How to Create a Jury Rig

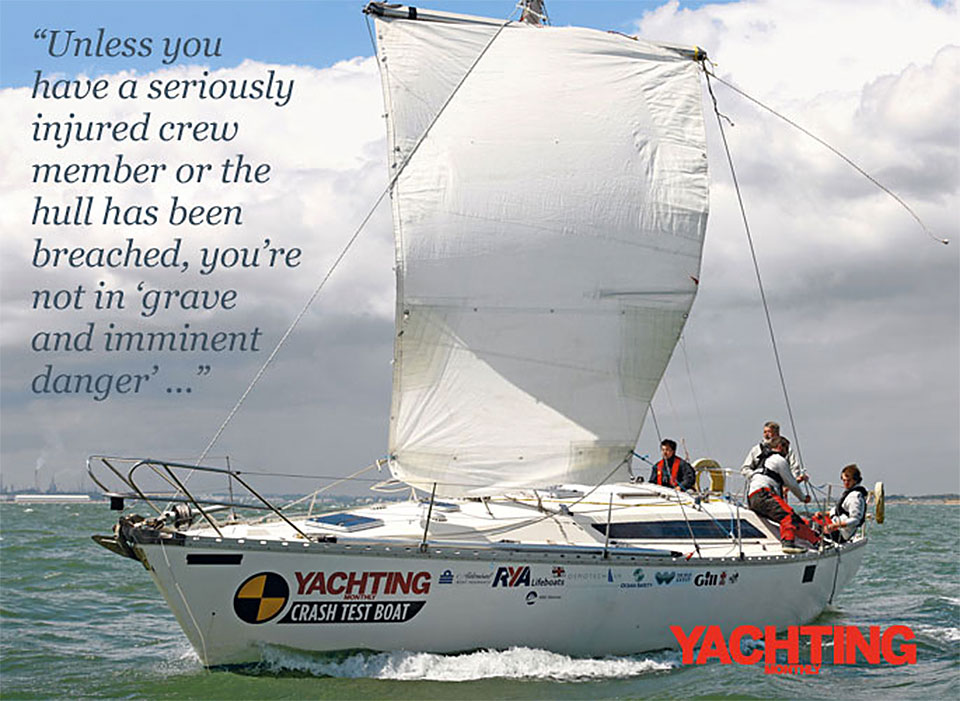

In association with Admiral Boat Insurance, Yachting Monthly created a series of potential disasters to find out if all the theories of how to deal with such situations actually work in practice. The boat used in the crash test is Admiral’s own 1982 Jeanneau Sun Fizz ketch, Fizzical .

Once the poor Crash Test Boat had lost her mast, it was time to set up a jury rig. The Crash test team demonstrated how to do this by using nothing that wasn’t on the boat already. They used the stump of the mast which they had retrieved from the water, the main boom as a yard, and they re-cut the damaged mainsail to a square sail to effect at square rigger. Using spare shackles they created a tripod of stays, running a forestay from the masthead through a block at the stemhead where this would carry the greatest load, and two shrouds, run from the masthead through two blocks lashed to toerails aft of the mast step. The new square sail was lashed to the boom which was raised to the top of the mast square across it, the forward clew lashed forward, and the aft clew used as a sort of main sheet. Various adjustments were needed to get her to sail close to the wind including adding the original small jib as a trysail. The team explains in their article (see the August 2011 issue of Yachting Monthly below) how this was done.

Following last month’s dismasting of the Crash Test Boat by Yachting Monthly, the unlucky crew set about creating a jury rig from what was left on board. This resulted in the elegant square rigger shown above. Below is a video of the event itself.

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube’s privacy policy. Learn more

Always unblock YouTube

Robert Holbrook, MD Admiral Marine

“Often, the first natural human instinct when an emergency or disaster strikes is panic. In a series of controlled experiments, the Yachting Monthly crew put theory to the test by re-enacting some typical worst-case scenario sailing accidents or emergencies – such as grounding, capsize and mast failure. Risk assessment and careful consultation with experts was at the core of all tests. How often are incidents like this photographed and filmed in detail? By sharing their findings in a series of articles, I could see how yachtsmen could learn much invaluable information. Why not learn from our mistakes by following her story so you can avoid making your own?”

All Yacht Monthly articles are available in full

Download the full, unabridged yachting monthly articles in pdf format below for reading at your leisure..

What to do When your Yacht Run Aground: Yachting Monthly Article (PDF)

Dismasting: Yachting Monthly Article (PDF)

Boat Leaking – The Best Ways to Plug a Broken Through Hull from Yachting Monthly: Yachting Monthly Article (PDF)

Capsizing: Yachting Monthly Article (PDF)

Gas Explosion: Yachting Monthly Article (PDF)

Sinking: Yachting Monthly Article (PDF)

Admiral Marine is a trading name of Admiral Marine Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FRN 306002) for general insurance business. Registered in England and Wales Company No. 02666794 at Beacon Tower, Colston Street, Bristol BS1 4XE.

If you wish to register a complaint, please contact the Compliance and Training Manager on [email protected] . If you are unsatisfied with how your complaint has been dealt with, you may be able to refer your complaint to the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS). The FOS website is www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk

Boatbuilders

Useful links, yachts & boats we insure.

+44 (0)1722 416106 | [email protected] | Blakey Road, Salisbury, SP1 2LP, United Kingdom

Part of the Hayes Parsons Group

Running Rigging vs. Standing Rigging vs. Jury Rigging

On ships, running rigging changes a lot as a voyage goes on and needs to be flexible in that way. Standing rigging can also be called static rigging, as it stays put once it is set up.

A jury-rigging is also referred to as makeshift rigging, temporary rigging, or emergency rigging. Jury-rigging should be employed only as a temporary fix and should never be used in place of long-term maintenance or repairs.

Table of Contents

What Rigging means

Rigging is the term used to describe any system of ropes, cables, wires, and other components that are used to support and stabilize a boat.

Rigging can be done in many different ways and can vary in color, size, level of complexity, and the materials used.

Rigging is vital to ensure a boat remains stable and secure while out on the water.

Running Rigging

Running rigging refers to the ropes and cables that are used on boats and other sailing vessels to move and control the sails, masts, yards, booms, and other parts of the vessel.

It is a system of ropes that can be adjusted to change the level of the sails and masts in order to control the direction and speed of the boat.

Running rigging comes in various sizes, materials, and colors and must be checked regularly for wear or fraying.

It is important to maintain the running rigging to ensure that the vessel is safe and seaworthy.

Two types of running rigging

Running rigging is the collection of lines, wires, and other hardware used to move, control, and adjust sails while a boat is underway.

There are two main types of running rigging used on sailboats: halyards and sheets.

A halyard is used to raise and lower sails.

It can be made of rope or wire and attached to the sail head. The sail can be easily raised and lowered this way.

Sheets are used to controlling the angle of the sail.

This is done by connecting one end of the sheet to the clew of the sail, while the other end runs through a series of blocks and leads back to the cockpit.

This allows the sailor to adjust the angle of the sail to maximize performance and speed.

What color scheme is running rigging?

The color scheme for running rigging varies depending on the type of boat and sailing setup.

For example, a sloop rigged boat would usually have two halyards – one that is red, and one that is white. Additionally, sail sheets typically come in black, blue, green, or yellow.

On boats with more than one mast, there are often color-coded lines to distinguish them. For example, the halyard on the mizzenmast could be green while the mainmast’s halyard is red.

On boats with multiple sails, the sheets will also be color-coded. Additionally, boats typically feature a colored marker at the end of the rope or sheet to easily identify it.

When using a multi-color system for rigging, it’s important to know the exact purpose and location of each line to avoid confusion.

The color coding is a helpful tool to ensure the lines are used correctly and efficiently.

Is a spinnaker pole running rigging?

A spinnaker pole is a piece of running rigging on a sailboat. It is used to help control and shape the spinnaker or other large headsails, especially when sailing downwind.

The spinnaker pole is attached to the mast by one end and then extended outward. The spinnaker is then hoisted to the other end of the pole and the tension of the sail is adjusted to the desired setting.

The spinnaker pole also helps to keep the sail filled with wind, which increases the boat’s speed.

What kind of rope do you use for running rigging?

Ideally, you should choose a rope that is both strong and lightweight. The most commonly used types of rope for running rigging are polyester, Dyneema, or Spectra.

