- News & Views

- Boats & Gear

- Lunacy Report

- Techniques & Tactics

WHARRAM PAHI 42: A Polynesian Catamaran

The catamaran designs that British multihull pioneer James Wharram first created for amateur boatbuilders in the mid-1960s were influenced by the boats he built and voyaged upon during the 1950s. These “Classic” designs, as Wharram termed them, feature slab-sided, double-ended, V-bottomed plywood hulls with very flat sheerlines and simple triangular sections. The hulls are joined together by solid wood beams and crude slat-planked open bridgedecks.

Wharram’s second-generation “Pahi” designs, which he started developing in the mid-1970s, still feature double-ended V-bottomed hulls, but the sections are slightly rounder and the sheerlines rise at either end in dramatically up-swept prows and sterns. The most successful of these in terms of number of boats built–and also probably the most successful of any of Wharram’s larger designs–is the Pahi 42. It is an excellent example of a no-frills do-it-yourself cruising catamaran with enough space for a family to live aboard long term.

First introduced in 1980, the Pahi 42, a.k.a. the “Captain Cook,” was the first Wharram design to include accommodations space on the bridgedeck in the form of a small low-profile pod containing a berth and/or (in some variations) a nav station. Unlike the Classic designs, which have no underwater foils other than rudders, the Pahis also have daggerboards, though these are quite shallow and are set far forward in each hull. The rudders are inboard, rather than transom-hung, set in V-shaped wells behind the aft cross-beam.

As on the Classic designs, the cross-beams are flexibly mounted to the hulls, but are lashed with rope rather than bolted on with large rubber bushings. Hull construction likewise is very simple, all in plywood, and explicitly conceived to facilitate home-building by amateurs. The frames consist of a series of flat bulkhead panels fastened to a long centerline backbone with longitudinal stringers running down either side to support the plywood skin panels. Through the main central area of each hull the bulkheads all have large cutouts in their midsections to allow room for interior accommodations space. To increase moisture and abrasion resistance the hull exteriors are sheathed in fiberglass cloth and epoxy.

As designed the Pahi 42 has a single mast and flies a loose-footed mainsail with a wishbone boom. There is also a staysail on a wishbone boom and a conventional genoa flying on a bridle over the forward beam. Many owner-builders have substituted other rigs, including Wharram’s unique gaff “wingsail” rig, where the main has a luff sleeve enveloping the mast, but conventional Marconi rigs are probably the most common. The original design also calls for a single outboard engine mounted on the stern deck to serve as auxiliary power, but many owners have engineered other arrangements, including inboard diesel engines and even electric drives.

As its light-ship D/L and SA/D ratios attest, the Pahi 42 has the potential to be a very fast performance cruiser. Wharram claims top speeds in the neighborhood of 18 knots with average cruising speeds of 9 to 12 knots. In reality, however, it probably takes an unusually attentive, disciplined sailor to achieve anything like this. The Pahi seems to be more weight sensitive than most cats and typical owners, who carry lots of stuff on their boats, report average speeds more on the order of 5 to 8 knots.

The boat also does not sail well to windward, as its daggerboards are not large enough and are not positioned properly to generate much lift. Instead they act more like trim boards and help balance the helm while sailing. They also make it difficult to tack. Most owner-builders therefore consider the boards more trouble than they’re worth and don’t install them, preferring instead to retain the extra space below for storage and accommodations. With only its V-shaped hulls to resist leeway the Pahi reportedly sails closehauled at a 60 degree angle to the wind, though performance-oriented owners who keep their boats light claim they can make progress upwind faster than other boats sailing tighter angles. A few builders have also put long fin keels on their boats and these reportedly improve windward performance to some extent.

As for its accommodations plan, the Pahi 42 has much in common with other open-bridgedeck catamarans. Except for the small pod on deck all sheltered living space is contained within the narrow hulls, which have a maximum beam of just 6 feet. The standard layout puts double berths at both ends of each hull, though many may regard the aft “doubles” as wide singles. The central part of the port hull contains a small dinette table and a large galley; the center of the starboard hull is given over to a long chart table or work bench, plus a head.

Naturally, many owner-builders have fiddled the design a bit to suit their own tastes. The most significant changes involve the deck pod. Those who crave more living space tend to enlarge it; in at least one case it has blossomed into something approaching a full-on bridgedeck saloon, which must hurt sailing performance. In other instances, in an effort to save weight and improve performance, builders have omitted the pod entirely.

The great advantage of a Pahi 42, or any Wharram cat for that matter, is its relatively low cost compared to other cats in the same size range. To obtain one new, however, you normally must build it yourself. Wharram estimates this takes between 2,500 to 3,000 hours of effort. The alternative is to buy one used, which now normally costs less than building one.

There is an active brokerage market with boats listed for sale all over the world. The best sources for listings are Wharram himself and another Brit, Scott Brown , who operates mostly online. Because Wharrams are built of plywood, even if sheathed with epoxy and glass, the most important defect to look for is simple rot. This, however, is not hard to detect and, because the boats are structurally so simple, is also not hard to repair.

Specifications

Beam: 22’0”

–Boards up: 2’1”

–Boards down: 3’6”

Displacement

–Light ship: 7,840 lbs.

–Maximum load: 14,560 lbs.

–Working sail: 640 sq.ft.

–Maximum sail: 1,000 sq.ft.

Fuel: Variable

Water: Variable

–Light ship: 89

–Maximum load: 165

–Working sail: 25.91 (light ship); 17.14 (max. load)

–Maximum sail: 40.48 (light ship); 26.78 (max. load)

Nominal hull speed

–Light ship: 11.9 knots

–Maximum load: 9.8 knots

Build cost: $70K – $120K

Typical asking prices: $40K – 100K

Related Posts

CRAZY CUSTOM CRUISING BOATS: New Rides for Pete Goss and Barry Spanier

HANSTAIGER X1: The Trimaran To End All Trimarans

please more info and prices for this model!

Response to Goran below: I recommend you follow the link above to Scott Brown’s website. Lots of boats and prices there!

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please enable the javascript to submit this form

Recent Posts

- MAINTENANCE & SUCH: July 4 Maine Coast Mini-Cruz

- SAILGP 2024 NEW YORK: Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

- MAPTATTOO NAV TABLET: Heavy-Duty All-Weather Cockpit Plotter

- DEAD GUY: Bill Butler

- NORTHBOUND LUNACY 2024: The Return of Capt. Cripple—Solo from the Virgins All the Way Home

Recent Comments

- cpt jon on NORTHBOUND LUNACY 2023: Phase Two, in Which I Exit North Carolina via Oregon Inlet

- Sanouch on A PRINCE IN HIS REALM: The Amazing Life of Thomas Thor Tangvald

- Peter Willis on DEAD GUY: Donald M. Street, Jr.

- Charles Doane on SAILGP 2024 NEW YORK: Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

- Pete Hogan on SAILGP 2024 NEW YORK: Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- October 2009

- Boats & Gear

- News & Views

- Techniques & Tactics

- The Lunacy Report

- Uncategorized

- Unsorted comments

Building, restoration, and repair with epoxy

James Wharram Designs

By captain james r. watson —gbi technical advisor.

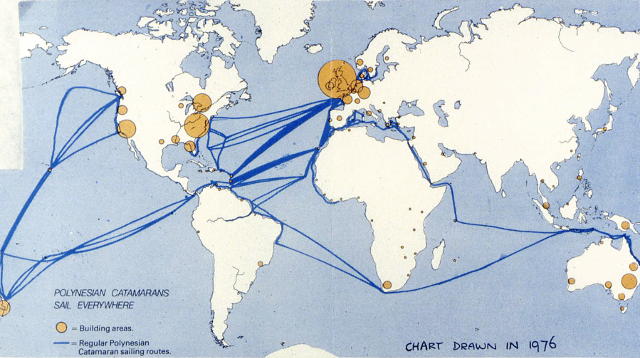

For many decades Gougeon Brothers Inc. has kept in contact with multihull designer James Wharram. Wharram, of Cornwall, UK, has sailed and designed Polynesian-style catamarans for 50 years. Amateurs and professionals have built his boats and sailed them to all corners of the planet. The designs he creates with his engineer and artist partner Hanneke Boon have evolved over the years, but remain unmistakably, Wharram Catamarans.

