WELCOME TO THE

NAVAL POINT CLUB LYTTELTON

Welcome to The Naval Point Club Lyttelton Incorporated (NPCL). The Club was established in 2001 following the amalgamation of the Banks Peninsula Cruising Club est. 1932; and the Canterbury Yacht and Motor Boat Club est. 1921. With over 700 members the Club, based at Magazine Bay in Lyttelton, provides opportunities for boats of all classes, including junior/youth dinghies, senior dinghies, windsurf, trailer yachts, keelboats, powerboats, waka, jet-ski, swim and other open water sports. Naval Point welcomes anyone interested in water sports - let us help you access the fantastic water of Lyttelton Harbour/Whakaraupo and the wonderful bays of Banks Peninsula/Horomaka. Off the water, NPCL hosts monthly talks on sailing related topics including boat maintenance, design and construction. Our 'old salts' meet every second month over a long lunch to enjoy the camaraderie of being a sailor and our clubhouse is open regularly for functions and pre and post sailing for members and their guests.

- ← Newer

- Older →

SIGN UP TO RECIEVE OUR LATEST NEWSLETTERS

Get the Latest Updates and Events

NAVAL POINT CLUB APP

Download the free Naval Point Club app to receive sport updates from Naval Point Clup.

Go to the App Store or Google Play, search for Naval Point Club.

Magazine Bay, Lyttelton, New Zealand

03 328 7029

manager @navalpoint.co.nz

SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTERS

- Yacht Clubs

- Notices of Race

- Learn to Sail

Class Associations

- Information

Discover the Magic of Sailing

We promote canterbury yachting and represent the interests of all the yacht clubs and class associations in the area..

Clubs run all sorts of activities from learn to sail courses, racing, coaching, regattas, cruising and social activities.

The city of christchurch is perfectly located for sailing., the notice of race for upcoming events:.

Come Sailing

Helpful Information

Naval Point Yacht Club

With over 750 members the Club, based at Magazine Bay in Lyttelton, the Naval Point Yacht Club provides opportunities for boats of all classes, including junior/youth dinghies, senior dinghies, windsurf, trailer yachts, keelboats, powerboats, waka, jet-ski, swim and other open water sports.

Naval Point welcomes anyone interested in open water sports - let us help you access the fantastic water of Lyttelton Harbour/Whakaraupo and the wonderful bays of Banks Peninsula/Horomaka.

- Dinghy Sailing

- Trailer yachts

- Crews - availability list

- Swim at Naval Point

- Paddleboarding

- Power boats

- YACHT DESIGN

- YACHT MARKET

- YACHT CLUBS

- YACHT HOTELS

- CHARTER YACHTS

- YACHT SHOWS

- REGATTAS & RACES

- YACHT ACCESSORIES

- YACHT APPAREL

- SAILOR GUIDE

Contact us: [email protected]

© Copyright 2023 - Oceanshaker.com

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

- Latest videos, from 2024

-300x250-202108170128.png)

Do you sell tickets for an event, performance or venue? Sell more tickets faster with Eventfinda. Find out more. Find out more about Eventfinda Ticketing.

Naval Point Club Lyttelton

Erskine Point, Lyttelton

(03) 3287029

- www.navalpoint.co.nz

Established in 2001, the Naval Point Club is the result of uniting the Banks Peninsula Cruising Club and the Canterbury Yacht and Motor Boat Club. We have over 1000 members and we are based at Magazine Bay, Lyttelton.

Naval Point Club has excellent facilities, is an all-tide venue and offers many services to its members. A comprehensive member's handbook is published yearly listing the full race calendar, social and cruising events, membership, fleet registers, contact details and Club rules. The Club's active fleets include vessels from the small Optimist dinghies to large keel boats, with substantial numbers of trailer yachts, catamarans and dinghies. As well as sailing vessels, club membership includes powerboats, jet skis and launches, waka ama, kayaks, stand up paddle boarders and swimmers.

Are you responsible for Naval Point Club Lyttelton?

You can claim this venue to manage this listing's details.

Advertise with Eventfinda

Popular Events Close By

Lyttelton Craft and Treasure Market

Collett's Corner , Lyttelton, Christchurch District

Sat 20 Apr 9:00am – more dates

You Should Be Dancing

The Loons , Lyttelton, Christchurch District

Fri 17 May 8:00pm

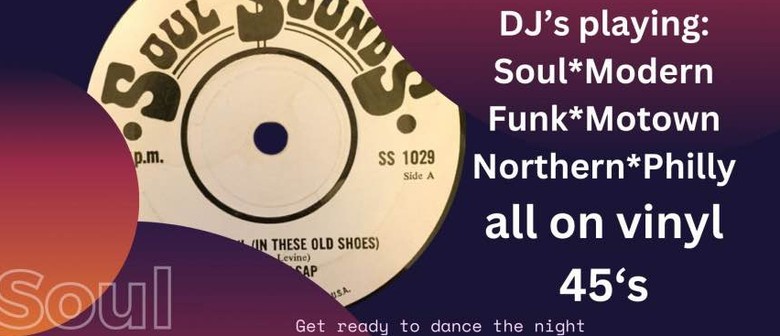

The Soul Sounds Vinyl Night

Wunderbar , Lyttelton, Christchurch District

Sat 27 Apr 9:00pm

Oddisee - Christchurch

Thu 9 May 7:00pm

Blonde Redhead | Lyttelton

Mon 24 Jun 7:30pm

Thu 21 Nov 2024 8:00pm

Hannah Everingham

Fri 3 May 8:30pm

Beneficiary 414127193 - Hoha - Moider Mother - No Exit

Fri 10 May 8:30pm

Past events at Naval Point Club Lyttelton

Seaweek whakaraupō harbour clean up.

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Sun 7 Mar 2021

NZ Slalom Nationals 2019

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Wed 9 Jan 2019 – Sun 13 Jan 2019

Little Ship Club of Canterbury

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Thu 15 Jun 2017 – Thu 30 Nov 2017

Learn to Sail 2

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Tue 4 Oct 2016 – Thu 6 Oct 2016

Blind Boy Paxton

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Fri 11 Mar 2016

Southern Hector's Fundraising BBQ

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Sat 16 Feb 2019

Seaweek Whakaraupo-Lyttelton Harbour Clean-Up

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Fri 9 Mar 2018

Seaweek - Lyttelton Harbour Community Clean-Up

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Sun 12 Mar 2017

Learn to Sail

Naval Point Club Lyttelton , Mon 26 Sep 2016 – Wed 28 Sep 2016

Post a comment

Log in / sign up.

Continuing confirms your acceptance of our terms of service .

Choose your location

- New Zealand

- Hawke's Bay / Gisborne

- Palmerston North

- Christchurch

Free Membership

Before you go, would you like to subscribe to our free weekly newsletter with new events from your favourite artists & venues?

Enter your email below, click on the Sign Up button and we’ll send you on your way...