Polyester is typically the cheapest option, so it’s often used by beginner sailors. Polyester has decent strength and low-stretch properties, but it’s heavier than the other two options.

Dyneema and Spectra are made from ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE). Both of these ropes have high strength and extremely low-stretch properties.

They are more expensive than polyester but much lighter and more durable. In addition, they are less prone to abrasion than polyester.

No matter which type of rope you choose, make sure it is specifically designed for marine use and that it is properly sized for the job.

What does colors running mean?

When it comes to running rigging, the term “colors running” is commonly used. Colors running refers to how a rope is marked to indicate its intended use.

Generally, the rope is wrapped in a colored webbing or twine and knotted in specific ways to signify its purpose.

For example, a red line may be used for halyards, blue for sheets, and green for reefing lines. This makes it easier for sailors to identify the correct line quickly, especially in an emergency situation.

Additionally, having distinct colors helps reduce confusion on board and prevents mistakes from occurring when rigging and unrigging.

Knowing the various color schemes associated with different types of rigging is essential to safe sailing.

Standing Rigging

Standing rigging refers to the permanent lines used on a sailing vessel, like the main mast and the shrouds.

These lines hold the masts in place and are used to support the sails and other components of the boat.

The standing rigging is usually made of high-quality stainless steel wire rope, although some modern boats also use synthetic rigging materials.

Standing rigging is generally replaced every few years to ensure the safety of the rig and to ensure that the boat continues to perform as intended.

The standing rigging will generally consist of halyards, forestays, backstays, and side stays.

These lines can be adjusted for different conditions and will help adjust the amount of sail tension being placed on the masts.

On some boats, there may also be a cap shroud or topping lift which helps hold the boom in place when sailing upwind.

Standing rigging should always be checked before each voyage to ensure that it is properly adjusted and secure.

What are the different types of standing rigging?

Standing rigging refers to the network of ropes, wires, or cables that are used to support and stabilize a sailing vessel.

Standing rigging is usually in place before the boat sets sail and should remain so until the boat docks again.

The standing rigging includes lines running from the masthead to the deck, as well as from the masthead to the sides of the boat.

The three main types of standing rigging are shrouds, stays, and forestays.

Shrouds are the lines running from the masthead to the deck.

They provide lateral support for the mast and keep it from moving around too much in heavy winds. It’s important to note that different types of boats may have different numbers of shrouds.

Stays are the lines running from the masthead to the sides of the boat.

Stays provide forward and backward support for the mast and can be adjusted to affect the shape of the sails. They also make sure that the boat points in the right direction while sailing.

Forestays are similar to stays, but they run from the front of the masthead to a point near the bow of the boat.

These lines provide tension on the mast and keep it from falling over while under sail.

It’s important to regularly inspect your standing rigging to make sure everything is secure and in good condition. This will help ensure that your sailing experience is a safe one!

Jury Rigging

Jury rigging is the improvised use of available materials to repair or replace damaged items or parts of a structure.

It is commonly used on sailing vessels in order to keep them afloat or to make temporary repairs until more permanent solutions can be found.

Jury rigging is often used when the proper tools and materials are not available for making a more permanent repair.

Jury rigging is also known as “makeshift rigging”, “temporary rigging”, or “emergency rigging”.

It involves the use of ropes, wires, and other materials to temporarily hold together items that are damaged or broken.

It is important to note that jury-rigging should only be done as a temporary fix and should never be used as a substitute for long-term maintenance or repairs.

Jury rigging can be used for a variety of tasks on a boat. It can be used to replace torn sails or broken masts, and it can even be used to build makeshift rudders and steerage systems.

In extreme cases, jury-rigging can be used to make watertight patches for leaking hulls.

It is important for sailors to understand the basics of jury-rigging and how to properly use it in order to stay safe on the water.

The main principles of jury-rigging are to think ahead, act quickly, and keep safety in mind at all times.

Standing vs. Running rigging

Standing rigging is the system of cables, wires, and other items used to support the masts and yards on a sailing vessel.

It is typically made of steel or stainless-steel cable or rod and is usually attached to the mast at the deck level.

Standing rigging is also known as “static rigging” because it remains in place once it’s set up.

Running rigging, on the other hand, is designed to be adjustable and often changes during a voyage.

This type of rigging consists of halyards, sheets, braces, and other equipment that sailors can adjust to help them maneuver the sails.

Running rigging is usually made of rope, and its primary purpose is to manage the sails.

The two types of rigging serve different purposes and are used in combination to maximize a vessel’s performance.

Standing rigging provides a sturdy structure while running rigging allows a sailor to control the sails.

Lifting vs. Rigging

Lifting and rigging are two different aspects of the same concept.

Lifting is used to move a heavy or large object from one location to another, usually via hoisting, lifting gear, or crane.

Rigging is the system of ropes, cables, chains, and other components used to support or control the weight or load while it is being lifted.

Lifting focuses on the object itself, and the mechanical process of moving it from one place to another. The size, shape, and weight of the object determine the type of equipment used for the job.

The material used for lifting can range from a crane to a forklift, depending on the task.

Rigging is used to help control the object while it is being lifted.

This can involve controlling its speed or direction, preventing it from swaying or swinging, and ensuring it is securely attached to the lifting device.

For this purpose, various materials can be used such as wire rope, webbing, chains, and rope slings.

Rigging equipment is also used for securing large objects during transport, such as on cargo ships or trailers.

What are the 4 basic rules of rigging?

1. Make sure all loads are evenly distributed.

When rigging, it is important to ensure that all loads are evenly distributed, so that no single point is carrying more weight than it should be.

This will ensure that no part of the system is over-stressed and is less likely to fail.

2. Don’t rig under tension.

Before you start rigging, make sure all parts of the system are slack and not under tension. Rigging with tension can cause excessive strain on the system and could lead to failure.

3. Use proper rigging techniques.

Always follow the proper rigging techniques for each type of system and configuration. Not following these techniques can lead to accidents and injury, as well as damage to the rigging system itself.

4. Safety first.

Above all else, make sure your rigging system is safe. Do not cut corners or take shortcuts that could put yourself or anyone else in danger.

Follow safety protocols and never take risks with rigging.

- Construction

- Optimisations

- Performance

- Equipment care

- Provisioning

- Keeping afloat

- Precautions

Jury steering, preparing for and dealing with a steering mechanism failure

What is the issue, why address this, how to address this.

With thanks to:

Add your review or comment:

Please log in to leave a review of this tip.

eOceanic makes no guarantee of the validity of this information, you must read our legal page . However, we ask you to help us increase accuracy. If you spot an inaccuracy or an omission on this page please contact us and we will be delighted to rectify it. Don't forget to help us by sharing your own experience .

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Dismasted offshore: how one man got his boat home

- Katy Stickland

- February 8, 2022

When Jock Hamilton’s 33ft Wauquiez Gladiateur dismasted offshore, 500 miles from land, he created a jury rig using a Laser dinghy mast, sails and oars, before sailing 1,500 miles home

Jock arriving home in Tighnabruaich after sailing 1,500 miles under jury rig. Credit: Jock Hamilton

Bang! I turned around just in time to see the mast of the boat toppling into the water over the starboard side, writes Jock Hamilton .

Bother! I’m 500 miles from anywhere in the North Atlantic. Is it causing damage? These thoughts passed through my mind as I clambered on deck to assess the situation and to attempt to free the mast from the boat.

Heading up the port side, I noticed that a broken deck fitting , to which the port lower shroud had been attached, was the cause.

The boom was largely on the starboard side deck; the mast was ‘sawing’ back and forth across the port guard rail – now an inch above the deck but still taking the strain.

The weather was moderate, about 20 knots of wind with 3m of sea or swell. Having been beating into it, now that we were lying still, conditions seemed a little less severe.

Jock’s route showing where he was dismasted offshore and his return voyage home. Credit: Maxine Heath

Freya , a Wauquiez Gladiateur, was now sitting across the wind, with the mast acting as a sea anchor to windward, and rolling quickly.

As I was at the port cap shroud, I disconnected this by pulling the small split pin out of the rigging pin with my multitool – a fixture on my belt for 21 years – and knocked out the big pin.

Then I crawled forward – carefully due to the rolling and lack of anything above deck level to hang onto.

The inner forestay was simple to detach from the highfield lever, and quickly despatched.

I thought I should detach the boom and try to salvage what I could. The situation seemed stable.