Wharram boats are sailing, sea-going, cruising catamarans ranging from small day boats to 60′ habitats. Many sailors have undertaken successful voyages in Wharram-designed boats. These particular Wharram catamarans have one thing in common, they were all built with WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy.

These boats are constructed of modern materials:plywood, epoxy and synthetic fibers. The drawings are simple, streamlined and clearly explained resulting in a high boat completion rate among buyers of Wharram plans. This is reassuring to the amateur builder undertaking the “unknown”of building such a craft.

The V-shaped hulls typical of Wharram designs can carry a lot of extra weight without deteriorating sailing performance. The hull structure in most of the designs is a slightly stressed skin bonded with epoxy, fillets and fiberglass tape over a simple plywood/stringer framework. This results in a rigid structure. The hulls are joined to wood/epoxy structural beams via a flexible lashing system originally employed by the ancient seafarers of the Pacific, but with modern synthetic fibers proven reliable and seaworthy. Absence of a deck cabin reduces windage and lowers center of gravity, thereby increasing stability and safety at sea.

The bow of a James Wharram Polynesian-style catamaran, the Tama Moana.

The Tama Moana, a Polynesian-style catamaran designed by James Wharram.

Tahiti Wayfarer is another James Wharram-designed Polynesian-style catamaran.

The Tahiti Wayfarer’s twin catamaran bows.

Detail of James Wharram’s Polynesian-style catamaran.

The Tiki 30 UNN:IA on the water.

The Pahi 63, is another James Wharram-designed Polynesian-style sailing catamaran.

It’s easy to see the scale of the Pahi 63 against these buildings.

Pahi 63 detail.

- Practical Boat Owner

- Digital edition

Nomads of the wind – an article by James Wharram

- January 5, 2022

In light of the recent passing of pioneering multihull designer James Wharram, we share his Practical Boat Owner article from our October 1994 issue, published for the first time online.

To Gran Canaria from Tenerife at 14 to 16 knots

In 1993 James Wharram and his family adopted the life-style of Polynesian migrants on board their double canoe Spirit of Gaia .

They voyaged 6,000 miles, experienced dozens of adventures and discovered why those intrepid pacific explorers worshipped their boats as gods..

An article by James Wharram.

The BBC’s acclaimed series Nomads of the Wind , was the fantastic story of the Polynesian migrations and subsequent island discoveries across thousands of miles of Pacific Ocean aboard sea-going double canoes.

These double canoe raft ships were known to have been developed for offshore sailing 2,000 years ago.

A direct descendant of these craft are the present day catamarans.

Can we compare the sailing ability of the modern catamaran to the ancient double canoe vessels of the Polynesians?

Can we present-day sailors and designers learn anything from one of Man’s great ethnic ship designs of history ?

I think we can.

Where the spirit took them: Spirit of Gaia

Live-aboard lifestyle

In 1993 I lived as a ‘ Nomad of the Wind ‘ aboard our 63ft ethnic proportioned Double Canoe, the Spirit of Gaia .

We made a voyage of 6,000 miles, sailing from landfall to landfall: Falmouth, North Spain, South Portugal, and from island group to island group: the Canaries, the Madeiras, the Baleares (in the Mediterranean), a voyage of many adventures, that stimulated new ideas and gave us insights into the minds of Polynesians.

There was the memorable voyage, 500 miles from Gran Canaria to Funchal on Maderia, when, with the rudders lashed, in light winds, the Double Canoe glided across the ocean.

For a while, we left this century and the western world to become a part of the Polynesian sea world.

Turtles in the sea, dolphins around, sea birds flying in the sunset, and the nights lit with brilliant stars.

We loved our ship.

Poetry of the sea

Throughout history seafaring races have been poetical about their seafaring craft.

But you can only be in love with a ship that returns affection in sailing ability.

It could be the ability to point into the wind, so that you can reach a sheltering bay or harbour that lies upwind; it may be that the sails are easily handled in a squall; its motion may feel like a dance over the waves or it may have the lift and buoyancy to ride out storms.

Maybe it has a sense of power in reserve for that emergency, when you need to push the boat harder without incurring damage to the craft.

Sea-people learn to trust their subjective and instinctive boat feeling, that their craft is in tune with nature.

The Spirit of Gaia is such a ship.

To satisfy the Western analysing part of our nature, we fitted the Spirit of Gaia with Brookes and Gatehouse “Focus” instruments for recording true and apparent wind angles, windspeed and a sensitive log for speed through the water.

In addition we carried a Sony GPS for point position finding.

Some yachting magazines print boat performance in a diagram called a polar curve, which combines three facts: True wind speed, true wind angle and boat speed, but to get a better picture of how the boat sails, you need more information: apparent wind angles, sail area carried related to the stability of the vessel (most important for multihulls) and speed/length ratios to compare the results with other boats.

Hanneke, my design partner, chief mate on the Spirit of Gaia , has drawn the Gaia’s sailing performance in wind force 5-7 (see figure 1) giving all this additional information and, for those interested in the finer points of sailing, the contain much to study.

Spirit of Gaia – sailing performance in open ocean wind force 5-7, waves 5-6ft high, occasionally 10-13ft

The Polynesian ethnic proportioned Spirit of Gaia can sail with her schooner rig 45º off the true wind, can cruise in force 4 (11-16 knots) winds at average speeds of 10 knots, which is a speed/length ratio of almost 1.5√WLL, (WLL being the waterline length) equivalent to the top average which a monohull racer, hard driven over on her ear, can be expected to achieve.

Pushed a little harder, she sails at 14-16 knots, which equals 2.2√WLL.

Note, at this speed her stability of 56 knots!

Many people fear fast catamarans as they are known to capsize.

Festive feel on the helm

The joy of sailing the Spirit of Gaia at an easy 10 knots was best summed up by an Austrian sailor, who, after four hours at the wheel, when offered a relief, declined, saying:

“This is like Christmas all the time.”

To sail with ease, upright and with little structural stress at speeds proportional to the Clipper Ships and hard-driven modern Ocean Racers, in wind strength of only 13-15 knots (force 4) does demonstrate the design genius of the ancient Polynesian Double Canoes.

A student of the pre-European Polynesian Double Canoe designs could point out:

“Your Spirit of Gaia may have Polynesian hull shapes, rounded V hulls and waterline/length ratios of 17:1, but she is different in certain aspects of design from an ethnic Polynesian Double Canoes. “You have improved on the basic concept with modern design concepts, for the Spirit of Gaia has the wide overall beam and the large sail area/displacement ratio of a modern multihull, using advanced sail design with sails made of modern Terylene. “The Polynesian sails were made of ‘matting’.”

This is all true, and, using the hulls of the existing Spirit of Gaia , Hanneke has drawn out a more ethnic Polynesian Double Canoe (see figure 2).

In reverence to the Spirit of Gaia’s Hawaiian name, given to her by her Hawaiian launching crew, who came to Cornwall specifically for the occasion, we will refer to this craft as the Makua Hine Honua .

The author in relaxed mode

Seagoing performance

At first glance, the diagram suggests a very narrow beamed catamaran with peculiar shaped sails of moderate area and a deep paddle for steering and another for leeway prevention.

Can such a craft compare in speed and seagoing ability with a modern performance catamaran?

Let us look in more detail at the possibilities.

The prime factor in design of cruising catamaran speed and sea-going ability is sufficient stability, for without it, you have an upside down catamaran.

The ‘narrow beamed’ (by modern standards) Makua Hine Honua with her low rig has a calculated static stability of 28 knots!

This means, under full sail, it would take a gale of 28 knots to capsize her (though, to allow for wind gusts, ie dynamic stability, it would be advisable to consider reefing at 23 knots of wind).

Many of the wide-beamed, modern, performance, cruising catamarans on the market, to which the Makua Hine Honua is compared, have a static stability as low as 25-27 knots.

This means, if you do not stand by the sheets at wind speeds of force 4 prepared for instant release, in a wind gust, there is a risk of sudden capsize.

Nobody is quite certain why Polynesian Catamarans had, in relation to the modern catamarans, a narrow overall beam, though we can see, that it did not affect stability.

