decide how many washers you need for a tight fit. The tab of the eye bolt when tightened must point toward the cockpit like the picture below.

3. Apply a 1/4″ cone of butyl tape around the bolt and the underside of the lowest washer so that it will fill the countersink in the transom and squeeze out a little.

4. Apply blue thread locker to the eye bolt threads and install the eye bolt snug.

Do not overtighten the bolt or you might strip the brass threads. If you do strip the threads, then you will need to drill the hole out to 1/2″ and add washers and nuts on the inside of the transom, which is very difficult just to see, let alone work on. This is also a possible workaround if your sailboat is not a C-22. In that case, most owners end up cutting access holes in the front of the transom to install the nuts and then cover the holes with access plates or vents. To make matters worse, the back of the transom has a wood core and is thicker, the front of the transom has no core and is thinner. With the eye bolt centered on the transom, the threaded end of the bolt barely clears the core inside the transom. You will have to cut into the core to create clearance for the washers and nuts. To avoid all this, don’t strip the eye bolt threads.

5. Unstep the mast and, if necessary, move it so that you can work on the masthead.

6. Remove the existing backstay and attach one end of the 22′ wire to the masthead in its place.

7. Step the mast and reconnect the shrouds.

8. Reave the 10′ wire through the wire block and attach the wire block to the loose end of the 22′ wire like this:

9. Use a shackle to connect one end of the 10′ wire to the transom eye bolt on the opposite side (typically the starboard side) from where you want the adjuster cam cleat to be located (typically the port side).

10. Attach the double block with becket to the loose end of the 10′ wire like this:

11. Reave the 1/4″ double braid line through the double and triple blocks.

Use a double luff reaving order like shown below.

Start from the becket on the double block, reave the line through the sheaves on one side of both blocks, through the opposite sides of both blocks in the opposite direction, and exit through the middle sheave of the triple block and the cam cleat. Do not spiral reave the line through the sheaves. Leave a long tail in the line until after the backstay is installed and the rig tuned.

12. Use a shackle to connect the triple block to the remaining eye bolt (typically on the port side) like this:

The completed installation should look like this:

13. With the adjuster slack, check the mast rake and prebend and the standing rigging tuning. If you’re not sure how, refer to the Catalina 22 Tuning Guide from North Sails. If you don’t have a tension gauge, consider purchasing one after you read How To Measure Standing Rigging Tension .

14. Tighten the adjuster just enough to take the slack out of the backstay and so that it won’t interfere with the boom when the mainsail is raised. This will be the minimum backstay tension setting.

15. Tie a stopper knot in front of the cam cleat to prevent the adjuster from being slackened any further.

16. Trim the excess adjuster line to leave about a 1′ tail. Tie another stopper knot on the end to give a better grip on the line.

17. Tighten the adjuster to 25% of the breaking strength of the main wire or the bridle wire, whichever is less . This should bend the top half of the mast aft a few inches. This will be the maximum backstay tension setting that you should not exceed.

For example, if the breaking load of the main wire is 1587 lbs and the breaking load of the bridle wire is 1350 lbs, calculate 25% of 1350 lbs, which is 337.5 lbs or a setting of 25 on a Loos PT1 tension gauge.

18. Mark the adjuster line in front of the cam cleat with a permanent marker. Do not tighten the adjuster beyond this mark when you are sailing.

Now go out and practice adjusting your new backstay in various wind conditions to optimize the headsail and mainsail shape and maximize your pointing ability and speed. When you’re done for the day, slacken the adjuster to the minimum setting.

Would you like to be notified when I publish more posts like this? Enter your email address below to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. You will also receive occasional newsletters with exclusive info and deals only for subscribers and the password to the Downloads page. It’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time but almost nobody does!

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Share this:

11 thoughts on “ upgrade your rig with a diy adjustable backstay ”.

Nice description of the why and how to add the direct backstay adjuster. If one doesn’t have a transom with the brass structure to mount to, I assume one would want to use the typical metal backplate when installing that eyebolt? Cheers, and thanks for some fresh inspiration to work on my project boat!

Yep, treat it just like you would a chain plate bolt because it’s doing much the same job.

I had an indirect system when I got my boat and it functioned (minimally) as you describe. I couldn’t tell any difference. Then I installed a system as you outline here. sailing on a close reach in light air and flat water, I could actually FEEL the boat accelerate as I eased the backstay and I could FEEL the boat slow down as the sails stalled when I tightened it up. I played with it for half hour like this just appreciating the noticeable difference from the “indirect” method I had previously uses. This is one of the best modifications you can make to your boat.

Thanks for sharing your experience, Mike!

Did your adjustable backstay make your quick release on the forestay and shrouds redundant?

Hello, Harry

No, I still use the levers with the adjustable backstay, especially on the forward lower shrouds. But I also tune my standing rigging a little tighter than normal for racing. I might be able to pin/unpin the forestay without a lever and the backstay relaxed but it wouldn’t be quick or easy.

Thanks for asking, $tingy

Hello, I have a few questions regarding adjustable backstay for C22. I am planing to replace rigging on my currently acquired Catalina 22 sport. Since I already have eye bolt installed in the port side, I think it would be good idea to install adjustable backstay, for two reasons: adjustment of back stay and better tension distribution (two bolts vs 1 bold). The only concern I have is safety, as you mentioned in your article (“The disadvantage of a direct system is that if any part of the adjuster breaks, the entire backstay can fail.”). So, is there risk that whole mast can fall or can aft shourds still hold the mast up? What is your recommendation for wire or strap to back up the adjuster in case of failure? Thank you.

I haven’t read any stories of adjustable backstays failing but that doesn’t mean there aren’t any, I just haven’t dug deep enough. My guess would be that a backstay failure would result in the mast folding forward above the lower shroud tangs. Assuming the standing rigging was in good condition otherwise, it would take a lot of wind to cause to cause it to fail and it would probably fail at a block or terminal. Sudden failure of the backstay would allow all of the load on the foresail to pull the top of the mast forward impeded only by the mainsail leech, main sheet, and possibly a vang. The upper and lower shrouds would likely survive and hold the bottom half of the mast in place. All this is speculation, of course, and the actual conditions would determine the result.