It was relatively easy to cut the leech reefing points, stick a figure of eight in the ends, cut the lazy jacks and cut the sail tape attaching the clew to the outhaul slider.

Under full sail with the jury rig set up after being dismasted offshore. Credit: Jock Hamilton

Moving to the gooseneck I cut the mainsail tack lashing and removed the pin on the gooseneck fitting.

Stupidly I took the rod kicker off at the boom, which meant I lost it with the mast.

With hindsight, I could have taken it off at the mast with a bit of careful work but it was a couple of feet in the air and moving up and down as the boat rolled.

Going aft I thought about taking the pin out from the bottom of the hydraulic backstay tensioner but decided; ‘No, save it’.

This involved taking some seizing wire from the bottlescrew and unscrewing that.

Dismasted offshore: Mast jettison

It was time to get rid of the mast. The forestay fitting went without trouble, again the multitool being adequate firepower for the task.

The mast was now held only by the starboard cap and lower shroud.

The lower went easily enough but I had placed white plastic pipes over the cap shrouds to assist in tacking the genoa and this still covered the deck fitting – it was bent and crushed over the guardrail and prevented me from accessing the attachment point.

Timing the effort, I pushed the bent gutter pipe out over the guardrail enough to access the deck fitting and wire. I had to be careful as I was close to the mast foot which was moving up and down as Freya rolled, threatening a possible injury.

The mast cleared from deck. Note the missing deck fitting, bottom left. Credit: Jock Hamilton

I’d heard in the past that the final fitting would have tension on it and needed to be cut; I used bolt croppers, a hacksaw and a grinder.

In the event, however, it seemed to be more practical to knock the pin out – the same as the others – and time it with the roll of the boat to starboard in order to release it.

With a final check that nothing surprising was likely to happen, I pulled the split pin out, waited for the tension to come off the wire, and knocked the pin out.

The mast slipped, caught momentarily with a cleat over the guardrail, requiring me to lift it slightly, then slid slowly over the side and disappeared into the depth of the North Atlantic.

It was time for a cup of tea and a think.

I was about 500 miles from Halifax in Nova Scotia and 1,500 miles from both home and my intended destination of Newport where four of us, who had had the OSTAR cancelled at the last minute, were heading in the NOSTAR using the same course and date as the original event.

I had in fact noted crossing the halfway distance only around an hour before losing the mast.

Hasty retreat

The sensible course of action seemed to be to sail home. This would be downwind, with the North Atlantic drift and would be most convenient for repairs.

After tea this plan still seemed to be the best. There was a gale forecast for the evening; it was now 1445 ship’s time and the sea and wind were building.

It would be foolish to make a jury rig until the gale had passed through.

I wondered if we’d manage downwind in the conditions without any sail, so disconnected the tiller from the self steering and pulled it up, holding it strongly as the rolling applied forces on the rudder.

The boom rigged as the new mast. The vertical oars helped align it prior to hoisting. Credit: Jock Hamilton

Little happened initially, then the bow inched around and once it had moved some degrees downwind we started to move ahead.

Once moving she turned downwind, I steered for a few minutes to get a feel and we were soon up to three knots so I reconnected the vane self steering and went below.

I then spoke with my sister and Graham, a friend ashore posting blogs on my behalf at www.beaglecruises.com – my Iridium aerial was on the pushpit.

I reassured them that I was fine and that Freya had no damage other than one stanchion broken. I had loads of food, fuel, water and gas.

I considered whether I was being foolish not asking for help. But even with hindsight, I am convinced this would have been the wrong option; getting off Freya , particularly in poor weather would be dangerous and it would be excruciating to have Freya turn up off the west coast of Europe some time later.

Scuttling her would involve getting safely within reach of help and then opening a seacock .

However the idea of getting nicely alongside a big ship – the likeliest scenario – and hoping that we’d sit there happily whilst going below to open a seacock seemed optimistic.

Conditions would make it dangerous for a ship to launch a rescue boat, and having put myself in danger I had no wish to endanger anyone else.

Some 36 hours passed, making three to six knots downwind in a gale with some impressive seas.

My fellow voyager, Ertan Beskardes , on his Rustler 36 Lazy Otter , was knocked down three times and his windvane steering was washed away.

Two days after the mast loss I tried making a jury rig using a Laser mast and sail I’d brought in case it came in handy.

Up on deck I heard the VHF radio come to life, knowing from my satellite comms that Ertan was close, I went below and we had a chat.

He was heading for the Azores for repairs and only a few miles away. Getting aboard him might have been an option but being a bit gung ho I was optimistic about making it home.

Dismasted offshore: Mast foot arrangement on the jury rig. Credit: Jock Hamilton

It was great to speak to each other despite the inauspicious circumstances. Signing off I continued with the Laser mast.

It was easy to secure the lower half of the mast on deck but trying to do the same with the whole mast and sail proved tricky.

It was apparent that the old dinghy sail was not going to manage a journey of the length anticipated.

I needed a mast to which substantial sails could be added or removed as conditions warranted. This meant rigging the boom or spinnaker boom as a mast.

Continues below…

Crash Test Boat – Dismasted

Extra photographs from Yachting Monthly’s unique series of disasters on our crash test boat, this time it’s Dismasting

“We watched as the mast and sails fell into the water”

Alejandro Perez describes the moment when ARC yacht Garuda was dismasted 600 miles from land

Lessons learned from abandoning ship mid Atlantic

Solo skipper Billy Brannan lost his home when his 34ft yacht Helena was knocked down, rolled and dismasted during an…

Why you should regularly check your deck fittings

What’s really going on under your deck fittings? Ben Sutcliffe-Davies investigates the hidden weaknesses

As the boom was more substantial and had several useful fittings I opted for this, even though it was shorter.

I lashed the dinghy oars vertically, either side of the sprayhood, to keep the boom on the sprayhood so that, before hoisting, it had some angle to the horizontal.

I attached rope shrouds via a convenient hole in the end fitting on a bight. I have holes in my toerail but because they are quite sharp I added large galvanised shackles to these (from my drogue ) to reduce wear.

As my intention was to eventually have a gunter-style rig, I split the backstay to allow the sail to sit in the angle between the two backstays.

The backstays proved too much for the convenient hole so I put a clove hitch around the mast, above three sliders that I’d moved to the ‘mast’ head to hold a block for the headsail – the top one for the block, the other two to help hold it in position – with an end coming down either side.

Having rigged the shrouds and backstays to what I guessed to be the correct length, I clipped on and pulled on the headsail halyard rigged from the bow roller through the head block to my hands whilst holding the ‘mast’ foot on the deck fitting with my foot.

The tri-sail rigged upside down as a jib. Credit: Jock Hamilton

The mast came up to about 40º, which was fine, but there was quite a force on the halyard still and I needed to secure it. As I moved forward, the safety line came tight and I had to stop.

Pulling hard on the lanyard and wiggling around I just about managed to get a couple of turns onto the windlass before shuffling aft again.

I slackened off the backstays, tightened the halyard and repeated this until the ‘mast’ was vertical.

The gooseneck fitting went over a vertical plate on my deck step and was held in place by bolts and spacers to stop it slipping forward or aft.

I’d attached a forestay via a shackle in the convenient hole on the boom, on a bight, so with this and the shrouds tightened, I now had a mast!

The bights on the shrouds proved impossible to ‘refresh’ without dropping the mast, but the forestay worked well.

Sailing home

Calculations suggested my storm tri-sail would fit between the bow roller and masthead so I hoisted it.

Unfortunately the clew sat soggily on the deck because of the low angle of the new forestay.

However, hoisting it upside down proved successful and worked well downwind after testing it out with sheeting points.

A couple of days later, with the wind more on the beam, I pop-riveted a couple of eyelets to half of the Laser mast, lashed the storm jib to this and hoisted it as a main sail, gunter-rig style, which worked fine but blanked the headsail downwind.

With this rig I could sail much like a square rigger; she sat happily from 70º to the apparent wind and I had to ditch one of the sails above 130º or so apparent.

Initially I doused the mainsail downwind but soon learned that it was easier and more efficient to douse the headsail.

This is how I sailed home. I was very lucky in that the wind was mostly favourable, and I was mostly heading straight home.

We averaged 80 miles per day with a maximum of 109 miles.

This was not dissimilar to my mileage made good outbound – our day runs had been better but not always in the right direction.