For years I thought it was for greater manoeuvrability when under power (ie paddle power).

Now I am beginning to suspect that the Polynesians were as advanced in hull dynamics as they were in the aerodynamics of sail design.

Perhaps the interacting bow waves, through their narrow hull separation, provide close to the bows a hydro-dynamic lift against pitchpoling – a problem of some modern catamarans.

The sail rig on the Makua Hine Honua does look like the modern Bermudan sail rig set upside down.

C. A. Marchaj, a leading theoretician on aero and fluid dynamics of yacht design, did tunnel testing of Polynesian sail shapes, and found that close hauled at a true wind angle of 40º the Polynesian sail gave 5% less drive than the modern “High Performance” Bermudan mainsail and jib.

However, free the Polynesian sail off to wind angles of 50º-60º on the beam, and this sail shape gives 5-10% more drive than the Bermudan mainsail and jib.

Polynesian know-how

The Polynesian sails of old were made of matting but not the type of matting you may have on your kitchen floor.

Generations of Polynesians had developed a tough, finger-woven “fabric” from finely split tensile Pandanus palm leaves.

It was a most effective windward material.

The rig shown on the Makua Hine Honua with modern theory and experiments in wind tunnels in its favour can be regarded as an efficient, high pointing windward rig.

The original Polynesians lived and sailed in the trade wind areas, where for most of the time winds blow between force 4-7.

The Polynesians did not need large sail areas.

In winds of force 4 upwards, the moderate 800 square feet Polynesian rig of the Makua Hine Honua would power her on a close reach (55º-60º off the wind) between 150-250 miles in a 24 hour period.

So, with light overall weight (we calculated her weight at 7 tons in traditional materials), plus high stability, efficient windward sails mounted on an efficient windward hull form, the Makua Hine Honua of antiquity is, by present day analysis, an efficient sailing machine.

In fact, the oldest, (by 2,000 years), earliest double-hulled craft is a basic point of reference by which to judge subsequent double-hulled sailing craft.

With reference to the Spirit of Gaia , I have written “We loved our ship.”

Well, the Polynesians worshipped theirs.

Article continues below…

Fair winds to pioneering multihull designer James Wharram

Fair winds to free-spirited sailor and pioneering multihull designer James Wharram who passed away on 14 December, at the age

Sailing for All – the 1950s: a short history of yacht design

Although the post-war period was a time of scarcity – food rationing in the UK continued until 1954 – it…

British designer James Wharram’s round-the-world adventure on Spirit of Gaia

The morning breeze was just starting to fill in as we headed out of Port Vathi on board Ionian Spirit,…

‘Go faster’ lines

The double canoe and sailing the oceans was at the heart of their religious beliefs and social customs and attitudes.

According to the early European sailors, the finish and decoration of their ships “was of the highest standards.”

Polynesian hulls were a vivid polished black, red or yellow colour.

They were decorated at bows and sterns by highly elaborate, sacred carvings and had what we might call ‘go faster’ lines – not in paint but glittering inlays of mother of pearl shell, or, in some observed examples, sacred bird feathers, usually coloured red, fixed in a shimmering band around the hulls, just below the gunwales.

Heading upwind, swooping across the tradewind seas, such craft could easily sail distances between 1,500 to 2,000 miles in 10 days.

If they found no new land, they could easily turn around and run with the wind home.

Returning ships like these were described by the early Europeans as riding through the passes in the reefs at high speed towards the beaches.

Streamers from the sails were flying in the wind, people singing, drums beating, conch-shells blowing and naked girls dancing on the high bow and stern platforms.

Mediterranean idyll: anchored on the Costa Brava

For sailing in colder northern latitudes, as we did a western cruising catamaran designer needs to add some creature comforts to the basic Polynesian sailing machine:

For example:

- Weather shelter

- Private toilet facilities

- Private sleeping places with double bunks

- A communal dining table

In the first 25 years of western cruising catamaran development from 1960 to 1985, designers did succeed in developing catamarans with speeds of equal and above the fast monohulls, that provided sufficient weather shelter, western privacy standards, a fixed table with seats around, and most important, a high degree of static stability against capsize, at moderate cost unit.

Around 1985 a new trend in western catamaran development began.

This design trend encompasses the “Modern Performance Catamaran”.

It is hard to remember in the financially stringent 1990s, how the mid-1980s was a time of large amounts of surplus wealth, known as the ‘Yuppy Era’.

The non-heeling, wide beam of the raft-like catamaran provides a superb base for luxurious, spacious accommodation.

In theory, it only needed to join this accommodation to the high speeds of the ocean racing catamaran of the mid-1980s, and you had, for the requirements of the ‘Yuppy era’, an excellent package for marketing purposes.

A cruiser incorporating speed, high-tech and luxury.

Five star luxury

New designers came forward to develop this package.

They looked to computer technology for design inspiration, rather than to nature and man’s sailing history.

The Polynesians, if these people had ever heard of them, had no relevance at all to the modern catamaran design.

With computer-aided design they set out to optimise every aspect of the previous designed western catamaran: freeboard, internal volume, overall beam, mast height, sail area.

This optimised package was then styled, internally to the luxury of a five star hotel suite and externally to car and powerboat styling concepts to imply speed.

How far these new designs diverged in design aspects from the ethnic proportioned catamaran can be seen in the bottom of the graphic.

The shaded catamaran is a composite of five ‘modern performance’ catamarans.

Easily combined, they had remarkably similar freeboard, mast height and sail area proportions.

The modern performance catamaran has everything a modern, wealthy, soft, urban commuter could wish for.

For every two crew members there is an ensuite toilet and shower.

That means four toilets to eight people.

Double beds five feet wide (though I have notices that they often lack the ergonomics for a varied sex life).

They have water desalinators, washing machines, microwave ovens, deep freezers, quality stereos, television, electronic instruments to aeroplane cockpit display standards and so on.

In these aspects, they are certainly ‘modern.’

Spirit of Gaia specifications

Performance values

But how do they measure-up when it comes to performance.

Indeed, what is meant by the word performance ?

It is a very slippery word.

It is a modern advertising word and means different things to people of different attitudes.

To myself and many designers, it is always used together with other words, like performance in relation ‘to’.

The practical proven windward performance of the Spirit of Gaia is 45º off the true wind.

The theoretical windward performance of the ‘High Performance Bermudan Racing Rig’, as used on the composite ‘Modern Performance Catamaran’, is 3-5º closer to the wind, ie 40º off the true wind.

The Spirit of Gaia rig costs £11,000; the shown Bermudan rig was worked out at approximately £50,000.

So, in order to achieve a theoretical ability to sail 5º closer to the wind, you have to spend £40,000 more.

In cost efficiency, the shown Bermudan rig has very poor ‘performance’.

In stability values, the shown Bermudan rig has also poor performance.

The composite ‘Performance Catamaran’ with his high heeling rig, for safety in wind gusts, would need to be reefed at force5, whereas the narrow beamed Double Canoe Makua Hine Honua only needs reefing at force 6. (So does the Spirit of Gaia ).

The high profile (so high, they were last used in sailing ships of the 16th and 17th century) of the composite craft, will reduce windward performance in winds above force 5 to the point where engines become a vital component of the windward performance.

That is the reason, why the manufacturers of modern performance catamarans, always stress the power and quality of their engines when it comes to the hard sell.

(The 63ft Spirit of Gaia has two 9.9hp, four stroke Yamaha outboards).

The Polynesian Double Canoe is a product of evolutionary design logic for a fast craft using the minimum of materials and resources to sail the seas.

The modern performance catamaran is a consumer product which has evolved over a relatively short time period and is suitable only for a limited number of people.

It was mainly due to the high advertising budgets of the late 1980s, that the modern performance catamaran was projected as ‘state of the art’ in the cruising catamaran development.

In the more financially stringent 1990s, the numerical market base of wealthy yacht owners has narrowed considerably.

Can the present day ‘modern’ cruising catamaran concept survive on such a narrow market base?