No thanks - I'm already an Eventfinda member (or I don't want to join)

Signing you up to our newsletter and taking you to an external link...

Shopping Cart

0 items – $0

Eventfinda does not support your version of IE. Upgrade to the current version .

Eventfinda works best with JavaScript enabled

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Putin’s Shadow Cabinet and the Bridge to Crimea

By Joshua Yaffa

In the spring of 2014, President Vladimir Putin delivered an address in St. George Hall, a chandeliered ballroom in the Kremlin, to celebrate the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula . “Crimea has always been an integral part of Russia in the hearts and minds of our people,” he declared, to a standing ovation. Despite Putin’s triumphal language, the annexation presented Russia with a formidable logistical challenge: Crimea’s physical isolation. Crimea, which is roughly the size of Massachusetts, is a landscape of sandy beaches and verdant mountains that juts into the Black Sea. It’s connected to Ukraine by a narrow isthmus to the north but is separated from Russia by a stretch of water called the Kerch Strait. Ukraine, to which Crimea had belonged, viewed Russia’s occupation as illegal, and had sealed off access to the peninsula, closing the single road to commercial traffic and shutting down the rail lines.

In response, Putin convened a council of engineers, construction experts, and government officials to look at options for connecting Crimea to the Russian mainland. They considered more than ninety possibilities, including an undersea tunnel, before deciding to build a bridge. The Russian state is notoriously inefficient at following through on the quotidian details of government administration; its more natural mode is building projects of tremendous scale. In keeping with this tradition of expanse, and expense, the bridge would span nearly twelve miles, making it the longest in the country, and would cost more than three billion dollars. When completed, it would symbolically cement Russia’s control over the territory and demonstrate the country’s reëmergence as a geopolitical power willing to challenge the post-Cold War order.

The bridge would be a demanding and technically complex project, however, and at first there were doubts about who would be willing to undertake it. Then, in January, 2015, the Russian government announced that Arkady Rotenberg, a sixty-three-year-old magnate with interests in construction, banking, transportation, and energy, would direct the project. In retrospect, the choice was obvious, almost inevitable. Rotenberg’s personal wealth is estimated at more than two and a half billion dollars, and the bulk of his income derives from state contracts, mostly to build thousands of miles of roads and natural-gas pipelines and other infrastructure projects. Last year, the Russian edition of Forbes dubbed Rotenberg “the king of state orders” for winning nine billion dollars’ worth of government contracts in 2015 alone, more than any other Russian businessman. But perhaps the most salient detail in Rotenberg’s biography dates from childhood: in 1963, at the age of twelve, he joined the same judo club as Putin. The two became sparring partners and friends, and have remained close ever since.

Rotenberg’s success is a prime example of a political and economic restructuring that has taken place during Putin’s seventeen years in office: the de-fanging of one oligarchic class and the creation of another. In the nineties, a coterie of business figures built corporate empires that had little loyalty to the state. Under Putin, they were co-opted, marginalized, or strong-armed into obedience. The 2003 arrest, and subsequent conviction, of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the head of the Yukos oil company, brought home the point. At the same time, a new caste of oligarchs emerged, many with close personal ties to Putin. These oligarchs have been allowed to extract vast wealth from the state, often through lucrative government contracts, while understanding that their ultimate duty is to serve the President and shore up the system over which he rules.

The Crimean bridge is different from many of Rotenberg’s other state ventures, in that he is not expected to make much money from it. “This project is not about profits,” one banker in Moscow, who specializes in transportation and infrastructure, told me. He was matter-of-fact about how Rotenberg ended up in charge: “The bridge had to be built, and everyone else was refusing. It was the only possible solution.”

Construction began last year. Rotenberg, who has a reputation as an informed, hands-on manager, visits every few months, passing above the site in his helicopter before inspecting the project with a retinue of engineers and road-building specialists. Last fall, a correspondent from Russian state television filmed a fawning news segment about the bridge. Strolling with Rotenberg along one of the few completed sections, the host invoked the bridge’s reputation as “the construction project of the century.” The two put on hard hats and surveyed the jumble of cranes and excavators and drills in motion around them.

Rotenberg has the squat and powerful frame of a wrestler, and a round, impish face. His speech is clipped and straightforward, and he does not appear to enjoy introspection. But, when the television host pressed him to offer up platitudes on the bridge, Rotenberg did his best to oblige. “Besides financial profit—which, for a business, is a sign of success, of course—I also want the project to mean something for future generations,” he said. What Russians make of the bridge will be clear soon enough; the first cars will pass over it later this year. But its significance for Rotenberg already seems apparent. It is a totem of his service to the state and to its leader, Putin—and of their friendship, which has thrived at the intersection of state politics and big business.

Rotenberg was born in 1951 in Leningrad, a city deeply scarred by the Nazis’ two-and-a-half-year blockade during the Second World War. Rotenberg’s father, Roman, was a deputy director at the Red Dawn telephone factory, and his position gave the family a measure of stability and comfort. They lived in their own apartment, not a communal apartment like many families, including Putin’s. When Arkady was twelve, against his initial protests, his father took him to train with Anatoly Rakhlin, one of Leningrad’s better-known practitioners of sambo, a Soviet martial art that borrows from judo and was developed by Red Army officers in the nineteen-twenties. In a chaotic city, Rakhlin’s class offered teen-agers a redoubt of discipline. Putin, who was also in the class, said, in “ First Person ,” a book-length interview published during his first Presidential campaign, in 2000, that the training played a decisive role in his life. “Judo is not just a sport,” Putin said. “It’s a philosophy. It’s respect for your elders and for your opponent. It’s not for weaklings. . . . You come out onto the mat, you bow to one another, you follow ritual.”

Link copied

Rotenberg and Putin grew close travelling around Leningrad, and soon around the whole of the Soviet Union, for competitions. Nikolay Vaschilin, a retired K.G.B. officer who trained with them, remembers that the two were fond of pranks. (Putin later described himself during those years as “a troublemaker.”) One time, Vaschilin told me, the boys ran out of an alleyway during a May Day parade and threw wire pellets at balloons carried by the marchers, surprising them with a fusillade of pops. Another friend from that time recalled that he and Rotenberg would pilfer candy and other food from younger children at sports camps by sneaking up on them in the toilets, where kids would go to hide their treats from other boys: “They were immediately frightened and would give us a little something,” he said.

For fun, and a bit of spare cash, many of the young men in Rakhlin’s class worked as extras for a film studio in Leningrad, where they could earn ten rubles reënacting battle scenes in patriotic Soviet films about the Second World War. “Arkady showed himself to be a real brigadier,” Vaschilin recalled. “He was walking around and giving commands to everyone, even guys older than him. He was cocky, insolent, and mischievous—seventeen years old and already in charge.”