That said, I don’t have a safety strap on my adjustable backstay even though I do race my C-22 and occasionally sail in winds that can completely overpower it. But if I were to add one, I’d add a short length of wire rope on the static side of the adjuster with one end attached below the bridle block and the other end attached above the bridle block. I’d make it with no slack when the adjuster is at minimum tension. As the adjuster is tightened, the safety strap will slacken slightly and have the most slack when the backstay is at its tightest. Its purpose would not be to maintain tension on the backstay in case of a failure but simply to limit the masthead from springing forward and bending catastrophically. I wouldn’t use nylon webbing, which can deteriorate from UV exposure.

Hope that helps. Send me a picture of your sailboat if you would like to add it to the Readers Gallery. There aren’t any C-22 Sports there yet. $tingy

I purchased a Catalina Capri 26 about a year ago and have been thinking about upgrading to an adjustable backstay, that’s how I found your article and site which is very helpful. The current (non-adjustable) backstay runs diagonally from the masthead to a chainplate mounted to the transom (exterior – port side) about 18″ above the waterline. I was thinking of adding another chainplate same in the same area on the starboard side. But in order to have the adjusting sheet accessible to the cockpit I would need to reverse the configuration by attaching the Harken double block with becket down below at the chainplate and the Harken triple block with cam-cleat above near the skipper. Is that feasible and something that will work? I look forward to any advice you can offer and of course all your future articles!

Thanks, Kirk

I understand what you want to do but inverting the cam cleat block wouldn’t be very safe. The line tail would hang down and if a crew member or a fouled line accidentally pulled it downward, it could uncleat and unexpectedly slacken the backstay, which could damage the mast. Instead, consider leaving the tackle in the upright position and raise the whole assembly up with a short pendant or a long tang to where the skipper can reach it. Be sure every component in the system is rated to a working load at least equal to the backstay wire. However, I couldn’t find where anybody has done this before so you might be in uncharted territory and therefore I must recommend against it.

I do appreciate you getting back to me I had the same thought about a short pendant. I totally understand why you can’t (legally) endorse that but think I’m going to take a shot at it and make it as bullet proof as possible. Once again, thank you for your articles and I’m looking forward to several projects this winter as I really look forward to next Spring!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

The Standing Rigging On A Sailboat Explained

The standing rigging on a sailboat is a system of stainless steel wires that holds the mast upright and supports the spars.

In this guide, I’ll explain the basics of a sailboat’s hardware and rigging, how it works, and why it is a fundamental and vital part of the vessel. We’ll look at the different parts of the rig, where they are located, and their function.

We will also peek at a couple of different types of rigs and their variations to determine their differences. In the end, I will explain some additional terms and answer some practical questions I often get asked.

But first off, it is essential to understand what standing rigging is and its purpose on a sailboat.

The purpose of the standing rigging

Like I said in the beginning, the standing rigging on a sailboat is a system of stainless steel wires that holds the mast upright and supports the spars. When sailing, the rig helps transfer wind forces from the sails to the boat’s structure. This is critical for maintaining the stability and performance of the vessel.

The rig can also consist of other materials, such as synthetic lines or steel rods, yet its purpose is the same. But more on that later.

Since the rig supports the mast, you’ll need to ensure that it is always in appropriate condition before taking your boat out to sea. Let me give you an example from a recent experience.

Dismasting horrors

I had a company inspect the entire rig on my sailboat while preparing for an Atlantic crossing. The rigger didn’t find any issues, but I decided to replace the rig anyway because of its unknown age. I wanted to do the job myself so I could learn how it is done correctly.

Not long after, we left Gibraltar and sailed through rough weather for eight days before arriving in Las Palmas. We were safe and sound and didn’t experience any issues. Unfortunately, several other boats arriving before us had suffered rig failures. They lost their masts and sails—a sorrowful sight but also a reminder of how vital the rigging is on a sailboat.

The most common types of rigging on a sailboat

The most commonly used rig type on modern sailing boats is the fore-and-aft Bermuda Sloop rig with one mast and just one headsail. Closely follows the Cutter rig and the Ketch rig. They all have a relatively simple rigging layout. Still, there are several variations and differences in how they are set up.

A sloop has a single mast, and the Ketch has one main mast and an additional shorter mizzen mast further aft. A Cutter rig is similar to the Bermuda Sloop with an additional cutter forestay, allowing it to fly two overlapping headsails.

You can learn more about the differences and the different types of sails they use in this guide. For now, we’ll focus on the Bermuda rig.

The difference between standing rigging and running rigging

Sometimes things can get confusing as some of our nautical terms are used for multiple items depending on the context. Let me clarify just briefly:

The rig or rigging on a sailboat is a common term for two parts:

- The standing rigging consists of wires supporting the mast on a sailboat and reinforcing the spars from the force of the sails when sailing.

- The running rigging consists of the halyards, sheets, and lines we use to hoist, lower, operate, and control the sails on a sailboat.

Check out my guide on running rigging here !

The difference between a fractional and a masthead rig

A Bermuda rig is split into two groups. The Masthead rig and the Fractional rig.

The Masthead rig has a forestay running from the bow to the top of the mast, and the spreaders point 90 degrees to the sides. A boat with a masthead rig typically carries a bigger overlapping headsail ( Genoa) and a smaller mainsail. Very typical on the Sloop, Ketch, and Cutter rigs.

A Fractional rig has forestays running from the bow to 1/4 – 1/8 from the top of the mast, and the spreaders are swept backward. A boat with a fractional rig also has the mast farther forward than a masthead rig, a bigger mainsail, and a smaller headsail, usually a Jib. Very typical on more performance-oriented sailboats.

There are exceptions in regards to the type of headsail, though. Many performance cruisers use a Genoa instead of a Jib , making the difference smaller.

Some people also fit an inner forestay, or a babystay, to allow flying a smaller staysail.