What the ancient Polynesian Double Canoe designers have sown through the Spirit of Gaia is an opening into a ‘Post Modern’ school of catamaran design, that can move forward in the financially stringent 1990s, using the logical design principles of the Polynesian Double Canoe, improving its lack of accommodation and weather shelter within the constraints of evolutionary developed sailing ship design.

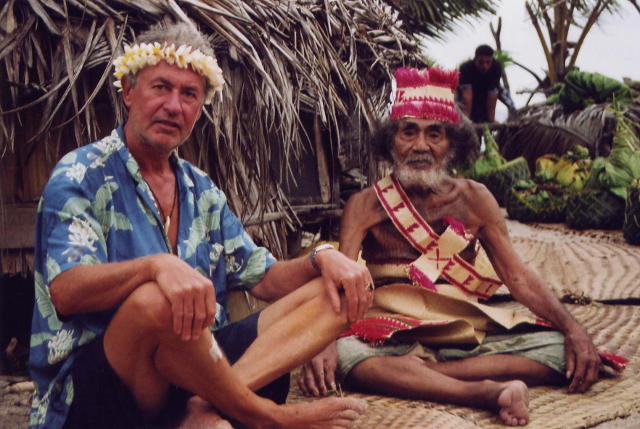

Author James Wharram, pictured in 2004

Conche conscious

It makes sense never to forget: cruising is more than hard efficiency or wealth display.

It is about the joy of sailing and companionship.

I remember a night in a quiet Mallorcan anchorage, sitting on deck, with our mixed crew of Japanese Shige, Canary Islander Sergio, and four exotic Spanish Catalan women, the fire flickering in the central deck fire-pit, stars overhead, the crew began to beat drums, tapping together pieces of fire log and clicking stones into a hypnotic primitive rhythm.

Someone began to blow the conche shell.

From the aft cabin pod, the call was sung into the night: ‘ Makua Hine Honua ‘.

Shige began to dance a primitive Okinawan dance.

Then, one of the Catalan women, dressed only in a sarong, stood up and also began to dance.

Her long hair swinging in a cloud around her, she approached me and drew me into her dance.

By the time you read this article, Shige, the Japanese, Sergio the Canary Islander, Dora, the Catalan, Hanneke, the Dutch, Ruther, the German, my son Jamie and me, the sea-gods willing, will be heading across the ocean on Spirit of Gaia , swimming and communicating with the dolphins, so much revered by the Polynesians.

- Yachting World

- Digital Edition

The joy of French Polynesia’s traditional multihulls

- June 4, 2021

For over a decade, photographer Julien Girardot has been captivated by the traditional multihulls of French Polynesia and a dream of bringing sailing canoes, or pirogues, back to the motus

I arrived in French Polynesia as a cook and photographer on the scientific research yacht Tara , just passing through. But I ended up settling here for a decade; partly because of my passion for sailing pirogues but also because, as a photographer, Tahiti and her islands are a true blessing.

When you think about French Polynesia, you think of traditional multihulls . Before I arrived I read about navigation by the stars, and the ancient history of Polynesians who sailed the Pacific to populate the islands of the Polynesian Triangle.

Before the adventure really began, we met in Tahiti to try out a canoe belonging to one of Ato’s friends. Five minutes after this picture, we reached the beach in a panic, the pirogue was sinking. But seeds have been sown…

I planned to spend one month in Tuamotu, and told myself that I’d hang out with the locals and sail with them aboard their epic outriggers.

Living on Fakarava, an atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago, I became friends with my neighbour, Ato. One day I asked him: “Ato, where are all the sailing canoes?”

He told me that when engines first arrived in French Polynesia with the ‘popa’a’ (white people) and the nuclear testing programme in the 1960s, the locals were quickly impressed by having so much power with so much ease. No more sails to manage, no more tricky boatbuilding…

The nuclear test programme needed manpower and many Polynesians were hired. T hey started to earn something new for them: money. Islanders embraced modernity, and the sailing canoes were soon gone .

One day, as we were exploring a motu, I asked Ato: “Shall we build a sailing canoe?” He said yes straight away.

After Tara I came back to Fakarava and we launched a non-profit organisation to realise the dream or returning traditional multihulls to the island.

Va’a Iti, starting small

Va’a Iti means ‘little canoe’ in Tahitian. As our first project we set out to develop a single-seat trimaran for a hotel in Bora Bora that wanted a model with a Polynesian look but that would very easy to use.

Nestled in the bottom of a valley is the Va’a Iti construction site – Alexandre and his partner Charlotte’s garage. Photo: Julien Girardot

Working with Alexandre Genton, a talented local boatbuilder, we built a canoe based on a V1 canoe, which is a sport paddling canoe with one outrigger.

Single outrigger canoes are an institution in Polynesia, and Polynesian champion paddlers dominate the podiums at international competitions.

Article continues below…

Pacific castaway: Marooned for months in a pandemic

Immersed and weightless in the warmth of the endless blue, I looked down and could see only fathomless depths below…

Jzerro: The oceangoing Pacific proa

The great Californian Gold Rush of the 1840s and 1850s saw over a quarter of a million people follow the…

This was my first canoe construction and the design was successful, though I came to understand what an old seadog I had met a long time ago in St Malo meant when he told me: “When it comes to boats, the best way to end up a millionaire is to start out as a billionaire!”

But what I gained by living this project was much more valuable than the money.

The next build was a larger Va’a Motu for the hotel, whose owner wanted a modern version of a traditional canoe for their beach club.

The single-seat Va’a Iti trimaran developed for a hotel in Bora Bora. Photo: Julien Girardot

This canoe was 20ft long, built of kauri wood using strip planking, while the rig was made from carbon windsurf masts. There is no rudder so the sailor helms in the traditional Polynesian way, with a paddle in the water.

A dream, Te Maru O Havaiki

Te Maru O Havaiki means ‘the shadow of Havaiki’ and is the realisation of a dream – or certainly of the fantasy that I had as a first-time visitor to the Pacific.

Now, I understand that for French Polynesian locals what is past is past. Here people think of the now, the present. The future and past are not so important; it’s another perception of life. They say of people in the islands: ‘They’ve got the time, and people from busy cities, they’ve got the clock.’

Making the two ‘iakos’, the linking spars that connect the ama to the main hull. Construction was complex due to their shape, with marine plywood, strip planking and hard foam core wrapped in composite. Photo: Julien Girardot

Te Maru O Havaiki is a 30ft Va’a Motu (outrigger canoe) designed by a local architect, Nicolas Gruet, and also built by Alexandre Genton.

The build created the opportunity to train two young people from Fakarava, and one of these young men, Toko, hung in right to the end of the construction. He proved to be an excellent laminator as well as disconcertingly natural at sailing the 30ft canoe, which is not an easy machine for a beginner to handle. The Paumotu people have an incredible ease with the water.

For the children, there was the tradition of the ‘titiraina’, a model of a sailing dugout they played with and raced; a fun game which also allowed them to understand the wind and the sea from a very young age. Photo: Julien Girardot

The project secured sponsorship from the French marine preservation agency, which gave us almost €40,000. They liked the local values and tradition, but the most interesting element for them was the scientific element of the project. For them we had to map an area of Fakarava’s lagoon using kites equipped with cameras!

For more than two months we sailed almost every day, skimming the lagoon from east to west and from north to south, sometimes camping rough for two or three nights to explore further.

During each outing we learned a little more, and gained confidence by sailing with the same crew.

We start to dare to sheet on a little more. The canoe is fast, but on one tack it is unstable. Whenever we tack, we shake out or put in a reef, it’s a delicate balancing act. Others, more courageous than us, sailed with just two people, and later were able to turn by gybing. Three crew is fine, but you have to reef… four is better, five is ideal.

Polynesian celebrations for Te Maru O Havaiki’s launch day. Photo: Julien Girardot

In the end, a government inspector from maritime affairs decided, after a stability test, not to register the dugout because it is too unstable. He is not a sailor, nor Polynesian, but freshly arrived from Dunkerque, where his job was to license cargo ships.

I don’t think he understood the importance of the shape of our canoe and it was painful at the time, but understandable with hindsight.

The dugout canoe in this configuration, with only one ama, will not be a 100% safe boat. Instead we will transform the canoe into a trimaran. The Va’a Motu association reconvened to re-elect a new board in April 2021. Now we will write a second chapter, but this time in a trimaran. Te Maru O Havaiki continues to tell the story of the evolution of multihulls.