Putin had his eye on the K.G.B.—as he was later fond of recounting, he first volunteered his services when he was in ninth grade—but Rotenberg’s ambitions were in sports. He enrolled in the Lesgaft National State University of Physical Education, Sport, and Health, and graduated in 1978, after which he found work as a judo trainer. In 1990, Putin, after a K.G.B. posting in Dresden, took a job at the mayor’s office in Leningrad, which, a year later, after the Soviet collapse, was renamed St. Petersburg. Putin and Rotenberg, along with a handful of others from Rakhlin’s class, got together a few times a week to practice moves and stay in shape.

For Putin, who both by nature and by K.G.B. training is mistrustful of others, these early friendships seem to have been his only genuine, unguarded bonds. He would soon be surrounded by people who had something to offer, or something to ask. Rakhlin, who died in 2013, explained Putin’s affection for his former judo partners to the state-run newspaper Izvestia . “They are friends, and Putin’s character has maintained that healthy camaraderie,” Rakhlin said. “He doesn’t work with the St. Petersburg boys because they have pretty eyes, but because he trusts people who are proven.” In “First Person,” Putin said, “I have a lot of friends, but only a few people are really close to me. They have never gone away. They have never betrayed me, and I haven’t betrayed them, either. In my view, that’s what counts most.”

Trying to earn money in the nineteen-nineties, which were lean years in Russia, Rotenberg started a coöperative that organized sporting competitions with Vasily Shestakov, another boyhood friend from Rakhlin’s class. “We had worked in sports our whole lives,” Shestakov told me. “And then, all of a sudden, just like that: ‘perestroika,’ ‘business,’ all these unfamiliar words.” Neither had a talent for running a company. “Each of us thought the other one would do something,” Shestakov said. “And, as a result, no one did anything, and our coöperative fell apart.” Later that decade, Arkady’s younger brother, Boris, moved with his wife, Irina, to Finland. Before long, thanks to connections of Irina’s in the Russian gas industry, the brothers were trading in petroleum products. Irina and Boris separated in 2001, but she remains fond of the Rotenberg family. (She now goes by the name Irène Lamber.) “They have a natural intellect, a reasonable relation to everything, with a deep study of questions,” she told me. “All this was instilled in childhood.” Lamber suggested that business was not a true calling for them but an accident of fate. “Where would they be if the Soviet Union had never collapsed?” Lamber asked. “Arkady would be in charge of a state sports organization. He is a natural manager. And Boris would be a successful trainer.”

In the mid-nineties, Shestakov and a few others approached Putin, who was then the vice-mayor of St. Petersburg, with the idea of creating a professional judo club in the city. Putin gave his approval, and a number of wealthy businessmen—including the oil trader Gennady Timchenko, who knew Putin from city government—provided the funds. Rotenberg was named general director of the club, which was called Yavara-Neva. In the club’s second year, it came in second at the European Cup; the next year, in the German city of Abensberg, it won outright. On the judo mat, Rotenberg seized the championship trophy and gave it a kiss. “It left a good impression,” Shestakov told me. “I think that, of course, Putin was pleased.”

Since then, Yavara-Neva has won nine Euro Cups and produced four Olympic champions. Rotenberg remains the club’s general director. It is now building a new campus, which, in addition to a thousand-seat arena, will include a housing complex and a yacht club. Its cost is estimated at a hundred and eighty million dollars, paid for, in part, out of the St. Petersburg and federal budgets. When I met Alexey Zbruyev, the club’s athletic director, I asked whether Yavara-Neva might enjoy preferential treatment because of its connection to the President—for example, in financial donations from businessmen or in zoning approvals from bureaucrats. “We don’t brag about it anywhere,” Zbruyev said. “Everyone knows this perfectly well—why bring it up yet again? They know what Yavara-Neva is and who the club’s leaders are. Beyond that, no one asks any questions.”

In 2000, President Boris Yeltsin named Putin his successor, setting in motion a reorganization of the country’s political life. Putin believed that Russia had grown weak and ineffectual in the nineties, and during the first year of his Presidency he and a council of economic advisers carried out reforms meant to bolster the authority and the competency of the state. Some of those early reforms, such as the introduction of a flat tax, hewed to a pro-market, neoliberal framework. But one day Andrei Illarionov, a liberal-minded economist who was working closely with Putin, came across a Presidential order to create a state monopoly by combining more than a hundred liquor factories. No one had mentioned this new body, Rosspirtprom, at council meetings. Illarionov asked other Putin advisers if they knew about the plan, and none did.

“We had been discussing every issue related to the economy, so to come across a decree no one had heard of was quite a shock,” Illarionov told me. At best, Rosspirtprom would create another clunky bureaucracy at a time when Putin had promised to pursue the opposite course; at worst, Illarionov feared, it would be an opaque company that would allow for favoritism and corruption. “It was clear that there were other people, besides our economic council, from whom Putin was taking advice, and that he was making decisions for their benefit.”

Rotenberg and Putin were judo sparring partners

In the case of Rosspirtprom, that person was Rotenberg. He had suggested that Sergey Zivenko, with whom he had done business in the nineties, be put in charge of the company. When I met Zivenko, last fall, he called the creation of Rosspirtprom “a joint initiative” with Rotenberg—“a business project with a political tinge.” Rosspirtprom eventually controlled thirty per cent of the country’s vodka market, making it a key source of income for the state in the years before global oil prices skyrocketed. The company was an early test of Putin’s model of state capitalism, and, because it returned financial resources, and thus political power, to the Kremlin, Putin considered it a success.

Rotenberg also profited from the centralization, likely with Putin’s blessing. According to the logic of the Putin era, corruption is stealing without actually doing anything. Personal enrichment is seen as the proper reward for a completed project. “A lot of people tried to use their closeness with Putin to make a lot of promises they never carried out,” Zivenko said. “But not Rotenberg. He used this trust and delivered tangible accomplishments.” Rotenberg began using the success of Rosspirtprom “like his business card,” Zivenko said. Russian officials, and other businessmen, “saw that he was able to lobby his interests with the President, and must really be close to him, and so we have to be friends with him, too. Arkady was able to capitalize on—monetize, really—this image.”

In 2001, just before oil prices began a historic surge, Putin replaced the top executives of Gazprom, the major Russian gas company, with close associates, effectively bringing the company under the Kremlin’s direct control. Mikhail Krutikhin, a partner at RusEnergy, a consultancy in Moscow, told me that Gazprom began functioning as “the personal company of the President—all decisions regarding Gazprom, whether launching big investment projects or naming top corporate officials, were made by the President’s office.” Around this time, Arkady and his brother, Boris, began investing in companies that serviced Gazprom. They founded SMP Bank in 2001, and used it to acquire stakes in construction, gas, and pipe companies; by the mid-aughts, the brothers had become one of Russia’s main suppliers of large-diameter gas pipes.

At nearly every turn, Gazprom spent more than seemed necessary or appropriate—and, in many cases, the Rotenberg brothers stood to benefit. To take just one example, in 2007, when Gazprom needed to deliver gas from a new field above the Arctic Circle, it decided against a plan, which had been circulating for years, that called for building a short link to an existing network three hundred and fifty miles away. Instead, it built a brand-new pipeline fifteen hundred miles to the south, with a final price tag of forty-four billion dollars—three times what a pipeline of that length usually costs. “The only explanation was that this was a chance for contractors to make a lot of money,” Krutikhin said.