Jock Hamilton, son of The Restless Wind author Peter Hamilton, has spent most of his life at sea in the Merchant Navy where he currently works as a captain on anchor- handling supply ships. He had a few years working as a bush pilot in southern Africa and did some time with the Royal Marines as a reservist. He is a keen yachtsman and sailed around the world as captain on Blue Leopard . He is intending to spend future summers showing holidaymakers some of the delights of the West of Scotland through Beagle Cruises, using his new yacht Yemaya , a Bowman 49.

I had to stitch up the headsail a couple of times due to wear along the foot – previously the leech – although I never identified why the wear was occurring, it always appeared to be clear of the pulpit.

With no proper mast the motion became very fast, with a roll period of around three seconds.

This was very uncomfortable and generated fast cyclic loads on the rudder whose bearings I worried about without managing to think of a way to alleviate the stresses.

The stove moved so quickly it kept blowing itself out.

I never walked on deck once the mast was down owing to the motion, although I did occasionally stand whilst hanging onto the mast or shroud.

After the first couple of days, as I was already under storm canvas and sailing downwind, I actually had a more relaxing time than I’d had sailing with a full rig upwind and banging into the sea.

Upwind, green water washed over the decks too, with some inevitably finding its way down below despite blanked vents.

I read and played with recipes sent from Hungary and amused myself baking bread; I’d not found the time for these activities on the way out.

NOSTAR casualties

Of the four of us who set off only one made it to Newport and all sustained damage. I wouldn’t say conditions were particularly bad, more unpleasant, and the constant wear and banging whilst going upwind was going to find and exploit any weakness.

The fitting that failed was an eye bolt; whilst sailing home I was kicking myself for not checking it prior to departure.

Once secure on my home mooring, I withdrew it. It had broken clean across with no sign of corrosion , so I don’t believe a visual inspection would have helped.

The voyage home took 18 days and I received a big welcome with a flotilla of boats and a pier lined with friends waving flags.

It was really touching.

Dismasted Offshore: Lessons Learned

- Check all fittings: This may be difficult – withdrawing deck fittings – but will give peace of mind.

- Salvage: It would have been simple to release the rig without saving the boom and, at the time, I didn’t think I needed it for my jury rig, but it later proved invaluable. Anything saved may be useful if you are dismasted offshore but also won’t need replacing; new stuff is very expensive.

- Careful communications: I emailed my boat insurance company and mentioned the transatlantic race. Whether we were officially racing, with no committee, Notice of Race, handicapping agreement, start sequence and so on, may have been moot, however they took this as proof and reduced the claim accordingly. Also consider what people ashore may do; I stipulated I did not need assistance and didn’t want the Coastguard alerted.

- Adapt: I optimistically thought that taking a dinghy mast and sail would be enough to get me home if I was dismasted offshore. I had to adapt my plans after thought and ideas from friends ashore to create a rig to which substantial sails could be added or removed as conditions warranted.

- Plan: Consider the worst-case scenarios. Having things that ‘might come in handy’ was a great help. I lost the windvane from my self steering early on; having a spare was invaluable.

- Replacement cost: Replacing the mast, furler, sails, rigging , radar, wind instrument, lights, winches , cleats and ropes adds up quickly. I had my rig and sails insured for £15,000 whilst replacement cost, new, is more than double that. Insuring a boat for what she cost second-hand may not be realistic.

- Advice from my Father: In my father’s book The Restless Wind , he states: ‘remember the strength of your rig is the strength of the weakest bit of it. Though it’s very heroic to bring your boat in safely after she has been dismasted or half wrecked, it is far more pleasant when she hasn’t.’

Enjoyed reading Dismasted offshore: how one man got his boat home?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

- Inshore Fishing

- Offshore Fishing

- Download ALL AT SEA

- Subscribe to All At Sea

- Advertising – All At Sea – Caribbean

You know you want it...

Mocka Jumbies and Rum...

In the final installment I look at what to do when the rig fails when you are far at sea and on your own.

Broken Shrouds

In 1999, en route to Tortola from the Chesapeake Bay, a new 50ft Gran Soleil that my father was helping deliver from the Annapolis Boat Show, leapt off a wave and snapped her starboard upper shroud with a calamitous BANG! There were three people on board – my father, his friend, and the yacht’s captain. They immediately slammed the boat onto the opposite tack, taking the strain off the broken rigging and narrowly keeping the mast aloft.

“It was like a piece of spaghetti,” my father says, recalling the event.

About 300 nautical miles south of Bermuda, the skipper went aloft with a spare length of rope and lashed together a temporary shroud that allowed them to limp back to the island.

The mast on the Gran Soleil was supported by solid rod rigging, which on commissioning was never properly bent around the upper spreader, ultimately causing excess stress and failure. The captain’s quick thinking, clever jury-rig and conservative sailing, saved the day.

Yacht Rigging Part 1 – Design Particulars

Chainplate Failure

During the 2009 Atlantic Rally for Cruisers, the yacht Liberty suffered a broken chainplate on the port aft lower shroud. It proved a more difficult jury rig than the Gran Soleil, with potentially more dire consequences – when it happened; the yacht was mid-Atlantic, with still 1,500 miles to sail.

The crew set about enacting a repair. The toerail was considered, but thought to be too weak, and in any case, the shroud was too short to reach it. Instead they took a spare halyard, and rove it as tightly as possible through the foredeck and midships cleats, using the primary to winch it tight. The shroud was affixed to the line and tensioned. The repair worked, and the yacht made a safe landfall in St. Lucia a few weeks later.

An even cleverer solution is to replace the actual chainplate. The same piece of Dyneema (see sidebar) that can be used to lash down a jury shroud, can be used to make a loop, which, with some thinking, can be affixed to a bulkhead below decks and led through the hole in the deck where the broken chainplate had been, creating a stronger attachment point.

Yacht Rigging Part 2 – Inspection for Ocean Sailing

Too often the initial reaction after a dismasting is to cut away the spar as quickly as possible for fear of punching a hole in the boat. Evaluate the situation first – that broken spar can be your best hope for a jury-rig, if it is not imminently threatening the hull. Instead, figure out how to get it safely back aboard and save as much of it as possible.

Yves Gelinas, a French single-hander, known for inventing the Cape Horn self-steering system, saved the rig from his Alberg 30 Jean-du-Sud after he was capsized and dismasted northwest of Cape Horn. He limped to Chatham Island (near New Zealand) under jury-rig and spent months repairing his mast from the scraps he saved. Later, he carried on round the world. If you do lose the mast, experiment. Stepping a spinnaker pole and setting small sails upside down can get you safely to port.

It’s impossible to describe the myriad scenarios involving rig failure at sea. The (hopefully) obvious point of this series is to avoid that kind of failure in the first place. Anything can happen at sea, and usually in the blink of an eye – do not panic. Stay calm, discuss the situation and brainstorm a list of solutions before attempting one.

Today’s technology has made it easier for repairing a broken shroud at sea. A length of Dynex Dux (a type of treated SK-75 braided rope), pre-spliced at one end and kept stowed below decks offers a near-permanent solution (my yawl Arcturus is rigged completely with the stuff). Attach the upper eye to the mast tang, lead the shroud down and around the spreader tips (careful to prevent chafe with a piece of rubber hose), Brummel-splice the bottom end a foot short of the chainplate, and use regular Dyneema rope to lash it down to a bow shackle affixed to the chainplate like a toggle.

How to Install a New Trampoline on Your Multihull – Fix the Bad Installs!

Don't Miss a Beat!

Stay in the loop with the Caribbean

- Tips and Tricks

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Culebra Island Guide: Top 10 Must-Visit Spots for a Caribbean Escape

Uncovering the gems of st. martin and st. barts: a top 10 chronicle, miss pfaff rocks: the unlikely companion of our cruising voyage on s&s 41 sy pitufa, so caribbean you can almost taste the rum....

Recent Posts

Powerhouse partnership: dream yacht charter and paradise yacht management join forces, vibe sets sail: a first-look at the caribbean’s boutique boat show experience, rum mates: navigating the world of rum for every palate, recent comments, subscribe to all at sea.

Don't worry... We ain't getting hitched...

EDITOR PICKS

Talkative posts, the seven words you can’t put in a boat name, saying “no”, program for financing older boats – tips and suggestions, popular category.