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams. Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

‘Ike: Knowledge and Traditions

Holokai: voyages of hōkūle’a, herb kawainui kāne: founding of pvs; building and naming hōkūle‘a, herb kawainui kāne: ships with souls (with a bibliography of traditional canoe building), herb kawainui kāne: in search of the ancient polynesian voyaging canoe (designing hōkūle‘a), herb kawainui kāne: evolution of the hawaiian canoe, ben finney: founding of pvs; building hōkūle‘a, kenneth emory: launching hōkūle‘a march 8, 1975, sam low and herb kawainui kāne: sam ka'ai and hōkūle‘a 's ki'i, hōkūle’a photo gallery, building hawai‘iloa : 1991-1994, sam low: sacred forests: the story of the logs for the hulls of hawai‘iloa, koakanu: traditional hawaiian canoe-building (1916-1917), edgar henriques: hawaiian canoes (1925), s.m. kamakau: the building of keawenui'umi's canoe, hawaiian deities of canoes and canoe building, plants and tools used for building traditional canoes, parts of a traditional canoe, hawaiian canoe-building traditions (1995, online at ulukau), in search of the ancient polynesian voyaging canoe (1998), herb kawainui kāne.

Polynesia began with the voyaging canoe. More than three thousand years ago, the uninhabited islands of Samoa and Tonga were discovered by an ancient people. With them were plants, animals, and a language with origins in Southeast Asia; and along the way they had become a seafaring people. Arriving in probably a few small groups, and living in isolation for centuries, they evolved distinctive physical and cultural traits. Samoa and Tonga became the cradle of Polynesia, and the center of what is now Western Polynesia.

More than two thousand years ago, Polynesians exploring eastward, during times when winds shifted away from the prevailing easterlies, discovered the Tahitian and Marquesas Islands. From these "centers of diffusion" explorers reached outward as far as Hawai'i to the north, Easter Island to the east, and New Zealand to the southwest. Before European open ocean exploration began, Eastern Polynesia had been explored and settled.

Canoe Design Evolution

Because the exploration and settlement of Eastern Polynesia originated from the same centers, the design of the canoes must have been much the same throughout. But that design disappeared. Ships are as mortal as their makers. Except for fragments of ancient canoes excavated on New Zealand and pieces of a large canoe recently unearthed from a bog on Huahine, there is no hard evidence.1 Except for a petroglyph on Easter Island, and passing references in the old legends, there is no descriptive record.

The Easter Island canoe petroglyph found at Orongo and Herb's rendition of what the original canoe may have looked like.

Over the following centuries, this "archaic" form evolved into designs which became "classical" to each island group-specialized to meet the challenges of local winds and seas and timber resources. When Europeans arrived, they found pronounced differences in canoe designs from one island group to another.

One such design change was witnessed by Europeans. Schouten in 1619 saw only the tongiaki double canoe in Tongan waters. When the Cook expedition arrived in 1773, the drawings of double canoes by the artist Hodges depicted a transition from the tongiaki to the swift kalia--a borrowing of the Micronesian "double-ender" concept. When Cook visited again five years later, the artist Webber's drawings suggest that he saw only the new kalia.2

Design Strategy for Hokule'a3

What were the design features of the ancient double-hulled voyaging canoes (vaka taurua)? Applying the "age-distribution" method, we assume that similarities in hull shape, sail shape, and construction techniques which were widely distributed when Europeans arrived must have been carried outward from the centers of cultural diffusion during ancient eras of exploration and settlement, and may be accepted as features of the ancient canoes. By limiting the design of a voyaging canoe to these features, a performance-accurate replication of the ancient canoe is possible. Such features formed the design vocabulary of the replica Hokule'a.

Construction Drawings for Hokule'a

Kenneth Emory and I went through all designs of canoes recorded in early drawings and in other evidence and sifted out those features of hull design and sail plan which by their wide distribution may be taken to be most ancient. These I applied to the conceptual design. From my own experience with the Pacific swell and in consultation with more experienced sailors, I arrived at a waterline length of 55 to 60 feet as one that could handle the swells yet recover easily in the troughs, and Emory found that this could be taken as an average for the length of canoes used in the 18th and 19th centuries for long distance voyaging in the Tuamotus and Tahitian islands. Canoes of far greater length would put great stress on the lashings. The double-ended ndrua of Fiji and kalia of Tonga were of greater length, but these carried a smaller hull to windward involving less stress on lashings than two hulls of equal length, and were generally used on shorter voyages, which means during periods of predictable weather. (Click here for a photo of "Takitumu," a modern reconstruction of a Cook Islands kalia.)

Some classical Hawaiian features were included which did not affect performance, such as the styling of the bow and stern pieces (manu) and the arched cross-beams (not really ancient, invented by Kanuha several centuries ago).

Kino (Hull): Hulls were carved from logs wherever timber of sufficient size was found. The depth of a hull might be increased by adding one or two courses of boards (strakes) fitted and lashed above the hull's upper edges (gunwales). On atolls where large timber was not available for dugout hulls, the use of gunwale strakes was transformed into a method of building entire hulls "plank-built" over a dugout keel piece, with ribs and thwarts inserted to strengthen the planking.

All hull and sail design features must be compromises. Where paddling was the primary power mode with sail as auxiliary power, round-bottomed hulls were favored for their maneuverability; but where sailing was the primary purpose, hulls were deeper or had a greater amount of "V" shape along the keel for better tracking through the water. Such hulls are less maneuverable but offer lateral resistance to the water, reducing leeway (the sideways skidding of a boat hull away from the wind when sailing against or across the wind). Because the great distances covered by some ancient voyages could not have been accomplished by paddling, we may assume that the voyaging canoes were primarily sailing machines, with paddling being auxiliary. These were not the flat-sided "V" hulls of modern catamarans, but a rounded "V" by which the maximum floatation capacity could be carved from the natural shape of a log. A rounded "V" hull, with the sides swelling outward in convex curvature, is also stronger than a flat-sided "V" hull because it adds the strength of an arch against the impact of waves.

Where hulls were of unequal length, the smaller hull was carried on the left, and called the ama-the same term for the float outrigged from the left side of single-hull "outrigger" canoes. The one exception is the island of Tubuai in the Australs, where the ama is carried on the right; but today no canoe maker on Tubuai can explain why.

Below the waterline the curvature of all Polynesian hulls is convex, both in length and in section, with no cavities. Longitudinal curves below the waterline are smooth-flowing from bow to stern, creating a gentle entry at the bow and an equally gentle departure at the stern-features necessary for a "soft" ride and maximum hull speed. In these curves there are no abrupt breaks-no "chisel" bows to snag the water and make steering difficult, no abrupt departure at the stern which creates turbulence. For best speed the hull curves are faired out as much as possible (canoe builders knew how to use a flexible fairing strip to check their hull curves), with no hollows or flat areas to cause turbulence.

The volume of Polynesian hulls aft of the midsection is slightly greater than the volume forward of the midsection. This extra floatation aft offsets the tendency of canoes to "squat" at the stern when under a hard press of sail.

Because double canoes are held together by rope lashings, the hulls must be assembled closer together than the hulls of modern catamarans. This narrows the space through which water must pass between the hulls. To avoid excessive turbulence between the hulls, the greater volume aft of the midsection should be obtained by greater hull depth, rather than increasing hull width.

Pe'a (Sails): My first preliminary drawing for Hokule'a (1973) featured triangular sails carried with the peak of the triangle downward and mounted on straight spars, a design which by its simplicity and wide distribution seemed to be the most ancient form. This sail plan was modified later in 1975 and again in 1976 with a curved boom to more closely resemble the Hawaiian sails at the time of European contact. However, experiments in 1991 and subsequent voyages have demonstrated that the simple triangular sail carried on straight spars is no less efficient; moreover, it is easier to furl and handle on deck when the rig is dropped to ride out bad weather.

Sails were of pandanus matting except in New Zealand, where pandanus could not be naturalized and flax was substituted. Sails were cut from long rolls of matting seldom more than 18" wide, double plaited of strips 3/16" to 3/8" wide in a twill pattern, changing to a check pattern along the edges for strength.