When Gazprom built pipelines inside Russia during the next decade, they were two to three times more expensive than equivalent projects in Europe, even when they were in temperate, accessible areas in southern Russia. Perhaps the most striking example of inefficiency occurred in 2013, when Gazprom announced that the cost of a pipeline that Rotenberg was building in Krasnodar—a warm, flat region near the Black Sea—had risen by forty-five per cent. No explanation was given; wages were relatively stable, as was the price of steel. That stretch of pipeline was meant to feed into a larger pipeline going through Bulgaria. After the Russian government suspended construction on the Bulgarian pipeline, Rotenberg’s project miraculously went on for another year. Mikhail Korchemkin, the head of East European Gas Analysis, said that it became clear that Gazprom had “switched from a principle of maximizing shareholder profits to one of maximizing contractor profits.” The company’s projects, he said, presented a “way of minting new billionaires in Russia: overpay for services and make them rich.”

Rotenberg’s greatest business achievement came in 2008, when Gazprom sold him five construction and maintenance companies, for which he paid three hundred and forty-eight million dollars. He merged the firms into a single company, Stroigazmontazh (or S.G.M.), which immediately became one of the chief contractors for Gazprom. In the company’s first year of operations, it earned more than two billion dollars in revenue, an amount that suggested that the sale price was many times lower than market value. A short time later, the Rotenberg brothers bought a brokerage firm called Northern European Pipe Project. The normal profit margin for such companies is around ten to fifteen per cent, but several people with knowledge of the industry said that, during the boom years, N.E.P.P. earned as much as thirty per cent. At the height of its operations, it supplied ninety per cent of all large-diameter pipes purchased by Gazprom.

Before the Crimean bridge, no construction project was as personally important to Putin as the preparations for the 2014 Winter Olympics , in Sochi. The city of Sochi, which is on the far-western edge of Russia, overlooking the Black Sea, was developed as a resort area under the tsars, and later became a favorite retreat of Soviet workers, but it had little in terms of modern athletic infrastructure. Nearly everything, from ski resorts to the mountain roads leading up to them, had to be built from scratch, and before long the 2014 Games had become the most expensive in history, with an estimated budget of fifty-one billion dollars. One company controlled by Rotenberg built a nearly two-billion-dollar highway along the coast. Another built an underwater gas pipeline leading to Sochi at a price well over three times the European average. In all, companies controlled by Rotenberg received contracts worth seven billion dollars —equivalent to the entire cost of the previous Winter Olympics, in Vancouver, in 2010.

It is impossible to identify the line between where the Rotenberg brothers have, thanks to their name and connections, pocketed outsized profits from state contracts and where they’ve merely had a knack for finding opportunities to make money. When I asked Irène Lamber, Boris’s ex-wife, whether Putin actively assisted the Rotenberg brothers, she told me that she wouldn’t rule it out. “They were friendly in childhood, and those relationships were never broken, so logically you can presume some sort of advice was given, at a minimum, and perhaps help here and there,” she said. As Konstantin Simonov, the director of the National Energy Fund, put it to me, “The story is simple: with a company like Gazprom, not just anybody can show up off the street and say, ‘I want to build a giant gas pipe.’ It’s clear that Rotenberg needed a serious degree of political support on the first step.” But personal favors alone didn’t make Rotenberg successful. “Rotenberg proved himself to be a very tenacious guy, with real organizational skills and a willingness to take risks,” Simonov said.

When I spoke with Bogdan Budzulyak, a former Gazprom board member, he was full of praise for the Rotenbergs, and told me that the ties between the brothers and Putin “were not raised or spoken about. But we understood, it goes without saying, that they had earned the trust they were given.” Rotenberg has directly addressed the friendship in a few interviews. “I would never go to the President and ask him for something,” he told one reporter. “That would mean depriving myself of the pleasure I get from our conversations.” In the Russian edition of Forbes , he acknowledged that “knowing someone at that level has never hurt anyone,” but argued that the bond only makes things harder for him. “Unlike a lot of other people, I don’t have the right to make a mistake,” he said. “Because it’s not a question of just my reputation.”

In the nineties, Russia’s oligarchs appropriated state assets—industrial production, mining, and oil and gas deposits—and did what they wanted with them. The oligarchs of the Putin era, on the other hand, are themselves assets of the state, administering business fiefdoms that also happen to pay handsomely. Many have a long-standing relationship with the President, and a particular sphere of responsibility. Rotenberg’s is infrastructure. Gennady Timchenko, one of the initial supporters of Yavara-Neva, came to preside over the oil trade; at one point, a firm he controlled sold as much as thirty per cent of the country’s oil exports. Yury Kovalchuk is the Kremlin’s unofficial cashier and media minister; the U.S. Treasury Department called him “the personal banker for senior officials of the Russian Federation, including Putin.” Bank Rossiya, which he chairs, is worth ten billion dollars, and Kovalchuk’s personal wealth is estimated at one billion dollars.

“If oligarchy 1.0 tried to grab pieces of the economy from the state, and use them for themselves, then oligarchy 2.0 tries to build themselves into the state system, in order to gain access to state contracts and budget money,” Ekaterina Schulmann, a political scientist and noted analyst of the Russian political system, explained. As Clifford Gaddy, an economist who studies Putin’s economic strategy, put it, “His vision of the country’s entire economy is ‘Russia, Inc.,’ where he personally works as the executive director” and the owners of nominally private firms are “mere divisional managers, operational managers of the big, real corporation.”

A source close to the Kremlin insisted that the rise of Rotenberg and similar Putin-era nouveau oligarchs was not the result of a purposeful plan: “It wasn’t Putin’s strategy to create these people. That’s a fantasy. He may have agreed to help them, and at a certain point, once they became large and successful, he realized that they might be useful, that it’s not so bad to have a caste of very wealthy people who are obligated to you.” In effect, Putin’s oligarchs form a shadow cabinet. Evgeny Minchenko, a political scientist in Moscow, told me, “These are trusted people, who will stick with Putin until the end, to whom he can assign certain tasks, who won’t get frightened by external pressure.” They can take on projects the Kremlin doesn’t want to fund or manage, such as sports teams, media programs, and political initiatives.