Explaining the parts and hardware of the standing rigging

The rigging on a sailing vessel relies on stays and shrouds in addition to many hardware parts to secure the mast properly. And we also have nautical terms for each of them. Since a system relies on every aspect of it to be in equally good condition, we want to familiarize ourselves with each part and understand its function.

Forestay and Backstay

The forestay is a wire that runs from the bow to the top of the mast. Some boats, like the Cutter rig, can have several additional inner forestays in different configurations.

The backstay is the wire that runs from the back of the boat to the top of the mast. Backstays have a tensioner, often hydraulic, to increase the tension when sailing upwind. Some rigs, like the Cutter, have running backstays and sometimes checkstays or runners, to support the rig.

The primary purpose of the forestay and backstay is to prevent the mast from moving fore and aft. The tensioner on the backstay also allows us to trim and tune the rig to get a better shape of the sails.

The shrouds are the wires or lines used on modern sailboats and yachts to support the mast from sideways motion.

There are usually four shrouds on each side of the vessel. They are connected to the side of the mast and run down to turnbuckles attached through toggles to the chainplates bolted on the deck.

- Cap shrouds run from the top of the mast to the deck, passing through the tips of the upper spreaders.

- Intermediate shrouds run from the lower part of the mast to the deck, passing through the lower set of spreaders.

- Lower shrouds are connected to the mast under the first spreader and run down to the deck – one fore and one aft on each side of the boat.

This configuration is called continuous rigging. We won’t go into the discontinuous rigging used on bigger boats in this guide, but if you are interested, you can read more about it here .

Shroud materials

Shrouds are usually made of 1 x 19 stainless steel wire. These wires are strong and relatively easy to install but are prone to stretch and corrosion to a certain degree. Another option is using stainless steel rods.

Rod rigging

Rod rigging has a stretch coefficient lower than wire but is more expensive and can be intricate to install. Alternatively, synthetic rigging is becoming more popular as it weighs less than wire and rods.

Synthetic rigging

Fibers like Dyneema and other aramids are lightweight and provide ultra-high tensile strength. However, they are expensive and much more vulnerable to chafing and UV damage than other options. In my opinion, they are best suited for racing and regatta-oriented sailboats.

Wire rigging

I recommend sticking to the classic 316-graded stainless steel wire rigging for cruising sailboats. It is also the most reasonable of the options. If you find yourself in trouble far from home, you are more likely to find replacement wire than another complex rigging type.

Relevant terms on sailboat rigging and hardware

The spreaders are the fins or wings that space the shrouds away from the mast. Most sailboats have at least one set, but some also have two or three. Once a vessel has more than three pairs of spreaders, we are probably talking about a big sailing yacht.

A turnbuckle is the fitting that connects the shrouds to the toggle and chainplate on the deck. These are adjustable, allowing you to tension the rig.

A chainplate is a metal plate bolted to a strong point on the deck or side of the hull. It is usually reinforced with a backing plate underneath to withstand the tension from the shrouds.

The term mast head should be distinct from the term masthead rigging. Out of context, the mast head is the top of the mast.

A toggle is a hardware fitting to connect the turnbuckles on the shrouds and the chainplate.

How tight should the standing rigging be?

It is essential to periodically check the tension of the standing rigging and make adjustments to ensure it is appropriately set. If the rig is too loose, it allows the mast to sway excessively, making the boat perform poorly.

You also risk applying a snatch load during a tack or a gybe which can damage the rig. On the other hand, if the standing rigging is too tight, it can strain the rig and the hull and lead to structural failure.

The standing rigging should be tightened enough to prevent the mast from bending sideways under any point of sail. If you can move the mast by pulling the cap shrouds by hand, the rigging is too loose and should be tensioned. Once the cap shrouds are tightened, follow up with the intermediates and finish with the lower shrouds. It is critical to tension the rig evenly on both sides.

The next you want to do is to take the boat out for a trip. Ensure that the mast isn’t bending over to the leeward side when you are sailing. A little movement in the leeward shrouds is normal, but they shouldn’t swing around. If the mast bends to the leeward side under load, the windward shrouds need to be tightened. Check the shrouds while sailing on both starboard and port tack.

Once the mast is in a column at any point of sail, your rigging should be tight and ready for action.

If you feel uncomfortable adjusting your rig, get a professional rigger to inspect and reset it.

How often should the standing rigging be replaced on a sailboat?

I asked the rigger who produced my new rig for Ellidah about how long I could expect my new rig to last, and he replied with the following:

The standing rigging should be replaced after 10 – 15 years, depending on how hard and often the boat has sailed. If it is well maintained and the vessel has sailed conservatively, it will probably last more than 20 years. However, corrosion or cracked strands indicate that the rig or parts are due for replacement regardless of age.

If you plan on doing extended offshore sailing and don’t know the age of your rig, I recommend replacing it even if it looks fine. This can be done without removing the mast from the boat while it is still in the water.

How much does it cost to replace the standing rigging?

The cost of replacing the standing rigging will vary greatly depending on the size of your boat and the location you get the job done. For my 41 feet sloop, I did most of the installation myself and paid approximately $4700 for the entire rig replacement.

Can Dyneema be used for standing rigging?

Dyneema is a durable synthetic fiber that can be used for standing rigging. Its low weight, and high tensile strength makes it especially popular amongst racers. Many cruisers also carry Dyneema onboard as spare parts for failing rigging.

How long does dyneema standing rigging last?

Dyneema rigging can outlast wire rigging if it doesn’t chafe on anything sharp. There are reports of Dyneema rigging lasting as long as 15 years, but manufacturers like Colligo claim their PVC shrink-wrapped lines should last 8 to 10 years. You can read more here .

Final words

Congratulations! By now, you should have a much better understanding of standing rigging on a sailboat. We’ve covered its purpose and its importance for performance and safety. While many types of rigs and variations exist, the hardware and concepts are often similar. Now it’s time to put your newfound knowledge into practice and set sail!

Or, if you’re not ready just yet, I recommend heading over to my following guide to learn more about running rigging on a sailboat.

Sharing is caring!

Skipper, Electrician and ROV Pilot

Robin is the founder and owner of Sailing Ellidah and has been living on his sailboat since 2019. He is currently on a journey to sail around the world and is passionate about writing his story and helpful content to inspire others who share his interest in sailing.