The sail was built up by overlapping the edges of these strips and sewing them with a running stitch. The outer edges of the sail were hemmed over a rope. A line was fastened with a running hitch at intervals along the outer edges. This line was then tied to the spars with a spiral lashing or with many short lengths of line.

Curved booms, if desired, could be scarfed up from shorter poles to achieve the desired overall curvature and length. The long scarf joints were strengthed with splints and seized up with small line. Spars could also be strengthened at those places where sheets and stays were attached by seizing splints to them.

For a large voyaging canoe having no labor-saving winches, two sails are easier to handle than one large sail. The foresail should be the larger. By distributing the effort over two sails, the moment of capsize is lowered, imparting greater stability to a vessel which, being held together by lashings, is necessarily narrower than a modern multi-hull. If the vessel appears to be overpowered while sailing off the wind, sail area can be quickly reduced by dropping the aftersail.

'Iako (Connecting Cross-beams): A true replication of an ancient canoe should have crossbeams shaped from straight poles-the method most widely distributed. The arched crossbeam is a feature of the classical Hawaiian double canoe, invented only four centuries ago by the designer Kanuha in the time of Keawe.4

In a quartering sea the hulls of a double canoe will work against each other. By inter-connecting the crossbeams with diagonal bracings of strong rope, this motion can be restrained, adding very little weight to the vessel.

While most cross-beams were lashed to the gunwales, the connection of the two hulls could be strengthened by two or more lower crossbeams let through the hulls, as seen in the drawing of a beached Tahitian double hulled sailing canoe by Webber, with Cook.5

The flashing speed of modern catamarans results from their wide beam and rigidity of construction, made possible by steel fastenings. The vaka taurua is a slower sailer. Assembled with cordage, it lacks the rigidity of modern multihulls, and the hulls must be closer together to reduce stress on the cross-beams. Assembly by lashings seems to offer one advantage. As noted on the replica Hokule'a, the cross-beam lashings absorb much of the shock of waves that beat against the hulls, a pounding that is transmitted throughout a modern vessel.

Pola (Decking): Decking may be of light planks if these are supported by a webbing stretched between the crossbeams. Lighter planking means less weight. Deck planks should be spaced with gaps through which heaping waves can rise. Without such gaps to relieve wave pressure, strong surges can break the decking. In this compromise, it's better to be safe than dry.

Planks can be added over certain areas of the windward hull on long tacks, even out to the ends of the crossbeams, where they will deflect the splash of waves, and serve as hiking boards for the crew during gusts of wind.

Mast steps: Wind pressure on the sail drives the mast downward. Such pressure should not be borne by only one crossbeam. The masts may be stepped upon strong longitudinal beams (kua), each distributing the downward thrust over a least three crossbeams. Once the optimum center of effort is found by experimentally moving the masts forward or aft over these steps, additional crossbeams may be added under those points.

Manu (Bow and Stern pieces): As I discovered while sailing Hokule'a, end pieces have a practical function. Eastern Polynesian end pieces typically rise higher at the stern than at the bow. The sternpiece appears to break a following wave crest that might otherwise board the canoe. When the canoe surfs on a following wave, plunging forward, the bowpiece, in a burst of spray, helps prevent the bow from "boneyarding" into the back of the wave ahead.

As expressed in the carving of end pieces, symbolism associated with birds or bird-man (manaia) forms was widely distributed. The term manu for the abstract shape of the classical Hawaiian end piece suggests that the archaic form may have represented birds. A pre-classical Maori bowpiece unearthed on New Zealand has a long neck and the head of a bird-man figure. European drawings of some Marquesan canoes, and old Marquesan canoe models, have bird-like shapes when viewed in profile, with the head at the bow, the gunwale strakes resembling wings, and the stern-piece appearing as the tail. Feathers were widely used as pennants flown from the end of a spar (Tahiti, Hawaiçi), or black feathers hung from the stern piece (New Zealand); as bunches of feathers at the stern (Marquesas); and as feathers worked into the gunwale lashings (New Zealand, Marquesas).

Hale (Deck Shelter, pronounced "ha-lay"): This may be a construction of light poles and purlins covered by thatching and/or tightly plaited matting. The shelter should be easily moved. On long reaches or tacks it should be positioned over the windward hull.

Sailing the Vaka Taurua

Steering: The idea of steering a sixty-foot multihull without a rudder has intrigued conventional yachtsmen on their first sails aboard Hokule'a. On a downwind course the steering paddle is handled in the manner of a rudder, and long sweeps were used on some Polynesian canoes. On any other tack, however, the steering paddle is held against the lee side of the hull near the stern. The pressure of the water against the blade helps hold it fast, and very little effort is required to hold a heavy steering paddle in place. A slight twisting pressure to hold the leading edge of the blade firmly against the hull prevents the flow of water from getting under the blade and kicking it away. For this reason, steering paddles were often carved flat on the side held against the hull, and concave on the other.6

At a canoe's first sea trials, the masts should be experimentally shifted forward or aft until the center of effort is balanced with a slight weather helm, so that when the paddle is raised, decreasing its lateral resistance to the water at the stern, the stern will fall off the wind, turning the vessel into the wind. When the paddle is lowered, creating more lateral resistance at the stern than exists at the bow, the canoe will turn off the wind.

The Polynesian paddle creates less drag than the modern rudder, and is put in the water only when needed.

Steering with the Sails: On long reaches, steering paddles may not be needed at all; the canoe can be rigged to steer itself by sails alone. The aftersail is eased out slightly more than the foresail. As the canoe rounds up into the wind, the aftersail luffs and loses power. Pressure on the foresail now causes the vessel to turn off the wind a few degrees. The aftersail is again presented to the wind; it fills, and the vessel begins another slight turn to windward. Sawing slightly into the wind and off the wind, the canoe will steer itself on a close reach for hours.

Tacking: In light or moderate winds the double canoe will come about (turn into and through the eye of the wind) without stalling if the crew backs the foresail, harnessing the wind to push the bows over. In a strong breeze, however, it's difficult to come about without sailing. Then it is better to jibe (make the turn with the wind astern) by luffing the aftersail until the foresail powers the vessel well off the wind, then close-hauling both sails as the stern passes through the eye of the wind. Here, the blades of the steering paddles are held at full depth to grip the stern in the water. A double hulled vessel is slow to turn because its two hulls give it twice the waterline length of a sailboat of the same length.

Shortening the Sails: Sails and booms were brailed up to the mast while temporarily not in use.

In the path of a dangerous squall, the prudent act would be to release stays and drop spars and sails, lowering the center of capsize as much as possible. The canoe is brought into the wind, and the forestay (a running line) is eased out, lowering the mast aft. The shrouds will hold the mast in fore-and-aft alignment with the canoe as it comes down.

Lacing between sections of sail matting might be quickly removed to shorten sail.

Storm sails may be simple, small, strongly made sails lashed to short straight spars with stays and shrouds already attached. Rolled up and stored away, these can be raised to power a canoe in moderate gales.

Leeboards: The use of leeboards to diminish leeway and help a vessel without a keel go to windward was a Chinese invention which never got to Polynesia, but the same effect was accomplished, when required, by a row of men holding paddles against the lee side of a hull. This takes practice, but it can add ten degrees to a canoe's windward performance.

Storm Survival: An approaching storm meant getting down sails and spars, even jettisoning the deck shelter if necessary to reduce windage, and laying out a sea anchor on a very long line. Strong baskets are said to have been used in Hawai'i.

If necessary, the next step would be to deliberately swamp the canoe, a technique that modern minds find incomprehensible, but which is still commonly practiced in Micronesia. Wooden hulls provide sufficient floatation so that the crew can ride within the hulls with their heads and shoulders above water.

Being mostly under water, the canoe will not be buffeted about. Most important for navigation, it will not skate downwind, but will hold position fairly well.

After the storm has passed, the hulls can be bailed out and the voyage resumed. It's helpful to have additional positive flotation to raise the gunwales with enough freeboard to facilitate the bailing. On the old canoes, coconuts served as positive floatation as well as providing food and drink. These, and other cargo, were held down in the bottoms of the hulls under netting. Today, any inflatable devices secured under netting can be inflated to give the hulls more freeboard. Rigid foam or empty containers packed under the bow and stern covers will also add floatation.