A well-connected banker told me that many oligarchs finance the “black ledger,” which, as the banker explained, is “money that does not go through the budget but is needed by the state, to finance elections and support local political figures, for example.” Funds leave the state budget as procurement orders, and come back as off-the-books cash, to be spent however the Kremlin sees fit. The Panama Papers, leaked last April, revealed that, between 2007 and 2013, nearly two billion dollars had been funnelled through offshore accounts linked to Putin associates. In 2013, companies affiliated with Rotenberg sent two hundred and thirty-one million dollars in loans, with no repayment schedule, to a company based in the British Virgin Islands. What happened to that money is a mystery. A spokesperson for Rotenberg said it was transferred for “specific transactions under commercial terms,” without clarifying the nature of the deal. Separately, tens of millions of dollars passed through offshore companies registered to Sergey Roldugin, a cellist who befriended Putin in the seventies and who is the godfather of Putin’s eldest daughter, Maria. Addressing the transactions last April, Putin said of Roldugin: “He spent almost all the money he earned acquiring musical instruments from abroad and bringing them to Russia.” (Roldugin has denied any wrongdoing.) Putin’s thinking seems to be that there is no need to own anything himself, at least on paper, when trusted allies can do it for him.

Putin’s Russia has been given many labels, from kleptocracy to Mafia state, but the most analytically helpful may be among the oldest: feudalism. “It is not a metaphor but a very exact definition of the system,” Andrey Movchan, a banker and finance expert in Moscow, said. If in the Middle Ages the chief feudal currency was land, in today’s Russia it is hydrocarbon wealth. Movchan explained how, in the Middle Ages, feudal lords were often “one handshake away from the king: their post, and the size of the resource, was decided by the king alone.” The land ultimately belonged to the king, and was awarded to feudal lords on a provisional basis. The same is true in Russia today, he said.

The system that Putin has established suggests a degree of weakness, insecurity, and even fear. Putin has little faith in the effectiveness of his rule, which is why true responsibility in his state is shared by only a handful of intimately connected people. Schulmann told me that in Russia’s political system “there are no such things as qualifications, talent, skill, experience. None of that is important.” What is important, she said, parroting Putin, “is that I’m not afraid. And the only way I won’t be afraid is if I see a familiar face next to me.” She continued, “How can I protect myself? I grab my friend Arkady, one of the few people I can trust.”

In November, 2013, a wave of protests swept through the Ukrainian capital, Kiev. Initially sparked by President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign a trade deal with the European Union, they quickly grew to include objections to the corruption of Yanukovych’s administration and its violent response to the demonstrations. The movement reached a chaotic end in February, 2014, when Yanukovych fled the capital in the middle of the night. Putin, fearing that Ukraine was turning toward Europe, secretly ordered Russian forces to enter the Crimean Peninsula. Crimea had been a part of the Russian Empire from the eighteenth century until 1954, when Nikita Khrushchev gave it to Soviet Ukraine as a gesture of friendship. Much of the Crimean population still had great affection for and close cultural ties to Russia, which many locals call their “big brother.” It wasn’t difficult for Putin to whip up a pro-Moscow campaign, fuelled by propaganda and backed by Russian special forces. In a stage-managed referendum, ninety-seven per cent of Crimeans voted to join Russia. Russian-backed separatists were soon battling the Ukrainian military in Eastern Ukraine; at several key points, Russian forces intervened to shift the momentum in the fighting.

In March, 2014, the Obama Administration imposed sanctions on Russia for its interference in Ukraine; it included Arkady and Boris Rotenberg on its list of sanctioned individuals. The Treasury Department identified the brothers as “members of the Russian leadership’s inner circle,” who “provided support to Putin’s pet projects by receiving and executing high-price contracts for the Sochi Olympic Games and state-controlled Gazprom.” (Arkady, but not Boris, was added to the E.U.’s sanctions list that July.) It is unclear what role, if any, Arkady played in the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy, but that wasn’t the point. “We wanted to make clear to the inner circle that Putin can’t protect them, that he can’t shield his cronies,” Daniel Fried, who was in charge of the sanctions policy in the State Department during the Obama Administration, told me. The theory was that sanctions would make the lives of rich and powerful individuals close to Putin more difficult, and certainly less profitable, and that their material suffering might deter further aggression.

Rotenberg did experience some inconveniences. Visa and MasterCard stopped servicing cards issued by SMP Bank, but the bank is as much a hub for Rotenberg’s personal businesses as it is a commercial project. In September, 2014, Italian authorities seized a number of Rotenberg’s properties in Italy: among them, three villas on the island of Sardinia, one in the city of Tarquinia, and a luxury hotel in Rome. The newspaper Corriere della Sera estimated the combined value of the real estate at thirty million euros. Rotenberg admitted that the sanctions have forced some adjustments in his life: “Before, I used to wonder whether I should go to France or Italy—I loved to vacation in Italy—but now there is no such question. There are plenty of beautiful places in Russia.” After Rotenberg’s properties in Italy were taken, Russia’s parliament considered what came to be known as “the Rotenberg law,” which proposed that the state compensate Russian citizens for assets seized by foreign governments. (The bill was never passed; Rotenberg said that he had nothing to do with it.)

Contrary to the Obama Administration’s hopes, however, Rotenberg drew even closer to Putin. So did Timchenko and Kovalchuk, who were also on the sanctions list. Their response was partly about personal loyalty. “I have great respect for Putin and I consider him sent to our country from God,” Rotenberg told the Financial Times . But it also made rational sense: the Russian state is Rotenberg’s main client and source of wealth, so it would be far costlier to turn against Putin than to bear the burden of sanctions.

In fact, Western sanctions may have been a boon for Rotenberg, giving him a chance to show Putin that he had suffered for the country and was owed some payback. “It’s now quite obvious that whoever ended up under sanctions found himself in a more privileged position,” Minchenko, the political scientist, said. In a roundabout way, he told me, the United States and the E.U. “made a contribution to the increased influence of these people.” Indeed, after the sanctions, Rotenberg’s state orders grew: in 2015, he received nine billion dollars in government contracts, compared with three and a half billion dollars the year before.

In November, 2015, Russia began charging long-distance truck drivers a per-kilometre toll for travelling on federal roads. One of the co-owners of the company awarded the contract for the toll system was Igor Rotenberg, Arkady’s forty-two-year-old son, who has taken over major shares in several businesses once held by his father. Documents later showed that Igor’s company, which had no competition for the contract, would be paid a hundred and fifty million dollars each year until 2027, according to the exchange rate at the time. In a rare flash of unrest, hundreds of truck drivers protested the measure, blocking highways leading into Moscow and posting signs in their windshields that read “Russia Without Rotenberg” and “Rotenberg Is Worse Than ISIS .” When, this spring, the toll was further increased, demonstrations erupted again, especially in the North Caucasus, where drivers formed protest encampments.

Any enterprise to which Rotenberg lends his name now seems to succeed. In 2014, as the Times reported , after Rotenberg became the chairman of a Russian textbook publisher, Enlightenment, the Ministry of Education and Science eliminated more than half the titles in the country’s schools, often for flimsy technical reasons. Enlightenment, whose books were largely untouched, was left with an outsized share of a market worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year. This past winter, the Moscow city government decorated the center of town for the New Year; as an investigation by the independent Russian news site Meduza found, a company affiliated with the Rotenberg brothers was awarded a contract to install the decorations. According to Meduza, the company charged the city nearly five times the actual cost for dozens of illuminated garlands in the shape of champagne flutes: about thirty-seven thousand dollars instead of eight thousand dollars for each light fixture. (A spokesperson for Rotenberg denied any affiliation with the firm.)