Very well written. Common sense layout with just enough photos and sketches. I enjoyed reading this article.

Thank you for the kind words.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

Global Solo Challenge: Standing rigging - Step by step guide on how to tune it on your sailboat

Related Articles

Practical Boat Owner

- Digital edition

How to set up your rig: tension your shrouds on masthead or fractional

- David Harding

- March 15, 2021

How to set up three common types of rig: the traditional masthead with a single set of in-line spreaders, single-spreader swept fractional rigs, and fractional rigs with two sets of swept spreaders. David Harding reports

How to set up your rig : tension your shrouds on masthead or fractional

If boats were cars, many of those I see sailing along would be coughing and spluttering down the motorway at 35mph in third gear with three flat tyres and a smoky exhaust. Others would cruise past in top gear at 70, making half the noise and using a fraction of the fuel.

Would these top-gear drivers be working any harder? Would they have cars that were faster by design and more expensive? Not at all. They would simply be the ones who had pumped up their tyres, learned their way around the gearbox and had their engines serviced.

It’s worth keeping an eye on your leeward cap shrouds during early-season outings after the mast has been re-stepped. The ones on this yacht could do with a little more tension

The obvious question, then, is why so many boat owners seem to leave their quest for efficiency and economy on the dockside.

One answer is that many are unaware how inefficiently their boats are performing. Another is that there’s no MOT for sailing boats and no driving test to make sure people know how to sail them (thank goodness on both counts).

Whatever the reasons, the fact remains that an efficient rig is fundamental. If the rig’s not right, the sails have no hope of setting properly.

And that’s important whether you’re racing or cruising, because sailors of both persuasions ultimately want the same: maximum lift for minimum drag.

For racers, that means more speed and better results. They carry more sail because they have more crew to handle it and more weight on the rail to balance it.

Cruisers carry less sail but, if it works efficiently, it means less heel, less leeway, better pointing, less tacking, a lighter helm and greater comfort than if it’s working inefficiently – plus the ability to get home before night falls or the pub shuts. Who can object to that?

What matters is that the sail you’re carrying is driving you forwards, not pushing you sideways.

When I question cruising sailors about the state of their rig I often get the reply ‘Oh it doesn’t matter – I’m not racing!’.

Those I know who have done something about it, however, have been delighted by the transformation their boats have undergone and have had to agree that cruising fast and comfortably is definitely better.

Setting up your boat rigging

In this article we’re going to look at how to set up the three most common types of rig: the traditional masthead with a single set of in-line spreaders, single-spreader swept fractional rigs, and fractional rigs with two sets of swept spreaders.

For simplicity we’re assuming the use of 1×19 rigging except where mentioned otherwise.

Variations in rig type are almost infinite by the time you take into account deck-stepped and keel-stepped masts, masthead rigs with swept spreaders, jumper struts, fractional rigs with in-line spreaders, and so on.

Once you understand the basics, however, you’ll find that you can apply your knowledge to good effect on most types of rig.

Rig-tuning is not only for the experts. Experience helps, of course, and a multiple-spreader fractional rig is harder to tune than an old tree-trunk of a masthead rig from the 1970s.

Nonetheless, with practice, a good eye and some observation you will probably find you can set it up pretty well.

You might want to call in a rigger or an experienced rig-tweaker to help or to do it for you the first time, and perhaps to check it periodically thereafter, but at least if you know what to look for you’ll notice when anything needs adjusting.

A word of warning when it comes to boatyards that have re-stepped your mast: sometimes re-stepping means just that and no more.

I have been on boats whose owners have assumed that the yard had set up the rig, whereas in fact it had just been dropped in and the bottlescrews hand-tensioned to stop it falling over.

It’s scary to think of the number of boats that must have been sailed in this condition.

What you will need to tune your rig Essential A calm day: don’t try setting up your rig in more than a few knots of wind A boat that’s floating level fore-and-aft (and preferably laterally as well) Screwdriver/lever bar Spanners (fixed or adjustable) Needle-nose pliers for split-pins Electrical insulation or self-amalgamating tape Lubricant for bottlescrews Tape measure (folding/small cassette type, or ideally folding rule) Useful Spring balance Long tape-measure Rig-tension gauge

The importance of enough tension: Why tight is right

If you think you’re being kind to your boat by leaving the rigging slack, think again. It’s true that some keelboats (such as Squibs and XODs) sail with the leeward cap shroud waving around in the wind, but that doesn’t work on yachts designed to go to sea.

Rigging that’s under-tensioned puts infinitely more load on the wire, bottlescrews, terminals and hull structure because of the snatch loads every time the boat falls off a wave. When it hits the bottom of the trough, anything that’s free to move gets thrown forwards and sideways before being brought up short by whatever happens to be in the way to stop it. That applies to the crew, to loose gear down below or to the mast. Think of the inertia to which a mast is subjected because of its height, and you can imagine the loads involved.

If the rigging is sensibly tight, on the other hand, movement and the consequent stresses are minimised.

Boats are built to withstand the static loads of a properly-tensioned rig, but asking them to cope with constant snatch loading is unfair – so don’t kill your boat with kindness.

As we discuss in the sections on the types of rig (below), masthead configurations with in-line spreaders need less cap-shroud tension than swept-spreader fractional rigs. This is because in-line caps are only supporting the mast laterally. The backstay stops it moving forwards, so each wire has a separate, clearly-defined role.

Aft-swept caps support the mast both laterally and fore-and-aft. Being swept aft typically about 25°, they need to be under a lot of tension to keep the forestay tight. Because they’re also at a much shallower angle to the mast, they bear between three and five times the load of the forestay.

With fractional rigs, then, it’s vital to keep the cap shrouds tight. If they’re too loose, the forestay will sag too much, the headsail will become too full and its leech will be too tight. Then the boat will become unbalanced, heel too far, make more leeway and lose both speed and pointing ability.