- Cruise 1742

- St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands 514

- Tortola, British Virgin Islands 432

- Caribbean 424

In maritime transport terms, and most commonly in sailing , jury-rigged [1] is an adjective , a noun , and a verb . It can describe the actions of temporary makeshift running repairs made with only the tools and materials on board; and the subsequent results thereof. The origin of jury-rigged and jury-rigging lies in such efforts done on boats and ships , characteristically sail powered to begin with. Jury-rigging can be applied to any part of a ship; be it its super-structure ( hull , decks ), propulsion systems ( mast , sails , rigging , engine , transmission , propeller ), or controls ( helm , rudder , centreboard , daggerboards , rigging ).

Similar terms

Further reading, external links.

Similarly, after a dismasting , a replacement mast , often referred to as a jury mast [2] (and if necessary, yard ) would be fashioned, and stayed to allow a watercraft to resume making way .

The phrase 'jury-rigged' has been in use since at least 1788. [2] The adjectival use of 'jury', in the sense of makeshift or temporary, has been said to date from at least 1616, when according to the 1933 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of the English Language , it appeared in John Smith 's A Description of New England . [2] It appeared in Smith's more extensive The General History of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles published in 1624. [3]

Two theories about the origin of this usage of 'jury-rig' are:

- A corruption of jury mast; i.e., a mast for the day, a temporary mast, being a spare used when the mast has been carried away. From French jour : 'a day'. [4]

- From the Latin adjutare : 'to aid'; via Old French ajurie : 'help' or 'relief'. [5]

Depending on its size and purpose, a sail-powered boat may carry a limited amount of repair materials, from which some form of jury-rig can be fashioned. Additionally, anything salvageable, such as a spar or spinnaker pole , could be adapted to carrying a form of makeshift sail .

Ships typically carried a selection of spare parts, e.g., items such as topmasts . However, due to their much larger size, at up to 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) in diameter, the lower masts were too large to carry as spares. Example jury-rig configurations include:

- A spare topmast

- The main boom of a brig

- Replacing the foremast with the mizzenmast (mentioned in William N. Brady 's The Kedge Anchor, or Young Sailors' Assistant , 1852)

- The bowsprit set upright and tied to the stump of the original mast.

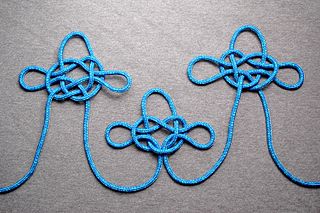

The jury mast knot may provide anchor points for securing makeshift stays and shrouds to support a jury mast, although there is differing evidence of the knot's actual historical use. [6] [7] [8]

Jury-rigs are not limited to boats designed for sail propulsion. Any form of watercraft found without power can be adapted to carry jury sail as necessary. In addition, other essential components of a boat or ship, such as a rudder or tiller , can be said to be 'jury-rigged' when a repair is improvised out of materials at hand. [1]

- The compound word jerry-built , a similar but distinct term, referring to things 'built unsubstantially of bad materials', has a separate origin from jury-rigged . The exact etymology is unknown, but it is probably linked to earlier pejorative uses of the word jerry , attested as early as 1721, and may have been influenced by jury-rigged . [9] [10] [11] The blended terms jerry rigging and jerry-rigged are also common. [12]

- The American terms Afro engineering (short for African engineering ) [13] or nigger -rigging [14] describes a fix that is temporary, done quickly, technically improperly, or without attention to or care for detail. It can also describe shoddy, second-rate workmanship, with whatever materials happen to be available. [15] Nigger-rigging originated in the 1950s United States; [13] the term was euphemized as afro engineering in the 1970s [14] [16] and later again as ghetto rigging . The terms have been used in the U.S. auto mechanic industry to describe quick makeshift repairs. [17] These phrases have largely fallen out of common usage due to their colloquial nature, but are occasionally used within the African-American community. [18] [19] [20] [21]

- Another American expression is redneck technology . [22]

- To MacGyver (or MacGyverize ) something is to rig up something in a hurry using materials at hand, from the title character of the American television show of the same name, who specialized in such improvisation stunts. [23]

- In New Zealand, having a Number 8 wire mentality means to have the ability to make or repair something using any materials at hand, such as standard farm fencing wire. [24]

- In British slang, bodge and bodging refer to doing a job serviceably but inelegantly using whatever tools and materials are at hand; the term derives from bodging , for expedient woodturning using unseasoned, green wood (especially branches recently removed from a nearby tree).

- The chiefly American term do-it-yourself ( DIY ) relatedly refers to creating, repairing, or modifying things without professional or expert assistance.

- Similar concepts in other languages include: jugaad in Hindi and jugaar in Urdu, urawaza ( 裏技 ) in Japanese, tapullo in Genoese dialect , tǔ fǎ ( 土法 ) in Chinese, Trick 17 in German, desenrascar in Portuguese an gambiarra in Brazilian Portuguese , système D in French, jua kali in Swahili . Several equivalent terms in South Africa are n boer maak 'n plan in Afrikaans , izenzele in Zulu , iketsetse in Sotho , and itirele in Tswana . [25]

- Sailing ship accidents

- Bricolage – visual-arts creations from whatever happens to be available

- Chindōgu , a Japanese term for deliberately "un-useful" inventions, created as a hobby and entertainment.

- Exaptation – a shift in the function of a trait during evolution

- Rube Goldberg machine – a complicated, impractical device for performing a very simple task, named for a cartoonist who drew many of them

- Gung ho , a technique of guerilla industry employed at the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives in WWII

- Jugaad – a Hindi word for adopting innovative or simple fixes that may bend certain rules

- Kludge – inelegant solutions that are difficult to maintain

- MacGyver in popular culture § MacGyverisms and "to MacGyver" – terms derived from a TV character who was an inventive jury-rigger

- Repurposing – use of an item (alone or combined with others) for a purpose other than its original function

- Robinsonade – a literary genre named after the novel Robinson Crusoe

- Tofu-dreg project – a phrase used in Mainland China to describe a poorly constructed building

- Upcycling – the transformation of waste into something usable for environmental preservation

- W. Heath Robinson – a British artist known for drawing complicated machines used for simple purposes

- Kitbashing – making a new scale model using pieces taken from multiple different kits

Related Research Articles

A kludge or kluge is a workaround or quick-and-dirty solution that is clumsy, inelegant, inefficient, difficult to extend, and hard to maintain. This term is used in diverse fields such as computer science, aerospace engineering, Internet slang, evolutionary neuroscience, and government. It is similar in meaning to the naval term jury rig .

Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support and control a sailing ship or sail boat's masts and sails. Standing rigging is the fixed rigging that supports masts including shrouds and stays. Running rigging is rigging which adjusts the position of the vessel's sails and spars including halyards, braces, sheets and vangs.

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

A sailing vessel's rig is its arrangement of masts, sails and rigging. Examples include a schooner rig, cutter rig, junk rig, etc. A rig may be broadly categorized as "fore-and-aft", "square", or a combination of both. Within the fore-and-aft category there is a variety of triangular and quadrilateral sail shapes. Spars or battens may be used to help shape a given kind of sail. Each rig may be described with a sail plan—formally, a drawing of a vessel, viewed from the side.

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail. The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

A jib is a triangular sail that sets ahead of the foremast of a sailing vessel. Its tack is fixed to the bowsprit, to the bows, or to the deck between the bowsprit and the foremost mast. Jibs and spinnakers are the two main types of headsails on a modern boat.

In sailing, a halyard or halliard is a line (rope) that is used to hoist a ladder, sail, flag or yard. The term "halyard" derives from the Middle English halier , with the last syllable altered by association with the English unit of measure "yard". Halyards, like most other parts of the running rigging, were classically made of natural fibre like manila or hemp.

A barquentine or schooner barque is a sailing vessel with three or more masts; with a square rigged foremast and fore-and-aft rigged main, mizzen and any other masts.

Running rigging is the rigging of a sailing vessel that is used for raising, lowering, shaping and controlling the sails on a sailing vessel—as opposed to the standing rigging, which supports the mast and bowsprit. Running rigging varies between vessels that are rigged fore and aft and those that are square-rigged.

A spar is a pole of wood, metal or lightweight materials such as carbon fibre used in the rigging of a sailing vessel to carry or support its sail. These include yards, booms, and masts, which serve both to deploy sail and resist compressive and bending forces, as well as the bowsprit and spinnaker pole.