Ilya Shumanov, the deputy director of the Moscow office of Transparency International, said that, although many of these deals seem suspect, it would be difficult to catch Rotenberg “red-handed breaking the law,” not only because of his robust legal staff, but because the various arms of the Russian state, from parliament to government auditors, work together to create a “legal window” for his business. For example, although Russian law requires that state procurement contracts be awarded through open bidding, it also allows them to be granted in a closed, no-bid process if the projects are deemed strategically important—a category that the state itself determines, and doesn’t have to explain or justify. A 2015 report prepared for the Russian government showed that ninety-five per cent of state purchases were uncompetitive, and forty per cent were made with a single supplier. Many of Rotenberg’s largest and most lucrative orders have been awarded without open bidding. One gas-industry expert told me that in some cases fake companies were even set up to pose as bidders. As Shumanov put it, “You could call it an imitation of legality. The letter of the law is observed, even if it is broken in spirit.”

The idea of building a bridge to Crimea was first raised by a British imperial consortium in the late nineteenth century, when engineers briefly considered a rail line that would run from London to New Delhi, via the peninsula. In the nineteen-thirties, under Stalin, Soviet railway planners revived the proposal as part of the country’s industrialization drive, but the project went nowhere. During the Nazi campaign to seize the Caucasus, in 1942, German soldiers took the first steps to construct a bridge. Before they could complete the project, Soviet soldiers captured the area. Within a few months, Red Army engineers had built a one-track rail bridge, but in February, 1945, four months after the first freight train passed over it, an ice floe hit the bridge and it collapsed.

Soviet officials returned to the idea of a bridge from time to time in the following decades, but the proposals were always rejected as too expensive. The Kerch Strait is a challenging place to build, with complicated geology, high seismic activity, and stormy weather. The seafloor is covered in a layer of crumbly silt that reaches as deep as two hundred feet. Freshwater from the Don River flows into the sea, which means that the surface often freezes in winter; high winds create cracks in the ice, and as the ice floes break apart they put pressure on anything standing in the water.

Oleg Skvortsov, an engineer with a long career overseeing bridge construction, was the chairman of the council of experts that advised the Russian government on the Crimea project. He said that, in the nineties, when it was a kind of fantasy, he opposed the idea of a bridge. “But the situation changed,” he said, with Ukraine’s blockade. Crimea has to find a way to transport its fish, wine, fruit, and other goods to Russia. “I love Crimean peaches, for example,” he said. “You can only find such peaches in Italy.” Skvortsov told me that he “wouldn’t consider Rotenberg a builder,” and then began to talk about his father, an engineer who worked under Feliks Dzerzhinsky, the chief commissar for railway construction in the twenties—and also a notorious and feared Bolshevik and the founding head of the Soviet secret police, which later became the K.G.B. “He rebuilt all the rail lines in a ruined country,” Skvortsov said of Dzerzhinsky. “My father said he was a brilliant supervisor, largely because he never got too involved in technical details. I think Rotenberg is the same way.”

Like most economic activity connected to Crimea, the bridge is a target of U.S. sanctions. Fried, the former State Department official, told me, “We never thought we could prevent the bridge, but we could try and make it massively costly and radioactive, so that Crimea never pays for itself, that it turns out not to be a war prize but a liability.” The sanctions do not seem to have affected construction or greatly raised costs, but they have created a few complications. It initially proved impossible to find an established insurance company to underwrite the project, and so an obscure insurance company in Crimea took on more than three billion dollars in potential risk.

As Russia began to slide into recession, the bridge started to look more and more like an extravagance. In the past several years, the Kremlin has cut budget expenditures in nearly every category. In February, an official with Russia’s roadways agency let slip, perhaps accidentally, how many resources the bridge was using. “On account of this bridge, the building of new automobile roads in Russia has been practically suspended,” he said. “The country does not have enough money. Therefore, we cannot implement everything we want.”

Still, if the Kremlin considers a project a priority, it can successfully mobilize the country’s resources. Mikhail Blinkin, the director of the transportation institute at the Higher School of Economics, in Moscow, told me that big infrastructure projects in Russia are often held up by piecemeal financing and bureaucratic roadblocks. “But in the Kerch case,” Blinkin said, “the funding was sufficient, and all the usual obstacles were eliminated on the political level.” It now appears likely that the bridge will be fully operational, to train and car traffic, a year ahead of schedule—in time for the next Presidential election, Putin’s fourth. In an attempt to boost turnout by appealing to patriotic sentiment, the vote may be held on the anniversary of Crimea’s annexation.

Blinkin told me that the bridge wasn’t strictly necessary; Crimea could accommodate travellers to and from the peninsula by simply increasing the number of ferries between the city of Kerch and the Russian mainland. He noted that far more passengers travel between Helsinki and Stockholm, for example, exclusively by ferry. But an expansion in ferry service is not as grand as a bridge, and doesn’t send a message about Russia’s status as a world power. “Is that worth such gigantic expense?” Blinkin asked. “In a strict economic sense, no. But, if you factor in the political component, then yes.”

I visited the bridge in January. It is being built not in a line, from one end to the other, but in eight separate parts at once, and for the moment it resembles a concrete-and-steel archipelago rising from the sea. On the mainland side, construction is centered in the town of Taman, which was settled by Cossacks in the eighteenth century, and which Mikhail Lermontov, in his novel “ A Hero of Our Time ,” called “the nastiest little hole of all the seaports of Russia.” When I arrived in Taman, the streets, quiet save for a few construction workers, were covered in a dusting of snow, and a freezing wind snapped through town.

At the bridge site, teams of workers watched over drills the size of redwood trees, which rammed steel piles into the seafloor. The scale of construction was almost too immense to comprehend. As the foundation of the bridge curved toward Crimea, it disappeared on the horizon. In a trailer, I sat down with Leonid Ryzhenkin, an official from Rotenberg’s construction company who is in charge of the site and its five thousand workers. Ryzhenkin’s wife’s family is from Sevastopol, a storied naval port in Crimea, and in the tense days before the referendum, one of his in-laws joined a pro-Russian militia. He told me about spending five hours taking a ferry and then a taxi to visit his in-laws. “My elderly mother-in-law calls all the time and asks, ‘So, Lenya, how’s it going? When are we going to drive across the bridge?’ ” he said. “And I tell her not to worry, we’ll make it in time.” He told me that Crimea is home to “native Russian people,” and that the bridge will “allow us all to be reunited.”