Structurally, under-tensioned rigging with a swept-spreader rig presents a problem in addition to the issue of snatch loading. Tension in the leeward cap shroud is important in keeping the mast in column, to the extent that Loos and Co (the manufacturer of the popular rig-tension gauges) states that a mast loses 50% of its lateral stiffness when the leeward cap goes slack. When this happens, the mast is effectively hinging around the forestay and the windward cap shroud and is far more prone to pumping as the boat bounces around.

The main reason why under-tensioned rigs on cruising boats stay standing as they do is that manufacturers build in enormous margins.

Even so, proper tension means better performance and greater safety. The ‘it doesn’t matter – I’m only cruising’ excuse for slack rigging just doesn’t cut it!

How to measure rig tension

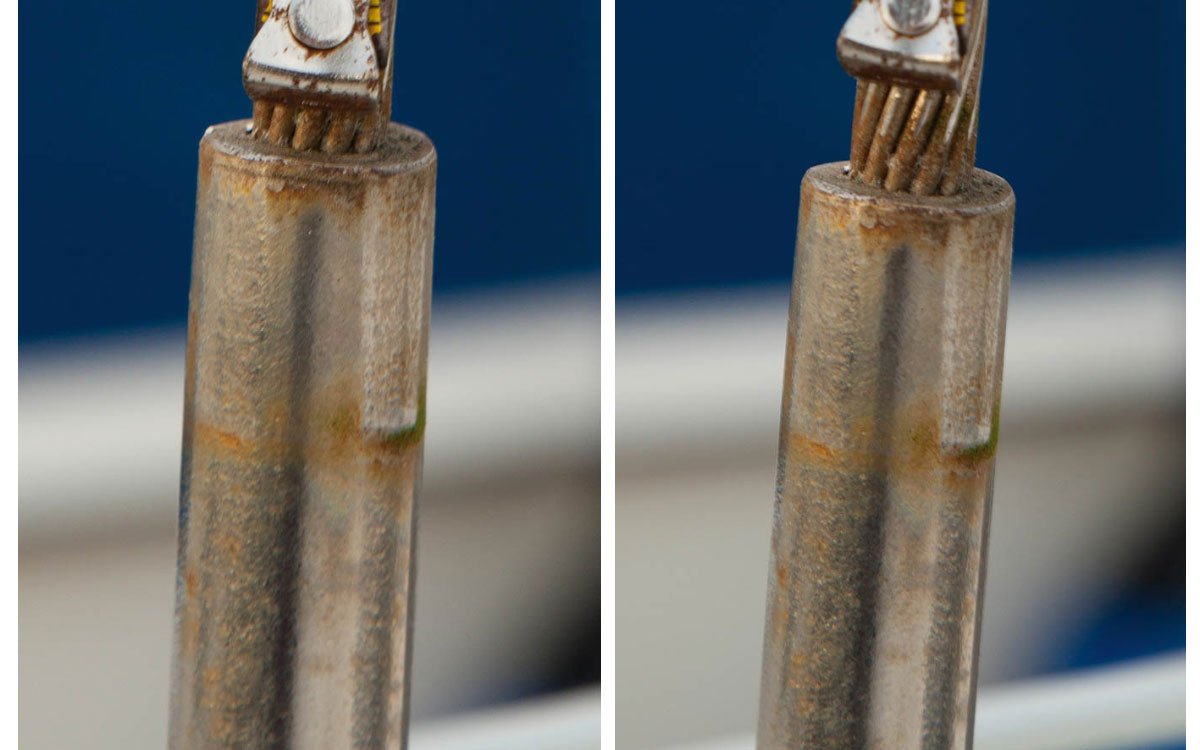

This Loos gauge (left image) is indicating that the 6mm wire in the cap shroud is at 22% of its breaking strain (730kg). To measure the stretch, extend a tape measure (right) (or ideally a folding rule) to 2,000mm and mark this distance up the wire…

…but start with the end of the tape a couple of millimetres above the top of the swaging. As the wire is tensioned it will stretch, increasing the gap below the end of the tape.

Experienced riggers and rig-tweakers will often tension the rigging at the dockside by feel, then sight up the mast and make any adjustments under way.

Most people aren’t confident enough to do this, though – so what are the best ways to check the tension as you wind down the bottlescrews?

The simplest and quickest way is to use a rig-tension meter, such as the Loos gauge. Once you know the diameter of the wire, it will give you the load both in kg and as a percentage of its breaking strain.

The gauge for rigging of 5m and 6mm (and up to 14% of breaking strain on 7mm) typically costs around £65, while the bigger version for wire from 7mm to 10mm is closer to £200.

If you don’t have a tension gauge, you can calculate the percentage of a wire’s breaking strain by measuring its stretch, normally over a distance of 2m: when 1×19 wire has stretched by 1mm over a 2,000mm length, it’s at 5% of its breaking load whatever its diameter.

Most cruising boats have rigging made from 1×19 wire. On sportier boats it might be Dyform or rod, in which case 5% of breaking load is indicated by stretch of 0.95 and 0.7mm respectively. For the purpose or our illustrations we’ll assume 1×19.

For accurate measurement the rigging needs to be completely slack. Hold the end of the tape a couple of millimetres above the top of the swaging, then measure 2,000mm up the wire, secure the other end of the tape here and start tensioning. When the gap between the top of the swaging and the end of the tape has increased by 1mm, you have reached 5% of the wire’s breaking strain, so 3mm equates to 15% and 5mm to 25%.

Bear in mind that 1×19 wire will be affected by bedding-in stretch during its first few outings, so new rigging will need to be re-tensioned a time or two during the first season.

Sensible precautions 1. Don’t force dry bottlescrews: keep them well lubricated. 2. Don’t use massively long tools for extra leverage on the bottlescrews. If you can feel the load, you’re less likely to strain or break anything. 3. Most boats will flex to some extent when the rig is properly tensioned. If you’re concerned about excessive bend, take it easy, use a straight edge across the deck to check for movement, and seek advice. 4. The percentages of breaking load quoted assume that the rigging is of the correct diameter as specified by the designer, builder or rigger.