1. "The main evidence that we have of what the voyaging canoes were like came from an island called Huahine, which is about 110 miles west of Tahiti. In an area called Maeva, a hotel called the Bali Hai was being built and when they were digging up the ground, they found some canoe bailers. They called Dr. Sinoto from the Bishop Museum and he went down and conducted an excavation. He thinks that six hundred to a thousand years ago there was a canoe under construction here and the work place was hit by a tsunami which buried the canoe under mud and sand and preserved it by cutting off the oxygen that causes wood to rot.

"Sinoto unearthed planks of the canoe with coconut fiber (aha) still holding them together. There was a knot in the plank and what the builders did was to put wood in from behind and lashed the two pieces of wood together to make a sandwich. Dr. Sinoto guesses that this canoe was 72 feet long, ten feet longer than Hokule'a" (Nainoa Thompson, Speech at Kamehameha Schools, April 1998).

2. [Haddon & Hornell explain, "The principal features wherein the tongiaki differed from the kalia were: (1) in the approximate equality of the two hulls; (2) in sailing, the same ends were always directed forward and in consequence the manipulation of the sail was entirely different; (3) the mast was much shorter and had a forked head in which the yard rested, with the tack of the sail confined by ropes between the prows and not stepped at the fore end of one hull; (4) the presence of an outrigger balance spar; (5) the deck platform was relatively larger and extended considerably farther aft than in the kalia; (6) the deck shelter was a tunnel-shaped hut without a platform above the roof. (Canoes of Oceania, Bishop Museum, 1936, reprinted 1975, 271-272).] (Click here for a photo of "Takitumu," a modern reconstruction of a Cook Island kalia.)

3. Kane lists the following people as important contributors to the design and building of Hokule'a:

Kenneth Emory: consultation on ancient design features. Herb Kawainui Kane: conceptual design and establishing design parameters in a general drawing. Rudy Choy: consultation and advice on hull design. Vince Bartelone: the hull-lines drawing Kim Thompson: the lines drawings for the end pieces (manu) Warren Seaman: lofting the hulls and laying up sections and stringers on the strongbacks. Curt Ashford and Malcolm Waldron: chief shipwrights. Jim Ebersold, Calvin Coito, and others: boat carpenters. Wright Bowman, Sr. and Wright Bowman, Jr.: crossbeam construction. Keola Sequeira: carver of the koa mast heads (he donated the koa). Bob Fortier: protective fiber-glassing of the wooden hulls.

Kane recalls: "These were most of the hands-on guys. Additionally there were part-time carpenters and a host of volunteers. Most of the board members donated some time. Publisher Carl Lindquist brought his family down to help with the disagreeable task of poisoning the interiors of the hulls to prevent rot. Kawika Kapahulehua facilitated air transportation for materials and supplies. Slim's Power Tools donated the use of power tools. Many merchants helped procure supplies and materials at cost. Dillingham Corporation donated the use of the building premises. I don't remember the name of the trucking company that gave us a price break to haul the completed parts over the island to Kualoa Park (how I obtained that launching site from mayor Frank Fasi after the State gave me the run around for months on San Souci beach is another story). The U.S. Marines at Kane'ohe brought equipment to lift and set the hulls in perfect position for the lashing up, which was done over five weekends by many volunteers.

4. Malo, David. Hawaiian Antiquities. Honolulu: Bishop Museum. 130.

5. Beaglehole, The Voyage of the Resolution and Discovery, Cambridge, 1967, Pl. 25-b.

6. "In the earliest days of Hokule'a, when she was going through sea trials, the steering mechanism was like the kind we use on a six man canoe but the problem was that a six-man canoe weighs 600 pounds and Hokule'a weighs-fully loaded-about 24,000 pounds and guys who were trying to steer her were getting knocked out, ending up in the hospital, and it wasn't working and I was looking at that thing and saying, 'Oh, man, it is really going to be a long trip.' And so some of the beach boys said, 'We are not going to do it this way anymore. We have got to come up with a steering sweep.' And so they designed a steering sweep that would work-from their experience at Waikîkî-and it solved the steering problem. And the steering sweep that they pulled out of that swamp in Huahine [see note 1]-it was discovered after the beach boys figured out how to design a sweep for Hokule'a-and this sweep [excataed in Huahine] is very similar in design and only two feet shorter than the ones we use to steer Hokule'a" (Nainoa Thompson, Speech at Kamehameha Schools, April 1998).

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Wharram Design Book (Build Yourself a Modern Sea Going Polynesian Catamaran) Paperback – January 1, 1999

- Print length 73 pages

- Language English

- Publisher James Wharram Designs

- Publication date January 1, 1999

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Product details

- ASIN : B003HH0H9C

- Publisher : James Wharram Designs; 5th or later Edition (January 1, 1999)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 73 pages

- Item Weight : 11.2 ounces

- Best Sellers Rank: #6,457,222 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books )

About the author

James wharram.

James Wharram is one of the pioneers of the development of sailing catamarans. He was the first in the UK to sail with a catamaran offshore, sailing across the Bay of Biscay in 1955 and crossing the Atlantic in 1956. He, together with two German girls, was the first to sail a catamaran – 12m ‘Rongo’ - across the Northern Atlantic from West to East in 1959.

His inspiration has always come from early watercraft and seafaring, particularly the double canoes of the Polynesians with which the Pacific islands were settled. He has made it his life’s career, in the last 45 years together with his design partner Hanneke Boon, to design such type of vessels for other people to build and sail the oceans. They are now well known for a distinctive range of catamarans with thousands of them sailing the oceans of the world.

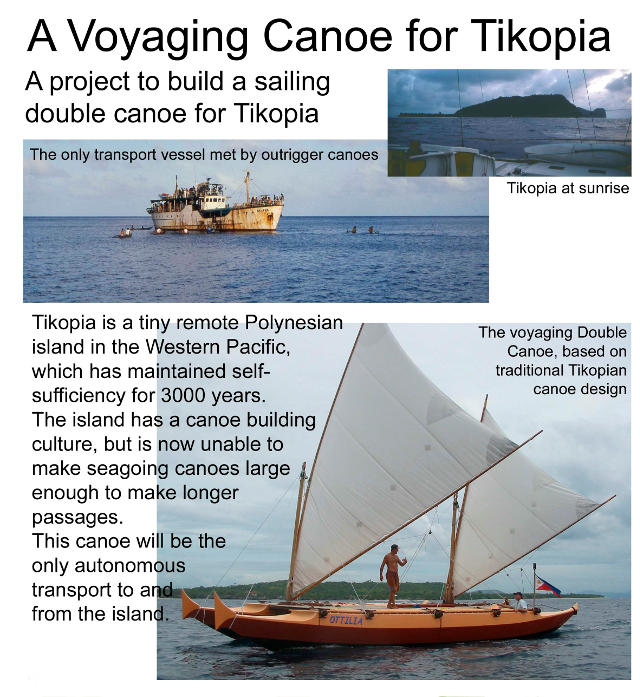

Since the 1990s, James and Hanneke have been making further studies of canoeform craft, voyaging the Pacific and Indian oceans on their own 19m double canoe ‘Spirit of Gaia’ as well as sailing the 4000Nm ‘Lapita Voyage’ in 2008-9. This voyage followed the ancient migration route into the Pacific on two ethnic double canoes from the Philippines to the Polynesian islands of Anuta and Tikopia. This voyage has proven the feasibility of migrating on canoe craft out of SE Asia, reinforcing the theories of Eric de Bisschop.

In 1968 James Wharram wrote the book ‘Two Girls Two Catamarans’ about his first pioneering catamaran voyages, available from the author's website wharram.com. His second book co-written with Hanneke Boon is his autobiography ‘People of the Sea’.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Log in or Sign up

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly. You should upgrade or use an alternative browser .