A yard is a spar on a mast from which sails are set. It may be constructed of timber or steel or from more modern materials such as aluminium or carbon fibre. Although some types of fore and aft rigs have yards, the term is usually used to describe the horizontal spars used on square rigged sails. In addition, for some decades after square sails were generally dispensed with, some yards were retained for deploying wireless (radio) aerials and signal flags.

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water. Some remain current, while many date from the 17th to 19th centuries. The word nautical derives from the Latin nauticus , from Greek nautikos , from nautēs : "sailor", from naus : "ship".

Square rig is a generic type of sail and rigging arrangement in which the primary driving sails are carried on horizontal spars which are perpendicular, or square , to the keel of the vessel and to the masts. These spars are called yards and their tips, outside the lifts, are called the yardarms. A ship mainly rigged so is called a square-rigger.

A full-rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel with a sail plan of three or more masts, all of them square-rigged. Such a vessel is said to have a ship rig or be ship-rigged , with each mast stepped in three segments: lower, top, and topgallant.

Rigging may refer to:

The junk rig , also known as the Chinese lugsail , Chinese balanced lug sail , or sampan rig , is a type of sail rig in which rigid members, called battens, span the full width of the sail and extend the sail forward of the mast.

The jury mast knot is traditionally presented as to be used for jury rigging a temporary mast on a sailboat or ship after the original one has been lost; some authors claim a use for derrick poles --but there is no good evidence for actual use. The knot is placed at the top of a new mast with the mast projecting through the center of the knot. The loops of the knot are then used as anchor points for makeshift stays and shrouds. Usually small blocks of wood are affixed to, or a groove cut in, the new mast to prevent the knot from sliding downwards.

Dismasting , also spelled demasting , occurs to a sailing ship when one or more of the masts responsible for hoisting the sails that propel the vessel breaks. Dismasting usually occurs as the result of high winds during a storm acting upon masts, sails, rigging, and spars. Over compression of the mast owing to tightening the rigger too much and g-forces as a consequence of wave action and the boat swinging back and forth can also result in a dismasting. Dismasting does not necessarily impair the vessel's ability to stay afloat, but rather its ability to move under sail power. Frequently, the hull of the vessel remains intact, upright and seaworthy.

A bolt rope , is the rope that is sewn at the edges of the sail to reinforce them, or to fix the sail into a groove in the boom or in the mast.

- 1 2 3 The Oxford English Dictionary, Volume V, H-K . Oxford: Clarendon Press . 1933. p. 637, corrected reprinting 1966.

- ↑ Smith, Captaine Iohn. The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles . London: Michael Sparkes. , (2006, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) digital republication), p.223. ( Online edition ) Note that in the orthography of Early Modern English , 'J' was often written as 'I', thus the actual quote from Smith (1624) reads, "...we had re-accommodated a Iury-mast to returne for Plimoth...", corrected for modern parlance, "...we had re-accommodated a Jury-mast to return for Plymouth..."

- ↑ E. Cobham Brewer 1810–1897. Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. 1898.

- ↑ Barnhart, Robert K., ed. (1988). Barnhart dictionary of etymology . New York : H. W. Wilson Company . p. 560.

- ↑ Hamel, Charles (August 2006) [September 2005]. "Investigations – nœud de capelage or jury rig knot" . Charles.Hamel.free.fr . Charles Hamel . Retrieved 26 January 2022 .

- ↑ Hamel, Charles (August 2006) [September 2005]. "Jury rig investigation – nœud de capelage jury rig mast knot is it only ornamental or utilitarian (with secondary evolution to ornamental)?" . Charles.Hamel.free.fr . Charles Hamel . Retrieved 26 January 2022 .

- ↑ Hamel, Charles (August 2006) [September 2005]. "Jury rig investigation 2 – nœud de capelage jury rig mast knot is it only ornamental or utilitarian (with secondary evolution to ornamental)?" . Charles.Hamel.free.fr . Charles Hamel . Retrieved 26 January 2022 .

- ↑ Israel, Mark (29 September 1997). "jerry-built" / "jury-rigged" . www.Yaelf.com . alt.usage.english Word Origins FAQ. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013 . Retrieved 28 February 2013 .

- ↑ William Morris; Mary Morris (1988). Morris Dictionary of Words and Phrase Origins, 2nd Edition . New York: HarperCollins . pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Wilton, Dave. "jerry-built / jury rig" . www.WordOrigins.org . Word Origins.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016 . Retrieved 28 February 2013 .

- ↑ " 'Jury-rigged' vs. 'jerry-rigged' " . Dictionary.com . 2017 . Retrieved 20 December 2023 .

- 1 2 Green, Jonathan (2005). Cassell's Dictionary of Slang (2 ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson . p. 10, African engineering. ISBN 978-0-304-36636-1 – via Google Books .

- 1 2 Green, Jonathan (2005). Cassell's Dictionary of Slang (2 ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson . p. 1003, nigger rig n.; nigger rig v.; nigger rigged. ISBN 978-0-304-36636-1 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Partridge, Eric (2006). The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English: J-Z . Taylor & Francis . p. 1370, nigger-rig. ISBN 978-0-415-25938-5 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Jackson, Shirley A. (2015). Routledge International Handbook of Race, Class, and Gender . Routledge . Intersections of discourse: Racetalk and class talk. ISBN 978-0-415-63271-3 – via Google Books. 'I can't even nigger-rig it.' ... 'The proper terminology is Afro-engineering.' Here, blackness is demarcated in a classed way. 'Nigger-rigging' is a quick, temporary fix to a problem, but it is a solution that is second rate to the 'right' way. ... declares that this type of knowledge is racialized and classed in a way that deems it inherently inferior. ... implies that black ingenuity and innovation as sub-par and second rate to white ingenuity and innovation. ... By responding indirectly ... consents to this classed usage of the word 'nigger'. Not only does this trivialize whether the slur's usage is inappropriate in the first place, but it equates 'nigger-rigging' with 'Afro-engineering'. ... denotes these terms as synonymous, thus imposing an even more classed meaning to this racial slur.

- ↑ Poteet, Jim; Poteet, Lewis (1992). Car & Motorcycle Slang . toExcel an imprint of iUniverse.com Inc. p. 14, Afro engineering. ISBN 978-0-595-01080-6 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Eisiminger, Sterling K. (1991). The Consequence of Error and Other Language Essays . P. Lang. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-82041-472-0 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Eisiminger, Sterling (1979). Aman, Reinhold (ed.). "A Glossary of Ethnic Slurs in American English". Maledicta . Maledicta Press. 3 (2): 167. Afro engineering

- ↑ Green, Jonathon (1996). Words Apart: The Language of Prejudice . Kyle Cathie . pp. 59 . ISBN 978-1-85626-216-3 .

- ↑ Droney, Damien (2014). "Ironies of Laboratory Work during Ghana's Second Age of Optimism" . Cultural Anthropology . 29 (2). p. 363–384, Ironic Africa. doi : 10.14506/ca29.2.10 .

- ↑ See, e.g.: Kelly, Kevin (2 August 2006). "Street Use: Redneck Technology" . KK.org . Retrieved 20 December 2023 .

- ↑ Rich, John (2006). Warm Up the Snake: a Hollywood Memoir . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press . p. 167. ISBN 9780472115785 . OCLC 67240539 .

- ↑ "Time to 'break free' of No 8 wire mentality" . www.Stuff.co.nz . New Zealand: Stuff. 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Campbell, Angus Donald (2017). "Lay Designers: Grassroots Innovation for Appropriate Change" (PDF) . Massachusetts Institute of Technology – via AngusDonaldCampbell.com.

- Harland, John (1984). Seamanship in the Age of Sail . Naval Institute Press .

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

The Boat Galley

making boat life better

🎧 Jury-Rig Your Rigging

Published on October 14, 2018 ; last updated on December 13, 2023 by Lin Pardey

You are five days out of Bermuda. A shroud breaks, your mast threatens to come down. Few cruisers can imagine a worse scenario. Join Lin Pardey as she relates how two different cruising crews faced this exact situation and came up with jury-rigging that let them sail their boats onward without calling for outside assistance.

Prefer to read? Transcript below.

During the past two months two young couples have told us about the unexpected mast problems that almost ended their cruises. In each case they had rigging failures while they were far from land. In each case they used their ingenuity and gear on board to stabilize the situation and sail onward without calling for assistance. Good on them, the lessons they learned should be added to your –Just-in-case-Jury-rig plans.