How to set up a masthead rig with single in-line spreaders

This is the simplest type of rig to set up. Whether it’s keel-stepped or deck-stepped and supported by forward lowers or a babystay, it’s the same basic procedure.

Step 1: Get the mast upright athwartships

Measure the distance to fixed points on both sides that are symmetrical about the centreline, such as the base of the chainplates.

If you don’t have a long tape measure, use the halyard itself (this is where a spring balance can help you gauge the same tension on each side).

Centre the masthead by adjusting the port and starboard cap shrouds until the measurements are the same, then hand-tighten the bottlescrews by taking the same number of turns on each side.

Re-check and adjust as necessary.

A long tape measure is useful for getting the mast upright.

Step 2: Setting the rake

Rake is determined principally by the length of the forestay. Some roller-reefing systems allow no adjustment but you can increase length by adding toggles.

Adjust the forestay and backstay, checking the rake with a weight suspended from the end of the main halyard. One degree of rake is about 6in (15cm) in 30ft (9m).

Hand-tight on the backstay’s bottlescrew (or gentle use of the tensioner) is fine at this stage.

Rake is measured from the aft face of the mast, at or below boom-level. If the boat’s rocking around, suspend the weight in a bucket of water to dampen the movement.

Step 3: Tighten the cap shrouds and backstay

Take no more than two or three full turns on one side before doing the same on the other.

Count carefully.

You’re aiming to tension the caps to 15% of their breaking strain, measured as explained on page 41.

That might be much tighter than you’ve ever had them before!

Tension the backstay to 15% of its breaking load.

Note: Using ordinary hand-tools on the bottlescrews, it’s hard to over-tension the rigging

Step 4: Tighten the lowers / babystay

A mast should bend forward in the middle, though only to a small extent on masthead rigs of heavy section.

This ‘pre-bend’ is principally to counter two factors in heavy weather: increased forestay loads pulling the top of the mast forward, and the head of a reefed mainsail pulling the middle aft.

Together, they can result in the middle of the mast bowing aft, which makes it unstable and is bad for sail trim. For maximum strength in extremis it should be straight.

Use the forward lowers or babystay to pull the middle of the mast forward. The bend thus induced should be no more than half the mast’s fore-and-aft measurement.

Then take up the slack in the aft lowers.

They don’t need to be tight; they’re just countering the forward pull.

Sight up the luff groove to make sure the mast is straight laterally. Correct any deflections with the lowers.

If you set up the caps properly to start with, you should not adjust them again at this stage.

Step 5: Check the rig under sail

First, make sure the leeward cap shroud isn’t waving around in the breeze. You should be able to deflect it with a finger by a few inches; no more.

If it’s too loose, take a turn or two on the leeward bottlescrew, then tack and do the same on the other side.

Now sight up the back of the mast.

It should be straight athwartships and bending slightly forward in the middle.

Athwartships deflection might make it look as though the top is falling away to one side (see diagram), but it won’t be if it was centred properly in Step 1. Straighten the middle by adjusting the lowers

If it’s straight or bending aft in the middle, try increasing the backstay tension (but not beyond 30% of its breaking strain) and, if necessary, tensioning the forward lowers/babystay and slackening the aft lowers.

Remove any lateral bends by adjusting the lowers.

Once you’re happy, lock off the bottlescrews to make sure they can’t come undone.

Inverted bend (mast bowing aft in the middle) is bad for sail trim and potentially dangerous for the rig.

Setting up a fractional rig with single, aft-swept spreaders

Widely used on smaller cruisers and cruiser/racers, this configuration needs a very different approach from an in-line masthead rig

This stage is the same as with a masthead rig (scroll up).

Step 2: Set the rake

This time, however, rake is set by the forestay and cap shrouds rather than the forestay and backstay.

With a swept-spreader fractional rig it’s the cap shrouds, not the backstay, that stop the mast moving forward. They provide both fore-and-aft and lateral support, so they’re doing two jobs.

The backstay’s principal role is to control the topmast and mast-bend. Because it’s above the point where the forestay joins the mast, it’s not pulling directly against the forestay and therefore has less effect on forestay tension. How much it pulls against the forestay depends on factors including the height of the topmast, the stiffness of the mast section and the tension of the lower shrouds (which determine the bend).

Step 3: Tighten the cap shrouds

Forestay tension is achieved primarily through the caps, and because they’re swept back at such a shallow angle they need to be seriously tight.

Their maximum tension is 25% of breaking load, but it’s best not to tension them all the way in one go because that would result in a very bent mast: tensioning the caps pushes the spreaders, and therefore the middle of the mast, forward.

Start by taking them to about 15% of breaking load, then tighten the lowers to pull the middle of the mast back so it’s straight.

This is how the swept-spreader fractional rig works: the caps and lowers are working against each other, caps pushing and lowers pulling, to stabilise the middle of the mast. Sight up the mast when it’s straight to check for lateral deflection, correcting it with the lowers.

With a flexible mast you might need to repeat the process, taking the caps to 20% before tensioning the lowers again.

Otherwise go straight to the next stage, which is to pull on the backstay.

Since the backstays on fractional rigs often have cascade purchases at the bottom you can’t measure the tension by stretch as you can with wire, so you have to do this by feel: pull it tight, but don’t go mad.

Tensioning the backstay bends the mast and therefore shortens the distance from the hounds (where the caps join) to the deck. This loosens the caps, so it’s easier to tension them back to the 20% mark.

When you let the backstay off, the caps will tension again and should be at about 25% of breaking load – but no more.

Step 4: Set the pre-bend

Take a few turns on the lowers to achieve the right amount of pre-bend. It should be more than with an in-line masthead rig, but a mast should never bend to more than 2% of the height of the foretriangle even with the backstay tensioned (that’s about 180mm in 9m, or 7in in 30ft).

Check to see how far the mast bends with a tight backstay. The optimum bend will often be determined by the cut of the mainsail, or recommended by the sailmaker or class association.

Pre-bend is vital because most fractional rigs don’t have forward lowers or a babystay, so if the mast were to bend aft in the middle (inverted bend) it could collapse.