CSK / polynesian concept catamaran

Discussion in ' Multihulls ' started by djeeke , Apr 14, 2009 .

djeeke Junior Member

Hi all, I have been directed to this forum as it seems there are a lot of knowledgeable people here. First this forum did not seem the right one to ask my questions so I never subscribed... I guess I might we wrong so here I am... We are looking at buying a catamaran (budget limits us to older/smaller boats). Our intent is to find a boat capable of taking us anywhere, so its design must have ocean sailing incorporated. We would be a couple sailing, so singlehand capability is required, occasionally we might take on some family or friends. We spotted a 37ft CSK catamaran for sale and are trying to get some feedback on this boat... There have not been many of these boats built and it seems it is very difficult to obtain first hand information on them. The only feedback I got till now is mixed, it seems to sail well, the hulls would be very narrow and access to the hulls from the cabin very difficult (have not seen any pictures of that area so have no clue on this). The person that provided this info also stated that he would not consider crossing an ocean with this boat. (which if confirmed would simply take the boat of our list) If there is anyone here with knowledge about these boats:?: I would be happy to read your comments... Thank you for sharing knowledge and experience

catsketcher Senior Member

Do more research The second cat to sail around the world was a CSK - World cat. They were also crossing oceans when most of the current designers weren't even born. Access into the hulls will be a problem and a 37ft CSK is not the same as a 37ft modern cat. However I saw a 34 ft (ish) CSK being well sailed around the world when I first went cruising. The French family loved it. Whether this boat is a good example of a CSK cat I don't know. There is a CSK forum at Yahoo that you should try to get into. They will know more. Just a word of warning - make sure it is what the owner says it is. Some self designed boats all of a sudden get a proper designer's stamp when up for sale. Put an image up here or on the yahoo site. cheers Phil

What about tris If it is not the room you are after you should also consider tris. I am a big fan of the Searunner tris by Jim Brown. Lots in the US and a few in Europe. Tris are cheaper and do pretty much the same as cats without the room.

This Is the type of boat I am talking about... it is listed for sale here -click- I did contact Choy design, they were so kind to respond to my queries and told me to stay away of this type of boat for world cruising ... They did not supervise any of the building of these boats but do recall they had some (even structural) issues over the years... I just had this feedback a few minutes ago and I guess this stops my queries about this design. Too bad, it looked nice, probably a bit small (space inside I mean) for current modern standards but still big enough for us as a couple, high bridgedeck etc... But if the people behind the drawing board say no, who am I to argue !!!

catsketcher said: ↑ If it is not the room you are after you should also consider tris. I am a big fan of the Searunner tris by Jim Brown. Lots in the US and a few in Europe. Tris are cheaper and do pretty much the same as cats without the room. Click to expand...

bill broome Senior Member

have a look at www.sailingcatamarans.com . woods designed some deep vee boats when getting started that might suit you, as they will be old and unfashionable.

rayaldridge Senior Member

If you can get a copy of Buddy Ebsen's book about his boat (which as I recall was quite similar to the boat in the picture) Polynesian Concept, it's a good read. That's the boat he won the TransPac in, beating James Arness in his much larger Seasmoke.

rasorinc Senior Member

You might check out this site for some ideas. They build Polynesian style and have pics. http://www.andy-smith-boatworks.com/wharram/andy_smith_boat_works.htm

Gary Baigent Senior Member

Ray Polynesian Concept was definitely a fine boat and if this one is similar, although with all the cruising accoutrements it will be heavier (PC was a racer but won the Transpac with a large crew however) then it should be a good sea boat. Obviously the builders know something more about the construction - or they're being ultra conservative and overly safety conscious. However if the boat was good, Buddy Ebsen's book was annoyingly bad and a disappointment - giant ego, suppressed arguments and tension, didn't sound like a good time even though they beat 58 foot Seasmoke.

That was the year that Hugo Myers' brand new, very advanced 44 foot catamaran Sea Bird also did the race, as an unofficial entry. Ebsen never even mentions the boat - which pedantic people will agree with since the cat was not an official member of the fleet. However this Myers design, at that time, was the largest open wing deck cat in the world, had a rotating mast, was very light and full of innovation and early high technology materials, a forerunner to all modern racing catamaran design - and yet Ebsen totally ignores it. Sea Bird broke a titanium rudder and was forced to slow down, concerned that the other would also go but still finished well up in fleet. Sorry this is off topic somewhat.

Gary Baigent said: ↑ Polynesian Concept was definitely a fine boat and if this one is similar, although with all the cruising accoutrements it will be heavier (PC was a racer but won the Transpac with a large crew however) then it should be a good sea boat. Click to expand...

![polynesian catamaran design [IMG]](https://www.boatdesign.net/proxy.php?image=https%3A%2F%2Fvanimages.yachtworld.com%2F1%2F0%2F0%2F5%2F5%2F1005598_1.jpg&hash=90cb3972778557ef108fa44d42b76e56)

Gary Baigent said: ↑ Ray However if the boat was good, Buddy Ebsen's book was annoyingly bad and a disappointment - giant ego, suppressed arguments and tension, didn't sound like a good time even though they beat 58 foot Seasmoke. Click to expand...

bax Junior Member

I sailed with Buddy on Polynesian Concept for a daysail back in the early seventies. He was the consumate host, inviting us back to his house where he cooked burgers for us by his cement pond. Of course, it couldn't have had anything to do with the fact that we were interested in buying one of the production Polycons! We sailed one the following day with a couple who bought one of the first ones built. Great day on the water, near Catalina. The wind was up, tore the clew right out of the jib. Being the youngest and most willing on board, I went forward to douse the jib. Had a great time, first high and dry, then up to my waist in green water as the bows dug in, heaven for a teenager! These were my first experiences on a cat larger than a Hobie, and I was hooked, knowing that someday, I'd have a cruising cat. The original and the production Polycons were great for their day, and I imagine could hold their own against many crusing cats today, with the exception of those with daggerboards I would think. FWIW, if I were in the market for a old used cat for coastal cruising I'd consider one if the price was right.

Thanks Bax ! We are looking for more than coastal cruising, someone else already told us he would not consider crossing the pond with one... I guess you share the view...

- Advertisement:

Yes Djeeke, Sorry, that was long winded affirmative. I just got carried away reminiscing! bax

1981 52' CSK ketch rigged catamaran

52' csk catamaran.

Questions about safety of CSK / Polycon Catamarans for cruising

Free 37' CSK hull molds in Cali

Trimaran derived from polynesian Va'a

- No, create an account now.

- Yes, my password is:

- Forgot your password?

Modern Catamaran Trends: Gimmicks or Valid Design Ideas?

The celebrity of the catamaran is not only swelling in racing, but also for cruising catamarans. At their conception, the atypical design enabled cats to sail faster and in shallower waters with less wind and crew than other sailing vessels. But for years the unorthodox design met with skepticism, leaving the catamaran with little commercial success. Additional challenges to adoption of early versions of cruising cats were the small, very cramped interiors by modern day standards, was heavy and lumbering handling abilities. Many sailors used to say they “were built like tanks and sailed like bricks”.

However, sailors soon realized that nothing could beat the comfort, speed, and safety of a well-designed modern catamaran as a cruising yacht. These vessels can achieve the highest speed for the smoothest ride and boast the most interior space and greatest safety of most ocean-going vessels. Sailors of all types are quickly overcoming earlier prejudices against the multihull design as contemporary design trends continue to produce catamarans that are faster, more exciting, more visually interesting, and safer than ever before.

The New Trends

Fun and interesting new trends in catamarans make sailing even more exciting than ever before. However, innovations are only useful if they contribute to good design, construction, and safety principles and it should fit your sailing purposes. Let’s take a look at some trends in modern cats:

1. Larger Catamarans for Fewer Crew

The new generation of catamaran, using modern composite construction and engineering can be built lighter, larger, and more spacious with very good power-to-weight characteristics. Currently, the trend leans increasingly towards larger catamarans. The average catamaran for a cruising couple now tends to be more in the 45ft to 50ft range. With composite engineering and installation of technologically advanced equipment, e.g., electric winches, furling systems, and reliable auto pilot, it is now possible for shorthanded crews to confidently sail larger boats with larger rigs. Technology has enabled modern catamarans’ bigger volume with more stiff and torsion resistant construction, without compromising stability and safety.

2. Inside Out: Convertible Main Living Areas