Thomas and Claire Khyn are two young French sailors (27 and 29) who stopped in here at Kawau just a day after we arrived home. They arrived here in North Cove, New Zealand last week and have have been cruising for about 16 months since leaving Britanny. Their boat is an older Gib Sea 38 named Schnaps . Soon after they left the Gulf of Panama bound for Easter Island, they noticed the swage fittings on their lower shrouds were beginning to fracture. They had been keeping a careful eye on these swages because as Thomas said, “we inspected them every way we could but we could never see what was actually happening inside those fittings.” [1] Now they watched first one, then the other break as the boat worked through the constant swell they met. They rigged spare halyards to support the mast, they set up all the spare line they had as shrouds. But the stretch in the line let the mast bend far more than they felt was safe. Then they got a new idea. Thomas went aloft and rigged a bridle where the lower shrouds attached to the mast. He then took each end of an eight-meter long piece of chain aloft and secured it as temporary shrouds, using block and tackle at the lower ends to tighten it in place. Since the chain had no stretch and the short length of line used as block and tackle had little stretch, the mast stayed true while they sailed onward to the Gambier Islands. Once there they were able to order mechanical end fittings from Papeete, Tahiti, and wire to replace the broken shrouds. ( Read more about these two sailors and a less frequently visited cruising destination.)

Ky and Hannah Heinze had just sailed past Bermuda, headed for the Mediterranean on board Beatrice , their Cape Dory 30 when the headstay fitting broke. They lashed their forestay to the bowsprit with a block and tackle and started beating back to Bermuda using just the staysail and main. Unfortunately, the windward lowers broke just above the Norseman fittings and brought the whole mast down. They worked for hours getting all the gear free and on board along with both parts of the severed mast. They then were able to set the upper portion in place as a very abbreviated mast. It is what they did to create a jury-rig mainsail that really impressed us. They tied two reefs into the foot of the mainsail, attached slides to it that they had removed from the luff, fitted them into the mast groove, and raised the modified foot as the new luff. With a combination of two hank-on staysails they were able to beat back to Bermuda. Even though it took them two days to jury rig the boat and nine days to beat back, they felt a real sense of accomplishment. Hats off to this intrepid couple who, after a long stay in Bermuda during which they re-rigged their boat, went on to cruise for another six months in the Caribbean before returning to the US so Ky could get his doctorate. One day, they hope to sail to the Med where Ky wants to do further research using his boat as a base while he visits the ancient sites of early Christianity.

We are a bit concerned about the number of rigging failures we are hearing about over the last few years. If you read Webb Chiles account of his latest sailing in the July issue of Cruising World you see he mentions five different wire failures. Add this to those mentioned in Thomas’s footnote and it makes us wonder if modern riggers are fully aware of the rigors of ocean cruising. Many modern boats have very stiff hulls, cruising sailors tend to load their boats slightly (sometimes a lot) more than the designers expected, modern sails do not stretch at all so all the shock loads are directed onto the shrouds. Mechanical end fittings or swages are the norm and these do not have the flexibility of spliced wire. In our minds, all these factors add up to the need for extra heavy wire for offshore voyaging.

[1] We asked Thomas to check this account and he wrote to explain, “The boat was refitted by a conscientious owner ten years before we bought it, then it sat in the marina without being used or sailed. Though we are not 100% sure of it – the rigging was changed during this refit, so we assume it was about ten years old also. As it had not been stressed during all these years, we thought – and it was our mistake – that we could rely upon it until our arrival in NZ, where we would have changed it anyway. But two crews among our friends who changed all the rigging before leaving Europe also had rigging failures at the same time and place (but only 1 strand and they were close to the islands so it was little worry).

Check out our courses and products

Find this helpful? Share and save:

- Facebook 507

- Pinterest 15

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Each week you’ll get:

• Tips from Carolyn • New articles & podcasts • Popular articles you may have missed • Totally FREE – one email a week

SUBSCRIBE NOW

- Questions? Click to Email Me

- Visit Our Store

- MarketPlace

- Digital Archives

- Order A Copy

A jury-rigged rudder

Sharon and Vaughn Hampton and their crew, Dan Knierlemen, left the Galápagos on their boat, Reality , a 1982 51-foot Ta-Yang FD-12, bound for the Marquesas. The passage involved 3,100 miles of downwind sailing with winds ranging from 10 to 25 knots and seas from five to 10 feet — typical coconut milk run conditions.

Six hundred and fifty miles into the trip, Sharon noticed that Reality was not holding her course. The autopilot stopped working. After a few attempts to stop and restart the autopilot, Sharon went to investigate the control box and discovered that it was unusually hot. She immediately disengaged the unit and took over the helm. Steering Reality to starboard was fine, but when she attempted to steer the boat to port, the helm was resistant. With little daylight left and concern that the cause for the autopilot overheating was tied to the port helm condition, Sharon and Vaughn decided to heave to for the night and strategize how they would go about diagnosing the problem.

The next day, with plenty of light, 16 knots SSE and eight-foot seas, they methodically investigated the boat’s dual helm setup. They suspected a bad steering cable was the root of the problem. Their tests concluded, however, that both quadrants and cables were fine. This analysis lead them to investigate the lower rudder packing and it was eliminated as a problem.

Vaughn, Sharon and Dan had 2,350 miles ahead of them and their options were to either hand steer Reality during three-hour watches or to use an old Fleming wind vane (which they had affectionately dubbed Peggy). Otherwise, their least desirable option would be to turn around and head back, upwind, to either Panama or Ecuador. After a few hours, with the wind and sea state stable, Peggy the wind vane was in place. After 150 miles, Peggy proved herself and the decision was made to continue to the Marquesas.

Strange noise from rudder

On day 15, sleeping in the aft cabin, Sharon was awakened by an usual noise that Vaughn had also heard on deck. The noise was coming from the rudder shaft. The bolts for the lower rudder packing had sheered off and the Hamptons were concerned about water entering the boat through the stuffing box. Quickly all hands gathered on deck.

Peggy was left to steer while Vaughn and Dan removed the sheered bolts and Sharon searched through their inventory for new bolts. Working through the night, Vaughn had to cut slots in the sheered bolts to back them out and finish the repair. With 300 miles to go, remarkably, the crew’s nerves were intact. Reality made landfall at Anaho Bay, Nuku Hiva. Despite a thorough underwater investigation of the rudder, Sharon and Vaughn continued to be baffled by the problem at the helm. The next day, Reality went into Taahuku Bay, Hiva Oa, where Dan said goodbye and flew home and Sharon and Vaughn checked in to French Polynesia.

For those readers who have not anchored in Taahuku Bay, the anchorage is small, requires both a bow and stern anchor and the swells from the SE quadrant of the bay refract off the cliffs on the northwest side of the bay turning the bay into a washer board. After a week Vaughn and Sharon set sail for Fatu Hiva, the heaven of the Marquesas Islands. However upon entering Hana Vave Bay, Vaughn realized that he had no steerage and miraculously sailed into the bay and immediately dropped anchor.

It was in Fatu Hiva that Vaughn and Sharon finally saw the problem. A crack that started below the lower rudder packing had now spiraled its way just above the lower rudder packing. The washer board effect in Taahuku Bay must have sealed the fate on Reality’s rudder post. The post was severely cracked.

The couple’s despair was temporary, however. The cruising community and the villagers from Fatu Hiva rallied together and over the course of the next week, helped come up with a remarkably clever solution that allowed Sharon and Vaughn to safely sail Reality to Papeete where she would be refitted with a new post and rudder.

Initially a French cruiser offered articles with instructions on how to create drogues that would help steer Reality without a rudder. Vaughn and Sharon settled on two drogues; one made with a tire offered by a villager who was using it as a planter and the other made from a large canvas bag filled with rocks. Sharon sewed the bag from canvas that was in her inventory for Reality’s awnings and the rocks came from Fatu Hiva’s beach. If the drogues were necessary, they would be deployed on 300 feet of 5/8-inch line that Reality had in inventory.