In fresh conditions, especially under spinnaker, it’s a wise precaution never to release the backstay completely. That stops the upper section of the mast being pulled too far forward.

The caps should be tighter than with a masthead rig, with no significant slack on the leeward side when the boat’s hard on the wind and heeling 15-20°.

If the static tension is up to 25% but the leeward cap is always slack, the boat might be bending. That’s a topic beyond the scope of this article!

Sight up the mast to check the bend both fore-and-aft and athwartships, adjusting the lowers as necessary.

Setting up a fractional rig with two sets of aft-swept spreaders

As mast sections have become slimmer, this is now a popular configuration on boats between 30ft (9m) and 40ft (12m) but it’s more complex to tune.

This stage is the same as with the other types of rig.

Follow the procedure as described for single-spreader fractional rigs. Generally speaking, more rake improves upwind performance but too much will induce excessive weather helm and hamper performance downwind. Getting it right might involve some trial and error.

Steps 3 & 4: Tighten the caps and set the bend

The same fundamentals apply as for a single-spreader rig, but this time after each tensioning of the cap shrouds, which induces bend, you have to straighten the mast by tensioning both the lowers (also known as D1s) and the intermediates (D2s).

The D1s control the bend between the deck and the upper spreaders and the D2s between the lower spreaders and the hounds, so their areas of influence overlap.

On boats where the D2s terminate at the lower spreaders you have to send someone aloft to adjust them. These are referred to as discontinuous intermediates.

If they run over the spreader tips and down to the chainplates (continuous intermediates) you can do everything from on deck.

You need to achieve an even bend fore-and-aft. If the mast is bending too much at the bottom and is too straight at the top, tighten the D1s and slacken the D2s.

S-bends can creep in athwartships and make it look as though the top of the mast is off-centre. If you set up the cap shrouds properly it shouldn’t be, so don’t fiddle with them any further now: take out the bends with the D1s and D2s.

You’re aiming for a cap-shroud tension of 20-25% of breaking strain, as with a single-spreader fractional rig, and again the sweep-back of the spreader means that the caps will be slackened as you pull on the backstay.

As with other types of rig, get the boat heeling around 20° on the wind, tension the backstay and feel the leeward cap to make sure there’s only minimal slack.

Removing any kinks and S-bends can take more tweaking of lowers and intermediates, the latter being more fiddly to adjust if they’re discontinuous.

If the masthead looks as though it’s falling off one way, it’s probably because the D2 on the opposite side is too tight.

Left: Windward lower too loose. Right: Windward intermediate too tight.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the May 2012 edition of Practical Boat Owner . For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

Hunter 35.5 Legend Used Boat Review

Pearson Rhodes 41/Rhodes Bounty II Used Sailboat Review

Hallberg-Rassy 42 Used Sailboat Review

How to Perform Your Own Pre-Buy Inspection

Thinking Through a Solar Power Installation

How Does the Gulf Stream Influence our Weather?

Can You Run a Marine Air-Conditioner on Battery Power?

Preparing Yourself for Solo Sailing

Practical Sailor Classic: The Load on Your Rode

Anchor Rodes for Smaller Sailboats

Ground Tackle Inspection Tips

Shoe Goo II Excels for Quick Sail Repairs

Diesel Performance Additives

What Oil Analysis Reveals About Your Engine

Painting a New Bootstripe Like a Pro

Penetrating Epoxy—Another Marketing Gimmick?

The Best Tools for Bottom Painting

The Hidden Maintenance Problems That Can Ruin Your Day: Part 1

Alcohol Stoves— Swan Song or Rebirth?

Living Aboard with an Alcohol Stove

Choosing the Right Fuel for Your Alcohol Stove

How to Select Crew for a Passage or Delivery

Preparing A Boat to Sail Solo

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Sails, Rigging & Deck Gear

Standing Rigging: How Tight Is Right?

Standing rigging tension is a peculiarly under-addressed subject. Easy to see how it would worry a new boat owner or someone going to sea.

Most experts step aboard, yank or twang the shrouds and stays and mutter, Pretty slack, Too Tight, or, Thats about right.

Youll find in the sailing literature very few discussions of the question: What does tight mean?

Even riggers rarely explain how much tension they like to see.

There are a few sailors who like the rigging so tight you could send an elephant up the backstay. It can result in excessive loads and wear on fittings, chain plates and the hull. The ultimate penalty for those who can’t stand any sag in the forestay is what ocean racing sailors call a gravity storm or, less dramatically, dropping the rig.

Others like to take up the slack just enough so that the rig is at rest when the boat is motionless. This approach sometimes leaves excessive slack to leeward that can result in shock loads, excessive wear and misalignment in fittings. It may take longer, but the ultimate penalty is the same.

In between (and probably in the most logical position) are those who like to take up the slack and stretch the wire just a bit. This is frequently accomplished, at least for the stays, with an adjustable backstay. When sailing, especially on the wind, tighten down to minimize slack in the forestay. When reaching, running or at anchor, ease off.

But the question is: How much stretch…especially in the shrouds?

If you stretch the wire 5% of its breaking strength, it will be considered moderate tension. Crank in 15% of the breaking strength and it is regarded as tight. These figures apply for any diameter of wire. You need only know the wires breaking strength.

Three years ago, in the June 15, 1995 issue, we published a discussion of the views of author Richard Henderson, Skenes Elements of Yacht Design and several riggers, along with an evaluation of an excellent booklet published by Sailsystems about a Selden Mast approach (described in detail in the October 15, 1991 issue) and an entirely new method developed by Michael Dimen, who called his gadget a Rigstick.

Mentioned was the familiar (see photo) Loos rigging tension gauge, which comes in two sizes. The Model 91 ($39) is for wire 3/32″ to 5/32″. The Model 90 ($45.50) is for 3/16″ to 9/32″. The gauge depends on the bending property of aluminum plate.

The strange-looking gauges don’t willingly produce great accuracy because you have to hold one reading steady while noting another, which also requires that you make a judgment about where the centerline of the wire falls on a scale. Not easy to do.

The big name in galvanized and stainless cable (as wire is called in the trade), cable hardware and tools, Loos & Co., Inc. went looking for a better mousetrap.