Roman Novikov, an official from Russia’s state road agency, joined us, and when I asked his assessment of Rotenberg he was eager to respond with praise. “I have the sense that he is deeply immersed in the project,” Novikov said. He offered an explanation for Rotenberg’s interest. “It’s no secret that he talks with his childhood friend, from when they were young, who is also interested, of course, in this object,” he said. Just in case there was any confusion, Novikov clarified: “I am speaking of the President of the Russian Federation.” ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mark Lawrence Schrad

By Ed Caesar

By Amanda Petrusich

By David Remnick

This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

Naval Point Club Lyttelton seeks Programmes Manager

Interesting and varied role

Attention to detail a must

Fun working environment

Full time position

The Organisation:

The Naval Point Club Lyttelton is a successful, award winning and innovative water sports club. Our passion lies in giving our members and other users of our facilities a high-quality experience as they participate in their chosen sea-based activities. Our membership includes a growing and diverse range of users and age groups. The club facilities also play an important part in the life of the Lyttelton Community.

The Naval Point Club Lyttelton is looking for an organised and proactive programmes manager who thrives in a busy and friendly environment. This is a key role with specific responsibilities for:

- Development, administration, promotion and delivery of programmes for junior, youth and adult participants aligned to Naval Point Clubs user groups.

- Building both internal and external participation in all our programmes

- Development and coordination of instructors and coaches to assist with and ensure the programmes run efficiently and meet user expectations.

- Development of pathways that encourage programme participant's transition into regular participation in their chosen activity.

- Maintain knowledge of key changes and innovations to relevant programs.

Your key strengths will allow you to quickly develop and plan the implementation of programmes and activities that promote and support our core user groups, dinghy, keel boat, windsurf, Waka-Ama, trailer yacht, power boat and other open water sports. While also meeting the organisation's strategic objectives.

You will be an excellent communicator who can work with and interact with, a wide range of stakeholders (internal and external), groups and personalities, all of whom are important. Your current or past experience will highlight your ability in developing, programming and managing significant on-water (e.g. sailing, etc.) and other events. Your previous experience will also highlight your strong administration and organisational skills, particularly with budgeting and volunteer resourcing.

This is an exciting opportunity for a person who is looking for a challenging yet rewarding role. That will allow them to bring all their skills and experience to bear in assisting the Naval Point Club Lyttelton to deliver world-class programmes and experiences for its members and other external user groups. The role is full time, Saturday and Sunday work will be required.

To be successful in the role you will have experience in similar environments where good communication, prioritisation and multi-tasking skills, combined with an attention to detail are essential. You will demonstrate an ability to develop, implement and manage interesting and innovative participation programmes. You will have a genuine desire to help our members and visitors have a great experience. You will also have a sense of humour, be quick on the uptake and recognise opportunities where you can make a change and help the team by getting things done.

If you would love to work in a friendly, fast-paced and dynamic club, then apply now!

Please apply on-line at SEEK, click the APPLY button and submit your CV .

Alternatively, for confidential enquiries about this job, please contact: [email protected] or [email protected]

Related news

Sailing 'mecca' beckons as NZ youth champions crowned

'Pretty significant moment': Team New Zealand reveal new AC 75 for America's Cup

In pictures: 2024 Corporate Sailing Day

E-newsletter sign up.

- Skip Navigation

- Food Pantry Items

Most Beautiful Metro Stations in Moscow

Visiting Moscow? Get yourself a metro card and explore Moscow’s beautiful metro stations. Moscow’s world-famous metro system is efficient and a great way to get from A to B. But there is more to it; Soviet mosaic decorations, exuberant halls with chandeliers, colourful paintings and immense statues. Moscow’s metro is an attraction itself, so take half a day and dive into Moscow’s underground!

The best thing to do is to get on the brown circle (number 5) line since the most beautiful metro stations are situated on this line. The only exception is the metro stop Mayakovskaya one the green line (number 2). My suggestion is to get a map, mark these metro stops on there and hop on the metro. It helps to get an English > Russian map to better understand the names of the stops. At some of the metro stops, the microphone voice speaks Russian and English so it’s not difficult at all.

Another thing we found out, is that it’s worth taking the escalator and explore the other corridors to discover how beautiful the full station is.

Quick hotel suggestion for Moscow is the amazing Brick Design Hotel .

These are my favourite metro stations in Moscow, in order of my personal preference:

1. Mayakovskaya Station

The metro station of Mayakovskaya looks like a ballroom! Wide arches, huge domes with lamps and mosaic works make your exit of the metro overwhelming. Look up and you will see the many colourful mosaics with typical Soviet pictures. Mayakovskaya is my personal favourite and is the only stop not on the brown line but on the green line.

2. Komsomolskaya Station

Komsomolskaya metro station is famous for its yellow ceiling. An average museum is nothing compared to this stop. Splendour all over the place, black and gold, mosaic – again – and enormous chandeliers that made my lamp at home look like a toy.

3. Novoslobodskaya Station

The pillars in the main hall of Novoslobodskaya metro station have the most colourful stained glass decorations. The golden arches and the golden mosaic with a naked lady holding a baby in front of the Soviet hammer and sickle, make the drama complete.

4. Prospect Mira Station

The beautiful chandeliers and the lines in the ceiling, make Prospekt Mira an architectural masterpiece.

5. Belorusskaya Station

Prestigious arches, octagonal shapes of Socialistic Soviet Republic mosaics. The eyecatcher of Belorusskaya metro station, however, is the enormous statue of three men with long coats, holding guns and a flag.

6. Kiyevskaya Station

The metro station of Kiyevskaya is a bit more romantic than Belorusskaya and Prospect Mira. Beautiful paintings with classical decorations.

7. Taganskaya Station

At the main hall Taganskaya metro station you will find triangle light blue and white decorations that are an ode to various Russians that – I assume – are important for Russian history and victory. There is no need to explore others halls of Taganskaya, this is it.

8. Paveletskaya Station

Another and most definitely the less beautiful outrageous huge golden mosaic covers one of the walls of Paveletskaya. I would recommend taking the escalator to the exit upstairs to admire the turquoise dome and a painting of the St Basil’s Cathedral in a wooden frame.

Travelling with Moscow’s metro is inexpensive. You can have a lot of joy for just a few Rubbles.

- 1 single journey: RMB 50 – € 0,70

- 1 day ticket: RMB 210 – € 2,95

Like to know about Moscow, travelling in Russia or the Transsiberian Train journey ? Read my other articles about Russia .

- 161 Shares

You may also like

Hunting for the best coffee in irkutsk, amsterdam forest: a day trip for nature..., a romantic amalfi coast road trip itinerary, complete weekend city guide to maastricht, olkhon island: siberian sunsets over lake baikal, 8 great reasons to visit mongolia in..., trans-siberian railway travel guide, all you need to know for your..., food & drinks in moscow, why we love grünerløkka in oslo.

Wow! It is beautiful. I am still dreaming of Moscow one day.

It’s absolutely beautiful! Moscow is a great city trip destination and really surprised me in many ways.