A workable design

Heribert, a German cruiser on Wassabi with civil engineering skills, came over to Reality to help inspect the situation, and after a few hours, returned to Reality with drawings showing how the rudder could be rigged to be controlled from the helm. Between the villagers, the cruising community and Reality’s inventory, a spinnaker pole, blocks, lines, eye bolts, wood and tools were harvested. At least half of the work needed to be done under the waterline so a cruiser from Australia helped Vaughn by keeping him stable in the water while Vaughn applied pressure to drill holes into the rudder. Using a hand-held auger, Vaughn drilled four holes into the rudder and positioned two aluminum backing plates to mount the two eye bolts.

They attached blocks to the ends of the spinnaker pole, which was reinforced by lumber lashed along its length. Lines where then connected from each side of the rudder to its respective side of the pole, through the blocks and onto the helm. This allowed Vaughn or Sharon to steer Reality by pulling one or another of the lines.

Heribert’s design suggestion was to make these control lines a single loop. Then by wrapping this loop around the wheel hub, turning the wheel tightened one line while the opposition line was automatically released, thus turning the rudder.

In addition to various items that were gathered for this jury-rigged steering system, Vaughn and Sharon were able to purchase 50 gallons of fuel from the cruising community. Not knowing how well and how long this system would work with sails, Vaughn and Sharon knew that they would need to motor-sail most of the way back to Papeete, some 850 miles. Despite the additional 50 gallons, they knew they were short on fuel for the route that required they keep a wide berth around the low atolls of the Tuamotus.

After a week of planning and preparing, it was time to see if all the theoretical solutions would actually steer the boat. With the assistance of five dinghies, Sharon and Vaughn weighed anchor. Chaos ensued for the first 10 minutes as the dinghies tried to pull Reality safely out of the anchorage. A last-minute wind shift began blowing Reality back into the anchorage and near the rocky shore. The dingy team was not making headway and Reality was floundering. Vaughn and Sharon realized that the lines controlling the rudder were run the wrong way. Vaughn quickly reversed his steering, Reality cleared the rocks at the mouth of the bay and they were on their way. Once out in open water, Sharon and Vaughn reversed the rudder lines so turning to starboard actually turned Reality to starboard. With Fatu Hiva fading into the distance, Sharon and Vaughn relaxed, gaining confidence with each mile that the jury-rigged steering system was able to steer Reality .

Vaughan and Sharon safely arrived in Papeete on May 5th, sailing 850 miles in eight days without incident. They had been able to sail slowly, approximately 100 miles per day, and still had plenty of fuel in reserve.

A tug assisted their entry into the harbor and after 23 days, Reality had a new rudder and post.

——– Fay Mark, a former high tech marketing executive, is voyaging with her partner, Russ Irwin, on New Morning , their 54-foot Chuck Paine-designed sloop. For more information about Fay, Russ, New Morning, and their cruising adventures, visit www.newmorning.info .

By Ocean Navigator

- Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Dismasted at sea: What to do during and after a dismasting

- September 30, 2019

Losing your mast is one of the worst things that can happen during an ocean crossing – bluewater veteran Susan Glenny explains what to do after a dismasting

When the Hallberg Rassy 46 Lykke dismasted during the 2017 ARC, the spinnaker pole was drafted in as a jury mast to support a light and VHF aerial

During the 2017 Rolex Fastnet Race , my yacht Olympia ’ s Tigress , a Beneteau First 40, lost her rig through a simple split pin failure.

We were 40 miles offshore at the time, with a trained but inexperienced charter crew on board. It was blowing a Force 6 and the middle the night. The following are some of the lessons we learned from the incident.

Just before midnight I went down below after my watch, having just come off the helm. I heard shouting from on deck and the first mate calling: “Sue, get on deck now – the shroud’s gone!”

Olympia’s Tigress setting off in the 2017 Rolex Fastnet Race, before the rig failure. Photo: Carlo Borlenghi

I rushed to get my lifejacket back on and pulled myself up the companionway. Looking out I could see that the V1 rod from the port side of the rig had detached completely at the first spreader. The rod was still attached at the deck chainplate but was arched over and dragging in the water. I turned to the helmsperson and shouted: “Whatever you do, don’t tack.”

We were upwind on starboard tack beating into a moderate to rough seaway, and if you were looking at the rig fully loaded from the starboard side you could have been fooled into thinking all was well.

But this was just the start – it would be ten hours before yacht and crew made it safely to land. For myself and four other crew, who’d just spent a full four hours on watch on deck, this was to be particularly exhausting.

Article continues below…

Running aground: Lessons learned from a nightmare scenario

We hit the sandspit at something over five knots and went hard aground. A moment before, the bottom had risen…

What are the most common repairs at sea for yachts sailing across the Atlantic? ARC survey results tell all

You cannot presume to be able to sail across an ocean without experiencing some problems or breakages with your equipment.…

My first plan was to try to keep the yacht stable under sail as we were closer towards land – and potential rescue – on the starboard tack. I called Falmouth Coastguard from our satellite phone and explained that we had a major rig failure; they contacted the Irish Coast Guard on our behalf. They also advised us to have our EPRIB on deck.

From midnight until around 0130 we sailed on starboard tack to get closer to land, but progressively got knocked and were no longer laying the Irish coast.

We managed to sail about 15 miles further inshore before, as predicted, the wind began to back. Soon we were no longer laying even the Fastnet Rock.

Safe after a lifeboat tow back to port, but Olympia’s Tigress had lost her mast above the first set of spreaders

At this point, around 0200, and two hours after we first noticed the issue with the shroud, I decided we needed to down sails and be prepared for whatever was going to happen to us next.

At first we tried to stabilise the rig using halyards as we motored towards Kinsale, but it quickly became apparent how completely unstable the whole rig was.

The flexibility of the aluminium mast was quite terrifying and in the rolling seaway the top of the mast was swaying up to 3-4m from the centreline. This caused ricocheting of the stabilising halyards from the deck and the noise was deafening, like a huge recoiling spring.

The Class 40 Phor-ty lost her rig during the same race – these aerial shots reveal the dangerous tangle of lines, rigging, sail and mast across the deck and cockpit. Photo: Carlo Borlenghi

I was extremely concerned about having anyone on deck because it was apparent that the rig was eventually going to come down.

Having no windward force on the rig, as you would do when sailing, meant the rig’s movement and which way it would fall was also totally unpredictable.

Thunderbolt crack

I sent all the crew below and slowed the boat speed to 3 knots. We were in contact with the Irish Coast Guard by satellite phone and limited VHF.

The Courtmacsherry lifeboat had been mustered in case the broken spar holed the boat.

At 0420 the yacht rolled violently to port in a big wave and, as we rolled back to starboard, the mast cracked with a sound like a thunderbolt.

It fractured cleanly at the first spreader level and fell to the starboard side, taking out all of the guard wires and damaging the deck.

The standing rigging on the port side was already compromised but the rig remained attached by the starboard V1 rod, the forestay rod and the backstay, which was Dyneema.

What followed was an extremely stressful 25 minutes of cutting the rig away, trying various methods, because you never knew what was going to work until it did.

The crew worked in groups on different parts of the rig, and we had the liferaft prepared to deploy in case the spar ruptured the hull.

The second mate had climbed what remained of the rig to cut the wires from the mast. What I remember most clearly is that absolutely everyone on board was waiting for instruction on what to do next.

The hardest part was the determination required to sever the highly loaded and arched rod rigging. The V1, with the rest of the rig, was moving up and down with the seaway and it felt like a miracle when we managed to saw it off – it was just brute force sawing with a hacksaw that got rid of it.

A hacksaw should deal with a felled forestay – but be aware that rigging under tension can whiplash unpredictably when cut

Next we removed the forestay by unscrewing the bottle screws and lastly freed the backstay.

Five-hour ordeal

At 0445 the rig sank. There was silence on board; no one said a thing for at least a minute. We were all in total and utter shock after a five-hour ordeal.

I first established if everyone was OK. Our youngest crew member had a metal shard in his eye resulting from the flying sparks of an angle grinder, while my second mate had taken a serious blow in the face as he detached the forestay from its fixing; the rod had ricocheted into his face. So we began tending to the injuries.

By 0500 the RNLI lifeboat arrived on the scene. They first checked with us that the rig had sunk, and we communicated with them through visual signalling and limited coms on a handheld VHF radio – the fixed VHF antenna went with the mast.

At this stage we were still 25 miles offshore – we were happy to motor to Kinsale or Cork but the lifeboat crew deemed it better to tow us given our lack of VHF and associated electrics. The stability of the yacht was also severely compromised without the mast.