Who did Gus Loos go to? The guy who designed the original gauge, his old friend, Donald J. Jordan, an 82-year-old retired Pratt & Whitney engineer who has been sailing out of Marblehead, Massachusetts, in the likes of Lightnings, Friendship sloops, Sound Schooners (which was the prized New York Yacht Club class in 1918), Pearson Wanderers and currently in a 16′ Starling Burgess design, appropriately called a Marblehead.

The old tension gauge wasnt bad, said Jordan. But it tended to get bent. Then the patent ran out and I told Gus we could do a better one.

The new version (see photo) is a distinct improvement over the old aluminum version. A better design, its also much more substantially made of aluminum, stainless and nylon.

The design problems were interesting, Jordan said. A conventional cable tension gauge has two rollers at the ends with a spring-loaded plunger in the middle and a dial gauge to measure the plunger movement. The wheels have to rotate…because they must permit some small but vital movement. That makes the tool expensive. My approach was to have two stationary wheels and a carefully contrived square slider in a arc-slot on the other.

The new Loos gauges use a long-lasting stainless spring to produce the tension. Slip the lower grooved wheels on a shroud or stay, pull the lanyard to engage the upper hook, relax, read the tension at your leisure and consult the scale to learn the pounds of pressure on the wire and the percentage of breaking strength of the wire. There are three wire gauge notches in the edge. The gauge can be left on the wire while turnbuckle adjustments are made.

The accompanying booklet, very well-done, contains a good tight discussion of the subject; some recommendations; a table on how to equalize tension in different sizes of wire, and line-drawn diagrams clearly showing rig tensions (windward and leeward) created by light, medium and heavy winds.

The wire gauge comes in three sizes, for 3/32″-5/32″, 3/16″-1/4″ and 9/32″-3/8″. West Marine sells them, respectively, for $57.99, $69.99 and $$122.99. Defender Industries cuts them to $49.95, $51.95 and $105.95. Prices in the BOAT/U.S. catalog are in between.

What if, instead of 1×19 wire, you have rod rigging? There are four new models that are bigger, heavier and, of course, more costly. They work the same, but take some arm strength. One is for .172-.250 rod, another for .281-.375. Two others models are for metric rod. West Marine sells the rod gauges for $186.99. Neither Defender nor BOAT/U.S. shows them in their catalogs.

Contact- Loos & Co., Inc., 901 Industrial Blvd., Naples, FL 34104, 800/321-5667. Rigstick, 311 Jackson, Port Townsend, WA 98368; 800/488-0855. Sailsystems, PO Box 1218, Marblehead, MA 01945; 978/745-0440.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

An Italian Go Fast Sailboat – The Viko S 35 |...

What Is The Best Folding Bike For Your Sailboat?

The No Expense Spared Antigua 60 Cruising Sailboat Soolaimon

How To Buy Sails – With Joe Cooper

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

James Suggitt

David Flynn

The backstay is a powerful tool and you should introduce it to your toolbox for more than just keeping the rig in the boat. No matter what the rig type or stiffness the tensioning the backstay keeps the headstay from sagging. Headstay sag equals extra power in the headsail, so when you don’t want the power (heeling too much) use the backstay. On boats with rigs that bend, the backstay helps depower the mainsail. When you add backstay tension on this type of rig you are essentially compressing a straw. The mast bends forward at the middle pulling the luff away from the leech thereby flattening the sail. It is a hugely powerful tool which allows you take your mainsail from full and powerful in light air to flat and open in the leech for windier conditions. As the breeze builds and you start to generate too much heel and helm use your backstay!

The Discussion

This website uses cookies and collects usage statistics. Privacy Policy

Us, too. We pour that passion into each of our newsletters to help you enjoy sailing even more.

Fractional Rig: Everything You Need to Know

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 21, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer fractional rig:

A fractional rig is a sailboat mast configuration where the forestay (the wire or rope that supports the mast from the front) attaches to a point lower on the mast than its highest point. This design allows for greater control over sail shape and is commonly found in high-performance racing boats.

Understanding Fractional Rig: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction: Sailing is an art that requires a deep understanding of boats, their components, and how they work together to harness the power of the wind. One essential aspect of sailboat design is the rigging system, which plays a crucial role in determining a boat’s performance and handling characteristics. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the world of fractional rigs – their purpose, composition, advantages, and tips for optimizing their use on the water.

What is a Fractional Rig? A fractional rig refers to a sailboat’s mast setup where the forestay (the wire or cable running from the top of the mast to the bow) does not intersect with the mast at its top point. Instead, it attaches at some point below it. This configuration creates two distinct sections in terms of percentage height: one shorter section above and one longer section below this intersection point – usually around 7/8 or 9/10 up the mast’s length.

The Purpose and Advantages of a Fractional Rig: 1. Versatility: The fractional rig is highly versatile as it allows sailors to adjust sail area quickly according to changing weather conditions while maintaining balance and control. 2. Enhanced Performance: Due to its ability to distribute loads more evenly along the mast, a fractional rig enables increased stability and reduced pitching moment during strong winds. 3. Improved Upwind Performance: By positioning more sail area forward compared to other rig configurations like masthead rigs, fractional rigs generate better drive upwind resulting in higher pointing angles. 4. Simplified Sail Handling: With lesser reliance on heavy overlapping headsails common in conventional rigs, managing sails becomes less physically demanding during maneuvers such as tacking or reefing.

Components of a Fractional Rig: 1. Mast Section: The mast used in fractional rigs often has slightly different dimensions than those employed in other systems due to its specialized function. Its shorter upper section allows for better control of the mainsail’s shape, while the longer lower section offers increased downwind power. 2. Forestay: The forestay is connected to the mast below its top point and usually runs from a fitting on deck to secure bow fittings. Its angle and tension can be adjusted to optimize sail trim and overall rig balance. 3. Backstay: Unlike a conventional rig where the backstay connects at the masthead, in fractional rigs, it attaches lower down – generally above or just below the intersection point with the forestay. Adjusting its tension further influences mast bend and sail shape .