My partner and I did a self guided Moscow Metro tour when we were there 2 years ago. So many breathtaking platforms…I highly recommend it! Most of my favorites were along the Brown 5 line, as well. I also loved Mayakovskaya, Arbatskaya, Aleksandrovski Sad and Ploshchad Revolyutsii. We’re heading back in a few weeks and plan to do Metro Tour-Part 2. We hope to see the #5 stations we missed before, as well as explore some of the Dark Blue #3 (Park Pobedy and Slavyansky Bul’var, for sure), Yellow #8 and Olive #10 platforms.

That’s exciting Julia! Curious to see your Metro Tour-Part 2 experience and the stations you discovered.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Related Guides:

Moscow Neighbourhoods, Locations and Districts

(moscow, central federal district, russia), city centre, tverskoy district, arbat district, barrikadnaya. district, khamovniki district, chistye prudy district, zamoskvorechie district, zayauzie district.

© Copyright TravelSmart Ltd

I'm looking for:

Hotel Search

- Travel Guide

- Information and Tourism

- Maps and Orientation

- Transport and Car Rental

- SVO Airport Information

- History Facts

- Weather and Climate

- Life and Travel Tips

- Accommodation

- Hotels and Accommodation

- Property and Real Estate

- Popular Attractions

- Tourist Attractions

- Landmarks and Monuments

- Art Galleries

- Attractions Nearby

- Parks and Gardens

- Golf Courses

- Things to Do

- Events and Festivals

- Restaurants and Dining

- Your Reviews of Moscow

- Russia World Guide

- Guide Disclaimer

- Privacy Policy / Disclaimer

COMMENTS

Welcome to The Naval Point Club Lyttelton Incorporated (NPCL). The Club was established in 2001 following the amalgamation of the Banks Peninsula Cruising Club est. 1932; and the Canterbury Yacht and Motor Boat Club est. 1921. With over 700 members the Club, based at Magazine Bay in Lyttelton, provides opportunities for boats of all classes ...

Naval Point Club Lyttelton, Lyttelton, New Zealand. 2,068 likes · 40 talking about this · 1,501 were here. Based in Lyttelton, Naval Point Club caters for keelers, trailer yachts,motor boats,...

Welcome to Naval Point Club Lyttelton. The Club was established in 2001 following the amalgamation of the Banks Peninsula Cruising Club est. 1932; and the Canterbury Yacht and Motor Boat Club est. 1921. With over 750 members the Club, based at Magazine Bay in Lyttelton, provides opportunities for boats of all classes, including junior/youth ...

With over 750 members the Club, based at Magazine Bay in Lyttelton, the Naval Point Yacht Club provides opportunities for boats of all classes, including junior/youth dinghies, senior dinghies, windsurf, trailer yachts, keelboats, powerboats, waka, jet-ski, swim and other open water sports. Naval Point welcomes anyone interested in open water ...

Naval Point club Lyttelton offers a wide range of on water activities for all age groups. We have a particular focus on youth learn to sail, in a variety of vessels. Naval Point Club Lyttelton | Yachting New Zealand

25 Aug 2021. The Naval Point Club Lyttelton will in November celebrate 100 years of sailing in Lyttelton and many of the major events and personalities over this time have been captured in a special book. Sailing in a Volcano records the history of three phases of the Naval Point Club Lyttelton (NPCL) from its roots in the Canterbury Yacht Club ...

Welcome to The Naval Point Club Lyttelton Incorporated (NPCL). The Club was established in 2001 following the amalgamation of the Banks Peninsula Cruising Club est. 1932; and the Canterbury Yacht and Motor Boat Club est. 1921. With over 700 members the Club, based at Magazine Bay in Lyttelton, provides opportunities for boats of all classes, […]

The Club was established in 2001 following the amalgamation of the Banks Peninsula Cruising Club est. 1932; and the Canterbury Yacht and Motor Boat Club est. 1921. Naval Point Club has excellent facilities, is an all-tide venue and offers many services to its members. A comprehensive member's handb

Naval Point welcomes anyone interested in open water sports. Venue available for hire. Phone. 328-7029. Email. [email protected]. Location. 46 Norwich Quay, Lyttelton 8082. Postal Address. PO Box 19733, Woolston, Christchurch 8241. Programmes / Events. Learn to sail for children through to adults, and Junior Learn to Windsurf also available.

Cholmondeley Charity Yacht Race It's that time of year again where we are on the hunt for a number of boats to help us support Cholmondeley Children's Centre for their annual charity race day. Last year we had 17 boats on the water from our biggest keelboats right down to trailer yachts.

The Naval Point Club Lyttelton page on YachtsandYachting.com - the first place to stop for reports, results, fixtures & photographs from racing sailing

Some of that development will be done in time for March's New Zealand Sail Grand Prix in Lyttelton. The hub already has a membership in excess of 2500 members even though it has been in existence for about only two months. About 750 of those members of the Naval Point Club Lyttelton, which is the largest sailing club in the Canterbury region.

Naval Point Club Lyttelton | 31 followers on LinkedIn. Christchurch's premier water sports club. Offering sailing, waka, ocean swimming, kayaking, stand up paddleboarding, power boating ...

Established in 2001, the Naval Point Club is the result of uniting the Banks Peninsula Cruising Club and the Canterbury Yacht and Motor Boat Club. We have over 1000 members and we are based at Magazine Bay, Lyttelton. Naval Point Club has excellent facilities, is an all-tide venue and offers many services to its members.

207 Followers, 36 Following, 53 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from Naval Point Club Lyttelton (@navalpointclublyttelton) navalpointclublyttelton. Follow. Message. 53 posts; 211 followers; 36 following; Naval Point Club Lyttelton. Stadium, Arena & Sports Venue. We are Christchurch's largest all-tide sailing venue. ...

By Joshua Yaffa. May 22, 2017. The Crimean bridge, which is being built by Arkady Rotenberg, spans twelve miles and will cost billions of dollars. Putin sees the project as a key marker of Russia ...

The Naval Point Club Lyttelton is looking for an organised and proactive programmes manager who thrives in a busy and friendly environment. This is a key role with specific responsibilities for: Development, administration, promotion and delivery of programmes for junior, youth and adult participants aligned to Naval Point Clubs user groups.

Food Pantry Hours. Thursdays from 9:00am - 11:30am. Closed - Every FIFTH Thursday of any given month AND Holidays that fall on a Thursday. For more information contact: 636-356-4266.

4. Prospect Mira Station. The beautiful chandeliers and the lines in the ceiling, make Prospekt Mira an architectural masterpiece. 5. Belorusskaya Station. Prestigious arches, octagonal shapes of Socialistic Soviet Republic mosaics. The eyecatcher of Belorusskaya metro station, however, is the enormous statue of three men with long coats ...

Arbat District. The district known as Arbat is bordered on both of its sides by the Moscow River and includes the neighbourhoods located directly south of the Nova Arbat Ulitsa and also those on the northerly side of the Garden Ring. The Ulitsa Arbat is a definite highlight and this pedestrian mall stretches for just over 1 km / 0.5 miles ...